The question of whether a political party qualifies as a social group is a nuanced and thought-provoking issue that intersects sociology, political science, and philosophy. At its core, a political party is an organized collective with shared ideological goals, often focused on influencing governance and policy-making. However, its classification as a social group depends on how one defines social group, which traditionally refers to a collective united by common interests, identities, or interactions beyond formal structures. While political parties foster camaraderie and shared purpose among members, their primary function is instrumental—advancing specific agendas—rather than purely social or relational. Thus, while they exhibit social group characteristics, their purpose-driven nature may distinguish them from more organically formed social collectives, leaving the question open to interpretation and debate.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Shared Interests and Goals | Political parties are formed around shared ideological, policy, or societal goals, which aligns with the definition of a social group as having common interests. |

| Collective Identity | Members of a political party often identify with the party's ideology, values, and mission, fostering a sense of collective identity, a key trait of social groups. |

| Social Interaction | Party members interact through meetings, campaigns, and events, creating social bonds and networks, similar to other social groups. |

| Organizational Structure | Political parties have formal structures (e.g., leadership, committees), which distinguish them from informal social groups but still qualify as organized social entities. |

| Influence on Society | Parties aim to influence policy and governance, reflecting their role as a social group with collective agency and impact on broader society. |

| Membership Criteria | While parties may have formal membership requirements, social groups often have implicit or explicit criteria for inclusion, making this a shared characteristic. |

| Conflict and Competition | Political parties often compete with one another, which is analogous to intergroup dynamics in social psychology, further supporting their classification as social groups. |

| Cultural and Symbolic Elements | Parties use symbols, slogans, and rituals (e.g., rallies) to reinforce group identity, similar to cultural practices in other social groups. |

| Dynamic Membership | Membership in political parties can change over time, reflecting the fluid nature of social group participation. |

| External Recognition | Political parties are recognized as distinct social entities by society, institutions, and media, solidifying their status as social groups. |

Explore related products

$11.99 $16.95

What You'll Learn

- Definition of Social Groups: Criteria for classifying political parties as social groups based on shared goals

- Membership Dynamics: How party membership fosters social cohesion and collective identity among individuals

- Social Interaction: Role of party activities in creating social bonds and networks among members

- Cultural Influence: Impact of political parties on shaping societal norms, values, and cultural practices

- Exclusion vs. Inclusion: How parties can act as both inclusive communities and exclusive social groups

Definition of Social Groups: Criteria for classifying political parties as social groups based on shared goals

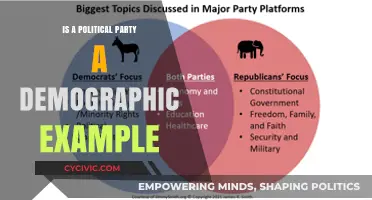

Political parties are often viewed as vehicles for power, but their classification as social groups hinges on a deeper analysis of shared goals. At its core, a social group is defined by collective objectives that bind members together, fostering a sense of identity and purpose. For political parties, these goals are typically ideological, policy-driven, or centered on societal change. The Democratic Party in the United States, for instance, unites members through shared goals like expanding healthcare access and promoting environmental sustainability. Similarly, the Conservative Party in the UK rallies around goals such as fiscal responsibility and national sovereignty. These objectives serve as the glue that transforms a collection of individuals into a cohesive social entity.

To classify political parties as social groups, one must apply specific criteria rooted in the nature of shared goals. First, the goals must be explicit and collective, articulated in party platforms or manifestos. Second, they must transcend individual interests, prioritizing the group’s vision over personal ambitions. Third, these goals should drive collective action, whether through campaigning, legislation, or community organizing. For example, the Green Party’s global focus on combating climate change not only defines its identity but also mobilizes members across diverse regions. Without such unifying objectives, a political party risks becoming a mere coalition of self-interested actors rather than a social group.

A comparative analysis reveals that not all political parties meet these criteria equally. While some, like Germany’s Christian Democratic Union, maintain clear, long-standing goals that foster strong group identity, others, such as populist movements, often rely on transient or vague objectives. The latter may struggle to qualify as social groups because their goals lack the stability and depth required for sustained collective identity. This distinction highlights the importance of goal clarity and longevity in classifying political parties as social groups. Parties with well-defined, enduring goals are more likely to cultivate a sense of belonging and shared purpose among members.

Practically, understanding this classification has implications for political strategy and societal cohesion. Parties aiming to strengthen their social group identity should prioritize goal articulation and member engagement. For instance, holding regular town halls or workshops to discuss and refine party objectives can deepen members’ commitment. Additionally, cross-party collaborations on shared goals, such as bipartisan efforts on infrastructure development, can demonstrate the social group nature of political parties by showcasing their ability to unite for collective aims. By focusing on shared goals, political parties can transcend their role as power-seeking entities and function as meaningful social groups.

In conclusion, classifying political parties as social groups requires a rigorous examination of their shared goals. These goals must be explicit, collective, and action-oriented, fostering a sense of identity and purpose among members. By applying these criteria, we can distinguish between parties that function as cohesive social groups and those that operate as loose alliances. This framework not only enriches our understanding of political parties but also offers practical insights for strengthening their social cohesion and impact.

UK vs. US Politics: Exploring Parallel Party Ideologies and Structures

You may want to see also

Membership Dynamics: How party membership fosters social cohesion and collective identity among individuals

Political parties are often likened to social groups, but their membership dynamics reveal a deeper, more intricate relationship. Joining a political party isn’t merely about aligning with a set of policies; it’s an act of social integration. Members are bound by shared values, goals, and often, a sense of belonging that transcends individual interests. This collective identity is cultivated through rituals, such as party meetings, campaigns, and shared victories or defeats, which reinforce a "we" mentality. For instance, the Democratic Party in the United States uses grassroots organizing and local chapters to create micro-communities where members feel heard and valued, fostering cohesion.

Consider the mechanics of this cohesion. Party membership often involves structured roles—from local volunteers to national delegates—that give individuals a sense of purpose within the group. These roles are not just functional; they are symbolic, signaling commitment and earning social capital within the party. For example, in Germany’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU), members who actively participate in policy debates or campaign efforts are more likely to be elected to leadership positions, creating a feedback loop of engagement and loyalty. This structured participation mirrors the dynamics of social groups, where roles and contributions define one’s standing.

However, fostering collective identity isn’t without challenges. Parties must balance ideological purity with inclusivity to avoid alienating members. The Labour Party in the UK, for instance, has grappled with internal divisions between centrists and socialists, threatening cohesion. To mitigate this, parties often employ strategies like consensus-building workshops or diversity training, ensuring that members feel their voices are respected despite differences. A practical tip for party leaders: regularly survey members to identify fissures and address them proactively, ensuring unity without uniformity.

The psychological underpinnings of party membership further illuminate its social group nature. Research shows that individuals who identify strongly with a political party exhibit higher levels of group loyalty and are more likely to engage in collective action. This phenomenon is amplified during elections, when members rally around a common cause, creating a surge of solidarity. For example, during the 2020 U.S. presidential campaign, both Democratic and Republican volunteers reported increased feelings of camaraderie, even across demographic divides. This emotional investment is a key driver of social cohesion, turning a political affiliation into a social identity.

Finally, the longevity of party membership plays a critical role in sustaining collective identity. Unlike transient social groups, political parties often span generations, creating intergenerational bonds. In India, the Indian National Congress has members whose families have been affiliated with the party for decades, passing down values and traditions. This continuity reinforces the party’s identity as a social institution, not just a political entity. For individuals, long-term membership offers a sense of stability and heritage, deepening their commitment. Parties can nurture this by creating mentorship programs or legacy initiatives that connect older and younger members, ensuring the collective identity endures.

When Does the Political Debate Start? Key Timing Details Revealed

You may want to see also

Social Interaction: Role of party activities in creating social bonds and networks among members

Political parties are often seen as vehicles for ideological advocacy and policy change, but their role as social groups is equally significant. Party activities—rallies, fundraisers, canvassing, and local meetings—serve as structured opportunities for members to interact, fostering a sense of belonging and shared purpose. These events are not merely transactional; they are social rituals that strengthen interpersonal bonds through repeated, meaningful engagement. For instance, door-to-door canvassing pairs members together, creating natural opportunities for conversation and camaraderie, while post-event debriefs often evolve into informal social gatherings. Such activities transform abstract political goals into tangible, shared experiences, embedding members within a network of like-minded individuals.

Consider the mechanics of these interactions: party activities are designed to be collaborative, requiring members to work toward a common objective. This shared effort activates psychological principles like the "mere exposure effect," where repeated contact increases liking, and the "sweat equity effect," where effort invested in a group enhances commitment. For example, organizing a community rally involves tasks like flyer distribution, stage setup, and volunteer coordination. Each role, no matter how small, contributes to a collective achievement, reinforcing social ties. Practical tip: Party organizers should intentionally rotate leadership roles during events to ensure all members feel valued and connected, not just those in prominent positions.

A comparative analysis reveals that political parties differ from other social groups in their ability to blend personal relationships with civic engagement. Unlike book clubs or sports teams, party activities explicitly link social interaction with broader societal impact. This dual function makes the bonds formed within parties particularly resilient. Members are not just friends; they are co-creators of change. For instance, a study of local party chapters found that members who participated in both policy discussions and social events reported higher levels of trust and loyalty than those who engaged in only one type of activity. Caution: Overemphasis on political discourse at the expense of social interaction can alienate newer or less ideologically rigid members, so balance is key.

To maximize the social bonding potential of party activities, organizers should adopt a multi-faceted approach. First, incorporate icebreaker-style elements into political events to ease initial interactions, such as pairing newcomers with seasoned members during canvassing. Second, create low-stakes social events like potlucks or game nights to complement high-intensity political activities. Third, leverage digital platforms to maintain connections between in-person meetings, such as dedicated Slack channels or WhatsApp groups for casual conversation. Finally, acknowledge and celebrate milestones—both personal and political—to reinforce the group’s collective identity. By treating social interaction as a strategic component of party life, organizers can transform members from passive participants into an interconnected, committed community.

Understanding Political Parties: A Simple Kid-Friendly Definition Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Cultural Influence: Impact of political parties on shaping societal norms, values, and cultural practices

Political parties are not merely vehicles for policy implementation; they are cultural architects, subtly but profoundly shaping the norms, values, and practices that define societies. Consider how the Democratic Party in the United States has championed LGBTQ+ rights, from advocating for marriage equality to promoting inclusive education policies. This sustained political effort has not only changed laws but also normalized acceptance and celebration of diverse sexual orientations and gender identities, reshaping cultural attitudes over decades. Conversely, the Republican Party’s emphasis on traditional family structures has reinforced conservative values in certain regions, influencing everything from local school curricula to community events. These examples illustrate how political parties act as catalysts for cultural evolution, embedding their ideologies into the fabric of daily life.

To understand this dynamic, examine the role of political messaging in framing societal priorities. Parties use rhetoric, symbolism, and policy proposals to elevate specific values—whether individualism, collectivism, environmental stewardship, or religious observance. For instance, the Green Party in Germany has successfully mainstreamed sustainability, not just through legislation but by embedding eco-consciousness into cultural practices, from recycling habits to public transportation use. This demonstrates that political parties do not merely reflect cultural trends; they actively construct them by amplifying certain narratives and marginalizing others. Their ability to control platforms, such as media outlets or public institutions, allows them to disseminate their vision of society, often with lasting impact.

However, this cultural influence is not without risks. When political parties prioritize ideological purity over inclusivity, they can fracture societies rather than unite them. The rise of populist parties across Europe, for example, has often been accompanied by a resurgence of nationalism and xenophobia, challenging multicultural norms and fostering division. Such parties exploit cultural anxieties, reshaping societal values in ways that can undermine social cohesion. This underscores the dual-edged nature of their influence: while they can drive progressive change, they can also entrench regressive practices, depending on the ideologies they promote.

Practical steps to mitigate these risks include fostering cross-party collaborations on cultural issues and encouraging citizens to critically engage with political narratives. For instance, inter-party initiatives promoting civic education can help individuals discern between constructive cultural shifts and harmful propaganda. Additionally, supporting independent media and grassroots movements can counterbalance the monopolization of cultural discourse by dominant parties. By diversifying the sources of cultural influence, societies can ensure that political parties remain one of many voices shaping norms and values, rather than the sole arbiters of cultural identity.

In conclusion, political parties are undeniably social groups with the power to mold cultural landscapes. Their influence extends beyond policy, permeating the everyday lives of citizens through the values they promote and the practices they normalize. Recognizing this dynamic empowers individuals to hold parties accountable for their cultural impact and to actively participate in shaping the societal norms that define their communities. Whether through progressive reform or conservative preservation, political parties remain indispensable actors in the ongoing negotiation of cultural identity.

Global Political Challenges: Unraveling the Complex Web of World Problems

You may want to see also

Exclusion vs. Inclusion: How parties can act as both inclusive communities and exclusive social groups

Political parties inherently straddle the line between inclusion and exclusion, embodying a paradox that shapes their identity and function. On one hand, they serve as inclusive communities, rallying individuals around shared ideals, fostering collective action, and amplifying marginalized voices. For instance, the Democratic Party in the U.S. has historically positioned itself as a coalition of diverse groups—racial minorities, women, LGBTQ+ individuals—united under progressive principles. Such inclusivity strengthens democratic participation by providing a platform for underrepresented populations. Yet, this inclusivity is often superficial, as internal power dynamics frequently marginalize the very groups the party claims to champion, revealing the tension between rhetoric and reality.

Exclusion, however, is equally baked into the DNA of political parties. Membership often requires adherence to a specific ideology, policy agenda, or even cultural norms, effectively alienating those who deviate. Consider the Republican Party’s emphasis on conservative values, which excludes progressives and moderates. More insidiously, parties may employ exclusionary tactics like voter suppression, gerrymandering, or restrictive membership criteria to consolidate power. For example, some parties in Europe have historically barred immigrants or religious minorities from full participation, reinforcing social hierarchies. This duality highlights how parties can simultaneously claim to be inclusive while perpetuating exclusion through structural and ideological mechanisms.

The interplay between inclusion and exclusion is further complicated by the strategic nature of party politics. Parties often adopt inclusive rhetoric during elections to broaden their appeal, only to revert to exclusionary practices once in power. Take the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa, which mobilized diverse groups under the banner of anti-apartheid struggle but later faced criticism for neglecting the economic needs of its Black constituency. Such contradictions underscore the transactional nature of party inclusivity, where unity is often a means to an end rather than a genuine commitment to equality.

To navigate this paradox, parties must adopt deliberate strategies that prioritize substantive inclusion over tokenism. This involves dismantling internal barriers to leadership for marginalized groups, ensuring policy agendas reflect diverse needs, and fostering grassroots engagement. For instance, Spain’s Podemos party has implemented quotas for women and minority representation in leadership roles, setting a precedent for meaningful inclusivity. Conversely, parties must also acknowledge the necessity of exclusion in certain contexts—such as rejecting extremist ideologies—to maintain coherence and integrity.

Ultimately, the dual nature of political parties as both inclusive communities and exclusive social groups is not a flaw but a feature of their role in democratic systems. By embracing this complexity, parties can strive to balance unity with diversity, ensuring they remain relevant and equitable in an increasingly polarized world. The challenge lies in aligning their inclusive ideals with exclusionary practices, fostering a politics that truly serves all.

Can Political Parties Be Formed Without Money? Exploring the Financial Reality

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, a political party is often considered a social group because it brings together individuals with shared political beliefs, values, and goals, fostering collective identity and social interaction.

A political party is defined as a social group by its structured organization, shared ideology, and the social bonds formed among its members through common political activities and objectives.

While theoretically possible, a political party typically relies on social cohesion and collective action to achieve its goals, making its social group dynamics essential for effective functioning.

A political party differs from other social groups primarily in its focus on influencing government policies and holding political power, whereas other social groups may center around cultural, recreational, or personal interests.