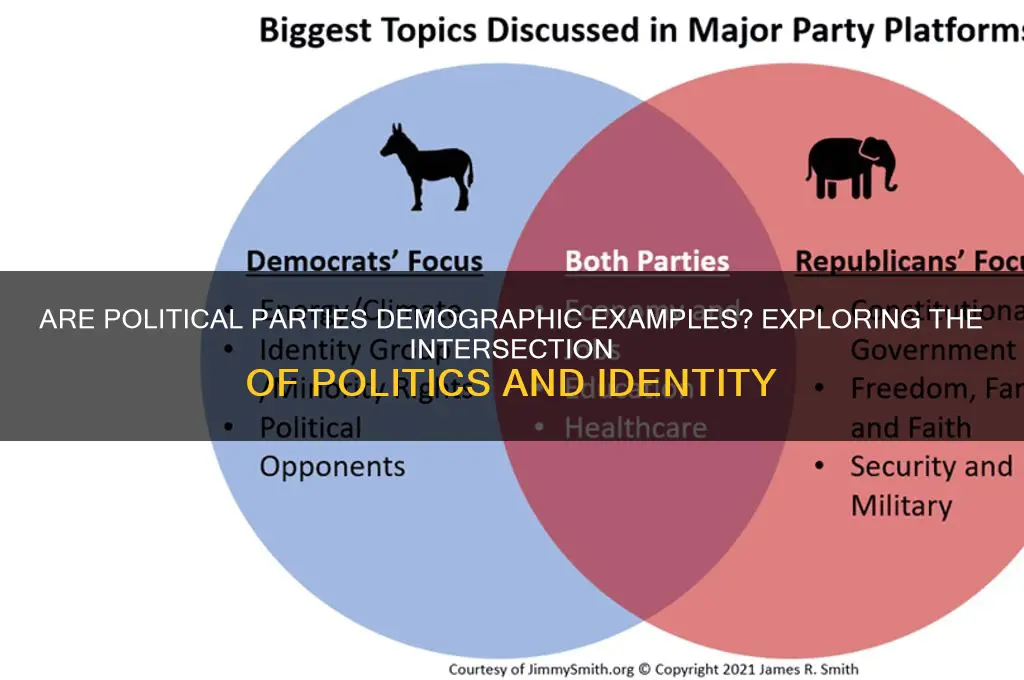

The question of whether a political party can be considered a demographic example is a nuanced one, as it intersects the realms of political science and sociology. While demographics typically refer to statistical data about populations, such as age, gender, race, or income, political parties are organizations that represent ideologies, interests, or policy agendas. However, political parties often attract and mobilize specific demographic groups based on shared values or concerns, effectively becoming proxies for certain segments of society. For instance, a party advocating for workers' rights may predominantly appeal to lower-income or unionized demographics, while another focused on environmental policies might resonate more with younger, urban populations. In this sense, political parties can function as demographic examples by reflecting the collective identities and priorities of the groups they represent, even though they are not demographics in the traditional sense.

Explore related products

$14.97 $32.99

What You'll Learn

- Defining Demographics: Understanding demographics as statistical data about populations, not organizations like political parties

- Party Membership vs. Demographics: Analyzing if party members represent a specific demographic group

- Voting Patterns: Examining if party supporters align with particular demographic characteristics

- Policy Influence: Exploring how demographic factors shape party platforms and priorities

- Demographic Targeting: Investigating if parties tailor strategies to appeal to specific demographics

Defining Demographics: Understanding demographics as statistical data about populations, not organizations like political parties

Demographics are the backbone of understanding populations, but they are often misunderstood or misapplied. At their core, demographics refer to statistical data that describe the characteristics of a population, such as age, gender, income, education, and geographic location. These data points are essential for policymakers, marketers, and researchers to make informed decisions. However, a common misconception arises when people conflate demographics with organizations, like political parties. A political party is not a demographic; it is an entity composed of individuals who share certain beliefs or goals. Demographics, on the other hand, are about quantifiable traits of groups, not their affiliations or ideologies.

To illustrate, consider a political party’s membership. While a party may attract a specific age group or income bracket, the party itself is not a demographic category. For instance, if 60% of a party’s members are aged 18–35, this statistic is demographic data about the party’s membership, not a definition of the party itself. The confusion often stems from using demographic data to analyze or describe a party’s base, but the party remains an organization, not a demographic group. This distinction is crucial for accurate analysis and communication.

Understanding this difference is vital for practical applications. For example, a marketer targeting young voters might analyze demographic data (e.g., age distribution, education levels) to craft a campaign. However, they would not label a political party as a demographic target. Instead, they would use demographic insights to identify *within* which groups the party’s supporters are likely to be found. This approach ensures precision and avoids oversimplification. Similarly, policymakers might examine demographic trends to address issues like healthcare or education, but they would not treat political parties as demographic variables in their models.

A useful analogy is to think of demographics as ingredients in a recipe. Just as flour, sugar, and eggs are components of a cake, age, gender, and income are components of a population. A political party, however, is like a cookbook—a collection of recipes (or members) that uses these ingredients. The cookbook itself is not an ingredient; it is a tool that organizes and presents the ingredients in a specific way. This analogy highlights the importance of distinguishing between the data (demographics) and the structures (organizations) that utilize it.

In practice, clarity around this distinction can prevent errors in research and decision-making. For instance, a survey analyzing voter behavior should categorize respondents by demographic traits (e.g., age, income) rather than lumping them under a political party label. This ensures the data remains focused on population characteristics, not organizational affiliations. By adhering to this principle, professionals can produce more accurate insights and avoid conflating the statistical with the structural. Demographics are about *who* and *what*, not *where* allegiances lie.

Why Late-Night TV Shows Have Become Political Battlegrounds

You may want to see also

Party Membership vs. Demographics: Analyzing if party members represent a specific demographic group

Political parties often claim to represent the interests of specific demographic groups, but does their membership actually reflect these claims? A closer look at party membership demographics reveals a complex relationship between political affiliation and identity. For instance, in the United States, the Democratic Party is frequently associated with younger voters, racial minorities, and urban residents, while the Republican Party is linked to older, white, and rural populations. However, these generalizations may oversimplify the reality. A 2021 Pew Research Center study found that while 56% of Black Americans identify with the Democratic Party, 10% affiliate with the Republican Party, and 33% are independents. This data suggests that even within a demographic group, political preferences can vary significantly.

To analyze whether party members represent a specific demographic, consider the following steps: First, identify the demographic characteristics of a party’s membership base through surveys, voter registration data, and exit polls. Second, compare these characteristics to the broader population to determine if the party’s membership is disproportionately skewed toward certain groups. For example, in the UK, Labour Party members are more likely to be under 40, while Conservative Party members tend to be older. Third, examine the party’s policy priorities and messaging to assess if they align with the needs and values of their dominant demographic groups. A party that claims to represent working-class voters but focuses primarily on corporate tax cuts may face credibility issues.

One cautionary note: relying solely on demographic data can lead to stereotypes and overlook individual motivations. Not all young people vote Democrat, nor do all older individuals support Republican policies. Personal experiences, socioeconomic status, and regional influences also play critical roles. For instance, a young, rural voter might align with conservative values due to their community’s agricultural focus, despite their age group’s general leftward lean. Therefore, while demographics provide a useful starting point, they should not be the sole lens through which party representation is analyzed.

A persuasive argument can be made that parties should actively diversify their membership to better reflect the population they aim to serve. This involves targeted recruitment efforts, inclusive policies, and grassroots engagement. For example, the German Green Party has successfully attracted younger members by emphasizing climate action and digital engagement. Conversely, parties that fail to adapt risk becoming increasingly disconnected from the electorate. A practical tip for parties is to conduct regular demographic audits of their membership and adjust outreach strategies accordingly.

In conclusion, while party membership often correlates with specific demographic groups, this relationship is neither absolute nor static. Parties must balance representing their core constituencies with appealing to a broader electorate. By critically examining membership demographics and aligning policies with diverse needs, parties can foster genuine representation and maintain relevance in an ever-changing political landscape.

Neil Young's Political Stance: Liberal Activism and Social Commentary Explored

You may want to see also

Voting Patterns: Examining if party supporters align with particular demographic characteristics

Political parties often attract supporters from specific demographic groups, creating a mosaic of voting patterns that reflect societal divisions and priorities. For instance, in the United States, the Democratic Party tends to draw stronger support from younger voters, particularly those aged 18–29, while the Republican Party traditionally appeals more to older demographics, such as those over 65. This age-based divide is not merely coincidental but often correlates with differing stances on issues like healthcare, climate change, and social security. Analyzing these patterns reveals how political parties inadvertently become demographic proxies, representing the interests and values of their most loyal constituencies.

To examine these alignments, consider the role of education levels. College-educated voters in many Western countries, including the U.K. and Canada, are more likely to support left-leaning parties, whereas those without a college degree often lean toward conservative parties. This trend is particularly pronounced in the U.S., where the Democratic Party has seen a significant shift toward highly educated urban voters, while the Republican Party has solidified its base among rural and less-educated populations. Such patterns suggest that political affiliation is not just a matter of ideology but also a reflection of socioeconomic and cultural identities.

However, caution is warranted when interpreting these correlations. Demographic alignment does not imply uniformity within a party’s base. For example, while the Democratic Party in the U.S. is often associated with racial minorities, there are notable exceptions, such as Hispanic voters in Florida, who have shown increasing support for Republicans in recent elections. Similarly, gender-based voting patterns are not absolute; while women are more likely to vote for left-leaning parties in many countries, this trend varies significantly by region, religion, and socioeconomic status. These nuances highlight the complexity of demographic-party relationships and the need for granular analysis.

Practical steps for understanding these patterns include examining exit polls, census data, and longitudinal studies that track voter behavior over time. For instance, the Pew Research Center’s analyses of U.S. elections provide detailed breakdowns of voting patterns by age, race, income, and education. By cross-referencing such data with party platforms and campaign strategies, researchers and policymakers can identify which demographics are being effectively targeted—and which are being overlooked. This approach not only sheds light on the demographic makeup of party supporters but also informs strategies for broadening political appeal.

Ultimately, the alignment of party supporters with demographic characteristics is both a reflection of societal divisions and a driver of political polarization. While these patterns offer valuable insights into voter behavior, they also risk reinforcing stereotypes and limiting the diversity of political discourse. Recognizing this duality is essential for fostering inclusive politics that transcend demographic boundaries. By understanding these dynamics, voters, parties, and analysts can work toward a more nuanced and equitable political landscape.

Understanding Political Party Machines: Power, Influence, and Operations Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$30.56 $14.95

Policy Influence: Exploring how demographic factors shape party platforms and priorities

Demographic factors act as a compass for political parties, guiding their policy platforms and priorities. Consider the Democratic Party in the United States, which has increasingly tailored its agenda to address the concerns of younger voters, such as student loan forgiveness and climate change. This shift reflects the growing political influence of millennials and Gen Z, who now constitute a significant portion of the electorate. Conversely, the Republican Party often emphasizes policies like Social Security reform and tax cuts, which resonate more with older demographics. This strategic alignment demonstrates how parties adapt their platforms to appeal to specific age groups, recognizing that demographic composition directly impacts electoral success.

To understand this dynamic, examine how parties analyze demographic data to identify key voter segments. For instance, a party might use census data to determine that a particular district has a high concentration of working-class families. Armed with this information, the party could prioritize policies like affordable childcare or wage increases, knowing these issues are likely to mobilize this demographic. This data-driven approach is not limited to age or socioeconomic status; it extends to race, ethnicity, and geographic location. For example, the rise of Latino voters in states like Texas and Arizona has prompted both major U.S. parties to invest in Spanish-language outreach and immigration reform proposals. Such targeted efforts illustrate how demographics shape not only what policies are proposed but also how they are communicated.

However, relying too heavily on demographic tailoring carries risks. Parties must balance appealing to specific groups without alienating others. For instance, a platform overly focused on urban issues might neglect rural voters, leading to fragmentation within the party’s base. To mitigate this, parties often adopt "umbrella policies" that address multiple demographic concerns simultaneously. The Affordable Care Act in the U.S. is an example: it targeted younger voters with provisions like staying on parental insurance until age 26, while also addressing the needs of older adults through Medicare expansion. This approach ensures broader appeal while still leveraging demographic insights.

Practical steps for parties seeking to align their platforms with demographic trends include conducting regular voter surveys, collaborating with community leaders, and using predictive analytics to forecast shifts in population dynamics. For instance, a party might partner with local organizations in rapidly growing suburban areas to understand emerging concerns, such as infrastructure or school funding. Additionally, parties should avoid tokenism by ensuring that demographic representation within their leadership mirrors the diversity of their voter base. This internal alignment fosters credibility and strengthens the connection between policy priorities and the lived experiences of constituents.

In conclusion, demographic factors are not just descriptors of a population but active forces shaping political agendas. Parties that master the art of translating demographic data into actionable policies gain a competitive edge. Yet, this process requires nuance, balance, and a commitment to inclusivity. By strategically aligning platforms with the needs of specific groups while maintaining broad appeal, parties can navigate the complex interplay between demographics and policy influence effectively.

Is Southern Methodist University Politically Affiliated? Exploring the Party Debate

You may want to see also

Demographic Targeting: Investigating if parties tailor strategies to appeal to specific demographics

Political parties often segment their messaging to resonate with distinct voter groups, a practice rooted in demographic targeting. This strategy involves analyzing age, gender, race, income, education, and geographic location to craft tailored appeals. For instance, a party might emphasize student loan forgiveness to attract young voters aged 18–29, while focusing on Social Security reforms to engage seniors aged 65 and above. Such precision is evident in campaign ads, policy proposals, and even the selection of rally locations, where data-driven decisions aim to maximize influence within specific demographics.

Consider the 2020 U.S. presidential election, where both major parties employed demographic targeting with surgical precision. Democrats targeted suburban women by highlighting healthcare and education, while Republicans focused on rural, white, non-college-educated males with messages about economic nationalism. This approach extends globally: in India, the BJP leverages religious and caste identities, while the UK Labour Party tailors policies to appeal to urban, multicultural voters. These examples illustrate how demographic targeting is not just a tactic but a cornerstone of modern political strategy.

However, demographic targeting is not without risks. Over-reliance on segmentation can lead to polarizing campaigns that alienate broader audiences. For example, a party focusing exclusively on younger voters might neglect the concerns of older demographics, fostering generational divides. Additionally, critics argue that such strategies can perpetuate stereotypes, reducing complex voter identities to simplistic categories. Parties must balance precision with inclusivity, ensuring their messaging does not exclude or marginalize unintended groups.

To implement demographic targeting effectively, parties should follow a three-step process: 1) Data Collection—gather voter information through polls, social media analytics, and census data; 2) Segmentation—categorize voters into distinct groups based on shared characteristics; 3) Customization—develop targeted messages, policies, and outreach strategies for each segment. For instance, a party might use Instagram ads to reach millennials while relying on local radio to engage older voters. Caution must be exercised to avoid data privacy violations and ensure transparency in targeting methods.

In conclusion, demographic targeting is a double-edged sword in political strategy. When executed thoughtfully, it allows parties to connect with voters on a personal level, addressing their unique needs and concerns. Yet, it demands ethical considerations and a commitment to inclusivity. As political landscapes evolve, the ability to balance precision with broad appeal will determine the success of this approach in shaping electoral outcomes.

Understanding Splinter Parties: Political Breakaways and Their Impact Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, a political party is not a demographic example. Demographics refer to statistical data about populations, such as age, gender, race, or income, while a political party is an organized group with shared political goals and ideologies.

Yes, political party affiliation can be included in demographic analysis as a categorical variable, but it does not define demographics itself. It is often used to understand voter behavior or political trends within specific demographic groups.

A political party is not classified as a demographic because it represents a choice or affiliation based on ideology, not inherent characteristics like age, gender, or ethnicity, which are the core elements of demographic classification.