The question of whether a faction is the same as a political party is a nuanced one, rooted in the distinctions between their structures, goals, and historical contexts. Factions, often informal and internal to larger organizations, typically represent specific interests or ideologies within a broader group, such as a political party or government. In contrast, political parties are formal, organized entities with defined platforms, leadership, and mechanisms for participating in elections and governance. While both can advocate for particular agendas, factions lack the institutional framework and public-facing role that define political parties, making them distinct yet interconnected concepts in the realm of political organization.

Explore related products

$42.55 $55.99

$23.95 $39.95

What You'll Learn

- Definition of Faction: Small group within a larger one, sharing specific interests or goals, not always formal

- Definition of Political Party: Organized group seeking political power, typically through elections and governance

- Key Differences: Factions lack formal structure; parties have hierarchy, platforms, and public presence

- Overlap and Examples: Factions can exist within parties (e.g., Tea Party in GOP)

- Purpose and Scope: Parties aim for national power; factions focus on narrower, specific agendas

Definition of Faction: Small group within a larger one, sharing specific interests or goals, not always formal

A faction, by definition, is a small group within a larger organization, united by specific interests or goals that may not align with the broader group's objectives. This distinction is crucial when comparing factions to political parties. While both involve collective action, factions are often less formal, more fluid, and focused on narrower agendas. For instance, within a labor union, a faction might advocate for stricter workplace safety measures, whereas the union as a whole may prioritize wage negotiations. This example illustrates how factions operate as specialized subunits, driving change from within without necessarily representing the entire group.

To understand the difference, consider the structure and purpose. Political parties are formalized entities with established hierarchies, platforms, and membership criteria, designed to compete for political power. Factions, however, are often informal and transient, emerging in response to specific issues or leadership disputes. In the Democratic Party, for example, the Progressive Caucus acts as a faction, pushing for policies like Medicare for All, while the party itself maintains a broader, more inclusive platform. This dynamic highlights how factions can influence larger organizations without becoming synonymous with them.

One practical takeaway is that factions are tools for amplifying specific voices within a larger group. If you’re part of a community organization, forming a faction can help advance targeted goals without splintering the group. For instance, a faction within a school PTA focused on increasing arts funding could draft a detailed proposal, gather support, and present it to the broader membership. This approach ensures that niche interests are addressed while maintaining unity. However, caution is necessary: factions can sometimes escalate internal conflicts if not managed carefully, so clear communication and respect for the larger group’s mission are essential.

Comparatively, while political parties aim to represent diverse interests under a unified banner, factions thrive on specificity. A political party might cater to both environmentalists and industrialists, but a faction within that party could exclusively champion green energy policies. This specialization allows factions to act as catalysts for change, pushing the larger group to evolve. For those seeking to drive targeted reform, understanding this distinction is key: join a party to participate in the political process, but form a faction to sharpen its focus on your priorities.

Finally, the informal nature of factions offers both flexibility and challenges. Unlike political parties, factions are not bound by rigid structures, allowing them to adapt quickly to new issues. However, this lack of formality can also lead to instability or marginalization if not strategically managed. For example, a faction within a tech company advocating for remote work policies might gain traction during a pandemic but lose influence as circumstances change. To maximize impact, factions should document their goals, build coalitions, and align their efforts with the broader group’s long-term interests, ensuring their voice remains relevant and constructive.

Is GetUp! a Political Party? Unraveling Its Role and Influence

You may want to see also

Definition of Political Party: Organized group seeking political power, typically through elections and governance

A political party, by definition, is an organized group with a shared ideology that seeks to gain political power, typically through elections and governance. This distinguishes it from factions, which are often internal subgroups within a larger organization, including political parties themselves. While both entities can advocate for specific agendas, a political party operates as a formal, structured entity with a broader reach and a defined mechanism for achieving power—elections. Factions, on the other hand, may lack this formal structure and are often more fluid, focusing on influencing policy or leadership from within.

Consider the Democratic Party in the United States, which is a political party with a national presence, a formal platform, and a mechanism for nominating candidates for public office. Within this party, factions like the Progressive Caucus or the Blue Dog Coalition exist, advocating for specific ideological positions. These factions do not seek to replace the party but to shape its direction from within. This example illustrates the hierarchical relationship: a political party is the overarching entity, while factions are its internal components, often competing for influence rather than power in the broader political system.

To understand the distinction further, examine the organizational requirements of a political party. It must register with electoral authorities, adhere to legal frameworks, and mobilize resources for campaigns. Factions, however, operate with fewer formalities, often relying on informal networks and shared interests. For instance, the Tea Party movement in the U.S. began as a faction within the Republican Party but lacked the formal structure of a political party, though it significantly influenced Republican policy and candidate selection. This highlights the party’s role as a structured vehicle for power, whereas factions are more about internal advocacy.

Practical distinctions also emerge in their strategies. A political party focuses on winning elections, crafting policy, and governing, requiring a broad appeal to diverse voter groups. Factions, in contrast, often target niche issues or ideological purity, which can limit their appeal but deepen their influence within a party. For example, the Green Party in Germany operates as a political party with a clear environmental focus, while factions within the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) might push for specific economic or social policies. This shows how parties balance broad governance goals, while factions prioritize narrower agendas.

In conclusion, while both political parties and factions are driven by shared ideologies, their structures, goals, and mechanisms for influence differ significantly. A political party is a formal organization designed to seek and wield power through elections and governance, whereas a faction is an internal group aiming to shape the direction of a larger entity. Recognizing this distinction is crucial for understanding political dynamics, as it clarifies how power is pursued and exercised within democratic systems.

Understanding Political Party Ads for Kids in Washington: A Simple Guide

You may want to see also

Key Differences: Factions lack formal structure; parties have hierarchy, platforms, and public presence

Factions and political parties often blur in public discourse, yet their structural foundations sharply diverge. A faction typically emerges as an informal grouping united by shared interests or ideologies, lacking the rigid frameworks that define political parties. Consider the Tea Party movement in the United States, which operated as a faction within the Republican Party, advocating for specific fiscal policies without establishing a formal hierarchy or registering as a separate entity. In contrast, political parties like the Democratic or Republican Parties in the U.S. have clear leadership structures, from local committees to national chairpersons, ensuring coordinated action and decision-making.

The absence of formal structure in factions allows for flexibility but limits their ability to project sustained influence. Factions often rely on charismatic leaders or grassroots mobilization, making their longevity dependent on individual efforts or transient issues. For instance, the anti-war factions within the U.K. Labour Party during the Iraq War lacked a permanent organizational framework, which hindered their ability to shape policy beyond the immediate crisis. Political parties, however, institutionalize their presence through platforms, bylaws, and public outreach, ensuring continuity even as individual leaders or issues fade.

Hierarchy is another distinguishing feature. Political parties operate as pyramids, with defined roles for members, from rank-and-file supporters to elected officials. This hierarchy facilitates strategic planning, resource allocation, and accountability. Factions, on the other hand, often resemble networks rather than pyramids, with fluid roles and decentralized decision-making. While this can foster inclusivity, it also risks fragmentation, as seen in the Occupy Wall Street movement, where the lack of a clear leadership structure ultimately limited its political impact.

Platforms and public presence further differentiate the two. Political parties articulate comprehensive policy agendas, vetted through conventions and publicized to attract voters. For example, the Green Party in Germany has a detailed platform addressing climate change, economic justice, and social equality, which it promotes through campaigns and media engagement. Factions, however, tend to focus on narrower issues or ideological purity, often eschewing the compromises necessary for broad-based appeal. This narrow focus can make factions effective in mobilizing specific constituencies but less capable of governing or winning elections independently.

In practice, understanding these differences is crucial for navigating political landscapes. For activists, joining a faction may offer a platform for advocacy on specific issues, but aligning with a political party provides a structured pathway to influence policy and governance. For voters, recognizing whether a group operates as a faction or a party helps assess its capacity to deliver on promises. While factions can spark movements and challenge the status quo, parties remain the primary vehicles for translating ideas into actionable governance, underscoring the importance of structure in political effectiveness.

Is Russia Still Communist? Exploring Its Political Party Structure

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Overlap and Examples: Factions can exist within parties (e.g., Tea Party in GOP)

Factions and political parties, while distinct in theory, often blur in practice. A faction is a subgroup within a larger organization, united by shared beliefs or goals that may diverge from the broader group's platform. Political parties, on the other hand, are formal organizations with established structures, platforms, and mechanisms for contesting elections. The key difference lies in scope and formality: parties operate as independent entities, while factions are internal to them. However, this distinction is not always clear-cut, as factions can wield significant influence, shaping party policies and public perception.

Consider the Tea Party movement within the Republican Party (GOP) in the United States. Emerging in the late 2000s, the Tea Party was not a separate political party but a faction advocating for limited government, lower taxes, and fiscal conservatism. Despite lacking formal party status, it mobilized grassroots support, influenced GOP primaries, and pushed the party's agenda to the right. This example illustrates how factions can act as catalysts for change within parties, often amplifying specific ideologies or issues. The Tea Party's success in electing aligned candidates demonstrates the power of factions to reshape a party's identity and electoral strategy.

Analyzing the dynamics between factions and parties reveals a symbiotic yet contentious relationship. Factions provide parties with energy, activism, and a clear ideological focus, which can be crucial for mobilizing voters. However, they can also create internal divisions, as seen in the GOP's struggles to balance Tea Party demands with broader electoral appeal. Parties must navigate these tensions carefully, as factions can either strengthen or fracture their unity. For instance, while the Tea Party invigorated the GOP base, it also contributed to legislative gridlock and alienated moderate voters.

Practical takeaways for understanding this overlap include recognizing factions as both opportunities and challenges for parties. Parties can harness faction energy by incorporating their priorities into platforms without alienating other constituencies. Conversely, factions must balance ideological purity with pragmatism to remain effective. For observers, tracking faction-party interactions offers insights into a party's evolution and its responsiveness to internal and external pressures. The Tea Party's rise and eventual integration into the GOP's mainstream highlight how factions can leave lasting imprints on their host parties.

In conclusion, the overlap between factions and political parties is a dynamic and nuanced phenomenon. Factions like the Tea Party demonstrate how internal groups can drive significant change, even without formal party status. Understanding this relationship requires examining how factions influence party agendas, elections, and internal cohesion. By doing so, one gains a clearer picture of the complexities within political organizations and the forces that shape their trajectories.

Tocqueville's Vision: Defining Greatness in Political Parties and Democracy

You may want to see also

Purpose and Scope: Parties aim for national power; factions focus on narrower, specific agendas

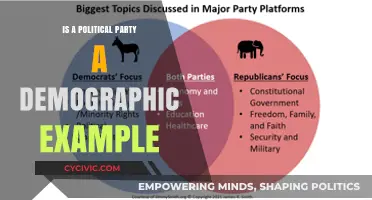

Political parties and factions both operate within the realm of politics, yet their goals and operational scopes differ significantly. Parties typically aim for national power, seeking to control governments, shape broad policies, and represent diverse constituencies. Their agendas are expansive, encompassing economic, social, and foreign policy issues that affect the entire nation. For instance, the Democratic and Republican parties in the United States compete for control of the presidency, Congress, and state governments, advocating for comprehensive platforms that address everything from healthcare to defense.

Factions, in contrast, focus on narrower, specific agendas. These groups often form within or alongside larger parties to champion particular causes or ideologies. For example, the Tea Party movement within the Republican Party emphasized fiscal conservatism and limited government, while environmental factions within the Democratic Party push for aggressive climate action. Factions are less concerned with achieving overall national power and more focused on influencing policy in their specific areas of interest. Their success is measured not by winning elections but by advancing their targeted goals.

This distinction in scope affects how these groups operate. Parties build broad coalitions, appealing to a wide range of voters with varied priorities. They must balance competing interests within their ranks to maintain unity and electoral viability. Factions, however, thrive on specialization and intensity. They mobilize dedicated supporters around a single issue or ideology, often using grassroots tactics to pressure larger parties into adopting their agenda. For instance, gun rights factions like the National Rifle Association (NRA) wield significant influence by focusing exclusively on Second Amendment issues.

Understanding this difference is crucial for navigating political landscapes. Parties are the architects of national governance, while factions are the catalysts for specific change. Voters and policymakers must recognize that supporting a party means endorsing a broad vision, whereas aligning with a faction involves committing to a narrower cause. This clarity helps in making informed decisions and appreciating the complex interplay between these two political entities.

In practice, the relationship between parties and factions can be symbiotic or contentious. Parties benefit from factions’ ability to energize specific voter bases, but they also risk being hijacked by extreme agendas. Factions, meanwhile, rely on parties for access to power but must guard against dilution of their core objectives. For individuals, engaging with both requires strategic thinking: joining a party for broad representation and supporting factions for targeted advocacy. This dual approach maximizes influence across the political spectrum.

Do Political Parties Cover Workers' Comp for Campaign Staff?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, a faction is not the same as a political party. A faction is a smaller group within a larger organization, such as a political party, that shares specific interests, goals, or ideologies. Political parties are broader organizations that represent a wider range of views and operate at a national or international level.

Yes, factions can exist outside of political parties. They can form within other organizations, such as corporations, social groups, or even informal communities, based on shared interests or objectives.

Not always. Factions may have agendas or priorities that differ from or even conflict with those of the larger political party they belong to, leading to internal divisions or debates.

Factions can play a role in representing diverse viewpoints within a political party, fostering debate, and ensuring that various interests are considered. However, they can also lead to internal conflicts if not managed effectively.