The phenomenon of political parties swapping ideologies, alliances, or voter bases is a complex and intriguing aspect of modern political dynamics. Historically, parties have evolved in response to shifting societal values, economic changes, and demographic trends, often leading to dramatic realignments. For instance, in the United States, the Democratic and Republican parties swapped their traditional stances on civil rights and economic policies during the mid-20th century, a process known as the Southern Strategy. Similarly, in Europe, the rise of populist movements has forced mainstream parties to recalibrate their positions on issues like immigration and globalization. Understanding how and why these swaps occur requires examining factors such as leadership shifts, electoral strategies, and the influence of external events, which collectively reshape the political landscape and redefine party identities.

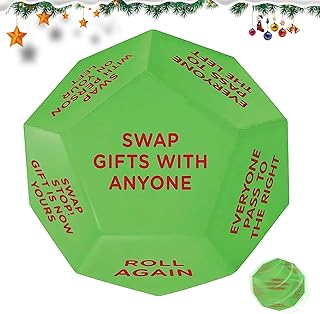

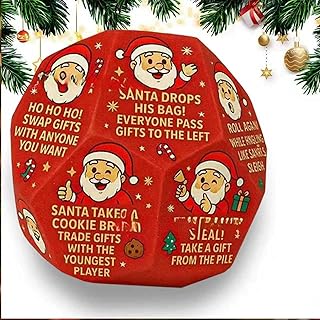

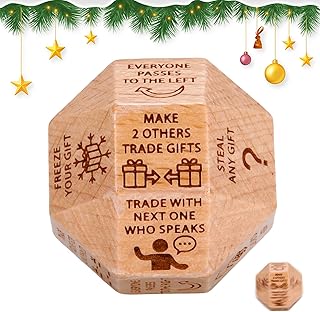

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Historical Context: Key events leading to major political party realignments in different countries

- Ideological Shifts: How parties change core beliefs to appeal to new voter demographics

- Leadership Changes: Impact of new leaders on party direction and voter perception

- Electoral Strategies: Tactics like gerrymandering or coalition-building that influence party dominance

- Social Movements: Role of grassroots movements in pushing parties to adopt new policies

Historical Context: Key events leading to major political party realignments in different countries

The American Civil War (1861–1865) catalyzed a seismic shift in U.S. party politics, effectively swapping the dominant issues and coalitions of the Republican and Democratic parties. Before the war, the Whigs and Democrats were the major parties, with slavery as a divisive but manageable issue. The war’s aftermath, however, saw the Republicans, who had opposed slavery, rise to national prominence, while the Democrats, associated with the Confederacy, were marginalized in the North. This realignment was cemented by the Reconstruction era, during which the Republican Party became the party of national unity and economic modernization, while the Democrats struggled to redefine themselves. The 1868 election of Ulysses S. Grant marked the consolidation of this new political order, illustrating how a single catastrophic event can rewrite the rules of party competition.

In the United Kingdom, the Great Depression of the 1930s forced a realignment that reshaped the Conservative and Labour parties’ roles. Prior to the crisis, the Conservatives dominated British politics, with Labour seen as a fringe movement. However, the economic collapse discredited the Conservatives’ laissez-faire policies, opening the door for Labour’s rise as the party of social welfare and economic intervention. The 1945 general election, which swept Clement Attlee’s Labour Party into power, marked the culmination of this shift. Labour’s implementation of the welfare state and nationalization policies redefined the political landscape, demonstrating how economic crises can act as accelerants for party realignment.

Post-apartheid South Africa provides a unique case of realignment driven by the end of a repressive regime. The 1994 elections, the first to include all races, saw the African National Congress (ANC) emerge as the dominant party, replacing the National Party, which had enforced apartheid. This swap was not merely a transfer of power but a fundamental redefinition of South African politics around issues of racial equality and economic justice. The ANC’s victory was less about policy platforms and more about moral legitimacy, highlighting how historical injustices can create conditions for rapid and dramatic party realignment.

In Japan, the collapse of the Liberal Democratic Party’s (LDP) single-party dominance in the 1990s was precipitated by a series of corruption scandals and economic stagnation. The LDP, which had ruled almost uninterrupted since 1955, lost its grip on power as voters sought alternatives. The Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) emerged as a viable opposition, winning the 2009 election. This realignment was driven by public disillusionment with the LDP’s cronyism and its failure to address Japan’s economic woes. The case underscores how internal decay and external pressures can force a once-dominant party to cede ground, even in a country with a strong tradition of political stability.

Finally, the rise of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) in Turkey illustrates how cultural and religious shifts can realign party politics. Founded in 2001, the AKP capitalized on public dissatisfaction with Turkey’s secular elite and economic mismanagement. By blending conservative Islamic values with neoliberal economic policies, the AKP displaced the traditional secular parties, winning a majority in the 2002 elections. This realignment reflected a broader societal shift toward religious identity as a political force, showing how cultural changes can upend established party systems. Each of these examples reveals that party realignments are often the result of specific, high-impact events that force societies to reevaluate their political priorities.

Unveiling the Kraken: Understanding Its Role in Modern Political Discourse

You may want to see also

Ideological Shifts: How parties change core beliefs to appeal to new voter demographics

Political parties are not static entities; they evolve to survive. One of the most striking ways they adapt is by shifting their core beliefs to align with emerging voter demographics. Consider the British Labour Party, which transitioned from a socialist platform in the mid-20th century to a centrist "Third Way" under Tony Blair in the 1990s. This ideological pivot targeted middle-class voters disillusioned with traditional left-wing policies, demonstrating how parties recalibrate their principles to capture new constituencies. Such shifts are not merely tactical but often redefine a party’s identity for decades.

To execute an ideological shift effectively, parties must first identify the values and priorities of their target demographic. For instance, the Republican Party in the U.S. began emphasizing cultural conservatism and religious values in the 1980s to appeal to suburban and rural voters. This required a deliberate reorientation away from its earlier focus on fiscal conservatism alone. Practical steps include conducting voter surveys, analyzing demographic trends, and appointing strategists who understand the new audience. However, caution is necessary: abrupt changes risk alienating the party’s traditional base, as seen in the backlash against the Democratic Party’s shift toward progressive policies in recent years.

A persuasive case for ideological shifts lies in their ability to rejuvenate a party’s relevance. The Green parties across Europe, for example, have broadened their focus from environmentalism to include social justice and economic equality, attracting younger, urban voters. This expansion of core beliefs transforms single-issue parties into comprehensive political movements. Yet, such shifts must be authentic; voters can detect insincerity, as evidenced by the failure of some conservative parties to convincingly adopt green policies. Authenticity requires not just policy changes but also leadership that embodies the new ideals.

Comparatively, ideological shifts in multiparty systems differ from those in two-party systems. In India, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) shifted from a Hindu nationalist platform to a more inclusive development-focused agenda to appeal to a broader electorate. This contrasts with the U.S., where the two-party system limits the scope of such shifts due to the need to maintain a broad coalition. In multiparty systems, smaller parties can afford more radical changes, while dominant parties in two-party systems must balance appealing to new voters with retaining their core base.

Descriptively, an ideological shift is akin to a ship changing course—slow, deliberate, and requiring constant adjustment. Take the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), which moved from a Marxist-influenced platform to a pro-market, welfare-state model. This transformation involved not just policy revisions but also a cultural shift within the party, from union-centric activism to a broader focus on governance. Such changes are not without internal strife, as factions resist abandoning long-held beliefs. Yet, when successful, they redefine a party’s role in the political landscape, ensuring its survival in a changing world.

Iowa Court of Appeals: Political Party Affiliation Explained

You may want to see also

Leadership Changes: Impact of new leaders on party direction and voter perception

Leadership changes within political parties often serve as pivotal moments that can redefine a party's trajectory and reshape its public image. When a new leader takes the helm, they bring with them a unique set of ideologies, communication styles, and strategic priorities. These shifts are not merely internal adjustments; they ripple outward, influencing voter perception and altering the party's standing in the political landscape. For instance, the election of Jeremy Corbyn as the leader of the UK Labour Party in 2015 marked a sharp leftward turn, polarizing both the party and its electorate. Such changes underscore the profound impact leadership transitions can have on a party's identity and electoral fortunes.

To understand this dynamic, consider the mechanics of leadership change. A new leader typically inherits a party with established policies, factions, and voter bases. Their ability to navigate these complexities determines whether the party consolidates its position or fractures. For example, when Justin Trudeau became leader of Canada’s Liberal Party in 2013, he revitalized the party by emphasizing progressive values and youthful energy, which resonated with younger voters and led to a landslide victory in 2015. Conversely, a misalignment between a leader’s vision and the party’s traditional base can alienate core supporters. Practical tip: Parties should conduct internal surveys to gauge member sentiment before and after a leadership change to ensure alignment and mitigate potential backlash.

Voter perception is equally critical, as it often hinges on the leader’s ability to communicate their vision effectively. A leader’s charisma, policy clarity, and responsiveness to public concerns can either galvanize support or erode trust. Take the case of Jacinda Ardern in New Zealand, whose empathetic leadership during crises like the Christchurch mosque shootings and the COVID-19 pandemic significantly boosted her party’s popularity. In contrast, leaders who fail to connect with voters on emotional or practical levels risk being perceived as out of touch. Dosage value: Leaders should allocate at least 30% of their public engagements to grassroots interactions, such as town halls or social media Q&A sessions, to maintain a pulse on voter sentiment.

The impact of leadership changes also varies across age categories. Younger voters, for instance, tend to prioritize leaders who champion issues like climate change and social justice, while older demographics may focus on economic stability and traditional values. A leader’s ability to balance these competing priorities can determine the party’s appeal across generations. For example, Germany’s Green Party, under the co-leadership of Annalena Baerbock and Robert Habeck, has successfully bridged this gap by combining environmental policies with pragmatic economic strategies, attracting both young activists and older moderates. Caution: Overemphasis on one demographic at the expense of another can lead to voter fragmentation, so leaders must adopt inclusive messaging.

In conclusion, leadership changes are high-stakes moments that can either propel a party forward or plunge it into turmoil. The key lies in a leader’s ability to harmonize their vision with the party’s existing framework while adapting to the evolving demands of the electorate. Parties must approach these transitions strategically, leveraging data-driven insights and inclusive communication to ensure a smooth realignment. By doing so, they can not only survive but thrive in the face of leadership shifts, turning potential challenges into opportunities for growth and renewal.

When Ballers Became Political: The Evolution of Athlete Activism

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$17.96 $35

Electoral Strategies: Tactics like gerrymandering or coalition-building that influence party dominance

Political parties often swap dominance through strategic manipulation of electoral systems, leveraging tactics like gerrymandering and coalition-building to reshape the political landscape. Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing district boundaries to favor one party, is a blunt instrument that can lock in advantages for decades. For instance, in 2012, Republicans in Pennsylvania redrew congressional maps to secure 13 out of 18 seats despite winning only 49% of the statewide vote. This tactic exploits the principle of "wasted votes," concentrating opposition supporters in a few districts while diluting their influence elsewhere. However, its effectiveness hinges on controlling redistricting processes, often tied to state legislative majorities.

Coalition-building, by contrast, is a dynamic strategy that relies on forging alliances across diverse voter groups. Barack Obama’s 2008 and 2012 victories exemplified this approach, uniting young voters, minorities, and urban professionals under a shared vision. Such coalitions require careful messaging and policy compromises, as seen in the Democratic Party’s balancing act between progressive and moderate factions. Unlike gerrymandering, coalition-building is adaptable but fragile, vulnerable to shifts in public sentiment or the emergence of wedge issues. For example, the 2016 election highlighted how a coalition can fracture when economic anxieties or cultural divides are exploited.

While gerrymandering offers immediate structural advantages, it risks backlash if perceived as undemocratic. Legal challenges, such as those in North Carolina and Ohio, have increasingly invalidated extreme gerrymanders, underscoring the tactic’s limitations. Coalition-building, though labor-intensive, fosters broader legitimacy and resilience. Parties must weigh these trade-offs: gerrymandering provides a short-term edge but may alienate voters, while coalition-building demands sustained effort but can yield long-term dominance.

Practical tips for parties include monitoring census data to anticipate redistricting opportunities and investing in voter analytics to identify potential coalition partners. For instance, Democrats in Georgia leveraged demographic shifts and grassroots organizing to flip the state in 2020, combining both strategies. Ultimately, the choice between gerrymandering and coalition-building reflects a party’s risk tolerance and ideological flexibility. Mastery of these tactics can determine not just electoral outcomes but the very balance of power in a political system.

Understanding Political Stakeholders: Key Players Shaping Policies and Decisions

You may want to see also

Social Movements: Role of grassroots movements in pushing parties to adopt new policies

Grassroots movements have historically served as catalysts for policy shifts within political parties, often forcing them to adapt to emerging societal demands. Consider the Civil Rights Movement in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s. Through sustained protests, boycotts, and civil disobedience, activists pressured both Democratic and Republican parties to address racial inequality. This culminated in landmark legislation like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The movement’s success demonstrates how sustained, organized action at the local level can compel parties to adopt policies they might have previously resisted.

To replicate this impact, grassroots organizers must focus on three key strategies: coalition-building, narrative framing, and direct engagement with policymakers. First, coalitions amplify the movement’s reach and legitimacy. For instance, the LGBTQ+ rights movement gained momentum by uniting diverse groups—religious organizations, labor unions, and youth activists—under a common cause. Second, framing the issue in a way that resonates with a broad audience is crucial. The climate justice movement, for example, shifted from emphasizing environmental preservation to highlighting economic opportunities in green jobs, appealing to both environmentalists and workers. Lastly, direct engagement with local and national representatives ensures that demands are heard and cannot be ignored.

However, grassroots movements must navigate challenges to maintain their influence. One risk is co-optation by political parties, which may adopt watered-down versions of demanded policies to appease activists without addressing root issues. The #MeToo movement, while raising global awareness about sexual harassment, saw limited legislative action in many countries. To counter this, movements must remain independent, continuously pressure parties, and hold them accountable for promises made. Another challenge is internal fragmentation, as seen in the Occupy Wall Street movement, where a lack of clear leadership and goals hindered long-term impact.

A comparative analysis reveals that movements in proportional representation systems, like those in Scandinavia, often achieve policy victories more swiftly than those in winner-takes-all systems. In Sweden, grassroots campaigns for gender equality led to comprehensive parental leave policies, supported by multiple parties. In contrast, the U.S. reproductive rights movement has faced greater obstacles due to partisan polarization. This suggests that structural factors, such as electoral systems, play a role in determining a movement’s success, but they do not negate the power of persistent grassroots organizing.

In conclusion, grassroots movements are indispensable in pushing political parties to adopt new policies, but their effectiveness depends on strategic organizing, resilience, and an understanding of the political landscape. By learning from historical successes and failures, today’s activists can maximize their impact, ensuring that parties not only hear their demands but act on them. Practical tips include leveraging social media for mobilization, conducting voter education campaigns, and building alliances with international movements to amplify global pressure. The key takeaway is clear: while parties may swap positions, it is often the relentless energy of grassroots movements that drives such shifts.

Understanding Recusal in Politics: Ethics, Impartiality, and Conflict Avoidance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

When political parties "swap," it typically refers to a shift in their traditional positions or ideologies, often resulting in one party adopting policies or stances historically associated with the other. This can occur due to changing voter demographics, leadership changes, or strategic realignment.

The frequency of ideological swaps varies by country and political context. In some cases, it happens gradually over decades, while in others, it can occur more rapidly due to significant events like economic crises, social movements, or shifts in global politics.

One notable example is the Democratic and Republican parties in the U.S. during the 20th century. The Democrats, once associated with segregationist policies in the South, shifted to champion civil rights, while the Republicans, historically the party of Lincoln and abolition, became dominant in the South by appealing to conservative voters.

Parties often swap positions to adapt to changing voter preferences, capitalize on new political opportunities, or respond to societal shifts. Leadership changes, electoral strategies, and the rise of new issues (e.g., climate change or globalization) can also trigger such shifts.