The formation of political parties in the United States traces its roots to the early years of the nation's independence, emerging from the ideological divisions among the Founding Fathers. Initially, the Constitution did not envision a party system, but the differing views on the role of government, economic policies, and foreign relations led to the creation of the first political factions. The Federalist Party, led by Alexander Hamilton, advocated for a strong central government and industrialization, while the Democratic-Republican Party, spearheaded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, championed states' rights, agrarian interests, and limited federal power. These early divisions laid the groundwork for the two-party system that has dominated American politics, evolving over time into the modern Democratic and Republican Parties. The development of political parties was further shaped by issues such as slavery, westward expansion, and economic reforms, reflecting the dynamic and often contentious nature of American democracy.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Historical Context | Political parties in the U.S. emerged in the late 18th century during the ratification of the Constitution. The first two major parties were the Federalists (led by Alexander Hamilton) and the Democratic-Republicans (led by Thomas Jefferson). |

| Ideological Divisions | Parties form around differing ideologies, such as federal power vs. states' rights, economic policies, and social issues. Modern parties reflect these divisions, with Democrats generally favoring progressive policies and Republicans advocating conservative principles. |

| Electoral Needs | Parties organize to mobilize voters, raise funds, and coordinate campaigns. They serve as vehicles for candidates to gain political office. |

| Leadership and Factions | Parties often form around influential leaders or factions. For example, the Republican Party solidified under Abraham Lincoln, while the modern Democratic Party was shaped by figures like Franklin D. Roosevelt. |

| Geographic and Demographic Bases | Parties develop regional and demographic strongholds. Historically, the Democratic Party dominated the South, while the Republican Party was strong in the North. Today, Democrats are stronger in urban areas, and Republicans in rural regions. |

| Third-Party Challenges | Third parties occasionally emerge to challenge the two-party system, though they rarely gain significant traction due to structural barriers like winner-take-all elections and campaign finance laws. |

| Party Platforms | Parties adopt formal platforms outlining their policy positions during national conventions. These platforms evolve over time to reflect changing societal priorities. |

| Organizational Structure | Parties have national, state, and local committees that coordinate activities, fundraise, and recruit candidates. The Democratic National Committee (DNC) and Republican National Committee (RNC) are key examples. |

| Primary Systems | Parties use primaries and caucuses to nominate candidates for general elections. These systems have evolved to increase voter participation and transparency. |

| Media and Communication | Parties leverage media and technology to shape public opinion, disseminate messages, and mobilize supporters. Social media has become a critical tool in modern party formation and outreach. |

| Coalition Building | Parties form coalitions of diverse interest groups to broaden their appeal. For example, the Democratic Party includes labor unions, minority groups, and environmentalists, while the Republican Party aligns with business interests and religious conservatives. |

| Legal and Institutional Framework | The U.S. electoral system, including ballot access laws and campaign finance regulations, influences party formation and sustainability. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Early Factions: Jeffersonian Republicans vs. Federalists, emerging from debates over Constitution and government role

- Second Party System: Democrats and Whigs rise, shaped by Jacksonian democracy and economic policies

- Civil War Impact: Republican Party forms, replacing Whigs, over slavery and national unity issues

- Progressive Era: Third parties like Populists and Progressives push reforms, influencing major parties

- Modern Two-Party System: Post-1960s realignment solidifies Democrats and Republicans as dominant forces

Early Factions: Jeffersonian Republicans vs. Federalists, emerging from debates over Constitution and government role

The United States’ first political factions, the Jeffersonian Republicans and the Federalists, emerged from fiery debates over the Constitution’s interpretation and the federal government’s role. These early divisions weren’t just ideological spats—they shaped the nation’s political DNA. At the heart of the conflict was a fundamental question: Should the federal government be strong and centralized, or limited and deferential to states’ rights? The Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, championed a robust national government, while Thomas Jefferson’s Republicans advocated for agrarian interests and local control. This clash wasn’t merely academic; it influenced policies, alliances, and the very structure of American governance.

Consider the Federalist vision: They pushed for a national bank, tariffs, and infrastructure projects, arguing these measures would stabilize the economy and assert federal authority. Hamilton’s *Report on Manufactures* (1791) exemplified this approach, proposing subsidies for industry and manufacturing. In contrast, Jeffersonian Republicans viewed such policies as elitist and dangerous, favoring a decentralized government that protected individual liberties and agrarian life. Their opposition to the national bank, for instance, wasn’t just economic—it was a philosophical stand against what they saw as federal overreach. These competing priorities created a political fault line that defined early American politics.

The debates weren’t confined to policy; they spilled into the realm of constitutional interpretation. Federalists embraced a loose construction of the Constitution, arguing that the "necessary and proper" clause granted Congress broad powers. Jeffersonians, however, adhered to strict constructionism, insisting the federal government could only act where explicitly authorized. This divide was evident in the Whiskey Rebellion (1794), where Federalists supported using federal force to suppress tax protests, while Jeffersonians criticized the move as an abuse of power. Such incidents highlighted the factions’ differing views on the balance between federal authority and state sovereignty.

Practical implications of this divide are still felt today. For instance, the Federalist emphasis on a strong central government laid the groundwork for modern federal agencies, while Jeffersonian ideals continue to fuel debates over states’ rights and limited government. To understand this dynamic, examine how contemporary issues like healthcare or environmental regulation often pit centralized solutions against local control. The early factions’ debates weren’t just historical footnotes—they were the blueprint for ongoing political battles.

In navigating this history, it’s instructive to analyze primary sources like Jefferson’s *Kentucky Resolutions* (1798) or Federalist Papers Nos. 10 and 51. These documents reveal the factions’ core arguments and strategies, offering insights into how political parties form and evolve. For educators or students, pairing these texts with case studies of modern political disputes can illustrate the enduring relevance of these early debates. The takeaway? The Jeffersonian-Federalist rivalry wasn’t just about the 18th century—it’s a lens for understanding the tensions that continue to shape American politics.

Can Foreign Political Parties Register and Operate Legally in the USA?

You may want to see also

Second Party System: Democrats and Whigs rise, shaped by Jacksonian democracy and economic policies

The Second Party System, emerging in the 1830s, marked a transformative era in American politics, defined by the rise of the Democratic Party and the Whig Party. This period was deeply shaped by the principles of Jacksonian democracy, which emphasized the sovereignty of the "common man" and a skepticism of centralized power. Andrew Jackson’s presidency (1829–1837) became the ideological cornerstone for the Democrats, who championed states’ rights, limited federal intervention, and the expansion of suffrage to white male citizens. In contrast, the Whigs, led by figures like Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, advocated for a stronger federal government, internal improvements, and a national bank to foster economic growth. This ideological divide set the stage for a decade of intense political competition.

To understand the Whigs’ rise, consider their economic policies as a direct response to Jacksonian populism. While Democrats opposed the Second Bank of the United States and favored an agrarian economy, Whigs pushed for industrialization, tariffs to protect American manufacturers, and federally funded infrastructure projects like roads and canals. This economic vision appealed to urban merchants, industrialists, and those in the North and West who stood to benefit from modernization. For instance, Clay’s "American System" became the Whigs’ policy blueprint, aiming to unite diverse economic interests under a national framework. Practically, this meant advocating for tariffs like the Tariff of 1842, which protected domestic industries but alienated Southern planters who relied on international trade.

The Democrats, meanwhile, capitalized on Jackson’s charisma and their appeal to the "common man." They framed their opposition to the national bank and federal projects as a defense of individual liberty against elite corruption. Jackson’s veto of the Maysville Road Bill in 1830 exemplified this stance, rejecting federal funding for local projects as unconstitutional. This populist rhetoric resonated with small farmers, laborers, and those wary of centralized power. However, the Democrats’ policies also had practical consequences, such as the Panic of 1837, which critics blamed on Jackson’s dismantling of the national bank and his speculative land policies.

A comparative analysis reveals how these parties’ strategies reflected broader societal shifts. The Democrats’ grassroots appeal and emphasis on states’ rights aligned with the expansion of democracy, while the Whigs’ focus on economic development catered to emerging industrial interests. For example, the Democrats’ support for the independent treasury system in the 1840s aimed to curb financial speculation, while the Whigs continued to push for a national bank. These differences were not merely ideological but had tangible impacts on voters’ lives, from the availability of credit to the pace of industrialization.

In conclusion, the Second Party System was a crucible for modern American politics, with Democrats and Whigs embodying competing visions of governance and economic policy. Jacksonian democracy fueled the Democrats’ populist agenda, while the Whigs’ emphasis on federal activism laid the groundwork for future Republican policies. By examining their rise, we see how political parties are not just vehicles for power but reflections of societal values and economic realities. For those studying political history, this era offers a practical lesson: parties succeed by aligning their ideologies with the material interests of their constituents, a principle as relevant today as it was in the 1830s.

Did George Washington Warn Against Political Parties?

You may want to see also

Civil War Impact: Republican Party forms, replacing Whigs, over slavery and national unity issues

The collapse of the Whig Party in the 1850s created a political vacuum that the newly formed Republican Party swiftly filled, driven by the escalating tensions over slavery and national unity. The Whigs, once a dominant force, fractured over their inability to reconcile pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise, became a tipping point. Anti-slavery Whigs, along with Free Soilers and disaffected Democrats, coalesced to form the Republican Party, explicitly opposing the expansion of slavery into new territories. This realignment was not merely a party shift but a reflection of the deepening ideological divide that would soon plunge the nation into civil war.

To understand the Republican Party’s rise, consider its strategic focus on two core issues: preventing the spread of slavery and preserving national unity. Unlike the Whigs, who often equivocated on slavery, the Republicans adopted a clear stance, appealing to Northern voters who feared the economic and moral implications of slavery’s expansion. Their platform resonated with a growing coalition of abolitionists, industrialists, and farmers, who saw the party as a bulwark against Southern political dominance. For instance, the 1856 Republican National Convention in Philadelphia highlighted their commitment to these principles, even though they lost the presidential election that year. This early defeat laid the groundwork for their eventual victory in 1860, when Abraham Lincoln’s election precipitated Southern secession.

The formation of the Republican Party illustrates how external crises can catalyze political realignment. The Whigs’ dissolution was not just a failure of leadership but a symptom of the broader societal rift over slavery. The Republicans capitalized on this by framing their agenda as a defense of national integrity and economic progress. Practical lessons from this period include the importance of clarity in political messaging and the ability to mobilize diverse constituencies around a unifying cause. For modern political organizers, this underscores the value of identifying and addressing the root causes of division rather than merely reacting to them.

Comparing the Whigs’ downfall to the Republicans’ ascent reveals the critical role of adaptability in political survival. While the Whigs struggled to navigate the slavery issue, the Republicans embraced it as their defining mission. This contrast highlights a timeless political truth: parties that fail to evolve in response to shifting societal values risk obsolescence. For those studying party formation, the Republican Party’s emergence offers a case study in how to transform ideological coherence into electoral success. By focusing on actionable policies and building broad-based coalitions, they not only replaced the Whigs but also reshaped American politics for decades to come.

Finally, the Republican Party’s formation serves as a cautionary tale about the consequences of ignoring deep-seated national divisions. Their rise was inseparable from the tensions that ultimately led to the Civil War, demonstrating how political parties can both reflect and exacerbate societal conflicts. For contemporary policymakers, this history underscores the need to address divisive issues proactively rather than allowing them to fester. The Republicans’ success was not just in winning elections but in articulating a vision of national unity that, despite the war, laid the foundation for post-war reconstruction. This legacy reminds us that the stakes of political realignment extend far beyond party lines, shaping the course of a nation’s future.

Gracefully Declining Office Birthday Treats: Polite Strategies for Saying No

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$11.99 $16.95

$28.31 $42

Progressive Era: Third parties like Populists and Progressives push reforms, influencing major parties

The late 19th and early 20th centuries marked a transformative period in American politics known as the Progressive Era, during which third parties like the Populists and Progressives emerged as catalysts for reform. These parties, though often marginalized in electoral outcomes, wielded disproportionate influence by pushing issues like antitrust legislation, labor rights, and direct democracy into the national spotlight. Their relentless advocacy forced the major parties—Democrats and Republicans—to adopt or adapt these ideas to remain relevant, effectively reshaping the political landscape.

Consider the Populist Party, which arose in the 1890s as a voice for struggling farmers and rural workers. Their platform, encapsulated in the Omaha Platform of 1892, demanded radical changes such as the nationalization of railroads, a graduated income tax, and the direct election of senators. While the Populists faded after the 1896 election, their ideas lived on. For instance, the Seventeenth Amendment, ratified in 1913, established the direct election of senators—a direct legacy of Populist agitation. This example illustrates how third parties can drive systemic change even when they fail to win elections.

The Progressive Party, founded in 1912 by Theodore Roosevelt, offers another compelling case study. Frustrated by the conservatism of the Republican Party, Roosevelt championed a platform of trust-busting, women’s suffrage, and workplace safety regulations. Though he lost the presidency, his campaign compelled both major parties to embrace progressive reforms. Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic victor, adopted many of Roosevelt’s ideas, including the Federal Reserve Act and the Clayton Antitrust Act. This demonstrates how third-party challenges can force major parties to evolve, often co-opting their agendas to maintain electoral viability.

To understand the mechanics of this influence, consider the role of public pressure. Third parties thrive by mobilizing grassroots support around specific issues, creating a groundswell of demand that major parties cannot ignore. For example, the Progressive Party’s focus on corruption and corporate power resonated with a broad swath of voters, compelling Democrats and Republicans to address these concerns. Practical tip: When advocating for reform, align with third-party movements to amplify your message and increase the likelihood of major-party adoption.

In conclusion, the Progressive Era underscores the critical role of third parties in driving political change. By championing bold reforms and mobilizing public support, the Populists and Progressives forced the major parties to adapt, leaving a lasting imprint on American policy. This dynamic remains relevant today, as contemporary third parties continue to push issues like climate change and campaign finance reform into the mainstream. For those seeking to influence politics, the lesson is clear: third parties may not always win elections, but they can win the debate—and that’s often enough to change the course of history.

Why 'Midget' is Offensive: Embracing Respectful Language for Little People

You may want to see also

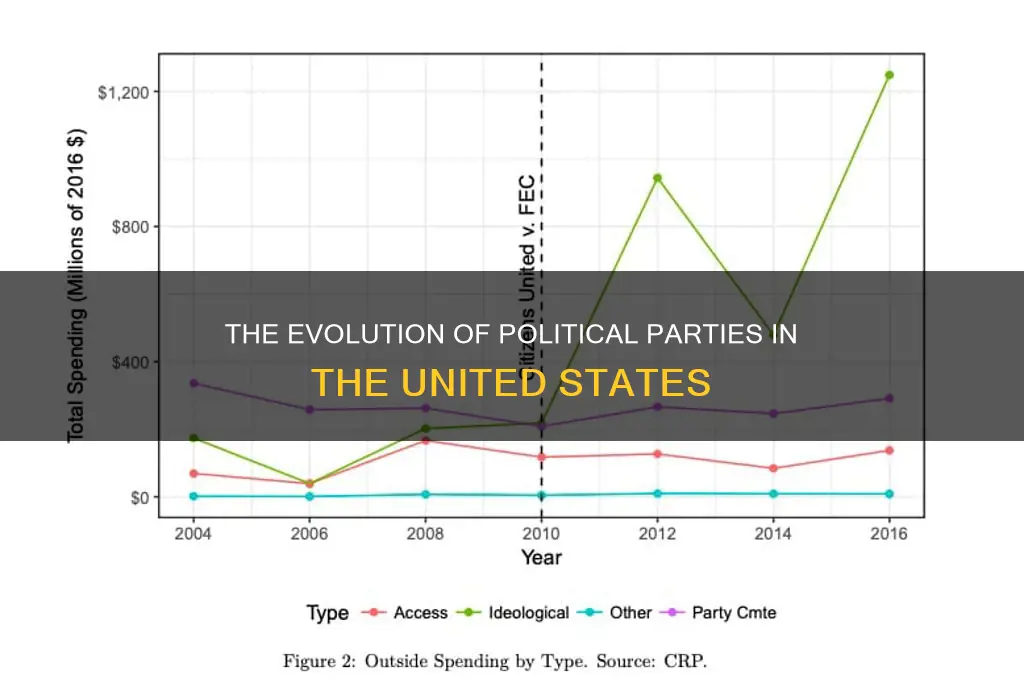

Modern Two-Party System: Post-1960s realignment solidifies Democrats and Republicans as dominant forces

The 1960s marked a seismic shift in American politics, reshaping the ideological and geographic foundations of the Democratic and Republican parties. This era, characterized by civil rights movements, cultural upheavals, and economic transformations, forced both parties to redefine their identities. Democrats, once a coalition of Southern conservatives and Northern liberals, increasingly embraced civil rights and progressive policies, alienating their traditional Southern base. Republicans, under the leadership of figures like Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon, capitalized on this shift by adopting the "Southern Strategy," appealing to conservative Southern voters disillusioned with the Democratic Party. This realignment solidified the modern two-party system, with Democrats becoming the party of urban, minority, and progressive voters, and Republicans attracting rural, white, and conservative supporters.

Consider the 1964 presidential election as a turning point. Barry Goldwater’s staunch opposition to the Civil Rights Act signaled the GOP’s pivot toward states’ rights and conservative values, while Lyndon B. Johnson’s landslide victory masked the growing fracture within the Democratic Party. By the 1970s, this fracture became a chasm, as Southern Democrats began migrating to the Republican Party. The 1980 election of Ronald Reagan further cemented this trend, as his appeal to economic conservatism and social traditionalism attracted both Northern blue-collar workers and Southern conservatives. This period demonstrated how demographic and ideological shifts could fundamentally alter party coalitions, leaving Democrats and Republicans as the dominant forces in American politics.

To understand the post-1960s realignment, examine the role of key issues like civil rights, abortion, and economic policy. The Democratic Party’s embrace of civil rights alienated conservative Southern voters, while its support for reproductive rights and social welfare programs drew in urban and minority voters. Conversely, the Republican Party’s focus on law and order, anti-communism, and fiscal conservatism resonated with suburban and rural voters. Practical tip: Analyze voting patterns in states like Texas and Georgia, which shifted from reliably Democratic to solidly Republican over this period, to see how these issues played out geographically.

A comparative analysis reveals the stark contrast between the pre- and post-1960s party systems. Before the 1960s, the Democratic Party dominated the South, while the Republican Party held sway in the Northeast. By the 1990s, this alignment had flipped, with Republicans dominating the South and Democrats gaining ground in the Northeast and West Coast. This transformation underscores the fluidity of party identities and the enduring impact of realignment. Takeaway: The post-1960s era illustrates how parties can reinvent themselves by adapting to changing societal values and demographic trends, ensuring their dominance in a two-party system.

Finally, the modern two-party system is not without its challenges. The polarization that emerged from this realignment has deepened in recent decades, with both parties becoming more ideologically homogeneous and less willing to compromise. This dynamic has led to legislative gridlock and heightened political tensions. However, the system’s resilience lies in its ability to absorb and reflect societal changes, ensuring that Democrats and Republicans remain the primary vehicles for political expression in the U.S. Practical advice: To navigate this polarized landscape, voters should focus on understanding the historical roots of party realignment and how it shapes current political discourse, enabling more informed and nuanced engagement.

Exploring T.D. Evans' Political Party Affiliation: Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The first political parties in the U.S. emerged during George Washington's presidency in the 1790s. The Federalist Party, led by Alexander Hamilton, supported a strong central government and industrialization, while the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson, advocated for states' rights and agrarian interests.

The two-party system, dominated by Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, shaped early American politics by providing competing visions for the nation's future. It fostered debates on issues like government power, economic policies, and individual rights, laying the foundation for modern political discourse.

Political parties have evolved significantly since the 19th century, with the Democratic and Republican Parties replacing the earlier Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. Issues like slavery, industrialization, civil rights, and economic policies have reshaped party platforms, leading to the modern alignment of conservative and liberal ideologies.

New political parties often form due to dissatisfaction with the existing two-party system, emerging social or economic issues, or the desire to represent specific ideologies or demographics. Examples include the Progressive Party, Libertarian Party, and Green Party, which arose to address perceived gaps in mainstream politics.