The election of political parties in France is a complex and multifaceted process that reflects the country's rich political history and diverse ideological landscape. Governed by a semi-presidential system, France's political structure combines elements of both parliamentary and presidential systems, with the President and the National Assembly playing pivotal roles. Political parties in France range from traditional center-right and center-left groups, such as The Republicans (LR) and the Socialist Party (PS), to newer movements like La République En Marche! (LREM), founded by President Emmanuel Macron, and more radical parties on both the left, such as La France Insoumise (LFI), and the right, like the National Rally (RN). Elections are conducted through a two-round voting system for presidential elections and a mix of proportional and majority systems for legislative elections, ensuring representation across various political spectra. This intricate electoral framework highlights the dynamic interplay between parties, voter preferences, and institutional mechanisms in shaping France's political governance.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Electoral System | Two-round (runoff) system for presidential elections; proportional and majority systems for legislative elections. |

| Presidential Election | Direct election; candidate must secure a majority (50%+1) in the first round or proceed to a runoff between the top two candidates. |

| Legislative Election | Mixed system: 85% of seats allocated via two-round majority voting in single-member districts; 15% via proportional representation. |

| Term Length | President: 5 years (renewable once); National Assembly: 5 years. |

| Major Political Parties | Renaissance (centrist), The Republicans (center-right), National Rally (far-right), Socialist Party (center-left), La France Insoumise (left-wing). |

| Voting Age | 18 years old. |

| Last Presidential Election (2022) | Emmanuel Macron (Renaissance) won reelection with 58.55% in the runoff against Marine Le Pen (National Rally). |

| Last Legislative Election (2022) | Resulted in a hung parliament; Macron’s coalition (Ensemble!) secured a plurality but lost absolute majority. |

| Key Issues in Elections | Economy, immigration, climate change, healthcare, and European integration. |

| Campaign Financing | Strict regulations; public funding based on election results and private donations capped. |

| Role of Media | Significant influence; televised debates and social media play crucial roles in campaigns. |

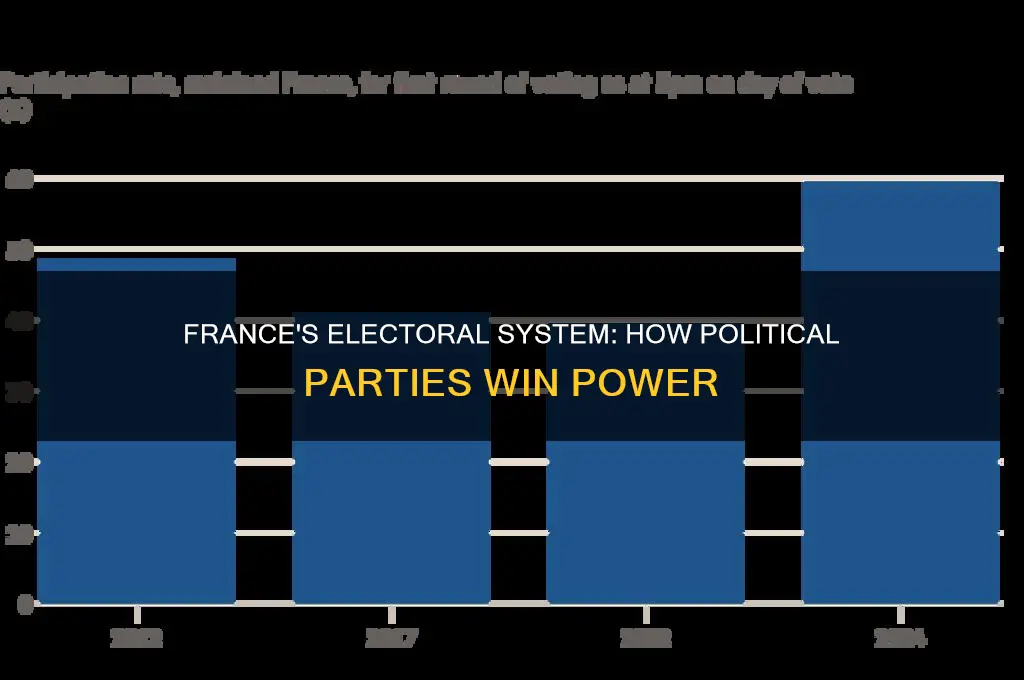

| Voter Turnout (2022) | Presidential runoff: 71.99%; Legislative elections: 47.5% (first round), 46.2% (second round). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Electoral System: France uses a two-round voting system for presidential and legislative elections

- Party Funding: Public and private funding rules regulate political party finances and campaign spending

- Campaign Strategies: Parties leverage media, rallies, and digital platforms to mobilize voters and convey messages

- Coalitions and Alliances: Parties often form alliances to secure majority support in legislative elections

- Voter Demographics: Age, region, and socioeconomic factors significantly influence voting patterns and party success

Electoral System: France uses a two-round voting system for presidential and legislative elections

France's electoral system is a masterclass in ensuring majority rule while fostering coalition-building. The two-round voting system, used for both presidential and legislative elections, is a cornerstone of this approach. In the first round, candidates from various parties compete. If no candidate secures an absolute majority (over 50%), a second round is triggered, featuring only the top two contenders. This runoff guarantees the eventual winner has the support of a majority of voters, a stark contrast to systems where a plurality can suffice.

Imagine a presidential race with five candidates. In the first round, Candidate A receives 35%, B gets 28%, C 20%, D 12%, and E 5%. Since no one reaches 50%, A and B advance to the second round. Here, voters who supported C, D, or E must strategically choose between the remaining two, potentially leading to alliances and compromises.

This system encourages strategic voting and fosters a more nuanced political landscape. Smaller parties, while unlikely to win outright, can wield significant influence by endorsing a major candidate in the second round. This dynamic often leads to pre-election agreements and post-election coalitions, shaping the political agenda. For instance, a green party might back a center-left candidate in exchange for policy concessions on environmental issues.

This two-round system isn't without its critics. Some argue it can lead to tactical voting, where voters choose not based on their true preference but to prevent a less desirable candidate from winning. Additionally, the system can disadvantage smaller parties that consistently fail to reach the second round, potentially limiting political diversity.

Despite these criticisms, France's two-round system has proven effective in producing stable governments and encouraging political compromise. It's a system that rewards both popular appeal and the ability to build bridges across the political spectrum, reflecting the complexities of modern democracies. Understanding this mechanism is crucial for anyone seeking to comprehend the intricacies of French politics and the rise and fall of its political parties.

Elise Stefanik's Rise: Unpacking Her Role in American Politics

You may want to see also

Party Funding: Public and private funding rules regulate political party finances and campaign spending

In France, political parties rely on a dual funding system that balances public subsidies with private contributions, a framework designed to ensure transparency and fairness in electoral processes. Public funding is allocated based on a party’s electoral performance, specifically the number of votes obtained in legislative elections. For instance, parties receive approximately €1.42 per vote in the first round of legislative elections, provided they surpass a 1% vote threshold in at least 50 constituencies. This mechanism incentivizes parties to maintain broad electoral appeal while reducing dependency on private donors.

Private funding, though permitted, is tightly regulated to prevent undue influence. Individuals can donate up to €7,500 annually to a single party, with all contributions over €150 requiring a written receipt. Corporate donations are entirely prohibited, a rule implemented to curb potential corruption and ensure that parties remain accountable to citizens rather than special interests. These restrictions are enforced by the *Commission nationale des comptes de campagne et des financements politiques* (CNCCFP), which audits party finances and imposes penalties for violations, including fines or funding reductions.

The interplay between public and private funding reflects France’s commitment to democratic equity. Public subsidies account for roughly 60% of party income, fostering a level playing field for smaller parties that might struggle to attract private donors. However, this system is not without criticism. Some argue that public funding perpetuates the dominance of established parties, as smaller parties must first achieve electoral success to qualify for subsidies. Others contend that private funding limits stifle grassroots movements, making it harder for new parties to emerge.

Practical implications of these rules are evident in campaign spending limits, which are capped based on election type and round. For presidential elections, candidates advancing to the second round can spend up to €22.5 million, while first-round candidates are limited to €16.8 million. Exceeding these limits results in reimbursement denial and potential legal consequences. This structure ensures that financial resources do not distort electoral outcomes, though it places significant administrative burdens on parties to track and report expenditures meticulously.

Ultimately, France’s party funding rules serve as a model for balancing financial sustainability with democratic integrity. While public subsidies promote inclusivity, private funding restrictions mitigate external influence. For parties navigating this system, the key lies in strategic planning: maximizing public funding through electoral performance while cultivating a broad donor base within legal limits. This dual approach not only sustains party operations but also reinforces public trust in the political process.

Understanding Coherent Political Parties: Unity, Ideology, and Effective Governance

You may want to see also

Campaign Strategies: Parties leverage media, rallies, and digital platforms to mobilize voters and convey messages

In France, political parties wield a multifaceted arsenal of campaign strategies to sway public opinion and secure electoral victories. Central to their efforts is the strategic use of media, rallies, and digital platforms, each serving distinct yet complementary roles in mobilizing voters and conveying messages. Media, particularly television, remains a cornerstone of French political campaigns, offering parties a broad reach and the ability to frame narratives through debates, interviews, and advertisements. For instance, presidential candidates often participate in televised debates, such as the iconic *débat de l'entre-deux-tours*, which can significantly influence voter perceptions in the final stretch of an election.

Rallies, on the other hand, provide a more visceral, emotional connection between candidates and their supporters. These events are carefully choreographed to evoke unity and enthusiasm, often featuring speeches, chants, and symbolic imagery. The 2017 campaign of Emmanuel Macron, for example, leveraged large-scale rallies to project an image of momentum and grassroots support, which proved crucial in his eventual victory. However, organizing rallies requires meticulous planning, from venue selection to crowd management, and parties must balance their impact with the risk of logistical mishaps or low turnout.

Digital platforms have emerged as a game-changer in French political campaigns, offering unprecedented opportunities for targeted messaging and voter engagement. Social media, in particular, allows parties to bypass traditional media gatekeepers and communicate directly with voters. During the 2022 presidential election, candidates like Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon utilized platforms like Twitter and Facebook to share policy proposals, respond to critics, and mobilize their bases. Digital campaigns also incorporate data analytics to tailor messages to specific demographics, a tactic increasingly employed by parties across the political spectrum.

Yet, the integration of these strategies is not without challenges. Media campaigns can backfire if messages are perceived as insincere or contradictory, while over-reliance on digital platforms risks alienating older voters who are less active online. Rallies, while powerful, can be costly and may fail to translate enthusiasm into actual votes. To maximize effectiveness, parties must adopt a holistic approach, synchronizing their efforts across media, rallies, and digital platforms. For instance, a well-timed rally can generate buzz that is amplified through social media, while televised appearances can reinforce messages disseminated online.

In practice, successful campaigns require a delicate balance of creativity, discipline, and adaptability. Parties must monitor public sentiment in real time, adjusting their strategies to address emerging issues or counter opponents' moves. For example, during the 2017 legislative elections, La République En Marche! (LREM) used a combination of targeted digital ads and local rallies to secure a parliamentary majority, demonstrating the power of integrated campaign strategies. Ultimately, the key to victory lies in understanding the unique strengths of each platform and leveraging them to create a cohesive, compelling narrative that resonates with voters.

Remembering a Political Titan: Who Passed Away Recently?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Coalitions and Alliances: Parties often form alliances to secure majority support in legislative elections

In France's semi-presidential system, legislative elections often hinge on the ability of political parties to form strategic alliances. The National Assembly, with its 577 seats, requires a majority of 289 to pass legislation effectively. Given the fragmentation of the political landscape, no single party typically secures this threshold alone. This reality necessitates coalitions, where parties pool their votes to achieve a governing majority. For instance, in the 2022 legislative elections, President Macron’s Ensemble coalition, comprising Renaissance, the Democratic Movement, and Horizons, secured 251 seats—short of a majority—forcing it to seek ad hoc alliances to pass key reforms.

The mechanics of coalition-building in France are both pragmatic and precarious. Parties must balance ideological alignment with electoral necessity, often forming alliances that span the political spectrum. The *accord électoral* (electoral agreement) is a common tool, where parties agree to withdraw candidates in certain constituencies to avoid splitting the vote. For example, in 2017, the Republican Party and the Union of Democrats and Independents formed a center-right alliance to counter Macron’s centrist bloc. However, such alliances are not without risk; they can alienate purist factions within a party and blur ideological boundaries, potentially leading to voter confusion or disillusionment.

A cautionary tale lies in the 2022 *NUPES* coalition (New Ecologic and Social People’s Union), which united left-wing parties including La France Insoumise, the Socialist Party, the French Communist Party, and Europe Ecology – The Greens. While NUPES emerged as the largest opposition bloc with 131 seats, internal tensions over leadership and policy priorities quickly surfaced. This highlights a critical challenge: coalitions must prioritize shared goals over ideological purity to remain functional. Parties should focus on 2–3 core policy areas (e.g., climate, economic reform) and establish clear decision-making hierarchies to avoid paralysis.

For parties considering alliances, a step-by-step approach is essential. First, conduct a *cartographie politique* (political mapping) to identify potential partners based on overlapping voter bases and policy alignment. Second, negotiate a written agreement outlining shared objectives, candidate distribution, and dispute resolution mechanisms. Third, communicate the alliance’s rationale transparently to voters, emphasizing unity without sacrificing individual party identities. Finally, monitor public sentiment through polling and adjust strategies as needed. For example, in 2024, the *Rassemblement National* (National Rally) has sought to soften its image by forming alliances with smaller conservative parties, a move aimed at broadening its appeal.

The takeaway is clear: coalitions are not just a means to an end but a reflection of France’s pluralistic democracy. While they offer a pathway to power, their success depends on strategic planning, mutual trust, and adaptability. Parties that master the art of alliance-building can navigate the complexities of the French electoral system, ensuring their voices—and those of their constituents—are heard in the National Assembly.

Wealth in Politics: Which Party Holds the Financial Advantage?

You may want to see also

Voter Demographics: Age, region, and socioeconomic factors significantly influence voting patterns and party success

In France, the youth vote has become a pivotal force in shaping electoral outcomes, with voters aged 18-24 increasingly leaning towards progressive and environmentalist parties. For instance, in the 2022 legislative elections, Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s *La France Insoumise* (LFI) garnered 31% of votes from this age group, compared to 11% for Emmanuel Macron’s *La République En Marche!* (LREM). This disparity highlights how younger voters prioritize issues like climate change and social justice, often aligning with left-leaning platforms. Parties aiming to capture this demographic must emphasize actionable policies, such as tuition-free education or green job initiatives, and leverage social media campaigns to engage this tech-savvy cohort effectively.

Regional disparities in France create distinct voting blocs that favor specific parties. The rural regions, like Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes and Occitanie, tend to support conservative parties such as *Les Républicains* (LR), while urban centers like Paris and Lyon lean towards centrist or leftist parties. For example, in the 2022 presidential election, Marine Le Pen’s *Rassemblement National* (RN) secured 35% of votes in the northern Hauts-de-France region, a post-industrial area grappling with economic decline. To tailor campaigns regionally, parties should address localized concerns—rural voters may respond to agricultural subsidies, while urban voters prioritize public transportation and housing affordability.

Socioeconomic status remains a critical determinant of voting behavior in France. Working-class voters, particularly those earning below €20,000 annually, often gravitate towards populist or far-right parties like RN, which promises protectionist economic policies. Conversely, higher-income brackets (above €50,000) disproportionately support LREM or LR, favoring their pro-business stances. A 2021 Ipsos study revealed that 42% of low-income voters cited unemployment as their top concern, compared to 23% of high-income voters who prioritized taxation. Parties can enhance their appeal by aligning policy proposals with these socioeconomic priorities, such as RN’s focus on job security or LREM’s emphasis on tax reforms for the affluent.

To maximize electoral success, parties must adopt a data-driven approach to demographic targeting. For instance, analyzing voter turnout by age reveals that only 40% of 18-24-year-olds voted in the 2021 regional elections, compared to 70% of voters over 65. Campaigns should invest in youth mobilization strategies, such as campus outreach programs or influencer partnerships, to bridge this gap. Similarly, regional campaigns should incorporate local dialects or cultural references to build trust. Socioeconomic targeting could involve door-to-door canvassing in low-income neighborhoods, paired with digital ads tailored to high-income professionals. By dissecting these demographics and tailoring strategies accordingly, parties can transform voter preferences into electoral victories.

Understanding Republican Political Theory: Core Principles and Modern Relevance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political parties in France are elected through a combination of legislative and presidential elections. Members of the National Assembly (the lower house of Parliament) are elected directly by voters in single-member constituencies using a two-round voting system. The President of France is also elected directly by the people through a two-round system.

The two-round voting system ensures that candidates or parties must achieve a majority (over 50%) to win. If no candidate secures a majority in the first round, a second round is held between the top two contenders, allowing for a clearer mandate.

The party or coalition that wins a majority in the National Assembly typically forms the government. The President appoints the Prime Minister from the majority party, who then forms the cabinet. However, if the President's party does not hold a majority, it leads to a situation called "cohabitation," where the President and Prime Minister are from different parties.

The presidential election is pivotal as the President holds significant power, including appointing the Prime Minister, dissolving the National Assembly, and leading foreign policy. The President is elected for a five-year term and plays a central role in shaping the country's political direction.