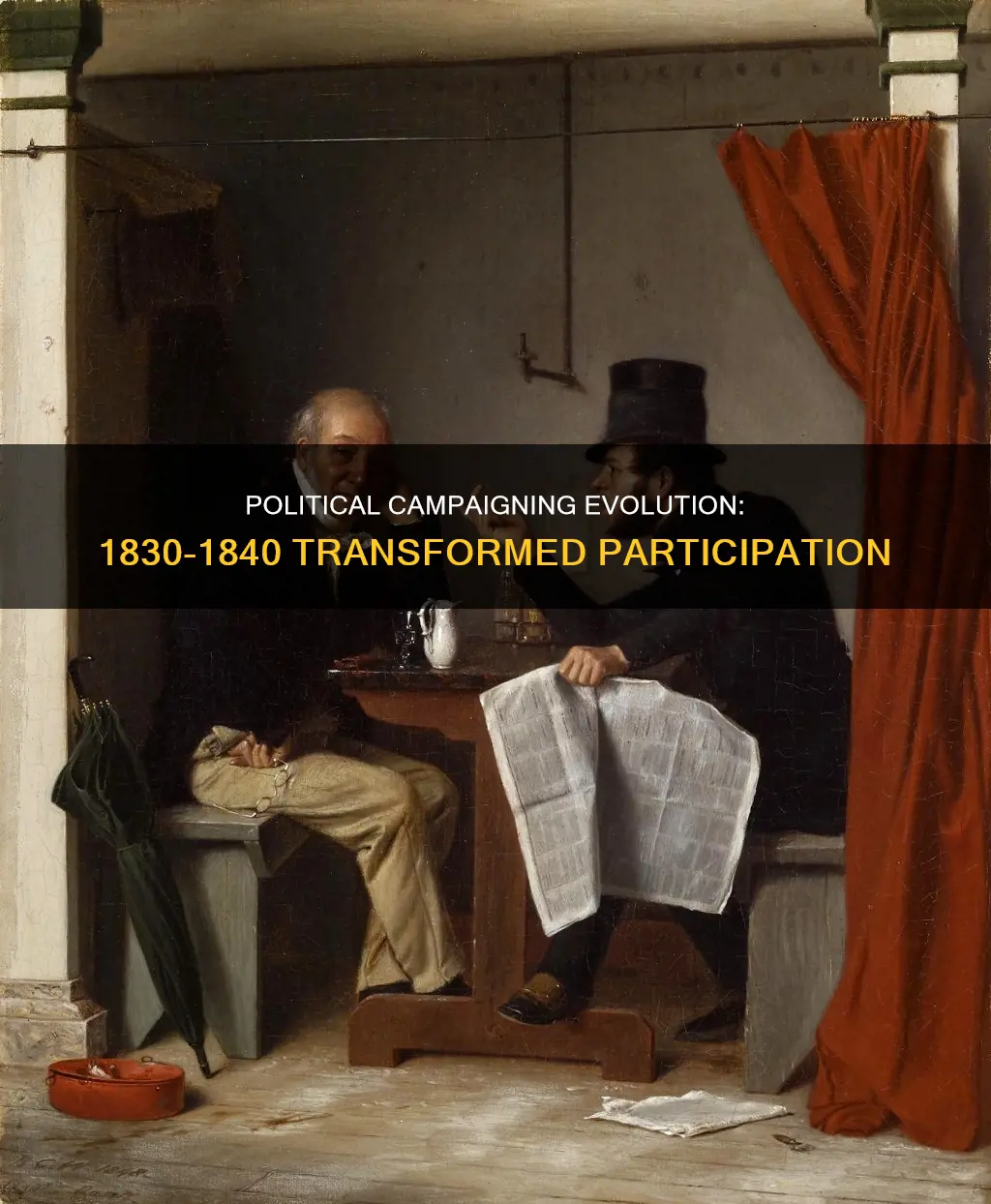

Between 1830 and 1840, political participation in campaigns underwent significant changes in the United States. This period witnessed the emergence of new political parties, a broader voting franchise, and evolving campaign strategies. The War of 1812 and the subsequent Era of Good Feelings played a pivotal role in reshaping the political landscape, fostering a sense of national unity and breaking down old political barriers. The Reform Movement, driven by religious fervor and a range of social issues, also influenced political participation during this time.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political participation | Increased |

| Voter requirements | Reduced |

| Voter unity | Increased |

| Voting participation | Increased |

| Political candidates' appeal | Appealed to the common man |

| Voting franchise | Enlarged |

| Suffrage requirements | Reduced or removed |

| Political parties | Two major parties dominated |

Explore related products

$59.2 $74

$29.22 $33.99

What You'll Learn

- The War of 1812's aftermath: a surge in nationalism, leading to the Era of Good Feelings

- The Reform Movement: religious fervour, social reforms, and women's rights

- Voting franchise expansion: states removing property and tax qualifications for suffrage

- Political parties as armies: hierarchical, disciplined, and led by militia officers

- Campaign strategies: mobilisation of votes, community canvassing, and multiple appeals

The War of 1812's aftermath: a surge in nationalism, leading to the Era of Good Feelings

The War of 1812, sometimes referred to as the Second War of Independence, had a profound impact on the United States, shaping the nation's politics, economics, foreign policy, and culture. The aftermath of the war brought about a surge in nationalism and marked the beginning of the Era of Good Feelings.

The Era of Good Feelings, lasting from 1815 to 1825, was characterised by a strong sense of national pride and unity. The war had united Americans behind a common goal: to improve the nation and assert their independence from Europe. This sense of patriotism and nationalism was reflected in various aspects of American society, including politics, economics, law, and foreign policy. The election of James Monroe as president in 1816 further solidified this era, as he embodied a strong sense of confidence and nationalism.

During this time, there was little political competition as the Federalist Party, the first political party in the United States, fell out of favour due to their opposition to the war. The Democratic-Republican Party, led by James Monroe, rose to power, and Americans rallied behind their vision of a nation of free farmers. This era also witnessed a shift in foreign policy, with the introduction of the Monroe Doctrine, which asserted American dominance in the Western Hemisphere and marked a more aggressive approach to foreign affairs.

The War of 1812 also had a significant impact on the country's economic landscape. The expansion of cotton production and the institution of race-based slavery fueled America's economic engine. However, the issue of slavery continued to divide the nation, setting the stage for the Civil War. Additionally, the war transformed America's public memory, diversifying and democratising it to include the achievements of common soldiers and sailors, with an emphasis on maritime victories.

While the Era of Good Feelings was a time of relative peace and prosperity, it was not without its challenges. The illusion of national consensus was shattered by events such as the panic of 1819 and the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which brought to light the growing sectional tensions and disagreements in politics. Nonetheless, the Era of Good Feelings played a pivotal role in shaping the political landscape of the United States, setting the stage for the expansion of democracy and the emergence of new political parties in the 1830s and 1840s.

Get Involved: Political Campaign Participation Guide

You may want to see also

The Reform Movement: religious fervour, social reforms, and women's rights

The period between 1830 and 1840 was marked by a wave of political participation and reformist fervour in the United States. This era, known as the "Age of Reform", witnessed a diverse array of movements advocating for spiritual and secular transformation. While the underlying reasons for this surge in reformist sentiment are still debated by historians, several factors have been proposed, including the rise of Protestant Evangelicalism, the spread of reformist ideals across the Anglo-American community, and the advancements in 19th-century capitalist communication systems.

Religious Fervour

The 1830s saw a significant increase in religious fervour, with Millennialist beliefs gaining traction among the populace. Preachers like Charles Grandison Finney prophesied that the world would soon end and that sin must be purged before Christ's Second Coming. This religious zeal inspired a range of social crusades, with universal education seen as a key component in achieving a more perfect society. Horace Mann, a prominent educator, advocated for universal free public schooling, reflecting the belief that education was essential for improving the lives of the neglected and abused.

Social Reforms

The expanding industrialization during this period led to a widening class imbalance, as workers became increasingly dependent on the unpredictable business cycle and the benevolence of employers. This spurred economic reformers into action, aiming to enhance the bargaining power of employees through labour unions and cooperative societal reorganization. Labour reformer George Henry Evans, for instance, proposed awarding free farms to labourers to reduce the labour supply and increase wages.

Women's Rights

While the women's rights movement is more famously associated with the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, the groundwork for this movement was laid in the preceding decades. By the 1830s, women across the United States were already questioning the unfair restrictions on their rights and seeking full civil rights. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a key figure in the movement, drew inspiration from the Declaration of Independence to draft a "Declaration of Sentiments", enumerating the areas of life where women faced injustice and demanding equal rights.

Kamala Harris: Understanding Her Campaign Slogan and Its Impact

You may want to see also

Voting franchise expansion: states removing property and tax qualifications for suffrage

The early nineteenth century, particularly the period between 1830 and 1840, witnessed significant changes in political participation in campaigns, with the most notable development being the expansion of voting rights and the removal of property and tax qualifications for suffrage.

By 1830, a shift towards universal white manhood suffrage was evident, with ten states adopting this principle. This represented a significant departure from the restrictions of the early 1800s, when only three states (Kentucky, New Hampshire, and Vermont) allowed all white men to vote. The removal of property qualifications for voting and officeholding was a pivotal political innovation of this era, addressing the demands of those who lacked property and desired a political voice.

During the 1830s, eight states restricted voting rights to taxpayers, and six states still maintained property qualifications for suffrage. However, by 1840, a transformative milestone was achieved, with more than 90% of adult white men gaining the right to vote across the nation. This expansion of suffrage rights was a testament to the growing democratic spirit of the era, which sought to empower all white men, regardless of their economic status, to have a say in the political direction of the country.

It is important to note that this expansion of voting rights did not extend to all segments of society. While white men benefited from the removal of property and tax qualifications, other groups, such as women and African Americans, faced persistent and, in some cases, increasing restrictions on their voting rights. By 1840, almost all white men could vote in all but three states (Rhode Island, Virginia, and Louisiana), yet African Americans were disenfranchised in all but five states, and women were entirely excluded from the political process.

The expansion of voting rights during this period was driven by a combination of factors, including pressure from propertyless men seeking political representation, the ambitions of political parties to widen their support base, and the efforts of territories to attract new settlers by offering them voting rights. This dynamic period in American political history, therefore, witnessed a complex interplay of democratic progress and persistent inequalities, setting the stage for ongoing struggles for suffrage expansion in the decades to come.

How Politicians Win: Strategies to Sway Constituents

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Political parties as armies: hierarchical, disciplined, and led by militia officers

Political parties in the 19th century viewed themselves as armies, with a hierarchical structure and a disciplined, militaristic chain of command. This idea of political parties as armies was perhaps a natural extension of the fact that many political leaders of the time had experience as militia officers.

The party was structured as a disciplined, hierarchical fighting organisation with a clear mission: to defeat an identified opponent. If they were defeated, they knew how to retreat, regroup, and fight again. This militaristic structure was reflected in the way parties conducted themselves, with a clear chain of command. The acknowledged leaders were normally the heads of the state and national tickets. After an election, leadership typically reverted to state and county committees or, sometimes, "state bosses", with little power left for the national chairman.

The county committees, based on local conventions, were open to any self-identified partisan. These mass meetings were an important way to gather supporters and create a loyal "army" of supporters. The basic campaign strategy was to maximise the mobilisation of potential votes. Politicians would canvass their communities, discussing state and national issues and gauging responses to tailor their appeals. This was especially important in a large, complex, and pluralistic nation, where citizens were loyal to their ethno-religious groups.

The early 19th century also saw a general enlargement of the voting franchise, with states removing or reducing property and tax qualifications for suffrage. By the early 1800s, the majority of free adult white males could vote, though this varied by state. This expansion of voting rights, along with the emergence of new social reform movements and a growing sense of nationalism, contributed to significant changes in political participation between 1815 and 1840.

Campaign Finance Laws: Stifling Political Activist Groups?

You may want to see also

Campaign strategies: mobilisation of votes, community canvassing, and multiple appeals

Between 1830 and 1840, political participation in campaigns underwent significant changes due to social and political shifts. This period witnessed the expansion of democracy, with the gradual elimination of property qualifications for voting, granting almost all white men suffrage. However, it also became more restrictive, as African Americans were systematically excluded from suffrage in most states. These factors contributed to a substantial increase in eligible voters, particularly from the middle and lower classes.

Campaign Strategies: Mobilisation of Votes

The changing political landscape prompted new campaign strategies centred on vote mobilisation. The emergence of the "'common man' ideal influenced politicians to appeal to the masses and the growing middle class. Candidates sought to present themselves as defenders of the common people against the elite, leveraging their backgrounds rather than their political views or knowledge. This shift in focus resulted in politicians advocating for legislation benefiting the "common man," addressing issues such as child labour.

Community Canvassing

Community canvassing, or direct contact with individuals, became an integral part of campaign strategies during this period. With the development of the party system in the early 19th century, elections became more contested, and canvassing was employed to visit each voter in a district. This practice was utilised by political parties to identify supporters, persuade undecided voters, and register new voters. However, canvassing also led to instances of corruption, with direct bribery and patronage appointments being offered in exchange for votes.

Multiple Appeals

To attract a broader range of voters, political campaigns employed multiple appeals. For example, in the 1840 election, the Whigs portrayed their candidate, William Henry Harrison, as the "log cabin and hard cider" candidate, a plain man of the country. They aimed to create a relatable image that would appeal to the middle class and contrast with his opponent, Martin Van Buren. The Whigs also adopted a southern strategy by nominating John Tyler, a Virginia senator, as vice president. This balanced their ticket geographically and helped them gain support in the South. Additionally, the Whigs capitalised on the economic collapse of 1837, blaming the Democrats and positioning themselves as advocates for accelerated economic growth.

Political Campaigns: Calls, a Thing of the Past?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The War of 1812, which ended in a stalemate, resulted in an explosion of nationalistic feelings and a sense of pride that destroyed old political barriers and united Americans. This was known as the "Era of Good Feelings". The Reform Movement, driven by the emergence of a new middle class and religious fervor, also played a role in increasing political participation during this time.

Political candidates of the time appealed to the common man by adopting new campaign strategies such as systematically canvassing communities and discussing state and national issues to gauge popular responses. They also used more original techniques, such as appealing to the ethno-religious groups that citizens were especially loyal to.

The enlargement of the voting franchise resulted in almost all white men gaining the right to vote by 1840, while African Americans were excluded from voting in most states. Political parties became more disciplined, hierarchical, and militaristic, resembling armies with clear chains of command.