The number of political parties that can present a presidential candidate varies significantly across different countries, depending on their electoral systems and legal frameworks. In some nations, such as the United States, the two-party system dominates, making it challenging for third parties to gain traction or secure ballot access. Conversely, countries with proportional representation or multi-party systems, like Germany or India, often allow numerous parties to field candidates, fostering greater political diversity. Additionally, eligibility criteria, such as registration requirements, signature thresholds, or financial deposits, can further limit or expand the pool of participating parties. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for analyzing the inclusivity and competitiveness of presidential elections in any given country.

Explore related products

$13.42 $23.4

What You'll Learn

Legal Limits on Nominations

The number of political parties that can nominate a presidential candidate is often constrained by legal frameworks designed to maintain electoral integrity and manage administrative feasibility. In the United States, for instance, federal law requires candidates to secure ballot access in each state, a process that varies significantly. While major parties like the Democrats and Republicans automatically qualify due to their historical performance, minor parties must gather a specific number of signatures or meet other criteria, such as paying a filing fee. This system effectively limits the number of candidates on the ballot, ensuring elections remain manageable for voters and election officials alike.

Consider the case of Brazil, where the legal framework explicitly caps the number of political parties that can participate in presidential elections. With over 30 registered parties, Brazilian law mandates that only parties with a minimum representation in Congress—typically those holding a certain number of seats—can nominate candidates. This threshold ensures that only parties with demonstrable public support can compete, reducing ballot clutter and preventing fringe candidates from overwhelming the system. Such legal limits highlight a balance between democratic inclusivity and practical governance.

In contrast, countries like India adopt a more permissive approach, allowing any registered political party to field a presidential candidate, provided they meet basic eligibility criteria. However, even here, legal limits exist in the form of nomination fees and the requirement for candidates to secure endorsements from a specified number of electors. These measures act as filters, discouraging frivolous nominations while still permitting a diverse range of parties to participate. The takeaway is that even in open systems, legal constraints play a subtle yet crucial role in shaping electoral dynamics.

For nations considering reforms to their nomination laws, a key caution is to avoid overly restrictive measures that stifle political competition. For example, raising signature requirements or filing fees disproportionately can disenfranchise smaller parties, limiting voter choice. Conversely, removing all barriers risks inundating ballots with candidates, potentially confusing voters and diluting the significance of the election. Striking this balance requires careful consideration of a country’s political culture, administrative capacity, and democratic values.

In practice, legal limits on nominations serve as both a shield and a scalpel. They shield elections from chaos by setting clear, enforceable criteria for participation, while also carving out space for legitimate contenders. For policymakers, the challenge lies in designing rules that are transparent, fair, and adaptable to evolving political landscapes. By studying global examples—from Brazil’s restrictive thresholds to India’s inclusive framework—countries can craft nomination laws that foster healthy competition without sacrificing order.

Understanding Symbolic Politics: Meanings, Impacts, and Real-World Applications

You may want to see also

Party Registration Requirements

In the United States, the number of political parties that can present a presidential candidate is theoretically unlimited, but in practice, stringent party registration requirements often limit this number. Each state sets its own rules for ballot access, creating a complex landscape that smaller parties must navigate. For instance, in Texas, a new party must gather signatures equal to 1% of the total votes cast in the last gubernatorial election, while in California, the threshold is a fixed number of registered voters. These varying requirements can make it prohibitively difficult for smaller parties to gain a foothold, effectively narrowing the field to the two major parties.

To register a political party, organizers must typically follow a multi-step process that includes filing a statement of organization, adopting bylaws, and submitting a list of qualified voters. In some states, like New York, parties must also run a candidate for statewide office and secure a minimum percentage of the vote to maintain their status. This system, while designed to ensure legitimacy, can inadvertently stifle political diversity. For example, the Libertarian Party has had to mount legal challenges in several states to secure ballot access, highlighting the barriers faced by third parties.

One of the most contentious aspects of party registration requirements is the signature-gathering process. In states like Illinois, new parties must collect tens of thousands of signatures, a task that requires significant resources and organization. This often favors well-funded parties and leaves grassroots movements at a disadvantage. Moreover, signatures must be verified, a process that can be time-consuming and subject to challenges from opposing parties. Practical tips for organizers include starting early, training volunteers thoroughly, and using digital tools to track progress, though these measures still may not guarantee success.

Comparatively, countries like Germany and India have more inclusive systems. In Germany, parties need only submit a list of members and a platform to be recognized, while in India, parties must demonstrate a regional or national presence but face fewer bureaucratic hurdles. These examples suggest that the U.S. system could be reformed to balance legitimacy with accessibility. For instance, reducing signature requirements or standardizing rules across states could encourage greater political participation without compromising electoral integrity.

Ultimately, party registration requirements serve as both a gatekeeper and a barrier in the U.S. political system. While they aim to prevent frivolous candidacies, they also limit voters' choices and perpetuate a two-party dominance. For smaller parties, understanding and navigating these requirements is essential but often insufficient. Advocates for reform argue that lowering these barriers could lead to a more dynamic and representative political landscape, though such changes would require significant legislative and cultural shifts. Until then, the question of how many parties can present a presidential candidate remains constrained by a system that favors the status quo.

Unveiling Core Values: Exploring Political Parties' Beliefs and Principles

You may want to see also

Nomination Process Rules

The number of political parties that can present a presidential candidate varies widely across countries, shaped by their electoral systems and legal frameworks. In the United States, for instance, the Democratic and Republican parties dominate due to historical precedent and ballot access laws, but third parties like the Libertarians or Greens can also field candidates if they meet stringent state-by-state requirements. In contrast, multiparty democracies like India or Brazil allow numerous parties to nominate candidates, reflecting their diverse political landscapes. This disparity highlights how nomination process rules act as gatekeepers, determining which voices gain access to the highest office.

To understand these rules, consider the steps required for a party to nominate a presidential candidate. First, parties must achieve legal recognition, often through registering with an electoral commission and meeting membership or support thresholds. For example, in Germany, a party must have at least 0.1% of eligible voters as members or demonstrate significant public support. Second, candidates typically need to secure a nomination through internal party processes, such as primaries or caucuses, as seen in the U.S. Third, parties must comply with ballot access laws, which may include collecting a specific number of voter signatures or paying fees. In the U.S., these requirements vary by state, with some demanding tens of thousands of signatures, effectively limiting smaller parties.

A critical analysis of these rules reveals their dual nature: they ensure stability and seriousness in the electoral process but can also stifle political diversity. For instance, while high ballot access thresholds prevent frivolous candidacies, they disproportionately disadvantage smaller parties with limited resources. This imbalance raises questions about fairness and representation. In countries like New Zealand, where proportional representation and lower barriers exist, smaller parties often secure parliamentary seats, enriching political discourse. Such systems suggest that nomination rules can be designed to balance order and inclusivity.

For parties aiming to navigate these rules, practical strategies are essential. Start by thoroughly researching local electoral laws, as requirements differ even within federal systems. Leverage grassroots organizing to meet signature or membership thresholds, and consider coalitions with like-minded groups to pool resources. Fundraising is critical, as campaigns often require significant financial investment to meet legal and logistical demands. Finally, engage legal counsel to ensure compliance with all procedural steps, as minor oversights can lead to disqualification. By approaching the nomination process methodically, parties can maximize their chances of successfully fielding a candidate.

In conclusion, nomination process rules are not merely bureaucratic hurdles but powerful determinants of political participation. They reflect a nation’s values regarding competition, representation, and governance. While stringent rules can maintain system stability, overly restrictive measures risk marginalizing voices and limiting democratic choice. Policymakers and parties alike must strike a balance, ensuring that the process remains fair, accessible, and reflective of the electorate’s diversity. After all, the strength of a democracy is measured not just by who wins, but by who is allowed to compete.

Mastering Statecraft: The Art of Political Strategy and Governance Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$182.59 $55.99

$9.49 $16.95

$21.01 $29.99

Coalition Candidacies

In many democratic systems, the number of political parties that can present a presidential candidate is theoretically unlimited, but practical constraints often limit this to a handful of major contenders. However, coalition candidacies emerge as a strategic response to fragmented political landscapes, where no single party commands sufficient support to win outright. By uniting behind a shared candidate, multiple parties can pool resources, broaden appeal, and increase their chances of victory. This approach is particularly prevalent in proportional representation systems, where smaller parties hold significant influence but lack the individual strength to secure the presidency.

Consider the mechanics of forming a coalition candidacy. First, parties must identify a candidate acceptable to all coalition members, often requiring compromise on policy positions and personal attributes. Second, they must negotiate a joint platform that balances the interests of each party while presenting a cohesive vision to voters. Third, resource allocation—such as funding, campaign staff, and media coverage—must be equitably distributed to maintain unity. For instance, in the 2019 Indonesian presidential election, Joko Widodo’s coalition included nine parties, each contributing to a diverse but coordinated campaign effort. This example underscores the complexity of managing alliances while pursuing a common goal.

Critics argue that coalition candidacies can dilute a candidate’s identity, making it harder for voters to discern their true agenda. However, proponents counter that such alliances foster inclusivity and reflect the diversity of a nation’s political spectrum. In countries like India, where regional parties play a pivotal role, coalition candidates often serve as bridges between national and local interests. For instance, the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) in 2004 demonstrated how a coalition candidacy could successfully challenge a dominant party by leveraging regional strengths and shared grievances against the incumbent.

To maximize the effectiveness of a coalition candidacy, parties should prioritize transparency in negotiations and clearly communicate the rationale behind their alliance to voters. Practical tips include conducting joint rallies to showcase unity, issuing joint statements on key issues, and using digital platforms to amplify the coalition’s message. Additionally, parties should establish conflict resolution mechanisms to address disagreements swiftly, ensuring the coalition remains focused on its shared objective. By doing so, coalition candidacies can transform political fragmentation into a strength rather than a weakness.

Ultimately, coalition candidacies represent a pragmatic solution to the challenges of multiparty democracies, enabling smaller parties to compete effectively in presidential races. While they require careful coordination and compromise, successful coalitions can redefine electoral dynamics and deliver outcomes that reflect a broader consensus. As political landscapes continue to fragment globally, the strategic use of coalition candidacies will likely become an increasingly vital tool for parties seeking to secure power in diverse and divided societies.

Will Politics Monday Continue? Analyzing Its Future and Impact

You may want to see also

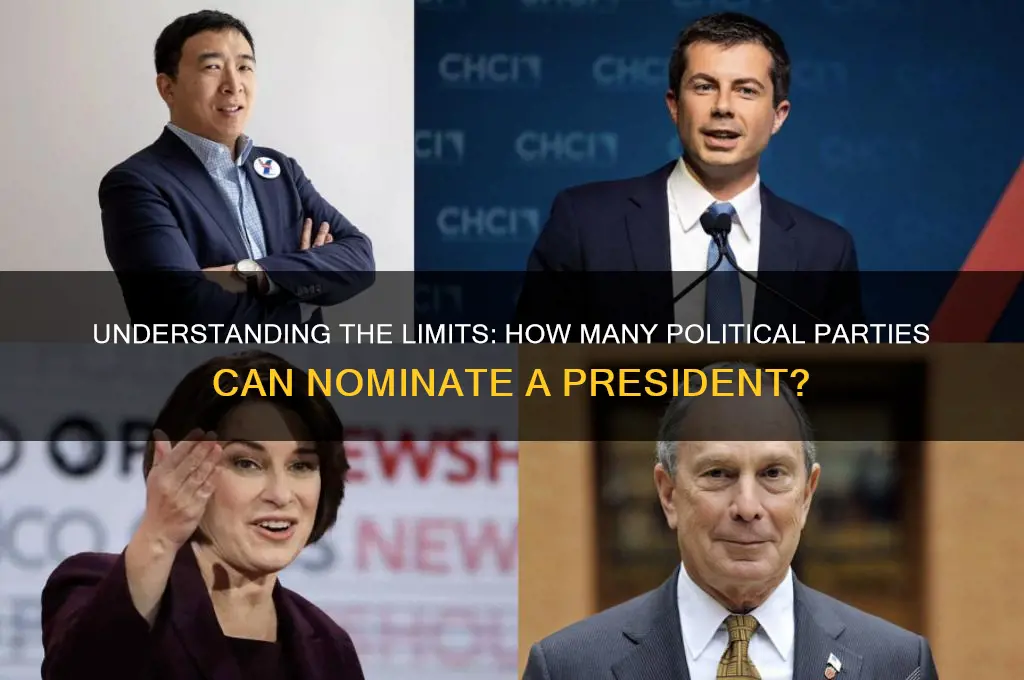

Independent vs. Party Candidates

In the United States, the number of political parties that can present a presidential candidate is theoretically unlimited, but in practice, the two-party system dominates. This reality creates a stark contrast between independent and party-affiliated candidates, each facing distinct challenges and opportunities. Independents, unbound by party platforms, enjoy greater freedom to craft unique messages but must overcome significant hurdles to gain ballot access and visibility. Party candidates, on the other hand, benefit from established infrastructure, funding, and voter recognition but are constrained by party ideologies and internal politics.

Consider the logistical nightmare independents face: to appear on the ballot in all 50 states, they must navigate a patchwork of state-specific requirements, including petition signatures ranging from 3,000 in North Carolina to over 200,000 in California. This process, often costing millions, is a barrier few can surmount. Party candidates bypass this entirely, as their parties are typically pre-qualified for ballot access. For instance, in 2020, Joe Biden and Donald Trump automatically appeared on all state ballots, while independent candidate Kanye West managed to secure a spot in only 12 states. This disparity highlights the structural advantage of party affiliation.

From a persuasive standpoint, independents argue they represent a purer form of democracy, free from partisan gridlock. However, their lack of party backing often translates to limited media coverage and fundraising difficulties. Party candidates, supported by extensive donor networks and super PACs, can outspend independents by orders of magnitude. In 2016, Evan McMullin, an independent candidate, raised $11.3 million, a fraction of the $1.4 billion spent by Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump combined. This financial imbalance underscores the uphill battle independents face in competing with party-backed contenders.

Comparatively, the success of independent candidates is rare but not impossible. Ross Perot in 1992 and 1996 demonstrated that independents can influence the national conversation, though neither won the presidency. Perot’s 19% share of the popular vote in 1992 forced Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush to address issues like the national debt. This example illustrates that while independents may not win, they can shape the political agenda. Party candidates, however, have the advantage of a built-in base, making them more likely to secure the presidency, as evidenced by every U.S. president since 1852 being either a Democrat or Republican.

In conclusion, the choice between running as an independent or party candidate involves a trade-off between autonomy and practicality. Independents offer a refreshing alternative to partisan politics but face formidable obstacles in ballot access, funding, and visibility. Party candidates, while constrained by ideological boundaries, benefit from a well-oiled machine that significantly enhances their chances of success. Aspiring candidates must weigh these factors carefully, recognizing that the path to the presidency is far more accessible with party backing, even if it means sacrificing some independence.

The Tea Party's Rise: Transforming American Politics and Policy

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

In the United States, there is no legal limit to the number of political parties that can present a presidential candidate. Any party or independent candidate can run for president as long as they meet the constitutional requirements and comply with state ballot access laws.

In India, any registered political party recognized by the Election Commission of India can nominate a presidential candidate. There is no cap on the number of parties that can participate, but candidates must secure the support of a specified number of electors to be eligible.

In France, multiple political parties can form alliances and jointly support a single presidential candidate. There is no restriction on the number of parties that can back a candidate, but each candidate must secure a minimum number of sponsorships from elected officials to qualify for the ballot.

![Presidential Nominations and Elections 1916 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UL320_.jpg)