In 1932, Germany’s political landscape was fragmented and polarized, reflecting the deep social and economic turmoil of the Weimar Republic. During this pivotal year, the country had a multitude of political parties spanning the ideological spectrum, from the far-left Communist Party (KPD) to the far-right National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP), led by Adolf Hitler. Other significant parties included the Social Democratic Party (SPD), the Center Party, the German National People’s Party (DNVP), and various regional or interest-based groups. The Reichstag elections of July and November 1932 highlighted this fragmentation, with no single party securing a majority, leading to political instability and paving the way for the rise of the Nazis. This period underscored the challenges of coalition-building and governance in a deeply divided Germany.

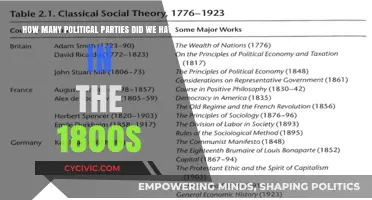

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of Political Parties in Germany (1932) | Approximately 30-40 active parties |

| Major Parties | Nazi Party (NSDAP), Social Democratic Party (SPD), Communist Party (KPD), Centre Party, German National People's Party (DNVP) |

| Political Spectrum | Ranged from far-right (e.g., NSDAP) to far-left (e.g., KPD), with centrist and conservative parties also present |

| Electoral System | Proportional representation, leading to a fragmented parliament (Reichstag) |

| Reichstag Elections (July 1932) | Nazi Party became the largest party with 37.3% of the vote, followed by SPD (21.6%) and KPD (14.3%) |

| Reichstag Elections (November 1932) | Nazi Party's share dropped to 33.1%, while SPD and KPD retained significant support |

| Political Instability | Frequent government changes and inability to form stable coalitions due to ideological divisions |

| Impact of Economic Crisis | Hyperinflation and the Great Depression fueled support for extremist parties like the NSDAP and KPD |

| Role of President Hindenburg | Appointed chancellors, bypassing parliamentary majority, contributing to political instability |

| Rise of the Nazi Party | Exploited political fragmentation and economic hardship to gain power in 1933 |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Major Parties in 1932: Nazi, Communist, Social Democratic, Center, and Nationalist parties dominated the political landscape

- Parliamentary Representation: Reichstag had over 10 parties, reflecting deep political fragmentation during the Weimar Republic

- Rise of Extremism: Nazis and Communists gained significant support, polarizing the electorate in the 1932 elections

- Minor Parties Influence: Smaller groups like the Bavarian People's Party played roles despite limited national impact

- Election Outcomes: July and November 1932 elections showed no party secured a majority, leading to instability

Major Parties in 1932: Nazi, Communist, Social Democratic, Center, and Nationalist parties dominated the political landscape

In 1932, Germany's political landscape was a fragmented yet intensely polarized arena, with five major parties commanding the majority of the Reichstag seats. The Nazi Party (NSDAP), led by Adolf Hitler, emerged as the largest single party, winning 230 seats in the July election and 196 in November. This surge reflected widespread discontent with the Weimar Republic's economic and political instability, as Hitler's promises of national revival resonated with a disillusioned electorate. However, the Nazis were far from achieving a majority, necessitating a coalition to govern—a prospect complicated by their extremist ideology.

The Communist Party (KPD), with 89 seats in July and 100 in November, represented the other extreme of the political spectrum. Fiercely opposed to both the Nazis and the Social Democrats, the KPD focused on revolutionary socialism and class struggle. Their rigid stance, influenced by Soviet directives, alienated potential allies and deepened political divisions. Despite their significant parliamentary presence, the KPD's inability to form coalitions left them largely isolated, contributing to the paralysis of the Reichstag.

The Social Democratic Party (SPD), holding 133 seats in July and 121 in November, was the largest moderate party but faced a dilemma. As defenders of the Weimar Republic, they sought to uphold democracy but refused to collaborate with the Nazis or Communists. This principled stance, while admirable, limited their political maneuverability. The SPD's decline in support mirrored the erosion of faith in the Republic itself, as voters turned to more radical alternatives in desperation.

The Center Party, with 75 seats in July and 70 in November, played a pivotal role as a potential kingmaker. Rooted in Catholic conservatism, it sought to bridge the divide between left and right. However, its moderate position made it a target for both extremes, and its influence waned as polarization intensified. The Center Party's inability to form a stable coalition underscored the fragility of Germany's political system.

Finally, the Nationalist parties, including the German National People's Party (DNVP) and smaller groups, collectively held around 50 seats. These parties, advocating for a return to authoritarian rule and revanchism, often aligned with the Nazis on key issues. Their support for Hitler's chancellorship in January 1933 proved decisive, as it provided the Nazis with the parliamentary legitimacy needed to consolidate power. Together, these five parties dominated the Reichstag, yet their mutual antagonism and ideological rigidity ensured that no stable government could emerge, paving the way for the Nazis' rise.

West Virginia Mountaineers: Unveiling Political Leanings and Campus Culture

You may want to see also

Parliamentary Representation: Reichstag had over 10 parties, reflecting deep political fragmentation during the Weimar Republic

The Reichstag elections of 1932 showcased a staggering diversity of political parties, with over 10 vying for representation. This multiplicity was not a sign of robust democracy but rather a symptom of the Weimar Republic's profound political fragmentation. The parliament's composition resembled a mosaic of competing ideologies, from the far-right National Socialists to the Communist Party, with centrist and regional parties filling the spectrum in between. Each party's presence underscored the inability of any single group to dominate, leading to a legislative body more adept at deadlock than decision-making.

Analyzing this fragmentation reveals the structural weaknesses of the Weimar Republic. The proportional representation system, while democratic in theory, amplified minor parties' influence, often at the expense of governability. For instance, the 1932 elections saw the Nazi Party and the Communists together secure over 50% of the seats, yet their ideological opposition rendered coalition-building nearly impossible. This polarization mirrored societal divisions, as economic crises and wartime grievances fueled support for extremist agendas. The Reichstag's diversity thus became a microcosm of Germany's broader instability.

To understand the practical implications, consider the legislative process during this period. Passing laws required navigating a labyrinth of party interests, with each faction leveraging its modest representation to block or dilute reforms. The government's inability to enact decisive policies exacerbated public disillusionment, further eroding trust in democratic institutions. This gridlock was not merely procedural but existential, as it left the republic vulnerable to authoritarian alternatives promising swift action and unity.

A comparative perspective highlights the uniqueness of Germany's situation. While multi-party systems exist in many democracies, the Weimar Republic's fragmentation was extreme, even by interwar standards. Unlike Britain or France, where two or three major parties dominated, Germany's political landscape was atomized, reflecting deeper societal fractures. This distinction is crucial for understanding why the republic collapsed under pressure, while other democracies weathered similar challenges.

Instructively, the Reichstag's fragmentation offers a cautionary tale for modern democracies. It underscores the importance of balancing representation with governability, ensuring that electoral systems foster stability without stifling diversity. For policymakers today, the lesson is clear: addressing societal divisions requires more than proportional representation; it demands inclusive institutions capable of bridging ideological gaps. Practical steps include electoral reforms that incentivize coalition-building and public policies that address root causes of polarization, such as economic inequality and cultural alienation. By learning from the Weimar Republic's failures, contemporary democracies can avoid the pitfalls of fragmentation while preserving pluralism.

Hamilton's Legacy: Shaping Arizona's Political Landscape and Future

You may want to see also

Rise of Extremism: Nazis and Communists gained significant support, polarizing the electorate in the 1932 elections

In 1932, Germany's political landscape was a fragmented mosaic, with over 20 political parties vying for influence. Among this crowded field, the rise of extremism stood out as a defining trend, with the Nazi Party (NSDAP) and the Communist Party (KPD) gaining unprecedented support. These two polar opposites on the political spectrum capitalized on widespread discontent, economic hardship, and disillusionment with the Weimar Republic. Their ascent was not just a reflection of ideological appeal but also a symptom of a deeply divided society.

The Nazis, led by Adolf Hitler, harnessed the frustrations of a nation humiliated by World War I and crippled by the Great Depression. Their promises of national revival, racial purity, and economic stability resonated with millions, particularly the middle class and unemployed youth. The NSDAP's aggressive propaganda campaigns, charismatic leadership, and paramilitary presence created an aura of inevitability around their rise. By 1932, they had become the largest party in the Reichstag, securing 37.3% of the vote in the July elections and 33.1% in November.

Meanwhile, the Communists, under the banner of the KPD, appealed to the working class and those radicalized by the economic crisis. Their platform of revolution, class struggle, and opposition to capitalism attracted significant support, particularly in urban areas. The KPD's share of the vote rose to 16.9% in July 1932, making them the third-largest party. However, their inability to form alliances with other left-wing parties, coupled with their ideological rigidity, limited their broader appeal.

The simultaneous rise of these extremist parties polarized the electorate, creating a toxic political environment. Moderate parties, such as the Social Democrats (SPD) and the Center Party, struggled to maintain relevance as voters gravitated toward more radical solutions. The Reichstag became a battleground of ideological extremes, with little room for compromise. This polarization paralyzed governance, as no single party could form a stable majority, leading to a series of short-lived coalition governments.

The takeaway from this period is clear: extremism thrives in times of crisis and division. The Nazis and Communists exploited Germany's vulnerabilities, offering simplistic solutions to complex problems. Their success was not just a failure of the Weimar Republic but also a warning about the dangers of political fragmentation and the erosion of democratic norms. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for recognizing how similar patterns can emerge in contemporary societies facing economic instability, social unrest, and disillusionment with traditional leadership.

How to Change Your Political Party Affiliation in New Hampshire

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Minor Parties Influence: Smaller groups like the Bavarian People's Party played roles despite limited national impact

In 1932, Germany's political landscape was fragmented, with over 20 parties vying for influence in the Reichstag. Among these, the Bavarian People's Party (BVP) stands out as a prime example of how minor parties could exert significant regional influence despite their limited national impact. The BVP, a conservative Catholic party, dominated Bavarian politics, shaping local policies and cultural identity. This regional stronghold allowed the BVP to negotiate coalitions and influence national legislation, even as larger parties like the Nazis and Social Democrats dominated headlines.

Consider the BVP's strategic positioning: by focusing on regional issues such as autonomy and religious rights, they secured a loyal voter base in Bavaria. This localized approach enabled them to win seats in the Reichstag, where they could advocate for Bavarian interests. For instance, the BVP successfully pushed for amendments to the Enabling Act of 1933, ensuring Bavaria's cultural and administrative autonomy was protected—albeit temporarily. This demonstrates how minor parties could leverage regional strength to impact national decisions, even in a highly polarized political environment.

However, the BVP's influence was not without limitations. Their narrow focus on Bavarian concerns often marginalized them in broader national debates. While they could negotiate concessions, their inability to form a unified front with other minor parties weakened their overall impact. This highlights a critical lesson: minor parties must balance regional advocacy with strategic alliances to maximize their influence. Without such coalitions, their power remains localized and vulnerable to larger parties' dominance.

Practical takeaways for modern minor parties include the importance of cultivating a strong regional identity while remaining open to cross-party collaborations. For instance, minor parties today can emulate the BVP's focus on local issues to build a dedicated voter base. Simultaneously, they should seek opportunities to align with other parties on shared national concerns, such as environmental policies or economic reforms. This dual approach ensures relevance at both regional and national levels, amplifying their influence beyond their size.

In conclusion, the Bavarian People's Party exemplifies how minor parties can shape political outcomes through regional strength and strategic engagement. While their impact may be limited nationally, their ability to protect local interests and influence legislation underscores the value of localized political power. For contemporary minor parties, the BVP's legacy offers a blueprint for relevance: focus on regional strengths, but never underestimate the power of strategic alliances in a fragmented political landscape.

Step-by-Step Guide to Joining Nigeria's APC Political Party

You may want to see also

Election Outcomes: July and November 1932 elections showed no party secured a majority, leading to instability

The 1932 German federal elections, held in July and November, revealed a deeply fractured political landscape. With over 30 parties competing for seats in the Reichstag, no single party emerged with a clear majority. The July election saw the Nazi Party (NSDAP) win the most votes, securing 37.3% of the total, but this still left them far short of the 50% needed to govern alone. The November election, though showing a slight decline in Nazi support to 33.1%, similarly failed to produce a majority for any party. This inability to form a stable coalition government exacerbated Germany's political and economic instability, setting the stage for the dramatic events that followed.

Analyzing these outcomes, it becomes clear that the Weimar Republic's proportional representation system, while democratic in intent, contributed to its own downfall. The system allowed even small parties to gain representation, leading to a highly fragmented parliament. In 1932, this fragmentation was particularly acute, with parties ranging from the Communist Party (KPD) on the far left to the conservative German National People's Party (DNVP) on the right. The lack of a dominant centrist bloc made coalition-building nearly impossible, as ideological differences were too vast to bridge. This paralysis in governance left the country vulnerable to extremist forces, particularly the Nazis, who capitalized on public frustration with political gridlock.

From a practical standpoint, the instability caused by these elections had immediate and severe consequences. Chancellor Franz von Papen, appointed by President Paul von Hindenburg after the July election, struggled to govern without parliamentary support. His reliance on presidential decrees further undermined the legitimacy of the Weimar system. Similarly, the November election did little to improve the situation, as parties continued to prioritize ideological purity over compromise. This inability to form a stable government created a power vacuum that Adolf Hitler and the Nazis were all too eager to fill, ultimately leading to Hitler's appointment as Chancellor in January 1933.

Comparatively, the 1932 elections stand in stark contrast to the relative stability of earlier Weimar governments. In the 1920s, centrist parties like the Social Democrats (SPD) and the Catholic Center Party had managed to form coalitions, albeit fragile ones. However, by 1932, the economic crisis of the Great Depression had radicalized large segments of the population, pushing them toward extremist parties. The Nazis and Communists, in particular, gained ground by offering simplistic solutions to complex problems, further polarizing the political landscape. This polarization ensured that no moderate coalition could emerge, leaving the country in a state of perpetual crisis.

In conclusion, the July and November 1932 elections were not just a reflection of Germany's political fragmentation but a catalyst for its descent into authoritarianism. The inability of any party to secure a majority, combined with the refusal of major parties to cooperate, created an environment ripe for exploitation. The lessons from this period are clear: in times of economic and social upheaval, democratic systems must prioritize stability and compromise over ideological rigidity. Failure to do so can lead to the erosion of democratic institutions and the rise of extremist forces, as Germany tragically demonstrated.

Are Political Parties Gaining Strength in Today's Polarized Landscape?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

In 1932, Germany had a multi-party system with numerous political parties, including the Nazi Party (NSDAP), the Social Democratic Party (SPD), the Communist Party (KPD), the Center Party, the German National People's Party (DNVP), and several smaller regional or interest-based parties.

No, the major parties like the Nazi Party (NSDAP), the Social Democratic Party (SPD), and the Communist Party (KPD) were the most influential, dominating elections and political discourse, while smaller parties had limited impact.

Yes, after the Nazi Party seized power in 1933, all other political parties were banned or dissolved, leading to a one-party dictatorship under Adolf Hitler.

1932 was significant because it saw two federal elections (July and November) that highlighted the rise of the Nazi Party, which became the largest party in the Reichstag, setting the stage for Hitler's appointment as Chancellor in 1933.