Land, as a fundamental resource, profoundly shapes political systems, ideologies, and power dynamics across societies. Its distribution, fertility, and strategic location influence economic opportunities, social hierarchies, and cultural identities, which in turn dictate political structures and governance. For instance, fertile lands often become centers of wealth and power, fostering centralized authorities, while arid or fragmented terrains may encourage decentralized systems or conflict over scarce resources. Historically, control over land has driven colonization, warfare, and policy-making, with land ownership often determining political representation and influence. Moreover, land’s role in shaping borders, trade routes, and migration patterns further underscores its geopolitical significance, making it a cornerstone of political organization and contestation. Understanding how land molds politics is essential to grasping the roots of inequality, conflict, and cooperation in human societies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Geography and Terrain | Mountainous regions often lead to decentralized political systems, while flat, fertile lands may foster centralized governance. Example: Switzerland's federalism vs. Egypt's historical centralization. |

| Resource Distribution | Areas rich in natural resources (e.g., oil, minerals) often experience political conflicts or authoritarian regimes. Example: The "resource curse" in countries like Venezuela or Nigeria. |

| Borders and Boundaries | Landlocked countries may face economic and political isolation, while coastal nations often have stronger trade networks. Example: Bolivia's landlocked status vs. Singapore's maritime advantage. |

| Agricultural Potential | Fertile lands support larger populations and stable economies, influencing political stability. Example: The U.S. Midwest's agricultural dominance and political influence. |

| Climate and Environment | Harsh climates (e.g., deserts, tundra) limit population density and economic activity, shaping political priorities. Example: Arctic nations' focus on climate policy. |

| Strategic Location | Countries at geopolitical crossroads (e.g., Turkey, Israel) often play significant roles in regional and global politics. |

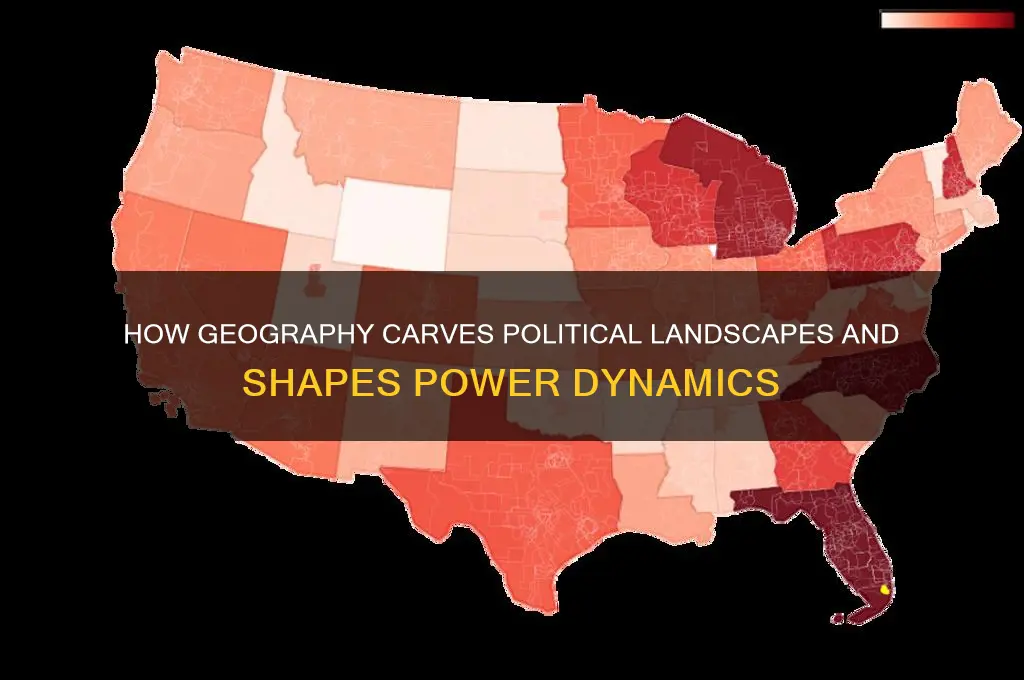

| Urbanization and Land Use | Urban centers concentrate political power, while rural areas may demand decentralized policies. Example: The urban-rural divide in U.S. politics. |

| Historical Land Ownership | Historical land distribution (e.g., feudal systems, colonial legacies) shapes modern political inequalities. Example: Latin America's land reform challenges. |

| Infrastructure Development | Land-based infrastructure (e.g., roads, railways) influences political connectivity and regional development. Example: China's Belt and Road Initiative. |

| Environmental Policies | Land degradation, deforestation, and climate change drive political agendas and international cooperation. Example: The Paris Agreement's focus on land use. |

Explore related products

$12.24 $18

What You'll Learn

- Geography and Borders: How natural features like rivers, mountains, and deserts influence political boundaries

- Resource Distribution: Control over fertile land, minerals, and water shapes political power and conflicts

- Urban vs. Rural Politics: Land use differences drive distinct political priorities and voting behaviors

- Territorial Disputes: Competing claims over land lead to political tensions and international conflicts

- Environmental Policies: Land degradation, conservation, and climate change impact political agendas and legislation

Geography and Borders: How natural features like rivers, mountains, and deserts influence political boundaries

Natural barriers like mountains and deserts have long served as default political boundaries, their imposing presence dictating the limits of human control. The Himalayas, for instance, have historically separated the Indian subcontinent from Tibet and China, not merely as a physical divide but as a cultural and political one. These features, often impassable or requiring significant resources to traverse, naturally restrict movement and interaction, fostering distinct political entities on either side. The Sahara Desert similarly isolates North Africa from sub-Saharan Africa, shaping trade routes, migration patterns, and the rise of distinct civilizations. Such barriers not only define borders but also influence the internal cohesion and external relations of the states they enclose.

Rivers, in contrast, often act as both unifiers and dividers, their dual role shaping political boundaries in complex ways. The Rhine River, for example, has historically served as a natural border between nations, yet it also facilitates trade and communication, making it a contested zone. During the Roman Empire, the Rhine marked the limit of Roman expansion, but it also became a vital trade route linking the empire to Germanic tribes. Similarly, the Nile River has been central to Egyptian identity and politics, its fertile banks fostering a unified civilization while its course delineates Egypt’s southern boundary. Rivers thus embody a paradox: they can both connect and separate, their influence on political boundaries depending on how societies choose to utilize or contest them.

Mountains, while often seen as barriers, can also serve as strategic assets, influencing political boundaries through their control over resources and movement. The Andes, for instance, have shaped the political geography of South America, acting as a spine that both divides and unifies nations. Bolivia and Peru, nestled in the Andean highlands, have distinct political identities rooted in their mountainous terrain, while the range also serves as a natural barrier against external influence. Conversely, the lack of natural mountain barriers in the European plains has historically led to fluid and contested borders, with political boundaries shifting frequently through conflict and negotiation. Mountains, therefore, are not just passive features but active players in the creation and maintenance of political borders.

Deserts, with their harsh climates and limited resources, often discourage settlement and central authority, leading to sparsely populated borderlands that are difficult to govern. The Australian Outback, for example, remains largely ungoverned and uninhabited, its vast expanse resisting political control. However, deserts can also become zones of strategic importance, as seen in the Middle East, where oil reserves beneath the desert sands have made regions like the Arabian Peninsula focal points of global politics. Here, political boundaries are not shaped by the desert’s inhospitability but by the wealth it conceals, illustrating how natural features can paradoxically both hinder and drive political influence.

Understanding the interplay between geography and borders requires a nuanced approach, recognizing that natural features are not deterministic but rather provide a framework within which political decisions are made. For instance, while the Amazon Rainforest might seem an obvious natural boundary, its dense vegetation has not prevented territorial disputes between Brazil, Peru, and Colombia. Instead, the rainforest’s resources have become a point of contention, with political boundaries shifting based on economic interests and military capabilities. This highlights the dynamic relationship between land and politics: natural features set the stage, but human actions ultimately write the script. To navigate this complexity, policymakers must consider not only the physical constraints of geography but also the social, economic, and strategic factors that shape how borders are drawn and defended.

Sports and Politics: A Complex Intersection of Power and Play

You may want to see also

Resource Distribution: Control over fertile land, minerals, and water shapes political power and conflicts

The fertile crescent, a region often regarded as the cradle of civilization, owes its historical significance to the rich soil between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Control over this land enabled early societies to develop agriculture, surplus food production, and, consequently, complex political systems. Today, fertile land remains a cornerstone of political power. Nations with abundant arable land, such as the United States and India, often wield greater economic influence due to their ability to sustain large populations and export agricultural goods. Conversely, countries with limited fertile land, like Egypt, must navigate political tensions to secure food imports or develop irrigation systems, highlighting how resource distribution directly shapes governance and international relations.

Consider the strategic importance of minerals, which have historically fueled both economic growth and geopolitical conflicts. The Democratic Republic of Congo, rich in cobalt and coltan—essential for electronics—has endured decades of civil war as armed groups and foreign powers vie for control over these resources. Similarly, oil-rich nations like Saudi Arabia and Venezuela have leveraged their mineral wealth to assert political dominance regionally and globally. However, this control often comes at a cost: resource-dependent economies can suffer from the "resource curse," where wealth concentration leads to corruption, inequality, and political instability. Policymakers must balance exploitation with sustainable practices to avoid these pitfalls.

Water, the most fundamental resource, is increasingly becoming a flashpoint for political conflict as climate change exacerbates scarcity. The Indus River, shared by India and Pakistan, is a prime example of how water distribution can strain diplomatic relations. Treaties like the Indus Waters Treaty (1960) aim to mitigate disputes, but rising demand and diminishing supplies threaten to destabilize such agreements. In Africa, the Nile River Basin illustrates similar challenges, with upstream countries like Ethiopia constructing dams to harness hydroelectric power, while downstream Egypt fears reduced water flow. These cases underscore the need for cooperative water management frameworks to prevent resource-driven conflicts.

To navigate the complexities of resource distribution, governments and international organizations must adopt multifaceted strategies. First, invest in infrastructure to optimize resource use—for instance, drip irrigation systems can reduce water consumption in agriculture by up to 50%. Second, diversify economies to lessen dependence on a single resource, as Norway has done by investing oil revenues into a sovereign wealth fund. Third, foster regional cooperation through treaties and joint projects, such as the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy. Finally, prioritize transparency and equitable distribution to prevent resource wealth from becoming a tool of political oppression. By addressing these challenges proactively, societies can transform resource distribution from a source of conflict into a foundation for stability and growth.

Is Hobbes a Political Theorist? Exploring His Legacy and Influence

You may want to see also

Urban vs. Rural Politics: Land use differences drive distinct political priorities and voting behaviors

The physical landscape of a community—its density, infrastructure, and natural resources—fundamentally shapes its political priorities. Urban areas, characterized by high population density and limited land availability, often prioritize issues like public transportation, affordable housing, and environmental sustainability. In contrast, rural regions, with their expansive land and lower population density, focus on agricultural policies, land conservation, and infrastructure maintenance. These land-use differences create distinct political ecosystems, where the needs of the terrain dictate the agenda.

Consider the example of zoning laws. In cities, zoning regulations are frequently debated as tools to manage overcrowding, preserve green spaces, and balance commercial and residential development. Urban voters tend to support candidates who advocate for smart growth and equitable land use. In rural areas, however, zoning laws are often viewed with skepticism, as they can restrict farming practices or limit property rights. Rural voters prioritize candidates who promise to protect their ability to use land freely, reflecting a deep connection to the land as both livelihood and identity.

This divergence extends to voting behaviors. Urban populations, often more diverse and exposed to global issues, lean toward progressive policies that address inequality and climate change. Rural voters, rooted in local economies and traditions, tend to favor conservative policies that emphasize individual freedoms and economic stability. For instance, urban voters might champion public transit funding, while rural voters advocate for highway repairs. These preferences are not arbitrary but are directly tied to the practical realities of their environments.

To bridge the urban-rural political divide, policymakers must recognize the role of land use in shaping priorities. A one-size-fits-all approach rarely succeeds. Instead, tailored solutions—such as urban-focused green initiatives paired with rural agricultural subsidies—can address specific needs. Practical tips include engaging local communities in land-use planning, leveraging technology to connect rural and urban areas, and fostering dialogue to highlight shared interests, such as sustainable development. By understanding how land drives politics, leaders can craft policies that resonate across geographies.

Ultimately, the urban-rural divide is not just a cultural or ideological gap but a reflection of how land use molds political identities. Urban and rural communities are not inherently opposed; their differences stem from the distinct challenges and opportunities their landscapes present. Acknowledging this can transform political discourse from conflict to collaboration, ensuring that policies are both effective and equitable.

Measuring Politics: Methods Political Scientists Use to Quantify Data

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$80.74 $84.99

$152 $190

$54.99 $54.99

Territorial Disputes: Competing claims over land lead to political tensions and international conflicts

Territorial disputes have long been a flashpoint for political tensions and international conflicts, often escalating into prolonged standoffs or outright warfare. The roots of these disputes lie in competing claims over land, driven by historical grievances, strategic interests, or resource exploitation. For instance, the South China Sea dispute involves multiple nations asserting sovereignty over islands, reefs, and maritime zones, fueled by access to lucrative fishing grounds, oil reserves, and control over vital trade routes. Such conflicts highlight how land—or in this case, sea—becomes a catalyst for geopolitical rivalry, with far-reaching consequences for regional stability and global diplomacy.

To navigate territorial disputes effectively, it’s essential to understand the underlying motivations of the parties involved. Claims often stem from a mix of legal, historical, and cultural arguments, making resolution complex. For example, the Israel-Palestine conflict centers on competing narratives of land ownership, religious significance, and national identity, complicating efforts to broker peace. A practical approach involves leveraging international law, such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), to establish frameworks for negotiation. However, even legal mechanisms can falter when political will is lacking, underscoring the need for diplomatic creativity and compromise.

One instructive strategy for mitigating territorial disputes is the use of joint development agreements, where contested areas are managed cooperatively rather than exclusively. The 1959 Antarctic Treaty serves as a model, setting aside territorial claims in favor of scientific collaboration and environmental protection. Similarly, China and the Philippines have explored joint oil exploration in the South China Sea, though such efforts often face domestic political backlash. This approach requires trust-building measures, such as confidence-building exercises and third-party mediation, to ensure all parties perceive fairness and mutual benefit.

Despite these efforts, territorial disputes remain a persistent challenge, often exacerbated by nationalist rhetoric and domestic political pressures. Leaders frequently use land claims to rally public support, making concessions politically risky. For instance, Japan and Russia’s dispute over the Kuril Islands has lingered for decades, with both sides unwilling to compromise due to internal political constraints. Breaking this cycle demands long-term vision and a willingness to prioritize regional stability over short-term gains. International organizations and mediators play a critical role here, offering neutral platforms for dialogue and incentivizing peaceful resolution.

In conclusion, territorial disputes are a stark reminder of how land shapes politics, often in destabilizing ways. Resolving these conflicts requires a multi-faceted approach: legal frameworks to clarify claims, diplomatic ingenuity to foster cooperation, and political courage to overcome domestic resistance. While no single solution fits all cases, the lessons from successful resolutions—such as the 1984 treaty between China and the UK over Hong Kong—offer hope. By addressing the root causes of disputes and promoting shared interests, nations can transform contested land from a source of conflict into a foundation for collaboration.

Is Kazakhstan Politically Stable? Analyzing Its Current Political Landscape

You may want to see also

Environmental Policies: Land degradation, conservation, and climate change impact political agendas and legislation

Land degradation, a silent crisis unfolding across the globe, has become a pivotal issue in shaping environmental policies and political agendas. Every year, an estimated 12 million hectares of land are lost to degradation, primarily due to deforestation, overgrazing, and unsustainable agricultural practices. This not only threatens food security but also exacerbates poverty, particularly in developing nations where 65% of the population depends on land for livelihood. Governments are increasingly recognizing that addressing land degradation is not just an environmental imperative but a political necessity. Policies such as the African Union’s Great Green Wall initiative, which aims to restore 100 million hectares of degraded land by 2030, exemplify how land restoration can become a cornerstone of political strategy, fostering regional cooperation and economic resilience.

Conservation efforts, on the other hand, highlight the tension between economic development and environmental sustainability, often placing politicians in a delicate balancing act. Protected areas now cover nearly 15% of the Earth’s land surface, yet illegal logging, mining, and encroachment continue to undermine these efforts. In countries like Costa Rica, where 26% of the land is protected, conservation has been integrated into national identity and economic policy, with ecotourism contributing over $3 billion annually. Such success stories demonstrate that conservation can be a political win, but they also underscore the need for robust enforcement mechanisms and community engagement. Legislators must navigate these complexities, ensuring that conservation policies are not only ambitious but also equitable and enforceable.

Climate change amplifies the urgency of land-related policies, as its impacts—droughts, floods, and desertification—disproportionately affect vulnerable populations. For instance, the Sahel region in Africa has experienced a 10% reduction in arable land over the past 50 years due to climate-induced desertification, displacing millions. Political responses to such crises often involve cross-sectoral policies, such as India’s National Action Plan on Climate Change, which links land management, water conservation, and renewable energy. However, the effectiveness of these policies hinges on international cooperation and funding. The Green Climate Fund, for example, has pledged $100 billion annually to support developing countries in mitigating and adapting to climate change, but disbursement and implementation remain fraught with challenges.

The interplay between land degradation, conservation, and climate change demands a paradigm shift in political thinking, one that prioritizes long-term sustainability over short-term gains. Policymakers must adopt integrated approaches, such as agroforestry and sustainable land management practices, which can simultaneously combat degradation, enhance biodiversity, and sequester carbon. For instance, Ethiopia’s Tigray region has successfully rehabilitated over 1 million hectares of degraded land through community-led initiatives, reducing soil erosion by 80% and increasing crop yields by 40%. Such examples illustrate the transformative potential of land-centric policies when backed by political will and grassroots participation.

Ultimately, the political agendas of the 21st century will be defined by how effectively nations address the intertwined challenges of land degradation, conservation, and climate change. This requires not only bold legislation but also innovative financing mechanisms, technological advancements, and public awareness campaigns. As land continues to shape politics, the choices made today will determine the resilience of ecosystems, economies, and societies for generations to come. The question is not whether land matters in politics, but how deeply its stewardship will be embedded in the fabric of governance.

Graceful Goodbyes: How to End Dating Relationships with Kindness and Respect

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Geography plays a crucial role in shaping political boundaries by creating natural barriers like rivers, mountains, or deserts, which often serve as dividing lines between nations. It also influences resource distribution, trade routes, and defensibility, all of which impact the formation and stability of political entities.

Fertile land is a key resource that often determines economic strength and political influence. Control over fertile regions can lead to wealth accumulation, population growth, and military power, making it a frequent source of conflict between groups or nations vying for dominance.

Terrain shapes governance by influencing communication, transportation, and economic activities. For example, mountainous regions may foster decentralized political systems due to isolation, while flat, fertile plains often support centralized authority. Terrain also affects the ability to enforce laws and collect taxes, shaping the structure of political institutions.