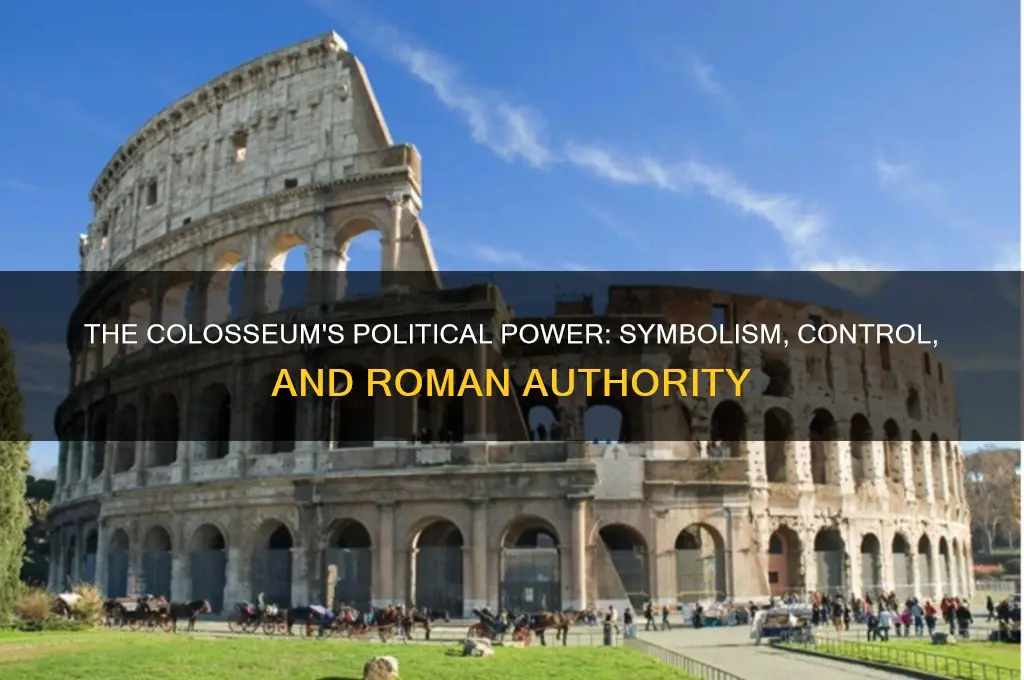

The Colosseum, an iconic symbol of ancient Rome, transcends its role as an architectural marvel and entertainment venue to embody profound political significance. Built under Emperor Vespasian and completed by his son Titus in 80 AD, it served as a tool for political propaganda, reinforcing the Flavian dynasty’s legitimacy and generosity through its construction and public games. The amphitheater’s massive scale and grandeur reflected Rome’s imperial power, while the games themselves—funded by the spoils of war, particularly the Jewish Revolt—demonstrated Roman dominance and rewarded the populace, fostering loyalty to the ruling elite. Additionally, the Colosseum’s seating arrangement, strictly divided by social class, reinforced the hierarchical structure of Roman society, cementing the political and social order. Thus, the Colosseum was not merely a site of spectacle but a strategic instrument of political control and ideology in the Roman Empire.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Symbol of Imperial Power | The Colosseum was commissioned by Emperor Vespasian to showcase the might of the Flavian dynasty and Roman Empire. |

| Public Entertainment as Control | Gladiatorial games and events were used to distract the populace and maintain social order, reducing political unrest. |

| Architectural Propaganda | Its grand design and scale symbolized Roman engineering prowess and imperial dominance. |

| Distribution of Resources | Free grain and entertainment (like Colosseum events) were part of the panem et circenses policy to appease the masses. |

| Political Legitimacy | Emperors used the Colosseum to gain popularity and legitimize their rule through public spectacles. |

| Social Hierarchy Reinforcement | Seating arrangements reflected social class, reinforcing the political and social order. |

| Military and Conquest Celebration | Events often included re-enactments of battles, celebrating Roman military victories and imperial expansion. |

| Economic Influence | Construction and maintenance of the Colosseum stimulated the economy, benefiting the ruling elite. |

| Cultural Dominance | The Colosseum represented Roman cultural superiority, a key aspect of political ideology. |

| Legacy as Political Tool | Even today, the Colosseum is used as a symbol of Rome’s historical political influence and global power. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Imperial Propaganda: Colosseum games showcased imperial power, legitimizing Roman rule through public spectacle and entertainment

- Political Control: Emperors used games to distract citizens, maintain loyalty, and suppress dissent during political unrest

- Social Hierarchy: Seating arrangements reflected political status, reinforcing class divisions and elite dominance

- Political Alliances: Hosting games strengthened ties with provincial leaders, consolidating Roman political influence

- Public Approval: Emperors gained popularity by funding games, securing political support and stability

Imperial Propaganda: Colosseum games showcased imperial power, legitimizing Roman rule through public spectacle and entertainment

The Colosseum, a monumental amphitheater in the heart of Rome, served as more than just a venue for gladiatorial combat and public spectacles; it was a powerful tool of imperial propaganda. Through its games, the Roman Empire showcased its might, generosity, and legitimacy, reinforcing the social contract between rulers and the ruled. The sheer scale of the Colosseum—capable of seating 50,000 to 80,000 spectators—was a physical manifestation of imperial ambition and control. By hosting lavish games, emperors like Vespasian and Titus, who commissioned and inaugurated the Colosseum, sought to distract, entertain, and ultimately pacify the masses, ensuring their loyalty and acceptance of Roman rule.

Consider the logistics of the games: exotic animals from conquered territories were displayed in hunts (*venationes*), gladiators fought to the death, and mock naval battles (*naumachiae*) were staged in flooded arenas. These spectacles were not merely entertainment but deliberate demonstrations of Rome’s dominance over nature, its enemies, and even death itself. For instance, the inaugural games under Titus in 80 CE lasted 100 days, featuring thousands of gladiators and animals. Such extravagance was a calculated move to project imperial generosity and power, as emperors often funded these events from their own treasuries or war spoils, reinforcing the narrative of their benevolence and strength.

Analyzing the political function of these games reveals a sophisticated strategy. By providing free entertainment, emperors addressed the economic and social anxieties of the plebeians, who constituted the majority of the population. The distribution of food (*panem*) alongside the games (*circenses*)—a practice known as *panem et circenses*—was a form of welfare that kept the populace content and less likely to revolt. This system was not just about distraction but about creating a sense of obligation and gratitude toward the ruling class. The Colosseum, therefore, became a symbol of the empire’s ability to provide for its people while simultaneously asserting its authority.

A comparative perspective highlights the uniqueness of the Colosseum’s role in political legitimization. Unlike other ancient civilizations, Rome institutionalized public spectacle as a cornerstone of governance. While the Egyptians built pyramids to deify their pharaohs and the Greeks celebrated athletic prowess in the Olympics, the Romans used mass entertainment to foster unity and obedience. The Colosseum’s games were not isolated events but part of a broader cultural and political ecosystem that included triumphal processions, public feasts, and religious ceremonies. This integration ensured that imperial power was not just feared but also celebrated and internalized by the populace.

In practical terms, the Colosseum’s role as a propaganda machine offers lessons for modern political strategies. Leaders today often use public events—parades, rallies, or televised spectacles—to consolidate power and shape public opinion. However, the Roman approach was more direct and immersive, engaging citizens in a shared experience that reinforced their place within the imperial order. For contemporary policymakers, the takeaway is clear: public spectacle can be a potent tool for legitimizing authority, but its effectiveness depends on its ability to resonate with the needs and emotions of the audience. The Colosseum’s enduring legacy lies not just in its architectural grandeur but in its demonstration of how entertainment can be weaponized to sustain an empire.

Blackout Tuesday: A Political Statement or Social Awareness Movement?

You may want to see also

Political Control: Emperors used games to distract citizens, maintain loyalty, and suppress dissent during political unrest

The Colosseum, a marvel of ancient engineering, was more than an arena for gladiatorial combat—it was a tool of political control. Emperors understood that bread and circuses could pacify the masses, and the games provided a spectacle that distracted citizens from Rome’s political and economic troubles. By offering free entertainment, rulers shifted public focus away from grievances like taxation, corruption, or military failures, ensuring their authority remained unchallenged. This strategy was so effective that even during times of famine or war, the games continued, a testament to their role in maintaining social order.

Consider the mechanics of this control: the games were not merely random events but carefully orchestrated displays of imperial power. Emperors often funded the games themselves, earning the title of *editor* (producer) and directly linking the spectacle to their generosity. The sheer scale of the Colosseum, holding up to 50,000 spectators, ensured that a significant portion of Rome’s population was engaged and entertained. By controlling the narrative through these events, emperors fostered a sense of loyalty, positioning themselves as benefactors rather than oppressors. This psychological manipulation was a cornerstone of Roman political stability.

However, the games also served a darker purpose: suppressing dissent. Public executions and brutal contests were not just entertainment but warnings. Gladiators, often slaves or prisoners of war, fought to the death, a stark reminder of the consequences of defiance. Similarly, animal hunts and mock naval battles showcased imperial might, reinforcing the idea that Rome’s power was absolute. During periods of unrest, the games were intensified, acting as a safety valve for discontent and preventing rebellion. This dual function—distraction and intimidation—made the Colosseum a symbol of both unity and fear.

To implement such a strategy today, modern leaders could draw parallels by investing in public events that foster national pride while diverting attention from contentious issues. For instance, hosting large-scale cultural festivals or sporting events can unite communities and reduce political tension. However, caution must be exercised to avoid exploitation; transparency in funding and purpose is essential to prevent accusations of manipulation. The Colosseum’s legacy reminds us that while entertainment can be a powerful tool, its use must be balanced with genuine governance to avoid becoming a mere spectacle of control.

Is 'Freshman' Politically Incorrect? Exploring Gender-Neutral Alternatives

You may want to see also

Social Hierarchy: Seating arrangements reflected political status, reinforcing class divisions and elite dominance

The Colosseum’s seating chart was a microcosm of Roman society, a stone-carved manifesto of social order. Divided into five tiers, each level was strictly allocated to specific classes: senators in the front rows, closest to the spectacle; knights behind them; then plebeians, and finally, at the very top, women and slaves. This vertical stratification mirrored the rigid hierarchy of Rome, ensuring that even in leisure, the elite’s dominance was unchallenged. The arrangement wasn’t just practical—it was political, a daily reminder of one’s place in the empire.

Consider the logistics: the Colosseum held up to 50,000 spectators, yet its design prevented chaos. Entry was controlled by numbered entrances (*vomitoria*) corresponding to seating sections, a system so efficient it cleared the arena in minutes. For the elite, this meant more than convenience—it reinforced their privilege. Senators, for instance, had reserved marble seats (*sellae*) with optimal views, while the lower classes stood or sat on wooden benches. This spatial segregation wasn’t accidental; it was a deliberate tool to maintain order and assert the ruling class’s authority.

To understand the impact, imagine attending a gladiatorial event as a plebeian. Your view is obstructed, your comfort minimal, yet the spectacle is free—a calculated concession by the emperors to keep the masses content. Meanwhile, the elite’s proximity to the action symbolized their closeness to power. This dynamic wasn’t just about visibility; it was about control. By dictating who saw what and from where, the Colosseum’s seating became a silent enforcer of class divisions, ensuring the lower classes remained both entertained and in their place.

Modern event planners could learn from this ancient strategy, though with a twist. While the Colosseum’s hierarchy was exclusionary, today’s venues can use tiered seating to enhance experience without reinforcing inequality. For example, premium seats could offer perks like early access or exclusive content, while ensuring all attendees have a clear view. The key is to balance differentiation with inclusivity, avoiding the Colosseum’s mistake of turning social stratification into a spectacle. After all, the goal should be engagement, not division.

In retrospect, the Colosseum’s seating wasn’t merely a functional design—it was a political statement. By embedding hierarchy into architecture, Rome’s leaders ensured their dominance was as immovable as the arena’s stone walls. For contemporary societies, this serves as a cautionary tale: spatial arrangements aren’t neutral. They shape behavior, reinforce norms, and can either entrench inequality or foster unity. The next time you attend a large event, take a moment to observe the seating. It might reveal more about the organizers’ values than any speech ever could.

The Power of Polite Speech: Unlocking Social Harmony and Respect

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Political Alliances: Hosting games strengthened ties with provincial leaders, consolidating Roman political influence

The Colosseum, a marvel of ancient engineering, served as more than just an arena for gladiatorial combat; it was a strategic tool for fostering political alliances. By hosting games, the Roman Empire solidified its relationships with provincial leaders, ensuring their loyalty and extending its influence across vast territories. This practice was not merely entertainment but a calculated political maneuver designed to maintain unity and control.

Consider the logistics: provincial leaders were often invited to Rome to witness the games, where they were treated as honored guests. This gesture of inclusion reinforced their status within the empire while subtly reminding them of Rome’s power and generosity. The games themselves, featuring exotic animals and skilled gladiators, showcased Rome’s wealth and organizational prowess, leaving a lasting impression on these leaders. Such displays were not accidental; they were meticulously planned to inspire awe and loyalty, ensuring that provincial elites remained aligned with Roman interests.

To understand the impact, examine the frequency and scale of these events. The Colosseum hosted games for over four centuries, with some spectacles lasting up to 100 days and attracting crowds of 50,000 to 80,000 spectators. Provincial leaders, often governing distant regions, were brought into the heart of the empire, where they could witness firsthand the grandeur of Roman culture. This immersion was a powerful tool for integration, as it fostered a shared identity and dependence on Roman authority. By participating in these events, provincial leaders became stakeholders in the empire’s success, making rebellion or dissent less appealing.

A cautionary note: while the games strengthened alliances, they also had the potential to backfire if not managed carefully. Over-reliance on such displays could be perceived as bribery or manipulation, risking resentment among provincial leaders. Additionally, the immense cost of hosting games—estimated to consume up to 5% of the empire’s annual revenue—could strain resources, potentially weakening Rome’s ability to address other critical needs. Balancing spectacle with substance was crucial to ensuring the long-term effectiveness of this strategy.

In conclusion, the Colosseum’s role in hosting games was a masterclass in political diplomacy. By inviting provincial leaders to partake in these grand events, Rome not only entertained but also educated and integrated them into its political fabric. This approach, while resource-intensive, proved instrumental in consolidating Roman influence and maintaining the empire’s vast network of alliances. For modern leaders, this historical example underscores the value of cultural and social events as tools for building and sustaining political relationships.

Mastering Polite Payment Collection: Tips for Professional and Effective Communication

You may want to see also

Public Approval: Emperors gained popularity by funding games, securing political support and stability

The Colosseum, a marvel of ancient engineering, served as more than just an arena for gladiatorial combat; it was a political tool wielded by Roman emperors to solidify their power. By funding games and spectacles, emperors directly tapped into the public’s desire for entertainment, fostering loyalty and approval. This strategy was not merely about generosity—it was a calculated move to ensure political stability. The games provided a distraction from societal issues, while the emperor’s role as benefactor reinforced his image as a benevolent ruler. For instance, Emperor Titus inaugurated the Colosseum in 80 AD with 100 days of games, a move that cemented his popularity and legitimized his rule after the tumultuous reign of his father, Vespasian.

To understand the mechanics of this strategy, consider the psychological impact of public spectacles. The games were a rare opportunity for citizens of all social classes to gather and share in a communal experience. By sponsoring these events, emperors positioned themselves as providers of joy and unity, effectively bridging social divides. This was particularly crucial in Rome, where political factions and class tensions often simmered beneath the surface. The Colosseum became a stage for emperors to demonstrate their generosity and power, ensuring that their names were synonymous with prosperity and entertainment.

However, this approach was not without risks. The frequency and scale of the games required immense resources, straining the empire’s finances. Emperors had to balance the public’s insatiable demand for spectacles with the practicalities of governance. For example, Trajan, known for his military campaigns, also hosted lavish games to celebrate his victories, but such events were strategically timed to coincide with moments of triumph, maximizing their political impact. Over-reliance on this tactic could lead to economic instability, yet underutilization risked losing public favor.

A practical takeaway for modern leaders lies in the Colosseum’s lesson: public approval is often tied to visible acts of generosity and shared experiences. While the scale of Roman games is unmatched today, the principle remains relevant. Leaders can secure support by investing in public events, cultural initiatives, or infrastructure projects that resonate with their constituents. The key is to align these efforts with moments of collective significance, ensuring they are perceived as acts of unity rather than mere political theater.

In conclusion, the Colosseum’s role in Roman politics highlights the enduring connection between public entertainment and political stability. Emperors who mastered this dynamic gained not only popularity but also the loyalty needed to navigate the complexities of ruling an empire. By studying this historical precedent, contemporary leaders can glean insights into the art of securing public approval through strategic investment in communal experiences.

Unveiling the Hidden Mechanisms: How Politics Really Works Behind the Scenes

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Colosseum symbolized the might and generosity of the Roman Empire. Built by Emperor Vespasian and completed by his son Titus, it served as a gift to the Roman people, showcasing imperial wealth and reinforcing the emperor's authority through public entertainment.

The Colosseum was a tool for political control and social cohesion. By providing free games and spectacles, emperors distracted the populace from political issues, reduced social tensions, and fostered loyalty to the ruling regime.

The Colosseum strengthened the bond between emperors and citizens by demonstrating imperial benevolence. Emperors often hosted games to celebrate military victories or anniversaries, reinforcing their image as benefactors and ensuring popular support.

Yes, the Colosseum was a key venue for political propaganda. Events held there often glorified Roman values, military triumphs, and the emperor's rule, while also serving as a stage to display the empire's dominance and cultural superiority.

![Austin Powers Triple Feature (International Man of Mystery / The Spy Who Shagged Me / Goldmember) [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/91YNHjASr0L._AC_UY218_.jpg)