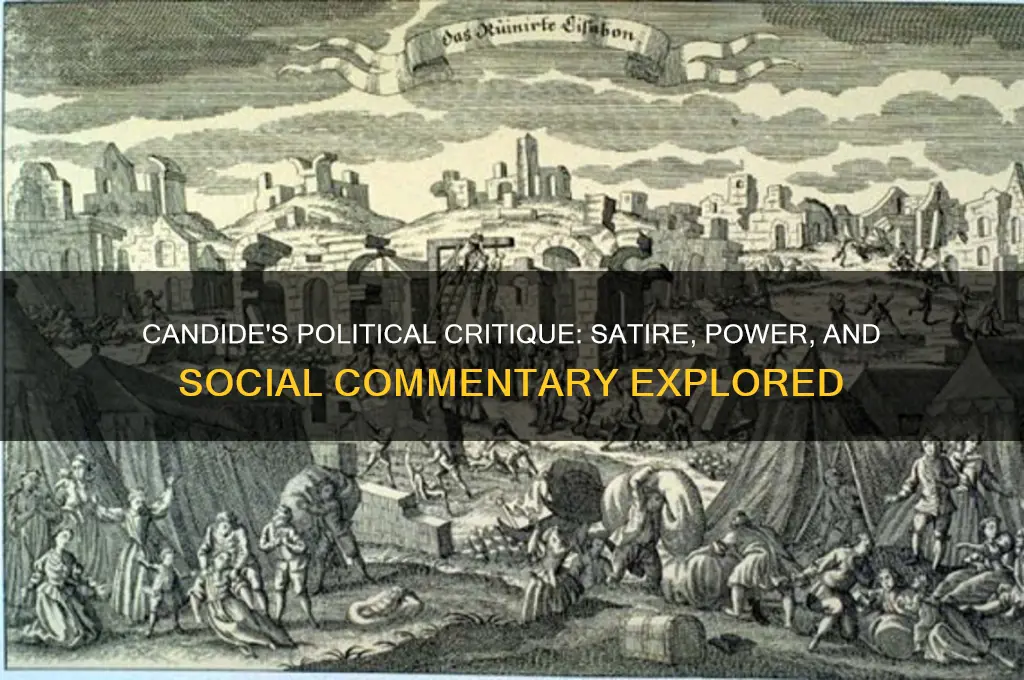

Voltaire's *Candide* is a scathing political satire that critiques the philosophical, social, and political ideologies of the 18th century. Through the protagonist's journey, Voltaire targets the optimism of thinkers like Leibniz, who argued that this is the best of all possible worlds, by exposing the absurdities and injustices of war, colonialism, religious hypocrisy, and class inequality. The novel’s portrayal of exploitation in the New World, the brutality of European powers, and the corruption of institutions like the Church and monarchy serves as a direct political commentary on the Enlightenment era’s failures and the need for critical reason over blind optimism. By weaving political critique into a narrative of absurdity and suffering, *Candide* remains a timeless indictment of power structures and ideological complacency.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Critique of Optimism | Satirizes the philosophical optimism of Leibniz, exposing its flaws in the face of human suffering and injustice. |

| Political Satire | Mocks European powers, colonialism, and religious institutions through exaggerated and absurd scenarios. |

| War and Violence | Highlights the futility and brutality of war, particularly through Candide's experiences in the Seven Years' War. |

| Religious Hypocrisy | Exposes the corruption and moral failings of religious figures and institutions, such as the Grand Inquisitor. |

| Colonialism and Exploitation | Critiques the exploitation of indigenous peoples and the economic greed of colonial powers. |

| Social Inequality | Portrays the rigid class system and the suffering of the lower classes, emphasizing the lack of social mobility. |

| Freedom and Autonomy | Advocates for individual freedom and self-reliance, as seen in Candide's final resolution to "cultivate our garden." |

| Global Perspective | Uses Candide's travels across continents to critique global political and social systems, including Europe, South America, and Asia. |

| Moral Relativism | Questions absolute moral truths by depicting diverse cultures and their varying ethical norms. |

| Critique of Enlightenment | While part of the Enlightenment, the novel also critiques its overconfidence in reason and progress. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Voltaire's critique of optimism and its political implications in absolute monarchies

- Satire of European colonialism and exploitation in Candide's global journeys

- Criticism of religious hypocrisy and its role in political power structures

- Depiction of war's horrors as a political statement against militarism

- Exploration of social inequality and the failures of feudal systems

Voltaire's critique of optimism and its political implications in absolute monarchies

Voltaire's *Candide* is a scathing critique of the philosophical optimism that dominated Enlightenment thought, particularly its political implications within absolute monarchies. By satirizing the idea that "all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds," Voltaire exposes the dangers of unquestioned belief in divine providence, which often served to justify the injustices and inequalities perpetuated by authoritarian regimes. Through Candide's journey, Voltaire illustrates how optimism, when applied to political systems, can blind individuals to the suffering caused by absolute power, effectively silencing dissent and maintaining the status quo.

Consider the character of Pangloss, whose unwavering optimism mirrors the intellectual elites who defended absolute monarchies. Pangloss’s mantra, "tout est bien" ("all is well"), echoes the rhetoric of court philosophers who argued that monarchs ruled by divine right and that any challenge to their authority was an affront to natural order. Voltaire’s critique here is twofold: first, he highlights the absurdity of such beliefs in the face of tangible human suffering, as exemplified by the Lisbon earthquake and Candide’s numerous misfortunes. Second, he reveals how this brand of optimism functions as a political tool, absolving rulers of responsibility for their actions and discouraging citizens from seeking change.

To understand the political implications, examine how absolute monarchies relied on a similar ideology to maintain control. In France, for instance, the monarchy was propped up by the notion of the "divine right of kings," a belief system that Voltaire’s critique directly undermines. By ridiculing the idea that every event, no matter how catastrophic, serves a greater purpose, Voltaire challenges the theological and philosophical foundations that legitimized absolute rule. This is not merely an intellectual exercise; it is a call to recognize the human cost of such systems, where power is concentrated in the hands of a few, often at the expense of the many.

A practical takeaway from Voltaire’s critique is the importance of critical thinking in political discourse. In absolute monarchies, optimism served as a form of intellectual anesthesia, numbing the populace to the realities of oppression. Voltaire’s work encourages readers to question authority, reject complacency, and demand accountability from those in power. For modern readers, this translates into a caution against accepting simplistic explanations for complex political issues, whether they come from leaders, media, or even well-intentioned philosophers.

Finally, Voltaire’s critique of optimism in *Candide* serves as a timeless reminder of the dangers of ideological rigidity in politics. By exposing the flaws in the belief that suffering is inherently meaningful or justified, he invites readers to confront the moral and political consequences of such thinking. In absolute monarchies, this optimism was not just a philosophical stance but a political strategy, one that Voltaire dismantles with wit and precision. His work remains a powerful tool for those seeking to challenge unjust systems, urging us to replace blind optimism with informed, compassionate action.

Political Landscapes: How Policies and Elections Influence Investor Confidence

You may want to see also

Satire of European colonialism and exploitation in Candide's global journeys

Voltaire's *Candide* is a scathing critique of European colonialism, using the protagonist's global journeys to expose the exploitation, hypocrisy, and brutality inherent in imperial expansion. Through Candide’s encounters in South America, the colonies, and beyond, Voltaire dismantles the myth of the "civilizing mission" by portraying colonizers as greedy, violent, and morally bankrupt. The novel’s satirical lens reveals how colonialism operates not as a force for progress but as a system of theft, enslavement, and cultural destruction.

Consider the episode in Paraguay, where Candide witnesses the Jesuit priests’ oppressive control over indigenous lands and resources. Voltaire highlights the irony of religious institutions justifying their dominance under the guise of spiritual salvation while exploiting the very people they claim to protect. The Jesuits’ wealth, amassed through forced labor and land seizure, underscores the economic motivations driving colonialism. This critique is not subtle; it is a direct indictment of the European powers and religious orders that profited from the subjugation of non-European peoples.

Candide’s journey to El Dorado offers a stark contrast, presenting an idealized society untouched by European influence. Here, Voltaire employs utopian imagery to critique the corruption of colonial societies. El Dorado’s prosperity, based on equality and mutual respect, exposes the flaws of European systems built on inequality and exploitation. However, Candide’s inability to remain in this paradise mirrors the inevitability of colonial encroachment, suggesting that no society is safe from the destructive reach of imperial ambition.

The novel’s portrayal of the slave trade in Surinam further amplifies its anti-colonial message. Candide encounters a slave whose hand has been mutilated by colonial overseers, a visceral depiction of the dehumanization inherent in the colonial economy. Voltaire’s description of this scene forces readers to confront the physical and moral costs of colonialism, challenging the era’s complacency toward such atrocities. By humanizing the victims of exploitation, Voltaire shifts the narrative from abstract economic gain to the tangible suffering of individuals.

In conclusion, *Candide*’s global journeys serve as a relentless exposé of European colonialism’s moral and ethical failures. Through satire, Voltaire reveals the system’s foundational violence, greed, and hypocrisy, urging readers to question the narratives of progress and enlightenment that justified imperial expansion. The novel remains a powerful reminder of the enduring consequences of exploitation and the necessity of critical scrutiny of power structures.

Where to Stream Polite Society: A Comprehensive Guide for Viewers

You may want to see also

Criticism of religious hypocrisy and its role in political power structures

Religious institutions in Voltaire's *Candide* are not mere backdrops but active players in a political theater of exploitation. The Grand Inquisitor, for instance, wields his authority not to uphold spiritual doctrine but to consolidate power, ordering Candide's flogging and the auto-da-fé not for heresy but to maintain control. This portrayal mirrors historical critiques of the Catholic Church's role in state affairs, where religious leaders often acted as de facto politicians, using dogma to justify political dominance. By depicting such figures as corrupt and self-serving, Voltaire exposes how religious hypocrisy becomes a tool for political oppression, stripping institutions of their moral high ground.

Consider the steps by which religious hypocrisy intertwines with political power: first, institutions claim divine authority, then they enforce compliance through fear or coercion, and finally, they align with ruling elites to suppress dissent. In *Candide*, the Jesuits in Paraguay exemplify this process, exploiting indigenous populations under the guise of missionary work while amassing wealth and influence. This pattern is not confined to fiction; historically, the Church's involvement in the Crusades, the Inquisition, and colonial ventures demonstrates how religious rhetoric can mask political and economic agendas. Recognizing this mechanism allows readers to dissect contemporary power structures where religious leaders or organizations may similarly cloak self-interest in piety.

A persuasive argument against religious hypocrisy in politics lies in its corrosive effect on public trust. When religious leaders prioritize power over principle, they undermine the very values they claim to uphold, alienating followers and fostering cynicism. Voltaire’s portrayal of the Anabaptist’s brother, who is kind and selfless despite his poverty, contrasts sharply with the wealthy, indifferent clergy. This juxtaposition highlights the moral bankruptcy of hypocritical religious figures, suggesting that true virtue lies outside institutional religion. For modern readers, this serves as a caution: when religious rhetoric aligns too closely with political expediency, it risks becoming a facade for manipulation rather than a force for good.

Comparatively, *Candide*’s critique of religious hypocrisy is both timeless and context-specific. While Voltaire targeted the Catholic Church’s dominance in 18th-century Europe, his observations resonate in any era where religion and politics intersect. For example, the novel’s depiction of religious leaders justifying suffering as part of God’s plan parallels modern debates about faith-based policies on issues like poverty or healthcare. By analyzing these parallels, readers can identify recurring patterns of hypocrisy and challenge them effectively. A practical takeaway is to scrutinize the motives behind religious political involvement, ensuring that faith serves the common good rather than narrow interests.

Descriptively, the auto-da-fé scene encapsulates the fusion of religious spectacle and political theater. The elaborate ceremony, complete with processions and public punishment, is less about spiritual purification than about demonstrating authority. Voltaire’s satirical tone underscores the absurdity of such displays, revealing how religious rituals can be weaponized to intimidate and control. This scene serves as a microcosm of larger political systems where symbolism and pageantry obscure exploitation. For those seeking to dismantle such structures, the lesson is clear: expose the performance, question the motives, and demand accountability from those who cloak power in piety.

Do Principals Teach Politeness? Exploring School Leaders' Role in Etiquette

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Depiction of war's horrors as a political statement against militarism

Voltaire's *Candide* employs vivid depictions of war's horrors to deliver a scathing critique of militarism, exposing its glorification as a dangerous illusion. Through the lens of Candide's journey, readers witness the brutal realities of conflict: mass slaughter, senseless violence, and the destruction of entire communities. The Seven Years' War, a contemporary event during Voltaire's time, serves as a backdrop, allowing him to satirize the absurdity of nations waging war over trivial territorial disputes while ordinary people suffer. The novel's graphic descriptions of battlefields strewn with corpses and soldiers maimed beyond recognition force readers to confront the human cost of militaristic ambitions.

Consider the scene where Candide and his companions stumble upon a village ravaged by war. The once-thriving community lies in ruins, its inhabitants either dead or dying. This tableau, devoid of heroism or glory, starkly contrasts with the romanticized narratives of war often propagated by those in power. Voltaire's choice to include such scenes is deliberate: by humanizing the victims of war, he dismantles the dehumanizing rhetoric that justifies militarism. The reader is compelled to question the morality of systems that prioritize conquest over compassion and destruction over diplomacy.

To fully grasp Voltaire's political statement, one must analyze the juxtaposition of war's brutality with the philosophical optimism espoused by characters like Pangloss. Pangloss's repeated mantra, "all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds," becomes increasingly absurd as the narrative unfolds. This irony highlights the disconnect between abstract ideologies that justify war and the tangible suffering it inflicts. Voltaire's critique extends beyond the battlefield, targeting the intellectual and political elites who perpetuate militarism under the guise of progress or divine will.

For those seeking to understand *Candide* as a political text, a practical exercise is to compare its depictions of war with historical accounts of the Seven Years' War. Examine primary sources such as soldier diaries or contemporary news reports to identify parallels with Voltaire's narrative. This exercise underscores the novel's grounding in reality, reinforcing its role as a political statement rather than mere fiction. Additionally, discussing *Candide* in the context of modern militarism can illuminate its enduring relevance, as the novel's critique of war's horrors remains applicable to contemporary conflicts.

Ultimately, *Candide*’s portrayal of war serves as a timeless warning against the perils of militarism. By forcing readers to confront the human cost of conflict, Voltaire challenges the ideologies that sustain it. The novel’s political power lies not only in its critique of war but also in its call for empathy and rationality in the face of senseless violence. As a guide to understanding the intersection of literature and politics, *Candide* remains an essential text for those seeking to question the systems that perpetuate suffering in the name of power.

Urban Planning and Politics: Navigating the Intersection of Power and Design

You may want to see also

Exploration of social inequality and the failures of feudal systems

Voltaire's *Candide* serves as a scathing critique of social inequality, exposing the rigid hierarchies of feudal systems that perpetuate injustice. Through the lens of Candide’s journey, readers witness the stark disparities between the privileged elite and the oppressed masses. For instance, the Baron’s family embodies the arrogance and entitlement of the aristocracy, while characters like Cunégonde and the Old Woman endure suffering as a direct result of their lower status. This contrast highlights how feudalism traps individuals in predetermined roles, denying them agency and dignity. By portraying such inequalities, Voltaire forces readers to question the morality of a system that thrives on exploitation.

To understand the failures of feudalism in *Candide*, consider the practical implications of its rigid class structure. In feudal societies, social mobility was nearly impossible, and individuals were bound to their birthright roles—whether as lords, peasants, or serfs. Voltaire illustrates this through the Baron’s insistence on noble lineage, even in the face of absurdity, such as his refusal to marry Cunégonde to Candide due to a perceived lack of noble ancestry. This inflexibility not only stifles personal growth but also perpetuates cycles of poverty and oppression. For those seeking to analyze feudal systems critically, *Candide* offers a vivid reminder of how such structures inherently favor the few at the expense of the many.

A persuasive argument against feudalism emerges from Voltaire’s depiction of its inefficiency and cruelty. The novel’s portrayal of war, slavery, and economic exploitation underscores how feudal systems fail to provide for the common good. For example, the Lisbon earthquake and the subsequent auto-da-fé reveal a society more concerned with religious dogma and class preservation than with human welfare. Similarly, the character Cacambo’s observation that “we must cultivate our garden” suggests a rejection of feudal dependency in favor of self-sufficiency and communal effort. This critique resonates with modern readers, as it parallels contemporary struggles against systemic inequality and the call for equitable resource distribution.

Comparatively, *Candide*’s exploration of social inequality invites reflection on the persistence of feudal remnants in modern societies. While feudalism as a formal system has largely disappeared, its legacy endures in structures like inherited wealth, class-based education, and systemic discrimination. Voltaire’s satire remains relevant, urging readers to identify and dismantle these vestiges. For instance, the novel’s critique of nobility’s unearned privilege mirrors today’s debates about meritocracy and the role of birthright in determining opportunity. By drawing this parallel, *Candide* encourages a proactive approach to addressing inequality, emphasizing the need for systemic change rather than mere reform.

In conclusion, *Candide*’s exploration of social inequality and the failures of feudal systems offers a timeless critique of unjust hierarchies. Through vivid characters and absurd scenarios, Voltaire exposes the moral and practical shortcomings of a system that prioritizes class over humanity. Readers are not only entertained but also challenged to examine their own societies for feudal remnants and to advocate for a more equitable world. This makes *Candide* not just a political satire but a call to action for those committed to justice and equality.

Does Vonage Support Political Agendas? Uncovering the Truth Behind the Claims

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Candide satirizes various political systems, including absolute monarchy, colonialism, and religious theocracy, by exposing their corruption, inefficiency, and hypocrisy. Voltaire uses humor and exaggeration to highlight the flaws in these systems, advocating for reason and reform.

Candide portrays war as a senseless and destructive force driven by the ambitions of rulers, not the welfare of the people. Through scenes like the Battle of Kunersdorf, Voltaire criticizes the glorification of war and the abuse of power by political and military leaders.

Candide exposes the political manipulation of religion, particularly by the Catholic Church, to maintain control and justify oppression. Characters like the Grand Inquisitor and the Jesuit priests are depicted as corrupt and self-serving, using religion to further their political agendas.