Antarctica, the southernmost continent, is unique in its political definition, as it is not governed by any single country but is instead managed through an international treaty system. The Antarctic Treaty, signed in 1959, designates the continent as a demilitarized and nuclear-free zone, primarily reserved for peaceful scientific research. This treaty, ratified by over 50 countries, suspends all territorial claims made by nations prior to its signing, effectively placing Antarctica under a framework of shared responsibility and cooperation. The treaty system, supported by additional agreements like the Protocol on Environmental Protection, ensures that Antarctica remains a global commons, free from exploitation and conflict, while fostering international collaboration in scientific exploration and environmental preservation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Sovereignty Claims | Seven nations (Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway, and the United Kingdom) maintain territorial claims in Antarctica, but these claims are not universally recognized. |

| Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) | Established by the Antarctic Treaty (1959), which designates Antarctica as a demilitarized, nuclear-free zone dedicated to peace and scientific research. |

| Treaty Signatories | As of 2023, 54 countries are signatories to the Antarctic Treaty, including 29 Consultative Parties with voting rights and 25 Non-Consultative Parties. |

| Environmental Protection | The Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (Madrid Protocol, 1991) prohibits mining, designates Antarctica as a "natural reserve," and sets strict guidelines for human activities. |

| Governance Structure | No single government; managed through consensus-based decision-making by Consultative Parties at annual Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings (ATCM). |

| Freedom of Scientific Research | All signatories have the right to conduct scientific research in Antarctica, with a commitment to share data and findings internationally. |

| Demilitarization | Military activities, except for scientific research or peaceful purposes (e.g., logistics), are prohibited. |

| Inspections | Consultative Parties conduct inspections to ensure compliance with the Antarctic Treaty and its protocols. |

| Legal Framework | The ATS includes the Antarctic Treaty (1959), Madrid Protocol (1991), and other agreements addressing marine life, pollution, and liability. |

| International Cooperation | Antarctica is a model for international cooperation, with nations working together on scientific research, environmental protection, and logistical support. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Antarctic Treaty System: Framework governing international relations, ensuring peaceful use and scientific cooperation

- Territorial Claims: Seven nations assert sovereignty over sectors, though claims are largely unrecognized

- Condominium Governance: Joint management by treaty parties, no single authority controls the continent

- Demilitarized Zone: Bans military activities, mineral mining, and nuclear testing in Antarctica

- Environmental Protocol: Protects Antarctica as a natural reserve, prohibiting harmful human activities

Antarctic Treaty System: Framework governing international relations, ensuring peaceful use and scientific cooperation

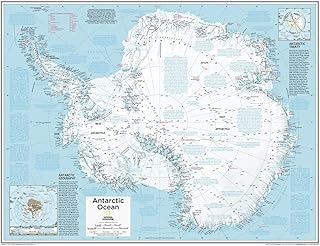

Antarctica, a continent devoid of indigenous inhabitants, is governed not by a single nation but by a unique international framework known as the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS). Established in 1959, the ATS is a cornerstone of global diplomacy, ensuring that this pristine environment remains a zone of peace and scientific collaboration. Unlike traditional territorial claims, the ATS prioritizes collective stewardship over individual sovereignty, setting a precedent for international cooperation in shared global commons.

At its core, the Antarctic Treaty System comprises the Antarctic Treaty, which designates the continent as a demilitarized and nuclear-free zone, and subsequent agreements like the Protocol on Environmental Protection. These instruments collectively prohibit military activities, mineral mining, and any actions that could harm the environment, while fostering scientific research. For instance, over 30 countries operate research stations in Antarctica, sharing data and resources to advance studies on climate change, biodiversity, and glaciology. This collaborative model ensures that scientific inquiry, rather than geopolitical rivalry, drives human activity on the continent.

One of the ATS’s most innovative features is its consultative meeting mechanism, where signatory nations with active research programs discuss and adopt measures to implement the treaty’s objectives. This process allows for adaptive governance, addressing emerging challenges such as tourism regulation, marine conservation, and the impact of climate change. For example, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), established under the ATS, manages fisheries to prevent over-exploitation, demonstrating how the system balances human activity with environmental preservation.

Critically, the ATS does not resolve territorial claims but instead freezes them, ensuring they cannot be asserted or expanded. This pragmatic approach has prevented conflicts among the seven claimant nations (Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway, and the United Kingdom) and allows non-claimant states to participate equally in decision-making. This neutrality underscores the ATS’s focus on shared values over competing interests, offering a model for managing other global challenges where cooperation is essential.

In practice, the ATS serves as a blueprint for international governance in areas beyond national jurisdiction. Its success lies in its ability to reconcile diverse national priorities under a common purpose: preserving Antarctica for the benefit of all humanity. For individuals and organizations engaging with the continent, adherence to ATS principles—such as environmental impact assessments for research projects or tourism operations—is mandatory. This ensures that human activities align with the treaty’s goals, safeguarding Antarctica’s unique status as a natural reserve devoted to peace and science.

Mastering Political Psychology: A Guide to Becoming a Political Psychologist

You may want to see also

Territorial Claims: Seven nations assert sovereignty over sectors, though claims are largely unrecognized

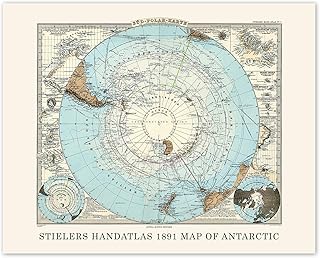

Antarctica, a continent devoid of indigenous inhabitants, has become a focal point for territorial claims by seven nations: Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway, and the United Kingdom. These countries assert sovereignty over specific sectors of the continent, often based on historical exploration, scientific presence, or geographic proximity. However, these claims are largely unrecognized internationally, creating a unique political landscape governed by the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS).

Consider the complexity of these claims through a comparative lens. Argentina, Chile, and the UK’s overlapping claims in the Antarctic Peninsula region exemplify the tension between national ambitions and international cooperation. While these nations maintain research stations and symbolic governance, the ATS suspends all sovereignty disputes, prioritizing scientific collaboration and environmental protection. This arrangement highlights a pragmatic approach: claims exist on paper but are functionally neutralized by treaty obligations.

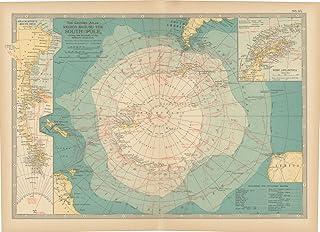

From an instructive perspective, understanding these claims requires examining their legal basis. Most claims stem from early 20th-century expeditions, such as Norway’s 1939 claim to Queen Maud Land or Australia’s 1933 claim to 42% of the continent. However, the 1959 Antarctic Treaty explicitly states that no new claims can be made, and existing claims are neither endorsed nor disputed. For practical purposes, this means that while nations may fly their flags at research stations, their authority is limited to logistical operations and does not extend to governance over the land itself.

A persuasive argument emerges when considering the environmental stakes. Antarctica’s pristine ecosystem and its role in global climate regulation demand a framework that transcends territorial ambitions. The ATS, with its prohibition on military activity and mineral exploitation, serves as a model for international stewardship. By deprioritizing unrecognized claims, the global community can focus on preserving Antarctica as a "common heritage of mankind," ensuring its resources and scientific potential benefit humanity collectively rather than individual nations.

Finally, a descriptive analysis reveals the symbolic nature of these claims. Nations often use their Antarctic presence to project geopolitical influence or national pride. For instance, Chile and Argentina’s overlapping claims reflect historical rivalries, while Australia’s vast sector underscores its regional aspirations. Yet, these assertions remain largely ceremonial, as the ATS mandates that all activities in Antarctica must be peaceful and cooperative. This duality—between formal claims and practical collaboration—defines the continent’s political identity, making it a unique case study in international relations.

Understanding the Complexities of British Politics: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Condominium Governance: Joint management by treaty parties, no single authority controls the continent

Antarctica’s political framework is a masterclass in shared responsibility, epitomized by the concept of condominium governance. Unlike traditional territories governed by a single authority, Antarctica is jointly managed by treaty parties under the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS). Signed in 1959, this treaty designates the continent as a demilitarized zone dedicated to peace and scientific research. No single nation claims sovereignty, and all signatories share decision-making power, ensuring no one dominates its governance. This model reflects a rare global consensus, prioritizing collaboration over competition in a region of immense environmental and strategic importance.

The mechanics of condominium governance in Antarctica are both structured and flexible. Treaty parties meet annually at the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings (ATCM) to discuss issues ranging from environmental protection to scientific cooperation. Decisions are made by consensus, requiring all parties to agree—a process that fosters dialogue but can also slow progress. For instance, the Protocol on Environmental Protection, adopted in 1991, bans mining and designates Antarctica as a "natural reserve" through unanimous agreement. This framework ensures that no single nation can unilaterally exploit the continent’s resources, safeguarding its pristine state.

One of the most compelling aspects of condominium governance is its ability to transcend geopolitical rivalries. During the Cold War, Antarctica remained a zone of cooperation even as tensions flared elsewhere. Today, this model serves as a blueprint for managing global commons, such as the high seas or outer space. However, challenges persist. As more nations join the ATS (currently 54 parties), reaching consensus becomes increasingly complex. Additionally, rising interest in Antarctica’s resources and strategic value tests the system’s resilience, requiring constant vigilance and adaptation.

Practical implementation of condominium governance relies on transparency and accountability. Treaty parties conduct inspections to ensure compliance with agreed-upon rules, such as restrictions on military activities and waste disposal. For example, the Environmental Protocol mandates that all stations minimize their ecological footprint, with regular audits to verify adherence. Scientists and support staff from different nations often work side by side, fostering a culture of mutual respect and shared purpose. This hands-on collaboration not only strengthens the governance model but also reinforces Antarctica’s role as a symbol of global unity.

In conclusion, condominium governance in Antarctica is a testament to what can be achieved when nations prioritize collective interests over individual gain. By eliminating the possibility of a single authority, the ATS ensures that decisions are made through dialogue and consensus, preserving the continent for future generations. While not without its challenges, this model offers valuable lessons for managing other shared global resources. As Antarctica continues to face pressures from climate change and human activity, the strength of its governance will be crucial in maintaining its status as a natural reserve and a beacon of international cooperation.

Is FactCheck.org Politically Biased? Uncovering the Truth Behind the Claims

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Demilitarized Zone: Bans military activities, mineral mining, and nuclear testing in Antarctica

Antarctica stands as a unique demilitarized zone, a continent where military activities, mineral mining, and nuclear testing are strictly prohibited. This status is enshrined in the Antarctic Treaty System, a framework of international agreements that collectively define Antarctica’s political and environmental safeguards. Signed in 1959 by 12 nations and now ratified by over 50, the treaty ensures that Antarctica remains a zone of peace and science, free from the geopolitical conflicts and resource exploitation that plague other regions.

The ban on military activities is absolute. No military installations, weapons testing, or maneuvers are permitted. This prohibition extends to the use of military personnel or equipment for any purpose other than scientific research or logistical support. For instance, while countries like the United States and Russia maintain research stations staffed by personnel with military backgrounds, their roles are strictly non-combative, focusing on tasks such as transportation and infrastructure maintenance. This demilitarization ensures that Antarctica remains a neutral ground, untouched by the strategic rivalries of the global powers.

Mineral mining is another activity explicitly forbidden under the Antarctic Treaty. Despite the continent’s estimated vast reserves of coal, iron, copper, and rare earth elements, the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (Madrid Protocol) bans all commercial resource extraction. This moratorium, in place since 1991, reflects a global consensus to prioritize environmental preservation over economic gain. While the protocol is set to be reviewed in 2048, current international sentiment strongly favors extending the ban, underscoring Antarctica’s role as a pristine natural reserve.

Nuclear testing and the disposal of radioactive waste are also strictly prohibited in Antarctica. This ban aligns with broader global efforts to curb nuclear proliferation and environmental contamination. The continent’s isolation and extreme conditions make it an ideal location for scientific studies on climate change, ozone depletion, and astrophysics, but these pursuits must never compromise its ecological integrity. For example, the Antarctic Treaty requires all scientific activities to undergo rigorous environmental impact assessments, ensuring that research does not inadvertently harm the continent’s fragile ecosystems.

In practice, enforcing these bans requires international cooperation and transparency. The Antarctic Treaty System mandates regular inspections of research stations and activities by signatory nations, fostering a culture of accountability. Violations, though rare, are met with diplomatic censure and corrective measures. This collective oversight ensures that Antarctica remains a demilitarized zone, free from exploitation and conflict, and serves as a model for global cooperation in preserving shared heritage. By safeguarding Antarctica from military, mining, and nuclear activities, the international community upholds its commitment to a continent dedicated to peace, science, and environmental stewardship.

Unveiling CNBC's Political Leanings: Fact or Fiction in Media Bias?

You may want to see also

Environmental Protocol: Protects Antarctica as a natural reserve, prohibiting harmful human activities

Antarctica, a continent devoid of indigenous human populations, is governed by a unique international treaty system. The Antarctic Treaty System (ATS), established in 1959, sets the framework for its political definition, emphasizing peaceful use and scientific cooperation. Within this system, the Environmental Protocol stands as a cornerstone, ensuring Antarctica remains a natural reserve dedicated to peace and science. Adopted in 1991, this protocol explicitly prohibits activities related to mineral resource exploitation and designates Antarctica as a "natural reserve, devoted to peace and science."

The Environmental Protocol is not merely symbolic; it imposes strict regulations on human activities. It bans mining, oil drilling, and any activity that could harm the environment. For instance, the protocol requires all waste to be removed from the continent, and even the introduction of non-native species is tightly controlled. This level of protection is unparalleled globally, making Antarctica a unique case study in international environmental governance. The protocol’s success lies in its comprehensive approach, addressing both immediate threats and long-term sustainability.

To understand its impact, consider the contrast with other regions. While the Arctic faces increasing industrial activity and territorial disputes, Antarctica remains largely untouched due to the Environmental Protocol. This is not to say enforcement is flawless; challenges arise from logistical difficulties and the need for unanimous agreement among treaty parties. However, the protocol’s existence has fostered a culture of compliance, with nations prioritizing environmental stewardship over exploitation. For example, when a proposal for Antarctic krill fishing quotas was debated, the protocol’s precautionary principle guided decisions to prevent over-harvesting.

Implementing the Environmental Protocol requires collaboration across scientific, governmental, and logistical domains. Researchers must adhere to strict guidelines, such as using biodegradable materials and maintaining safe distances from wildlife. Tour operators, whose activities have grown significantly, are subject to regulations like visitor limits and designated landing sites. These measures ensure human presence does not disrupt ecosystems. For instance, the protocol mandates that tour groups larger than 20 people split into smaller sub-groups to minimize impact.

The Environmental Protocol’s legacy is its ability to balance human curiosity with environmental preservation. It serves as a model for how international agreements can protect vulnerable ecosystems. While Antarctica’s remoteness aids in its protection, the protocol’s success underscores the importance of proactive, globally coordinated efforts. As climate change poses new threats, the protocol’s adaptability will be tested, but its foundation remains a testament to humanity’s capacity to prioritize the planet’s health over short-term gains.

Has Politics Monday Been Canceled? Exploring the Shift in Political Discourse

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, Antarctica is not a country. It is a continent governed by an international treaty, the Antarctic Treaty System, which ensures it remains a demilitarized and cooperative zone for scientific research.

Seven countries claim territorial sovereignty in Antarctica: Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway, and the United Kingdom. However, these claims are not universally recognized due to the Antarctic Treaty, which effectively freezes all territorial disputes.

The Antarctic Treaty (1959) designates Antarctica as a zone free from military activity, territorial claims, and political disputes. It promotes international cooperation, scientific research, and environmental protection, ensuring the continent is used exclusively for peaceful purposes.