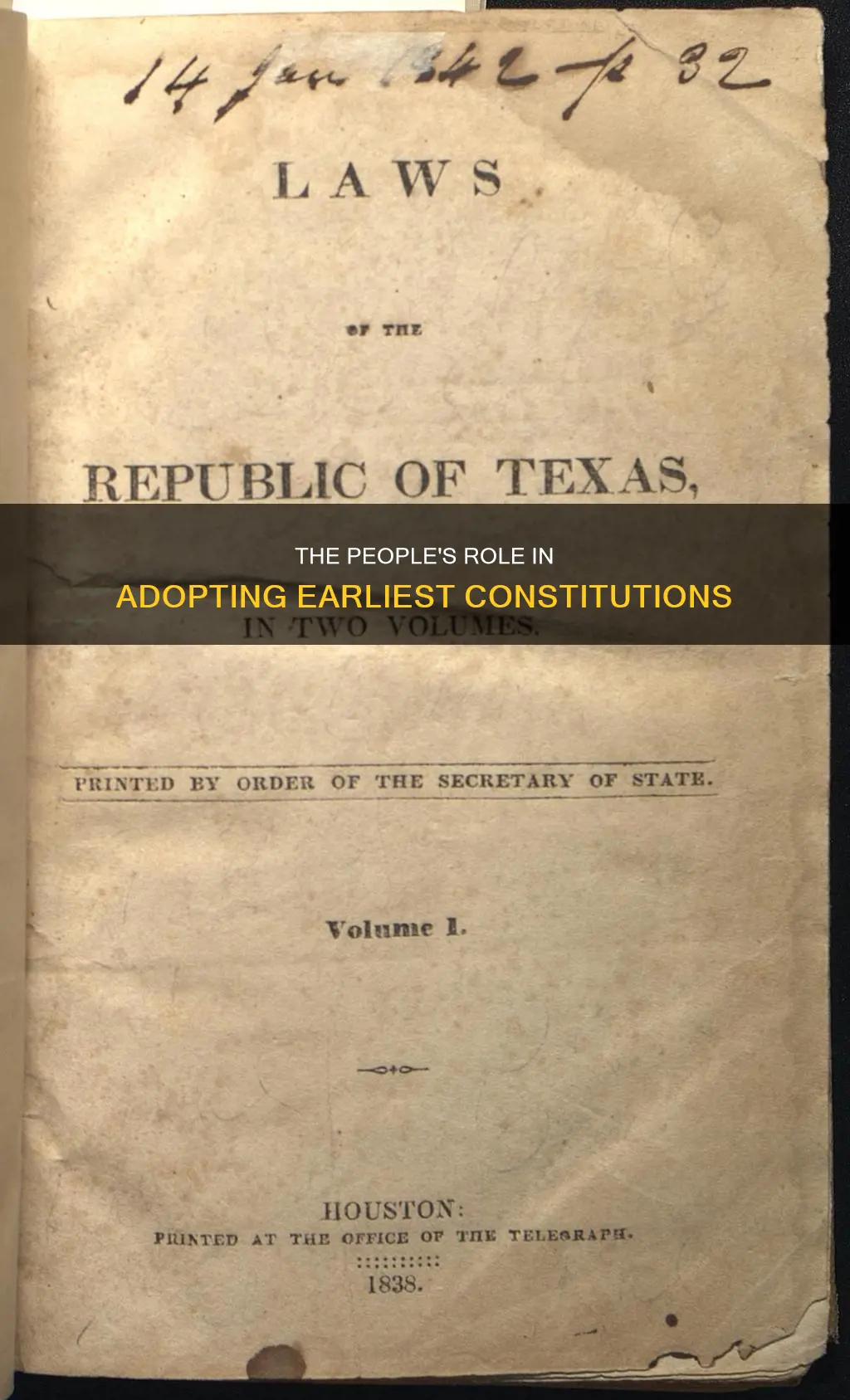

The adoption of the earliest constitutions was a complex process that involved a range of stakeholders, including political leaders, delegates, and the general public. In the case of the United States Constitution, the process began with the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787, where delegates debated and drafted the document behind closed doors. The final Constitution was signed by 38 delegates, representing 13 states, and included an introductory paragraph stating We the People, signifying the source of the government's legitimacy. The ratification process was challenging, with Federalists and Anti-Federalists holding opposing views. The Federalists, led by Madison, believed in a strong central government and worked to secure ratification through state conventions, bypassing state legislatures. The Anti-Federalists opposed the Constitution due to its similarities to the overthrown government and the lack of a bill of rights. The final vote in Maryland resulted in a Federalist victory, and the new government was formed. The people of the United States played a crucial role in embracing and legitimizing the government outlined in the Constitution. Similarly, the Kingdom of Sweden's adoption of the 1634 Instrument of Government and the Haudenosaunee nation's oral constitution, the Gayanashagowa, also involved the active participation and consensus of the people.

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

What You'll Learn

The role of Federalists and anti-Federalists

The earliest constitutions were adopted by various civilisations, including Germanic peoples, the Haudenosaunee nation, the Kingdom of Sweden, the Colony of Connecticut, and the British colonies in North America. The US Constitution, in particular, saw the involvement of Federalists and anti-Federalists, whose roles are described below.

The Federalists and anti-Federalists played significant and contrasting roles in the adoption of the US Constitution, with Federalists shaping the Constitution and campaigning for its ratification, while anti-Federalists opposed it due to concerns about centralisation of power and the absence of a bill of rights.

The Federalists, with their nationalist beliefs, were instrumental in shaping the US Constitution in 1787, advocating for a strong central government to address the nation's challenges. They argued that the existing Articles of Confederation, which gave the Confederation Congress rule-making and funding powers without enforcement, were inadequate. Led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and George Washington, they sought to redesign the government and strengthen the national government's authority.

The anti-Federalists, on the other hand, vehemently opposed the ratification of the Constitution. They believed that the Constitution's creation of a powerful central government resembled the monarchy they had recently overthrown and posed a threat to individual liberties. They argued that the liberties of the people were better safeguarded by state governments rather than a federal one. Additionally, they criticised the absence of a bill of rights to protect individual liberties and ensure that the federal government did not become tyrannous.

The anti-Federalists fought against ratification at every state convention, but they lacked effective organisation across the thirteen states. Their efforts were not entirely futile, as they successfully pressured the first Congress under the new Constitution to establish the Bill of Rights, which later became the first ten amendments to the Constitution.

The Federalist victory in Maryland, for instance, was celebrated with a parade featuring a 15-foot float called "Ship Federalist." The Federalists' success in ratifying the Constitution was due in part to their tactical decision to bypass state legislatures, where many state political leaders stood to lose power, and instead bring the issue before "the people" through special ratifying conventions in each state.

The Constitution: Ratification Objections and Their Impact

You may want to see also

The Great Compromise

The people were directly involved in adopting the earliest constitutions, with varying degrees of participation and influence. In the case of the United States Constitution, the process involved a Constitutional Convention, state conventions, and popular referendums.

To resolve this impasse, a "Grand Committee" or compromise committee was formed, consisting of one delegate from each state. The committee, which included Roger Sherman and Oliver Ellsworth from Connecticut, proposed a bicameral legislature, retaining the idea of two houses as proposed earlier by Edmund Randolph in the Virginia Plan. The Great Compromise dictated that the upper house or Senate would have equal representation among the states, with each state having two members, while the lower house or House of Representatives would have proportional representation, with one representative for every 30,000 or 40,000 inhabitants, including three-fifths of each state's enslaved population. Additionally, it was agreed that revenue and spending bills would originate in the lower house.

Benjamin Franklin's Constitutional Legacy: His Key Contributions

You may want to see also

The Three-Fifths Compromise

The compromise also had implications for taxation, as the same three-fifths ratio was used to determine the federal tax contribution required of each state. This increased the direct federal tax burden of slaveholding states. Additionally, the compromise granted slaveholding states the right to count three-fifths of their enslaved population when apportioning representatives to Congress, leading to their perpetual overrepresentation in national politics.

Constitutive Genes: Bacterial Regulation Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$81.23 $133

The ratification campaign

The Federalists needed to convert at least three states to ratify the Constitution, and they faced strong opposition from Anti-Federalists in key states such as Virginia, New York, and Massachusetts. The tide turned in Massachusetts, where the “vote now, amend later” compromise helped secure victory and eventually convinced the remaining holdouts. The Federalists also published a series of commentaries known as The Federalist Papers in support of ratification.

The campaign involved intense debates and compromises. One of the fiercest arguments was over congressional representation, with delegates compromising by agreeing to give each state one representative for every 30,000 people in the House of Representatives and two representatives in the Senate. They also agreed to count enslaved Africans as three-fifths of a person and allowed the slave trade to continue until 1808.

The delegates to the Constitutional Convention, including Madison, Hamilton, and Jay, played a crucial role in the ratification campaign. They persuaded members that the new constitution should be ratified by conventions of the people rather than the Congress or state legislatures. On September 17, 1787, 38 delegates signed the Constitution, with George Reed signing on behalf of John Dickinson of Delaware, bringing the total to 39 signatures.

Arizona Constitution: Judicial Branch Organization

You may want to see also

The vote now, amend later compromise

The people were highly involved in adopting the earliest constitutions, with their input being sought and, at times, contentious.

The earliest constitutions were adopted by the British colonies in North America that became the original 13 states of the US. This occurred in 1776 and 1777 during the American Revolution, with the exceptions of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts adopted its constitution in 1780, while Connecticut and Rhode Island continued to operate under their colonial charters until they adopted their first state constitutions in 1818 and 1843, respectively.

The creation of the US Constitution, on the other hand, was a lengthy and contentious process. The Constitutional Convention assembled in Philadelphia in May 1787, with delegates debating the Articles of Confederation and eventually deciding to redesign the government. One of the fiercest arguments was over congressional representation, with the framers compromising by giving each state one representative for every 30,000 people in the House of Representatives and two in the Senate. They also agreed to count enslaved Africans as three-fifths of a person, temporarily resolving the contentious issue of slavery.

The Anti-Federalists strongly opposed the Constitution due to its creation of a powerful central government and lack of a bill of rights. The Federalists, on the other hand, believed in a strong central government. The "vote now, amend later" compromise was crucial in securing victory in Massachusetts and the final holdout states, allowing for the enactment of the new government. The final vote on April 28, 1788, resulted in 63 votes for and 11 against.

The first 10 amendments to the Constitution, known as the Bill of Rights, were ratified by three-fourths of the states by December 15, 1791. James Madison played a significant role in shepherding these amendments through Congress, ensuring that the interests and views of both Federalists and Anti-Federalists were considered.

The earliest constitutions were shaped by the diverse interests and views of the people, with compromises being made to address contentious issues. The "vote now, amend later" compromise was a crucial tactic employed by the Federalists to secure the adoption of the US Constitution, demonstrating the people's direct involvement in the constitutional process.

Congress Members' Allegiance: Constitution or Personal Interests?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The first North American constitution was the Fundamental Orders, adopted by the Colony of Connecticut in 1639.

The first US constitution was the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, which was drafted in mid-June 1777 and adopted by the full Congress in mid-November of the same year. Ratification by the 13 colonies took over three years and was completed on March 1, 1781.

The Articles of Confederation gave the Confederation Congress the power to make rules and request funds from the states, but it had no enforcement powers, couldn’t regulate commerce, or print money.

The nationalists, led by Madison, believed that any new constitution should be ratified through conventions of the people and not by the Congress and the state legislatures. They wanted to bring the issue before "the people", where ratification was more likely. The Constitution was clear: it would only go into effect when nine of the thirteen states chose to ratify it.