Constitutive genes are genes that maintain the same level of expression and are also called housekeeping genes. Gene regulation is essential for an organism's versatility and adaptability. In bacteria, gene expression is controlled by transcription factors and the global physiology of the cell. The variation in gene expression across growth phases is influenced by both the physiological state of the cell and transcription factors. Transcription factors can act as repressors or activators, suppressing or enhancing gene transcription in response to external stimuli. The interplay between demand-frequency for a gene product, the genetic response rate, and fitness determines the optimal constitutive expression level. Environmental and intracellular noise favour a responsive strategy, reducing the fitness of a constitutive strategy.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Constitutive genes are those that have the same level of expression. They are also called housekeeping genes. |

| Example | Ribosomal RNA involving protein synthesis |

| Gene Regulation | Gene regulation is useful for the versatility and adaptability of an organism. |

| Regulation in Bacteria | Regulation of transcription in bacteria involves binding to DNA near a promoter to affect the transcription of nearby genes. |

| Responsive vs. Constitutive Expression | Environmental and intracellular noise favor the responsive strategy, while reducing the fitness of the constitutive strategy. |

| Optimal Expression Level | The optimal constitutive expression level depends on how costs and benefits increase with the expression level. |

| Repressible Operons | Operons for catabolism are often repressible. Genes are turned off unless the appropriate substance is available. |

| Repressible Anabolism | When enough of the product is present, genes are turned off to prevent overproduction. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Constitutive genes are those with the same level of expression

- Gene regulation is useful for adaptability and versatility

- Transcription factors and global physiology of the cell control gene expression

- The variation of gene expression is influenced by growth phases

- Environmental factors determine the optimal constitutive expression levels

Constitutive genes are those with the same level of expression

Constitutive genes are those that maintain a constant level of expression. They are also referred to as "housekeeping genes". An example of a constitutive gene is ribosomal RNA, which plays a role in protein synthesis. Gene regulation is essential for an organism's versatility and adaptability.

Gene expression can be classified as either constitutive or responsive. While constitutive genes maintain a constant level of expression, responsive genes can be influenced by environmental factors and intracellular conditions. These factors include the availability of specific nutrients, temperature fluctuations, salt content, and the presence of toxins or antibiotics.

The choice between constitutive and responsive gene expression strategies depends on the specific conditions and demands faced by an organism. In a changing environment, the optimal constitutive expression level may differ from the average demand for the gene product. This implies that constitutive expression must be carefully regulated to balance the costs and benefits associated with different expression levels.

Studies have compared the fitness of constitutive and responsive expression strategies. Interestingly, it has been found that constitutive expression can provide higher fitness than responsive expression, even when the regulatory machinery is cost-free. This suggests that constitutive expression may offer advantages in certain environments or under specific conditions.

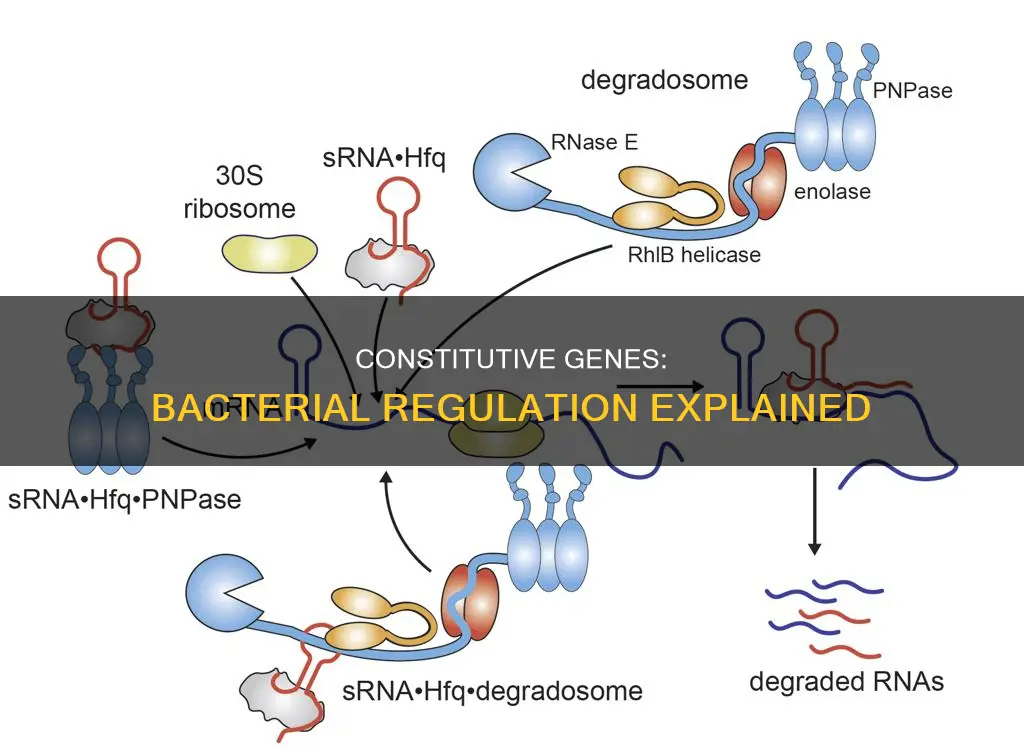

Regulation of transcription in bacteria involves binding to DNA near a promoter region, influencing the transcription of nearby genes. This process can be further categorized into positive and negative regulation, depending on whether it increases or decreases the rate of transcription, respectively.

Married Couples and Family Definition: Children Necessary?

You may want to see also

Gene regulation is useful for adaptability and versatility

Gene regulation is an important mechanism that allows bacteria to adapt to changing environments and exhibit metabolic versatility. It is a complex process involving the interplay of various regulatory mechanisms and signals. By regulating gene expression, bacteria can efficiently manage their energy and metabolic responses, ensuring their survival and adaptability.

Gene regulation in bacteria is a tightly controlled process involving multiple mechanisms operating at different levels and stages of gene expression. It is influenced by a combination of factors, including transcription, translation, initiation, elongation, and termination. The expression of a single bacterial gene or operon is often controlled by a diverse set of mechanisms, adding to the complexity and versatility of bacterial regulatory systems.

One example of gene regulation in bacteria is the competition for binding to the limited pool of core RNAP molecules. This competition constitutes a form of gene regulation, facilitating cross-talk between different classes of genes. Bacteria possess alternative σ factors that recognize specific promoter sequences and compete for binding to RNAP molecules. This ensures the synthesis of various products required in different growth conditions, demonstrating the adaptability and evolvability of bacterial gene regulation.

Additionally, the regulation of gene expression at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels plays a crucial role in avoiding the accumulation of pathway intermediates and wasteful consumption of resources. By regulating enzyme activity through feedback inhibition, allosteric regulation, and reversible chemical modifications, bacteria can optimize their energy management and adapt their metabolic responses to changing environmental conditions.

Gene regulation is essential for the survival and versatility of bacteria. It allows them to efficiently utilize resources, respond to stresses, and adapt to fluctuating environments. The complex interplay of regulatory mechanisms and signals enables bacteria to fine-tune their gene expression, ensuring their adaptability and survival in diverse conditions.

The White House Press Secretary: Their Role and Responsibilities

You may want to see also

Transcription factors and global physiology of the cell control gene expression

In the context of gene expression in bacteria, transcription factors and the global physiology of the cell play a shared and interconnected role in control and regulation. Bacterial cells continuously adjust their gene expression in response to environmental changes. This adjustment involves transcription factors that sense metabolic signals and activate or inhibit target genes.

Transcription factors, alongside DNA-binding transcription factors and other specific regulators, influence gene expression. However, they are not the primary coordinators of gene expression changes during growth transitions. Instead, they complement the effect of global physiological control mechanisms. The global physiological state of the cell, particularly the activity of the gene expression machinery, plays a more significant role in controlling the transcriptional response of the network.

The regulatory network includes interactions that dominate the transcriptional response, such as the activation of all genes by the physiological state of the cell. For example, the activation of the acs gene by Crp·cAMP, a combination of the transcription factor Crp and the signaling metabolite cAMP, is influenced by the global physiological state. The absence or presence of a strong regulatory effect from transcription factors is dependent on the specific promoter being considered.

The global physiological state affects the expression of all genes in the network. This is demonstrated by the central regulatory circuit involved in controlling carbon metabolism in E. coli, which consists of the two pleiotropic transcription factors Crp and Fis. Crp·cAMP stimulates the expression of the acs gene, while Fis counteracts this effect by inhibiting the transcription of crp and its own gene, fis. This cross-regulation and auto-regulation of gene expression highlight the complex interplay between transcription factors and the global physiology of the cell in controlling gene expression.

Understanding the Constitution: A Quick Read or a Lifetime Study?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The variation of gene expression is influenced by growth phases

The variation in gene expression during different growth phases has been studied using transcriptomics and metagenomics. These approaches have helped to observe gene expression patterns and bacterial growth dynamics in natural conditions within a microbial community.

Bacterial gene expression depends on specific regulations and directly on bacterial growth. The abundance of RNA polymerases and ribosomes, for instance, are growth-rate dependent. The growth rate of bacteria is a key characteristic of the state of the cell, and thus, gene expression is often growth-rate dependent.

During the lag phase, ABC transporters, which may be linked to active substrate utilization, are increasingly expressed as the cells prepare for division. In the exponential phase, the functions of activated genes include the synthesis of amino acids (alanine and arginine), energy metabolism, and translation, all of which promote active cell division. The transition between the exponential and stationary phases is marked by physiological, morphological, and transcriptional differences. The stationary phase can be considered stressful, and genes involved in the control of the cell division rate decrease in expression, while genes involved in defense-related metabolic pathways increase in expression to ensure cell survival in nutrient-deprived conditions.

The growth rate of a bacterial population depends on how well the growth conditions match the bacteria's requirements. Factors such as oxygen, pH, temperature, and light impact microbial growth. The study of gene expression patterns during different growth phases helps understand the response of bacteria to external factors, such as changes in microbial population density and nutrient availability.

The Preamble: Constitution's Mission Statement

You may want to see also

Environmental factors determine the optimal constitutive expression levels

The expression of constitutive genes in bacteria is a fascinating area of study, offering insight into how microbes adapt to changing environments. Constitutive genes maintain a constant level of expression, and are also called "housekeeping genes", for example, ribosomal RNA genes involved in protein synthesis.

Environmental factors play a critical role in determining the optimal constitutive expression levels. The focus is on maximising net growth in a dynamic environment. A widely observed strategy is the passive "intermediate" strategy, where cells express an intermediate phenotype in all environments. This is advantageous as it allows for a quick response to environmental fluctuations. This strategy is utilised by many procaryotic and eucaryotic genes, despite the demand for expression varying over time.

The optimal constitutive expression level is dependent on the costs and benefits associated with the expression level. In certain cases, growth is maximised by expressing the gene at an intermediate level, while in other cases, the gene is either fully expressed or fully repressed. Interestingly, the optimal constitutive expression level in a changing environment is distinct from the time-averaged demand for the gene product.

The choice between constitutive and responsive expression strategies is influenced by environmental and inter-cellular noise, which favours a responsive strategy. The interplay between the demand frequency for a gene product, the genetic response rate, and fitness is a key consideration.

Bacteria utilise different σ subunits of bacterial RNA polymerase to facilitate rapid and global shifts in gene expression in response to environmental cues. The σ factor recognises specific sequences within bacterial promoters, allowing bacteria to express the genes that are useful in new environmental conditions. For example, in sporulating bacteria, a group of σ factors regulates the expression of genes required for sporulation when stimulated by specific signals.

Interstate Commerce: Who Holds the Constitutional Power?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Constitutive genes are genes that have the same level of expression. They are also called housekeeping genes. An example is ribosomal RNA, which is involved in protein synthesis.

The tryptophan (trp) operon is an example of constitutive gene regulation in bacteria. When there is an abundance of tryptophan in the environment, bacteria turn off the trp operon and use the environmental tryptophan to build proteins. When tryptophan levels are low, bacteria turn on the trp operon to synthesize tryptophan.

Responsive gene expression adapts to the changing environment, while constitutive expression remains constant. Responsive strategies are favored in dynamic environments with varying nutrient levels, temperatures, and toxin concentrations.

Gene regulation in bacteria involves transcription factors and the global physiology of the cell. Transcription factors can be repressors, which suppress gene expression, or activators, which enhance gene expression. The physiological state of the cell and these transcription factors control gene expression across growth phases.

The bacterial toxin cyclohexamide is a regulatory protein that inhibits eukaryotic translation.