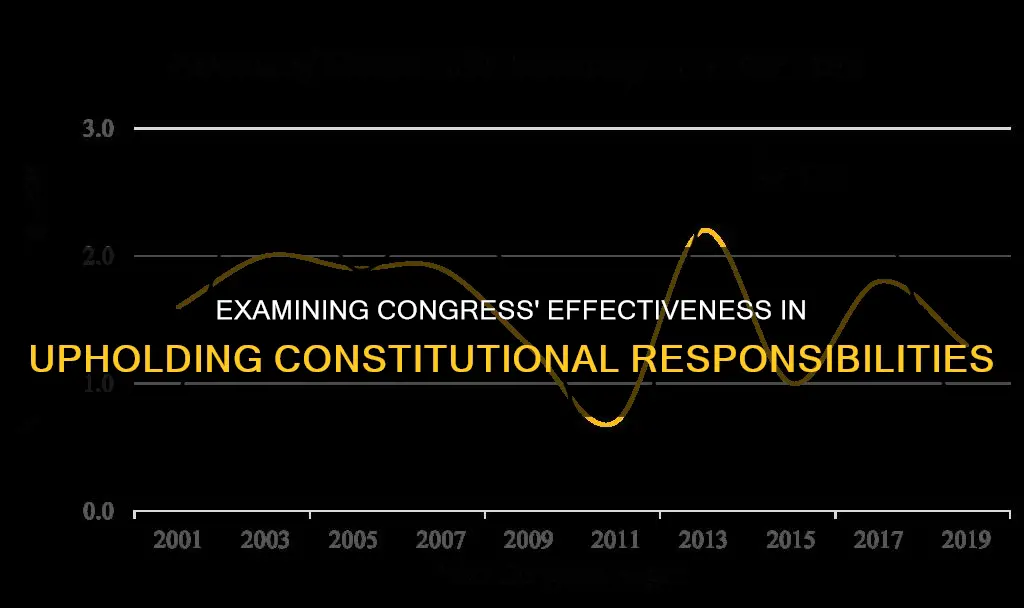

The United States Congress is the legislative branch of the federal government, established by Article I of the Constitution. It is comprised of the House of Representatives and the Senate, with each house fulfilling specific constitutional duties. These duties include the enactment of legislation, the declaration of war, the confirmation or rejection of presidential appointments, and investigative powers. Congress also has the power to levy taxes and tariffs to fund the government and mandate spending on specific items. In recent years, there has been criticism of Congress's effectiveness in fulfilling its constitutional duties, particularly regarding its role as a legislator and its power to declare war. However, some argue that Congress is effective when working in bipartisan cooperation with other branches of government, such as in foreign policy decisions. The extent to which Congress successfully executes its constitutional responsibilities is a matter of ongoing debate.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Effectiveness in fulfilling constitutional duties | Not effective as Congress has failed to use its power to declare war and has not effectively used its power as a legislator |

| Effectiveness in maintaining power in foreign policy | Not effective as Congress has allowed the president to exploit his role as Commander-in-Chief and formulate his own legislature |

| Effectiveness in maintaining power over the executive | Effective as Congress still has power over the executive |

| Effectiveness in maintaining investigative powers | Effective as Congress has substantial investigative powers |

| Effectiveness in maintaining power to legislate | Not effective as Congress has failed to use its power to legislate |

| Effectiveness in maintaining power to organize the judicial branches | Not effective as Congress has failed to use its power to organize the judicial branches |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Declaring war

The US Constitution grants Congress the power to "declare war". This authority has been used sparingly, with only five formal war declarations issued against ten foreign nations. The last time Congress declared war was on December 11, 1941, against Germany and Italy during World War II. Since then, US military actions have occurred without formal declarations of war, raising questions about the balance of war powers between Congress and the President.

The framers of the Constitution intended to prevent unilateral executive action by granting Congress the sole authority to declare war. This power was designed to ensure careful debate and restraint in the decision-making process. The Declare War Clause in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution states that Congress shall have the power to "declare war", indicating that legislative approval is necessary for initiating hostilities.

However, the extent to which this clause limits the President's ability to use military force without Congress's approval remains contested. While most scholars agree that the President cannot declare war independently, there is debate over whether they can initiate the use of force without a formal declaration. In modern times, Presidents have often used military force without formal declarations or express consent from Congress, such as in the case of President Truman and the Vietnam War.

Congress has attempted to rein in presidential war powers through legislation like the War Powers Resolution, passed in 1973 over President Nixon's veto. This resolution aimed to ensure that both Congress and the President collectively decide on the introduction of US armed forces into hostilities. Nonetheless, the resolution has had little effect on presidential military decisions.

The declaration of war triggers a series of domestic statutes that grant the President and the executive branch substantial powers. These include the ability to take over businesses and transportation systems, detain foreign nationals, conduct warrantless spying, and utilise natural resources on public lands. As such, the constitutional division of war powers between Congress and the President remains a critical aspect of US governance, with ongoing debates about the appropriate balance of authority.

Continental Congress: Forging the US Constitution

You may want to see also

Legislative powers

The US Constitution grants Congress the authority to enact legislation and declare war, confirm or reject presidential appointments, and investigate. Congress has the sole power to make laws, and all legislative power in the government is vested in Congress.

Congress has the power to levy taxes and tariffs to fund the government and may authorize borrowing if there is a shortfall. It can also mandate spending on specific items. Both chambers of Congress have investigative powers and may compel the production of evidence or testimony.

Congress is also responsible for organizing the judicial branches and has the power to raise and support armies, although appropriations for this purpose are limited to two years. Congress can also call forth the militia to execute laws, suppress insurrections, and repel invasions.

Congress has not effectively used its power to declare war, with the last formal declaration of war being in 1942 against Romania. Presidents have declared wars without Congress in Korea, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Vietnam. This has resulted in Congress taking a back seat while the president deals with foreign affairs.

Congress has also failed to fulfil its role as a legislator, with the president using executive orders to fix Congress's failures. For example, in 2014, the president had to sign an executive order to help 5 million immigrants due to Congress facing a gridlock when trying to pass policy.

The US Cabinet: Who's in the Exclusive Club?

You may want to see also

Confirming or rejecting presidential appointments

The US Constitution's Appointments Clause gives the president the power to nominate and appoint public officials, with the advice and consent of the Senate. This includes ambassadors, Cabinet secretaries, federal judges, and Supreme Court justices. The Senate's role is to scrutinize and confirm or reject these nominations, providing a check on the president's power.

The confirmation process can be challenging, with nominees facing rigorous Senate hearings. Nominees must complete background checks, financial disclosures, and committee questionnaires. The Senate committees can recommend approval, disapproval, or provide no recommendation. Most nominees are eventually confirmed, but some are withdrawn or rejected. The Senate's scrutiny of nominees has increased over time, and the rules have evolved to require a simple majority to end debate and bring a nomination to a vote.

The Appointments Clause distinguishes between two types of officers: principal officers, who must be appointed by the President with Senate confirmation, and inferior officers, whose appointment Congress may vest in the President, judiciary, or department heads. This separation of powers ensures that Congress cannot fill offices with its supporters, maintaining the President's control over the executive branch.

While the President has the power to nominate, the Senate's advice and consent role provides a check and balance, ensuring accountability in staffing important government positions. The confirmation process allows the Senate to assess the nominee's qualifications, character, and suitability for the role.

In summary, the Senate plays a crucial role in confirming or rejecting presidential appointments, ensuring a balanced and qualified executive branch, while also respecting the President's authority to nominate individuals to serve in these positions.

Funding for Schools: Is It in the 1876 Constitution?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Investigative powers

The investigative powers of the US Congress are extensive and far-reaching. While the Constitution does not expressly grant Congress the power to conduct investigations, it has been interpreted as having an inherent, constitutional prerogative to do so. This power has been recognised by Congress and the courts since the first congressional investigation in 1792.

Congressional investigations primarily serve to gather information valuable for considering and producing legislation, or to inform the public. They can also be used to oversee federal departments and executive agencies, and to decide whether legislation is appropriate. The investigative powers of Congress are so extensive that they have been described as "almost boundless in practice".

However, the investigative powers of Congress are not unlimited. They are tied to its authority to legislate, and so the limits of congressional investigations are linked to the limits of Congress's constitutional authority. Congress has no general authority to investigate the private affairs of ordinary citizens. The doctrine of separation of powers also places constraints on its investigative powers. For example, Congress cannot investigate matters committed to the President's discretion, such as an individual's entitlement to a pardon.

Congressional investigations can be conducted by committees or subcommittees, which can compel people to appear and give testimony using subpoena power if necessary. Refusal to cooperate with a Congressional subpoena can result in charges of contempt of Congress, which could result in a prison term.

The Supreme Court rarely engages in discussions of Congress's investigatory power and has only once issued an opinion directly addressing an investigative oversight conflict between Congress and the Executive Branch.

Compromises: The Foundation of the US Constitution

You may want to see also

Declaring bills as law

The United States Congress is made up of the House of Representatives and the Senate, and it is the only part of the US government that can make new laws or change existing ones.

A bill must pass both houses of Congress before it goes to the President for consideration. The President then has several options. If the President agrees with the bill, they may sign it into law. If the President believes the law to be bad policy, they may veto it and send it back to Congress. Congress may override the veto with a two-thirds vote of each chamber, at which point the bill becomes law. If Congress is in session and the President takes no action within 10 days, the bill becomes law. If Congress adjourns before 10 days are up and the President takes no action, then the bill dies and Congress may not vote to override.

Congress has the power to legislate, but in recent years there has been a decline in the use of this power, with Congress failing to fulfil its role as a legislator. For example, in 2014, the President had to sign an executive order to help 5 million immigrants, taking over from Congress, which was facing a gridlock when trying to pass policy.

Congress has not used its power to declare war since 1942 when it declared war on Romania. In contrast, the President has declared wars in Korea, Afghanistan, Iraq and Vietnam without formal declarations.

The Supreme Court's Power: Understanding the Supremacy Clause

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The US Constitution grants Congress the authority to enact legislation, declare war, confirm or reject presidential appointments, and exercise investigative powers. Congress also has the power to levy taxes and tariffs, borrow money, and mandate spending.

Congress has faced criticism for not effectively exercising its legislative powers. In recent years, there has been a decline in Congress's use of its legislative powers, with the President resorting to executive orders to address issues where Congress faced gridlock.

A lack of bipartisanship with other branches of the government has hindered Congress's effectiveness. For example, President Obama's threat of vetoes in 2015 limited Congress's ability to challenge his policies. However, Congress has shown bipartisanship in foreign policy, granting the President authorisation to use military force.

The President has had to use executive orders to address issues where Congress faced gridlock. Additionally, the President's power as Commander-in-Chief has been exploited, with Congress not using its power to declare war since 1942.