Political machines are organized networks of party leaders, activists, and voters that operate within a specific geographic area, often a city or region, to gain and maintain political power. These systems function by exchanging resources, such as jobs, contracts, or services, for political support, typically in the form of votes or loyalty. At their core, political machines rely on a hierarchical structure where a central boss or leader controls patronage, distributes favors, and ensures the machine’s survival through a combination of grassroots mobilization and strategic alliances. They thrive in environments with weak institutional oversight, high levels of inequality, or fragmented political systems, leveraging personal relationships and informal networks to dominate local politics. While often criticized for corruption or clientelism, political machines can also deliver tangible benefits to their constituents, making them complex and enduring features of many political landscapes.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Patronage Networks: How political machines distribute jobs, contracts, and favors to secure loyalty and support

- Voter Mobilization: Tactics like get-out-the-vote efforts, transportation, and direct outreach to ensure voter turnout

- Boss Leadership: The role of powerful leaders who control resources and make key decisions within the machine

- Community Control: Dominance over local institutions like courts, police, and businesses to maintain influence

- Corruption Mechanisms: Use of bribery, fraud, and illegal practices to manipulate elections and policies

Patronage Networks: How political machines distribute jobs, contracts, and favors to secure loyalty and support

Political machines thrive on a simple yet powerful currency: patronage. This system of reciprocal exchange forms the backbone of their influence, weaving a complex web of loyalty and support through the strategic distribution of jobs, contracts, and favors. At its core, patronage is a transactional relationship where political machines offer tangible benefits in exchange for unwavering allegiance, votes, and political capital. This quid pro quo dynamic ensures the machine’s survival and dominance in local or regional politics.

Consider the historical example of Tammany Hall in 19th-century New York City. This Democratic political machine mastered the art of patronage by appointing loyalists to government positions, awarding construction contracts to sympathetic businesses, and providing favors like legal assistance or housing to immigrants. In return, these beneficiaries became reliable voters and foot soldiers for the machine’s campaigns. The system was so effective because it addressed immediate needs—jobs for the unemployed, contracts for struggling businesses, and support for marginalized communities—while cementing the machine’s control over political institutions.

However, the mechanics of patronage networks are not without risks or ethical dilemmas. Critics argue that such systems often prioritize loyalty over competence, leading to inefficiency and corruption. For instance, awarding contracts based on political allegiance rather than merit can result in subpar public works or inflated costs. Similarly, filling government positions with unqualified loyalists undermines the effectiveness of public services. To mitigate these risks, political machines must balance their patronage strategies with a degree of transparency and accountability, ensuring that the benefits of their actions extend beyond their inner circle to the broader community.

Building an effective patronage network requires careful planning and execution. First, identify key constituencies whose support is critical to your political goals. Next, assess their needs—whether it’s employment opportunities, business contracts, or personal favors—and align your resources to meet those needs. For example, if you’re targeting small business owners, prioritize awarding municipal contracts to those who demonstrate loyalty. For unemployed voters, create job programs within government agencies or affiliated organizations. Finally, maintain a ledger of favors given and received to ensure reciprocity and prevent free-riding.

In conclusion, patronage networks are both a tool and a test of a political machine’s ability to sustain power. When executed strategically, they can foster deep-rooted loyalty and mobilize support across diverse demographics. However, their success hinges on balancing self-interest with the public good, ensuring that the benefits of patronage extend beyond the machine’s inner circle. By understanding the mechanics of these networks and their historical context, modern political operatives can navigate the ethical complexities of patronage while maximizing its potential to secure long-term influence.

Is Deception Essential in Political Strategy and Governance?

You may want to see also

Voter Mobilization: Tactics like get-out-the-vote efforts, transportation, and direct outreach to ensure voter turnout

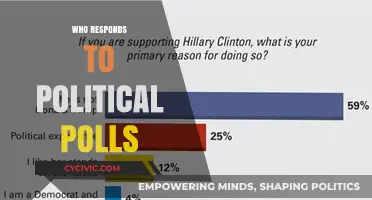

Political machines thrive on voter turnout, and their success hinges on meticulous mobilization tactics. One cornerstone is the "get-out-the-vote" (GOTV) effort, a blitz of reminders and encouragement in the final days before an election. This isn't a scattershot approach; it's targeted. Machines leverage voter data to identify their base, often using door-to-door canvassing, phone banking, and personalized mailers. For instance, the Daley machine in Chicago famously deployed precinct captains to knock on doors, not just to remind voters of Election Day, but to offer a ride to the polls or even a cup of coffee afterward. This personal touch, combined with a sense of obligation, proved remarkably effective.

Research shows that direct contact increases turnout by 5-10%, a significant margin in close races.

Transportation is another critical tool. Machines understand that logistical barriers can deter even the most loyal supporters. They organize carpools, rent buses, and even provide taxi vouchers to ensure voters, particularly the elderly, disabled, or those without reliable transportation, can cast their ballots. This tactic is especially potent in urban areas where polling places can be distant or difficult to access. Imagine a single mother working two jobs; a machine offering childcare and a ride to the polls removes a major obstacle to her participation.

This logistical support isn't just altruistic; it's a strategic investment in securing votes.

Direct outreach goes beyond mere reminders. It involves building relationships and fostering a sense of community. Machines cultivate networks through local organizations, churches, and social clubs, creating a web of influence that extends far beyond election season. Precinct captains become familiar faces, addressing concerns, providing assistance, and earning trust. This long-term engagement ensures that when election time arrives, voters feel a personal connection to the machine and its candidates. Think of it as political relationship building, where the currency is not just votes, but loyalty and a sense of belonging.

However, these tactics aren't without ethical considerations. Critics argue that such intensive mobilization can border on coercion, particularly when coupled with promises of favors or threats of retribution. The line between encouragement and pressure can be thin. Machines must navigate this carefully, ensuring their efforts empower voters rather than manipulate them. Transparency and accountability are crucial to maintaining legitimacy in the democratic process.

The Origins of Political Buttons: A Historical Campaign Evolution

You may want to see also

Boss Leadership: The role of powerful leaders who control resources and make key decisions within the machine

At the heart of every political machine lies a powerful leader, often referred to as the "boss," whose influence and control are pivotal to the machine's operation. These bosses are not merely figureheads but strategic masterminds who wield significant authority over resources, decision-making, and the distribution of power within their organizations. Their role is multifaceted, encompassing patronage, strategy, and the delicate balance of maintaining loyalty among followers.

Consider the historical example of Boss Tweed, the notorious leader of Tammany Hall in 19th-century New York. Tweed controlled access to jobs, contracts, and favors, ensuring that his political machine dominated local politics. His ability to allocate resources—whether through government positions or public works projects—cemented his authority and kept the machine well-oiled. This model of boss leadership illustrates how centralized control over resources becomes the lifeblood of the machine, enabling it to deliver tangible benefits to constituents while securing political dominance.

However, the effectiveness of boss leadership hinges on more than just resource control; it requires a keen understanding of human dynamics. Bosses must navigate complex networks of alliances, manage rivalries, and maintain a delicate balance between rewarding loyalty and punishing dissent. For instance, a boss might strategically distribute patronage jobs to key supporters while withholding them from potential adversaries. This calculated approach ensures that the machine remains cohesive and that the boss’s authority remains unchallenged.

To emulate this style of leadership, aspiring bosses should focus on three critical steps: first, establish clear control over key resources, whether financial, political, or social. Second, cultivate a loyal network by consistently rewarding supporters and addressing their needs. Third, maintain a proactive stance in decision-making, ensuring that every move aligns with the machine’s long-term goals. Caution, however, must be exercised to avoid becoming a target of public scrutiny or legal backlash, as excessive centralization of power can lead to corruption and downfall.

In conclusion, boss leadership is the linchpin of political machines, blending resource control, strategic decision-making, and relationship management. By mastering these elements, a leader can transform a disparate group of individuals into a cohesive, powerful machine capable of shaping political landscapes. The key takeaway is that while resources provide the means, it is the boss’s ability to wield them wisely that sustains the machine’s influence.

Navigating Political Careers: Strategies for Success in Public Service

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Community Control: Dominance over local institutions like courts, police, and businesses to maintain influence

Political machines thrive on a simple principle: control the levers of local power, and you control the community. This isn't achieved through overt coercion, but through a web of influence woven into the very fabric of daily life. Courts, police departments, and businesses become extensions of the machine, their decisions and actions subtly guided to benefit those in control.

A judge might look favorably upon a machine-backed defendant, a police chief might turn a blind eye to certain activities in machine-friendly neighborhoods, and local businesses might find lucrative contracts flowing their way in exchange for loyalty.

Consider the Tammany Hall machine in 19th-century New York. They didn't just win elections; they dominated the city's institutions. Tammany-appointed judges ensured favorable rulings, Tammany-controlled police turned a blind eye to their illicit activities, and Tammany-backed businesses flourished under their protection. This web of control wasn't just about power; it was about creating a system where the machine's survival became synonymous with the community's well-being.

Need a building permit? Tammany could expedite it. Facing legal trouble? Tammany could "smooth things over." This symbiotic relationship, though often corrupt, fostered a sense of dependence, making the machine indispensable.

This dominance isn't always overt. It's often a matter of subtle pressures, unspoken understandings, and a shared history of favors exchanged. A police officer might be more inclined to "look the other way" during a machine-organized event, not out of fear, but out of a sense of loyalty or a desire to avoid rocking the boat. A business owner might contribute to the machine's war chest, not solely out of coercion, but because they understand the unspoken benefits of being "in the loop."

Breaking this cycle of control requires transparency, accountability, and a vigilant citizenry. Independent oversight bodies, robust whistleblower protections, and a free press are essential tools in dismantling these networks of influence. Ultimately, the health of a democracy depends on institutions serving the public good, not the interests of a powerful few.

What Drives Political Revolutionaries: Unraveling the Eternal Flame of Change

You may want to see also

Corruption Mechanisms: Use of bribery, fraud, and illegal practices to manipulate elections and policies

Political machines often thrive on a foundation of corruption, employing bribery, fraud, and illegal practices to secure power and influence. These mechanisms are not mere anomalies but systematic strategies designed to manipulate elections and shape policies in favor of the machine’s operatives. Bribery, for instance, is a direct tool used to buy loyalty, silence opposition, or secure favorable votes. In Chicago’s infamous Democratic machine during the early 20th century, ward bosses distributed cash, jobs, and favors to ensure voter turnout and compliance. This quid pro quo system creates a dependency cycle, where constituents feel obligated to support the machine in exchange for immediate benefits, often at the expense of long-term community welfare.

Fraud operates more subtly but is equally destructive. Voter fraud, such as ballot stuffing or falsifying voter registrations, distorts election outcomes to favor the machine. A notable example is the 1948 U.S. Senate election in Texas, where Lyndon B. Johnson’s campaign allegedly added 200 fraudulent votes in Jim Wells County to secure a narrow victory. Modern machines may use digital manipulation, like hacking voter databases or spreading disinformation, to sway public opinion. These tactics undermine democratic integrity, eroding trust in electoral processes and institutions.

Illegal practices extend beyond elections to policy manipulation. Political machines often control local governments, using their power to award contracts to allies or block initiatives that threaten their dominance. In post-Soviet states, oligarchs have leveraged their wealth to influence legislation, ensuring policies protect their interests rather than the public’s. This systemic corruption creates a feedback loop: machines gain resources through illicit means, which they then use to strengthen their grip on power, making reform nearly impossible.

To combat these mechanisms, transparency and accountability are essential. Implementing stricter campaign finance laws, independent oversight bodies, and digital security measures can disrupt the cycle of corruption. Citizens must also remain vigilant, demanding ethical governance and holding leaders accountable. While political machines may exploit human vulnerabilities, informed and engaged communities can dismantle their illicit structures, restoring integrity to the political process.

Mastering Political Economy Analysis: Strategies for Understanding Complex Systems

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political machine is an organized group or system that uses its power and resources to gain and maintain political control, often through patronage, favors, and influence over voters and officials.

Political machines gain power by offering services, jobs, or favors to voters in exchange for their loyalty and votes, while maintaining control through a network of local leaders and operatives who ensure continued support.

Patronage is central to political machines, as they distribute government jobs, contracts, and resources to supporters, creating a system of dependency and loyalty that strengthens their political influence.

While not inherently illegal, political machines often operate in a gray area, and their activities are regulated by laws against corruption, bribery, and voter fraud. However, enforcement varies widely by region.

Notable examples include Tammany Hall in New York City during the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Daley machine in Chicago, and various modern-day systems in countries where local power brokers dominate politics.