Political polls serve as a critical tool for gauging public opinion on various issues, candidates, and policies, but the demographic composition of those who respond to these surveys often raises questions about their representativeness. Typically, respondents to political polls tend to be more politically engaged, older, and more educated than the general population, as these groups are more likely to have the time, interest, and access to participate. Younger individuals, minorities, and those with lower socioeconomic status are often underrepresented, which can skew results and create challenges in accurately reflecting the broader electorate. Additionally, factors such as survey methodology, question wording, and the mode of polling (e.g., phone, online, in-person) can influence who chooses to respond, further complicating efforts to ensure a balanced and inclusive sample. Understanding who responds to political polls is essential for interpreting their findings and addressing potential biases in public opinion research.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Demographic Groups: Age, gender, race, education, income, and geographic location influence poll response rates

- Political Affiliation: Partisanship affects willingness to participate in polls, with stronger partisans more likely to respond

- Survey Methodology: Phone, online, or in-person methods impact who responds due to accessibility and trust

- Motivation Factors: Interest in politics, civic duty, or incentives like rewards drive participation in polls

- Non-Response Bias: Certain groups (e.g., young, less educated) are less likely to respond, skewing results

Demographic Groups: Age, gender, race, education, income, and geographic location influence poll response rates

Political poll response rates aren’t uniform across demographic groups, and understanding these disparities is crucial for interpreting results accurately. Age, for instance, plays a significant role: younger adults (18–29) are less likely to respond to traditional phone surveys but more likely to engage with online polls. Conversely, older adults (65+) tend to answer landline calls, skewing results toward their perspectives. This age-based divide highlights the need for pollsters to diversify methods to capture a balanced sample. Without such adjustments, polls risk overrepresenting the views of older, more accessible demographics.

Gender and race also influence response patterns, though in more nuanced ways. Women, for example, are slightly more likely than men to participate in political polls, possibly due to higher civic engagement in certain contexts. However, racial minorities, particularly Black and Hispanic communities, are often underrepresented in surveys. Language barriers, distrust of institutions, and lower response rates to cold calls contribute to this gap. Pollsters must address these challenges by offering multilingual surveys, building trust through community partnerships, and using targeted outreach strategies to ensure inclusivity.

Education and income levels further complicate the demographic landscape. Highly educated individuals and those with higher incomes are more likely to respond to polls, creating a bias toward their political leanings. For instance, college graduates are twice as likely to participate as those with a high school diploma or less. Similarly, lower-income households often face barriers like limited access to technology or time constraints, reducing their representation. To mitigate this, pollsters should weight responses to reflect population demographics and consider incentives for underrepresented groups.

Geographic location is another critical factor, as response rates vary widely by region and urban-rural divides. Urban residents are more likely to participate in polls than rural residents, partly due to greater exposure to survey opportunities and higher population density. Additionally, certain states or regions may be overrepresented due to easier access or higher political engagement. For example, residents of swing states are often polled more frequently, skewing national averages. Pollsters must account for these geographic disparities by oversampling rural areas or less-polled regions to achieve a nationally representative sample.

In practice, addressing these demographic disparities requires a multi-faceted approach. Pollsters should employ mixed-mode surveys—combining phone, online, and mail methods—to reach diverse groups. They must also use rigorous weighting techniques to adjust for over- or underrepresentation. For instance, if 60% of respondents are college-educated but only 33% of the population is, weights can correct this imbalance. Finally, transparency about response rates and demographic breakdowns is essential for users to interpret poll results critically. By acknowledging and actively addressing these demographic influences, polls can better reflect the true political pulse of a population.

Unveiling the Hidden Mechanisms: How Politics Really Works Behind the Scenes

You may want to see also

Political Affiliation: Partisanship affects willingness to participate in polls, with stronger partisans more likely to respond

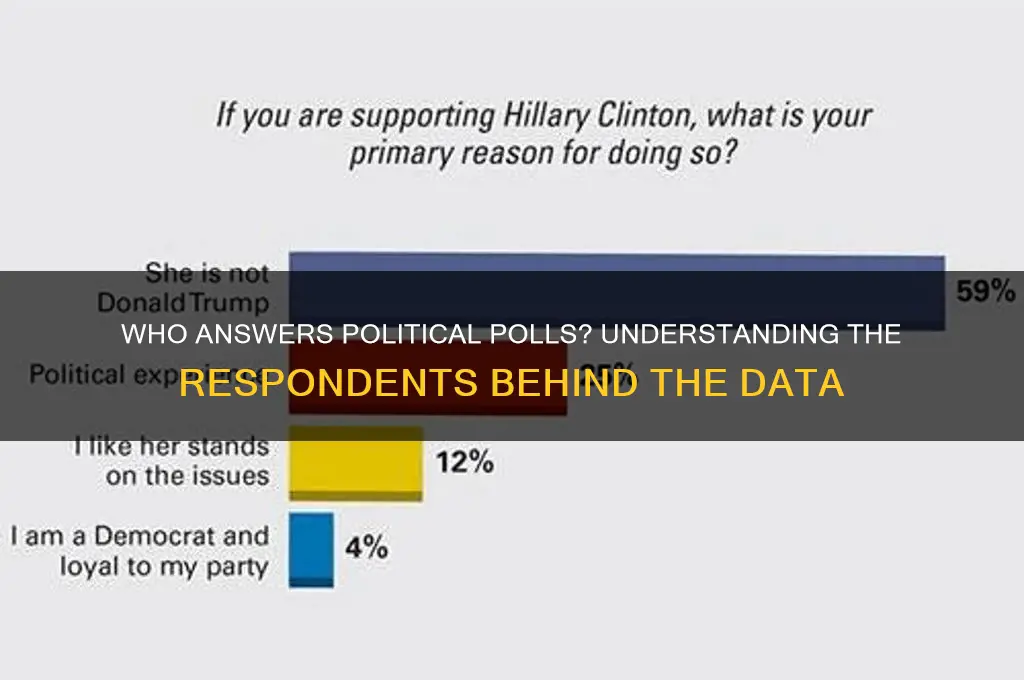

Stronger partisans—individuals with deeply entrenched political loyalties—are disproportionately represented in poll responses. This skew isn’t accidental. Research shows that those with intense party identification are 25-35% more likely to participate in political surveys compared to independents or weak partisans. Why? Partisans view polls as battlegrounds for their ideology, amplifying their voices to shape narratives. For instance, during the 2020 U.S. election cycle, self-identified "strong Republicans" and "strong Democrats" responded to polls at nearly double the rate of moderates, according to Pew Research Center data. This behavior reflects a psychological drive to validate their beliefs and influence public perception.

Consider the mechanics of this phenomenon. Partisanship acts as a filter, where stronger affiliation correlates with higher political engagement—attending rallies, donating, and yes, answering polls. A 2018 study in *Political Behavior* found that strong partisans are 40% more likely to perceive polls as "opportunities to advocate" rather than neutral data collection. This mindset transforms polling participation into an act of political activism. Conversely, weak partisans or independents often view polls as irrelevant or intrusive, reducing their response rates. Pollsters must account for this bias by weighting responses to balance overrepresentation, though even weighted data can retain residual partisan skew.

To mitigate this distortion, pollsters employ strategies like quota sampling or probabilistic modeling. For example, Gallup adjusts responses based on census data to align demographic and partisan distributions. However, no method is foolproof. Stronger partisans’ higher response rates can still inflate their group’s influence, particularly in volatile political climates. A practical tip for interpreting polls: Scrutinize the partisan breakdown of respondents. If strong partisans comprise over 40% of the sample, treat the findings with caution, as they may exaggerate ideological divides.

The takeaway is clear: Partisanship isn’t just a predictor of voting behavior—it’s a driver of poll participation. Stronger partisans respond more frequently, not merely out of habit, but with intent. This dynamic underscores the challenge of achieving representative samples in an era of polarized politics. For consumers of polling data, understanding this bias is critical. It transforms passive reading of percentages into active evaluation of methodology, ensuring a clearer grasp of public opinion’s true contours.

Catholicism and Politics: Exploring the Complex Relationship and Influence

You may want to see also

Survey Methodology: Phone, online, or in-person methods impact who responds due to accessibility and trust

The choice of survey methodology—phone, online, or in-person—significantly shapes who responds to political polls, driven by differences in accessibility and trust. Phone surveys, for instance, often reach older demographics more effectively, as this group tends to be more accustomed to and trusting of landline communication. However, younger respondents, who rely heavily on mobile devices, may be less likely to answer unknown calls due to skepticism about telemarketing or scams. This age-based disparity highlights how method accessibility directly influences response rates and, consequently, the representativeness of the sample.

Online surveys, on the other hand, excel in reaching tech-savvy populations, particularly younger adults and those with consistent internet access. Platforms like email, social media, and dedicated survey websites are convenient for this group, but they exclude individuals without reliable internet or digital literacy. For example, a Pew Research study found that online panels often overrepresent higher-income and more educated respondents. This bias underscores the importance of considering both accessibility and demographic skew when designing online surveys. Additionally, the anonymity of online responses can increase trust among some participants, encouraging more candid answers, but it may also invite fraudulent responses if verification measures are lacking.

In-person surveys offer a unique advantage in building trust through face-to-face interaction, making them particularly effective in communities where personal connections are valued. For instance, door-to-door surveys in rural or tight-knit urban areas can yield higher response rates because respondents perceive the effort as more genuine. However, this method is time-consuming and costly, limiting its scalability. It also raises concerns about interviewer bias, as the presence of a surveyor can influence responses, especially on sensitive political topics. Practical tips for in-person surveys include training interviewers to maintain neutrality and ensuring diverse teams to minimize discomfort among respondents from different backgrounds.

Comparing these methods reveals trade-offs between accessibility and trust. Phone surveys are accessible to older populations but face declining response rates due to caller fatigue. Online surveys are efficient and cost-effective but risk excluding marginalized groups. In-person surveys foster trust but are resource-intensive. To mitigate these challenges, researchers often employ mixed-mode approaches, combining methods to broaden reach. For example, a study might use phone calls for older adults, online platforms for younger respondents, and in-person interviews for hard-to-reach communities. This hybrid strategy, while complex, can improve sample diversity and reduce bias.

Ultimately, the impact of survey methodology on response rates cannot be overstated. Researchers must carefully weigh the accessibility and trust factors associated with each method to ensure their findings accurately reflect the population of interest. Practical considerations, such as budget, timeline, and target demographics, should guide the choice of approach. By understanding these dynamics, pollsters can design more inclusive and reliable political surveys, contributing to a more accurate understanding of public opinion.

Political Leaders in Schools: Impact, Frequency, and Educational Significance

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

Motivation Factors: Interest in politics, civic duty, or incentives like rewards drive participation in polls

Political engagement isn't a one-size-fits-all phenomenon. Understanding who responds to political polls requires dissecting the motivations driving participation. While some individuals are intrinsically drawn to the political arena, others require external nudges. This interplay of internal and external factors shapes the demographic and ideological landscape of poll respondents.

Interest in politics acts as a powerful magnet, attracting individuals who actively seek out political information and discourse. These politically engaged citizens are more likely to respond to polls, driven by a desire to have their voices heard and contribute to the political conversation. They follow news outlets, engage in political discussions, and actively seek out opportunities to express their opinions.

This intrinsic motivation often correlates with higher levels of education and political knowledge, creating a potential bias in poll results towards more informed and engaged segments of the population.

Civic duty, a sense of obligation to participate in the democratic process, serves as another significant motivator. For some, responding to polls is an extension of their responsibility as citizens, a way to contribute to the collective decision-making process. This motivation can be particularly strong among older generations who were raised with a stronger emphasis on civic engagement and traditional notions of citizenship. However, fostering a sense of civic duty in younger generations, who may feel disconnected from traditional political institutions, presents a challenge for pollsters seeking representative samples.

Incentives, such as rewards or compensation, can significantly boost response rates, especially among less politically engaged individuals. Offering small monetary rewards, gift cards, or entries into prize draws can entice participation from those who might otherwise be uninterested or apathetic. While effective in increasing response rates, this approach raises concerns about the potential for bias. Individuals motivated solely by rewards may not accurately represent the broader population, skewing results towards those more responsive to material incentives.

Balancing these motivation factors is crucial for ensuring the accuracy and representativeness of political polls. Pollsters must employ a multi-pronged approach, combining targeted outreach to politically engaged individuals with strategies to engage those driven by civic duty and carefully designed incentive structures to attract less engaged citizens. By understanding and addressing these diverse motivations, pollsters can strive to create a more comprehensive and accurate snapshot of public opinion.

Is 'Of Course' Polite? Decoding Etiquette in Everyday Conversations

You may want to see also

Non-Response Bias: Certain groups (e.g., young, less educated) are less likely to respond, skewing results

Political polls often paint a picture of public opinion, but that picture can be distorted by non-response bias. This occurs when certain demographic groups—such as younger adults or those with lower educational attainment—are less likely to participate in surveys. For instance, a Pew Research Center study found that only 6% of respondents to a landline phone poll were under 30, despite this age group making up 22% of the U.S. population. This disparity highlights how non-response can skew results, making polls less representative of the population they aim to reflect.

Consider the mechanics of polling methods and their impact on response rates. Landline surveys, once a staple, now disproportionately reach older adults, as younger generations rely heavily on mobile phones. Similarly, online polls may exclude those with limited internet access, often individuals with lower incomes or education levels. Even when polls use multiple methods, response rates among younger or less educated groups remain low. This isn’t just a technical issue—it’s a systemic one, rooted in how polling methods align with the habits and accessibility of different demographics.

To mitigate non-response bias, pollsters must adopt strategies tailored to underrepresented groups. For young adults, text-based surveys or social media outreach can increase engagement. Incentives, such as small rewards or entry into prize drawings, have shown promise in boosting response rates across all demographics. Additionally, weighting responses—statistically adjusting results to reflect the actual population distribution—can help correct for imbalances. However, these methods are not foolproof; they rely on accurate demographic data and assumptions about non-respondents’ views, which may still introduce errors.

The consequences of non-response bias are far-reaching, particularly in political polling. If younger or less educated voters are underrepresented, polls may overestimate support for candidates or policies favored by older, more educated respondents. This can mislead campaigns, media, and voters, potentially influencing election outcomes. For example, in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, polls underpredicted support for Donald Trump, partly due to lower response rates among his key demographics. Such inaccuracies erode trust in polling and highlight the urgent need for more inclusive methods.

Ultimately, addressing non-response bias requires a shift in how polls are designed and conducted. Pollsters must prioritize accessibility, using diverse methods to reach underrepresented groups. Equally important is transparency: clearly reporting response rates and demographic breakdowns allows audiences to assess poll reliability. While eliminating bias entirely may be impossible, acknowledging its presence and taking proactive steps to minimize it can lead to more accurate, equitable representations of public opinion.

Unveiling AARP's Political Stance: Bias or Neutral Advocacy?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political poll respondents are often a mix of registered voters, likely voters, and sometimes the general public, depending on the poll's focus and methodology.

Pollsters aim for representativeness by using sampling techniques, but response rates and biases (e.g., non-response or partisan leanings) can affect how well the sample reflects the broader population.

No, respondents come from various political affiliations, though some polls may target specific groups. Pollsters often weight responses to ensure balance across demographics and political leanings.