Contemporary political parties differ significantly from those of 1860 in terms of structure, ideology, and methods of engagement. In the mid-19th century, parties like the Republicans and Democrats were largely decentralized, with local and state organizations holding considerable power, and their platforms were often dominated by issues such as slavery, states' rights, and economic policies tied to regional interests. Today, political parties are highly centralized, with national committees and leaders playing a dominant role, and their agendas have expanded to include a wide array of issues, such as healthcare, climate change, and social justice, reflecting the complexities of a globalized and diverse society. Additionally, modern parties rely heavily on digital media, data analytics, and sophisticated fundraising strategies to mobilize voters, whereas 1860s parties depended on newspapers, public rallies, and personal networks to spread their message and garner support. These shifts highlight the evolution of political parties from localized, issue-specific entities to national, multi-issue organizations adapted to the demands of the 21st century.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Ideological Clarity | 1860: Parties had distinct ideologies (e.g., Republicans anti-slavery, Democrats pro-states' rights). Contemporary: Parties have broader, often overlapping ideologies, with internal factions (e.g., progressive vs. moderate wings). |

| Party Structure | 1860: Loose, decentralized organizations with local bosses holding power. Contemporary: Highly centralized, with national committees, professional staff, and data-driven strategies. |

| Voter Base | 1860: Limited to white, property-owning men. Contemporary: Universal suffrage, diverse demographics, and targeted outreach to specific voter groups. |

| Campaign Methods | 1860: Rallies, newspapers, and pamphlets. Contemporary: Digital media, social networks, and sophisticated data analytics for micro-targeting. |

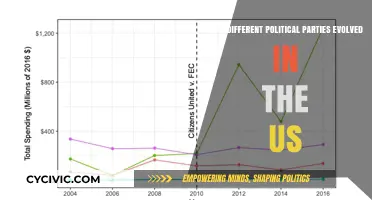

| Funding Sources | 1860: Wealthy donors and party bosses. Contemporary: Diverse funding, including PACs, super PACs, small donors, and crowdfunding. |

| Role of Media | 1860: Newspapers as primary information source, often partisan. Contemporary: 24/7 news cycle, social media, and fact-checking organizations influencing narratives. |

| Polarization | 1860: Regional divides (North vs. South). Contemporary: Extreme ideological polarization, with minimal cross-party cooperation. |

| Global Influence | 1860: Limited international focus. Contemporary: Parties engage in global issues, alliances, and foreign policy debates. |

| Technology Use | 1860: Nonexistent. Contemporary: Advanced tech for fundraising, voter mobilization, and messaging (e.g., AI, apps). |

| Issue Priorities | 1860: Slavery, tariffs, and states' rights. Contemporary: Climate change, healthcare, immigration, and economic inequality. |

| Party Loyalty | 1860: Strong regional and cultural loyalty. Contemporary: Declining party loyalty, rise of independent voters, and issue-based voting. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Ideological Shifts: Modern parties focus on diverse issues, unlike 1860's dominant slavery and states' rights debates

- Voter Demographics: Today's parties target broader, inclusive groups, contrasting 1860's limited, property-owning male voters

- Media Influence: Contemporary parties rely on digital campaigns, versus 1860's newspapers and public speeches

- Party Structures: Modern parties are centralized, professionalized, unlike 1860's loose, localized organizations

- Policy Complexity: Today's platforms address global issues, compared to 1860's narrow, domestically focused agendas

Ideological Shifts: Modern parties focus on diverse issues, unlike 1860's dominant slavery and states' rights debates

In the 1860s, American political discourse was dominated by two incendiary issues: slavery and states' rights. These debates tore the nation apart, culminating in the Civil War. Today, while echoes of these divisions persist, the ideological landscape has fragmented into a mosaic of diverse concerns. Modern political parties grapple with a spectrum of issues, from climate change and healthcare to immigration and economic inequality. This shift reflects not only societal evolution but also the complexities of a globalized, technologically advanced world.

Consider the Democratic and Republican platforms of today. While both parties still address traditional economic and social issues, their agendas are far more expansive. Democrats, for instance, prioritize climate action, advocating for renewable energy investments and carbon reduction targets. Republicans, on the other hand, often emphasize border security and deregulation. These priorities, though contentious, demonstrate how modern parties engage with a broader array of challenges than their 19th-century counterparts. The specificity of these issues—such as the Green New Deal or the construction of a border wall—underscores the granular nature of contemporary political debates.

This diversification of issues is not merely a matter of policy but also a reflection of demographic and technological change. The rise of social media has amplified marginalized voices, bringing issues like LGBTQ+ rights, racial justice, and mental health to the forefront. In 1860, such concerns were either nonexistent or relegated to the periphery of public discourse. Today, they are central to party platforms, with candidates tailoring their messages to appeal to diverse constituencies. For example, the 2020 Democratic primaries featured candidates explicitly addressing systemic racism, a stark contrast to the 1860s, when even the abolitionist movement was a fringe cause in mainstream politics.

However, this ideological broadening is not without challenges. The sheer volume of issues can dilute focus, making it difficult for parties to craft cohesive narratives. In 1860, the singularity of purpose—whether preserving the Union or defending slavery—lent clarity to political movements. Today, parties risk alienating voters by overloading their agendas. For instance, a candidate who champions both universal healthcare and student debt forgiveness may struggle to prioritize these issues in a way that resonates with all voters. This complexity demands strategic communication, a skill that was less critical in the more monolithic debates of the past.

Ultimately, the ideological shifts in political parties from the 1860s to today reflect both progress and new challenges. While the expansion of issues signifies a more inclusive and responsive political system, it also introduces complexities that test the coherence and effectiveness of party platforms. For voters, this means navigating a richer but more fragmented landscape. For parties, it requires balancing diverse priorities without losing sight of core principles. In this sense, the evolution of political ideologies is not just a historical curiosity but a practical guide to understanding—and perhaps improving—the mechanics of modern democracy.

Mark Wahlberg's Political Affiliation: Uncovering His Party Loyalty

You may want to see also

Voter Demographics: Today's parties target broader, inclusive groups, contrasting 1860's limited, property-owning male voters

In the 1860s, the electorate was a narrow slice of society: property-owning, predominantly white males. This demographic restriction meant political parties tailored their messages to a homogenous group, focusing on issues like land ownership, tariffs, and states' rights. Today, the landscape is unrecognizably different. Parties now court a vastly expanded electorate that includes women, racial minorities, young adults, and those without property. This shift demands a reorientation of campaign strategies, messaging, and policy priorities to resonate with diverse experiences and needs.

For instance, while the 1860s Republican Party might have focused on land grants for white settlers, today's GOP must address concerns ranging from suburban tax policies to rural broadband access, appealing to a much broader coalition.

This inclusivity isn't just about numbers; it's about representation. Consider the impact of the 19th Amendment, granting women the vote in 1920. This single act doubled the potential electorate, forcing parties to address issues like education, healthcare, and workplace equality. Similarly, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 dismantled barriers for Black voters, leading to a surge in attention to civil rights, economic justice, and racial equality within party platforms. Today, parties actively seek the support of young voters, a demographic increasingly concerned with climate change, student debt, and social justice. This necessitates a shift from the 1860s focus on agrarian interests to a more urban, technologically savvy, and globally conscious agenda.

A concrete example is the Democratic Party's emphasis on student loan forgiveness and climate change initiatives, directly targeting the concerns of younger, more diverse voters.

However, this broadened demographic reach presents challenges. Parties must navigate the complexities of intersecting identities and competing interests. A message that resonates with suburban women might not land with rural men, and policies benefiting one racial group might be perceived as detrimental by another. This requires a delicate balancing act, often resulting in nuanced messaging and targeted outreach strategies. For instance, a party might emphasize economic opportunity in one district while highlighting social justice issues in another, tailoring its approach to the specific demographics of each area.

Ultimately, the shift from a limited, property-owning male electorate to a diverse and inclusive voter base has fundamentally transformed the nature of political parties. It has forced them to become more adaptable, responsive, and representative, reflecting the complexities and aspirations of a modern, multifaceted society. This evolution, while challenging, is essential for ensuring that democracy truly serves all its citizens.

Why Avoid Politics and Religion? Navigating Sensitive Topics with Grace

You may want to see also

Media Influence: Contemporary parties rely on digital campaigns, versus 1860's newspapers and public speeches

The shift from 1860s newspapers and public speeches to contemporary digital campaigns marks a seismic change in how political parties engage with voters. In the 1860s, political messaging was confined to the printed word and live oratory, both of which required significant time and resources. Newspapers, often partisan in nature, served as the primary conduit for political ideas, while speeches at rallies or town halls allowed candidates to connect directly with audiences. Today, digital platforms enable parties to reach millions instantaneously, bypassing traditional gatekeepers and tailoring messages to hyper-specific demographics. This evolution reflects not just technological advancement but a fundamental redefinition of political communication.

Consider the mechanics of these mediums. In 1860, crafting a newspaper article or preparing a speech demanded meticulous planning and a deep understanding of rhetoric. Abraham Lincoln’s Cooper Union address, for instance, was a masterclass in persuasion, strategically delivered to sway Northern voters. Contrast this with modern digital campaigns, where data analytics, A/B testing, and micro-targeting dominate. A single tweet or Instagram ad can be optimized for engagement, shared virally, and adapted in real-time based on user feedback. While the 1860s relied on the eloquence of a single voice, contemporary campaigns thrive on the precision of algorithms and the speed of the internet.

However, this shift is not without its pitfalls. The immediacy of digital media often prioritizes brevity over depth, reducing complex policy issues to soundbites or memes. In the 1860s, voters might spend hours reading detailed editorials or attending lengthy speeches, fostering a deeper understanding of candidates’ platforms. Today, the average attention span online is a mere 8 seconds, forcing parties to distill their messages into bite-sized, emotionally charged content. This raises questions about the quality of political discourse and the potential for misinformation to spread unchecked in the digital age.

Practical tips for navigating this landscape are essential. For voters, cultivating media literacy is key—questioning sources, verifying facts, and seeking diverse perspectives. For political parties, balancing the efficiency of digital campaigns with the substance of traditional communication is crucial. Incorporating long-form content, such as podcasts or policy papers, alongside social media posts can help bridge this gap. Ultimately, while digital campaigns offer unprecedented reach, they must be wielded responsibly to preserve the integrity of democratic dialogue.

In conclusion, the transition from 1860s newspapers and speeches to contemporary digital campaigns underscores the transformative power of technology on political engagement. While the methods have changed, the goal remains the same: to inform, persuade, and mobilize voters. By understanding the strengths and limitations of each medium, both parties and citizens can navigate this evolving landscape more effectively, ensuring that the essence of democracy—informed participation—endures.

Should I Switch Political Parties? Evaluating Values, Policies, and Alignment

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$18.32 $39.95

Party Structures: Modern parties are centralized, professionalized, unlike 1860's loose, localized organizations

In the 1860s, political parties were often little more than loose coalitions of local interests, with minimal central authority and a heavy reliance on grassroots organization. These parties were characterized by their decentralized nature, where state and local leaders held significant power, and national party structures were relatively weak. For instance, the Republican and Democratic parties of the time were more like federations of state parties, each with its own agenda and priorities, rather than unified national organizations. This decentralization meant that party platforms and strategies could vary widely from one region to another, reflecting local concerns rather than a cohesive national vision.

Contrast this with the modern political party, which is a highly centralized and professionalized machine. Today’s parties operate with a clear hierarchy, where national committees wield substantial control over messaging, fundraising, and candidate selection. The Democratic National Committee (DNC) and the Republican National Committee (RNC) are prime examples, serving as the nerve centers for their respective parties. These organizations employ full-time staff, data analysts, and communications experts, ensuring a level of coordination and efficiency that was unimaginable in the 1860s. This centralization allows modern parties to project a consistent brand and message across the country, crucial in an era of national media and instant communication.

The professionalization of party structures is another key differentiator. In the 1860s, party work was largely volunteer-driven, with local notables and activists taking the lead. Today, parties are staffed by career professionals who specialize in areas like campaign management, polling, and digital strategy. For example, the use of microtargeting—a technique where voter data is analyzed to tailor messages to specific demographics—is now standard practice. This level of sophistication requires expertise that only a professionalized party apparatus can provide. As a result, modern parties are far more effective at mobilizing resources and adapting to the rapidly changing political landscape.

However, this evolution is not without its drawbacks. The centralized and professionalized nature of modern parties can alienate grassroots activists, who may feel sidelined by the top-down decision-making process. In the 1860s, local party leaders had a direct say in shaping party policies and selecting candidates, fostering a sense of ownership and engagement. Today, while parties are more efficient, they risk becoming disconnected from the very communities they aim to represent. Striking a balance between centralization and local autonomy remains a challenge for contemporary political organizations.

To illustrate, consider the role of party conventions. In the 1860s, conventions were raucous affairs where delegates genuinely debated and decided on platforms and candidates. Today, conventions are largely scripted events, with outcomes often predetermined by party leadership. While this ensures a smoother process, it also diminishes the role of rank-and-file members. For those looking to engage with their party, understanding this dynamic is crucial. Participating in local caucuses, attending town halls, and joining party committees are practical ways to influence the process, even within a highly centralized system. By doing so, individuals can help bridge the gap between the professionalized party structure and the grassroots energy that remains essential to political success.

Capitalizing Political Parties: AP Style Rules and Guidelines Explained

You may want to see also

Policy Complexity: Today's platforms address global issues, compared to 1860's narrow, domestically focused agendas

Contemporary political parties operate in a world where policy agendas are inextricably linked to global issues, a stark contrast to the 1860s when platforms were predominantly, if not exclusively, domestically focused. The 1860 U.S. presidential election, for instance, revolved around slavery, states' rights, and economic policies like tariffs—issues that, while monumental, were confined to the nation's borders. Today, a party’s platform must address transnational challenges such as climate change, cybersecurity, and pandemic response, which demand international cooperation and cross-border solutions. This shift reflects not only the evolution of political priorities but also the interconnectedness of the modern world.

Consider the issue of climate change, a defining challenge of the 21st century. Contemporary political parties must propose policies that align with global agreements like the Paris Accord, balancing national interests with international commitments. In contrast, the 1860s political discourse was devoid of such considerations. For example, the Republican Party’s platform in 1860 focused on preventing the expansion of slavery into new territories, a concern entirely within the U.S. geopolitical sphere. Today, a party’s stance on environmental policy is scrutinized not just for its domestic impact but for its contribution to a global effort.

This expansion in policy scope introduces a layer of complexity that 19th-century parties never faced. Modern platforms must navigate the tension between national sovereignty and global responsibility, often requiring nuanced positions that appeal to both local constituents and international allies. For instance, a party advocating for stricter emissions standards must also address the economic implications for domestic industries, a balancing act that would have been foreign to 1860s politicians. This complexity is further amplified by the need to communicate these policies in a globally connected media landscape, where every statement can have international repercussions.

Practical implementation of global policies also differs significantly. In the 1860s, a party’s success was measured by its ability to enact legislation within its own borders. Today, effective policy-making often involves coordinating with multinational organizations, negotiating trade agreements, and participating in global forums. For example, a contemporary party’s healthcare platform might include strategies for collaborating with the World Health Organization to address pandemics, a level of international engagement unimaginable in the 1860s. This requires politicians to possess not just domestic policy expertise but also a deep understanding of global systems and dynamics.

The takeaway is clear: the policy complexity of contemporary political parties is a direct result of their engagement with global issues, a realm entirely absent from 1860s agendas. This evolution demands a more sophisticated approach to governance, one that acknowledges the interdependence of nations and the shared challenges they face. While the 1860s parties focused on building and preserving a nation, today’s parties must think in terms of sustaining a planet. This shift is not just a matter of scale but of perspective, requiring politicians and voters alike to embrace a worldview that transcends borders.

The Rise of New Political Parties in the 1820s Era

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Contemporary political parties often encompass a broader range of ideological diversity within their ranks, reflecting modern societal complexities. In 1860, parties were more ideologically homogeneous, primarily focused on issues like slavery, states' rights, and economic policies tied to industrialization.

Technology is central to modern political parties, enabling rapid communication, fundraising, and mobilization through social media, email, and digital advertising. In 1860, parties relied on newspapers, pamphlets, and in-person rallies, which were slower and more localized.

Modern parties use data-driven strategies, polling, and targeted messaging to engage voters, often focusing on specific demographics. In 1860, voter engagement was more personal, relying on local party leaders, public speeches, and community networks.

Today, women and minorities play significant roles in political parties, holding leadership positions and shaping policies. In 1860, women had no voting rights, and minorities, particularly African Americans, were largely excluded from political participation, especially in the South.

Modern parties rely on large-scale fundraising through digital platforms, corporate donations, and small individual contributions. In 1860, fundraising was more localized, often dependent on wealthy patrons, party events, and direct contributions from members.