The evolution of political parties in the United States is a dynamic and complex narrative that reflects the nation's shifting ideologies, societal changes, and responses to historical events. Emerging in the late 18th century, the first major parties, the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, were shaped by debates over the Constitution and the role of government. Over time, these parties gave way to the Democratic and Whig parties, which later evolved into the modern Democratic and Republican parties during the mid-19th century. Issues such as slavery, economic policies, and states' rights fueled partisan divisions, while the Civil War and Reconstruction further reshaped party alignments. The 20th century saw the rise of progressive movements, the New Deal coalition, and the realignment of the South from Democratic to Republican dominance. Today, the two-party system remains dominant, though third parties and independent movements continue to influence political discourse, reflecting the enduring adaptability and fragmentation of American political identity.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Founding Period (1790s) | Federalist Party (pro-central government) vs. Democratic-Republican Party (states' rights, agrarian focus) |

| Second Party System (1820s-1850s) | Democratic Party (states' rights, limited government) vs. Whig Party (national bank, industrialization) |

| Civil War Era (1850s-1860s) | Republican Party emerges (anti-slavery, national unity) vs. Democrats (split over slavery) |

| Post-Civil War (1860s-1900s) | Republicans dominate (reconstruction, industrialization) vs. Democrats (solid South, agrarian interests) |

| Progressive Era (early 1900s) | Both parties adopt progressive reforms (trust-busting, worker rights) |

| New Deal Era (1930s-1940s) | Democrats shift left (social welfare, government intervention) vs. Republicans (limited government) |

| Civil Rights Era (1950s-1960s) | Democrats embrace civil rights; Southern Democrats shift to Republican Party (Southern Strategy) |

| Modern Era (1980s-Present) | Republicans (conservative, free market, social conservatism) vs. Democrats (liberal, social justice, government intervention) |

| Third Parties | Limited success (e.g., Libertarians, Greens) but influence policy debates |

| Polarization | Increasing ideological divide between parties since the 1990s |

| Demographic Shifts | Democrats gain urban, minority, and youth voters; Republicans dominate rural and white working-class areas |

| Key Issues | Democrats focus on healthcare, climate change, and equality; Republicans emphasize tax cuts, national security, and traditional values |

Explore related products

$68.37 $74

$35.53 $61.99

What You'll Learn

- Founding Era Parties: Federalists vs. Democratic-Republicans, shaping early U.S. political ideology and governance

- Second Party System: Whigs and Democrats dominate, focusing on economic policies and regional interests

- Civil War Impact: Republican Party rises, replacing Whigs, and reshaping national politics

- Progressive Era Shifts: Third parties emerge, influencing major parties on reform and social issues

- Modern Two-Party System: Democrats and Republicans solidify dominance, adapting to changing demographics and issues

Founding Era Parties: Federalists vs. Democratic-Republicans, shaping early U.S. political ideology and governance

The Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties, emerging in the 1790s, were the first to define American political ideology and governance. These parties, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, respectively, clashed over the role of the federal government, economic policy, and the interpretation of the Constitution. Their debates laid the groundwork for the two-party system and continue to influence modern political discourse.

Step 1: Understanding Federalist Principles

Federalists, championed by Hamilton, advocated for a strong central government, believing it essential for national stability and economic growth. They supported a national bank, tariffs, and assumed state debts to foster industrial development. Their vision was rooted in a loose interpretation of the Constitution, often referred to as "implied powers." For instance, Hamilton’s financial plans aimed to solidify federal authority and attract investment, setting a precedent for active government intervention in the economy.

Step 2: Contrasting Democratic-Republican Ideals

Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans, in stark contrast, feared centralized power and championed states’ rights and agrarian interests. They viewed Hamilton’s policies as elitist and a threat to individual liberty. Strict constructionists, they argued the Constitution should be interpreted literally, limiting federal authority. Their emphasis on decentralized governance and agrarian democracy resonated with small farmers and frontier settlers, shaping early populist movements.

Caution: The Impact of Polarization

The rivalry between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans often led to extreme polarization, exemplified by the bitter election of 1800. While their debates fostered robust political discourse, they also highlighted the dangers of ideological rigidity. For instance, Federalists’ Alien and Sedition Acts, aimed at suppressing dissent, were seen as tyrannical by Democratic-Republicans, sparking a national debate on free speech and government overreach.

The Federalist-Democratic-Republican divide established enduring themes in American politics: the balance between federal and state power, the role of government in the economy, and the tension between individual liberty and national unity. Today, echoes of these debates can be seen in discussions on healthcare, taxation, and federal authority. Understanding this foundational era provides a lens to analyze contemporary political conflicts and the evolution of party ideologies.

Practical Tip: To grasp the nuances of this era, explore primary sources like Hamilton’s *Federalist Papers* and Jefferson’s inaugural addresses. These documents offer direct insight into the minds of the founders and the principles that shaped early American governance.

Understanding Traditional Political Culture: Values, Norms, and Historical Roots

You may want to see also

Second Party System: Whigs and Democrats dominate, focusing on economic policies and regional interests

The Second Party System, emerging in the 1830s and lasting until the 1850s, was defined by the rivalry between the Whig Party and the Democratic Party. This era marked a shift from the earlier focus on states’ rights and federal power to a more nuanced debate over economic policies and regional interests. The Whigs, led by figures like Henry Clay, championed a program of national development, including infrastructure projects, tariffs to protect American industries, and a strong national bank. In contrast, the Democrats, under Andrew Jackson and later Martin Van Buren, emphasized limited government, states’ rights, and opposition to centralized banking, appealing particularly to farmers and the working class.

Consider the economic policies of these parties as a prescription for national growth, each with its own "dosage" of federal intervention. The Whigs’ American System, akin to a high-dose treatment, aimed to stimulate the economy through aggressive federal spending on roads, canals, and railroads. Their support for tariffs, such as the Tariff of 1842, acted as a protective shield for domestic industries, much like an antibiotic warding off foreign competition. Democrats, however, prescribed a lower-dose approach, advocating for a laissez-faire economy and opposing federal projects they deemed wasteful. Their hard money policies, tied to the gold and silver standard, were a financial equivalent of a steady, conservative diet, avoiding the inflationary risks of paper currency.

Regional interests further polarized these parties, creating a political landscape akin to a patchwork quilt, each piece representing distinct economic and cultural priorities. The Whigs found their strongest support in the Northeast and Midwest, regions benefiting from industrialization and internal improvements. For example, the construction of the Erie Canal in New York exemplified the Whig vision of progress, linking agricultural markets to urban centers. Democrats, meanwhile, dominated the South and West, where agrarian economies feared federal overreach and tariffs that raised the cost of imported goods. The Nullification Crisis of 1832–1833, sparked by South Carolina’s resistance to federal tariffs, underscored the regional tensions that the Second Party System navigated.

A comparative analysis reveals how these parties mirrored the age categories of a developing nation. The Whigs, like ambitious young adults, sought to build and expand, investing in the future through bold initiatives. Democrats, by contrast, resembled cautious elders, prioritizing stability and local control, wary of the risks inherent in rapid change. This generational divide was not just ideological but practical, as policies like the Whigs’ national bank proposal clashed with the Democrats’ preference for decentralized financial systems.

In practice, understanding this era offers a useful guide for interpreting modern political debates. For instance, contemporary arguments over infrastructure spending or trade policies echo the Whig-Democratic divide. To apply this historically: if you’re advocating for federal investment in renewable energy, you’re channeling Whig principles; if you oppose such measures as government overreach, you align with Democratic skepticism. The takeaway? The Second Party System’s focus on economic policies and regional interests remains a blueprint for analyzing how political parties evolve to address the needs of a diverse nation.

Greek Theatre's Political Power: Shaping Democracy Through Performance

You may want to see also

Civil War Impact: Republican Party rises, replacing Whigs, and reshaping national politics

The American Civil War (1861–1865) acted as a political catalyst, dismantling the Whig Party and propelling the Republican Party into national prominence. The Whigs, already fractured over slavery and economic policies, collapsed under the weight of their inability to present a unified stance on the Union’s future. In contrast, the Republicans, founded in 1854, seized the moment by adopting a clear anti-slavery platform, attracting abolitionists, northern industrialists, and former Whigs disillusioned with their party’s indecision. This strategic positioning allowed the Republicans to emerge as the dominant force in post-war politics, reshaping the nation’s ideological landscape.

Consider the 1860 presidential election as a case study in this transformation. Abraham Lincoln, the Republican nominee, won without a single Southern electoral vote, signaling the party’s northern base and its commitment to limiting slavery’s expansion. His victory was not just a personal triumph but a validation of the Republican Party’s ability to mobilize voters around a cohesive vision. Meanwhile, the Whigs’ absence from the ballot highlighted their irrelevance, as their moderate stance on slavery failed to resonate in an increasingly polarized nation. This election marked the beginning of the Republicans’ rise and the Whigs’ descent into political obscurity.

The Civil War’s aftermath further solidified the Republicans’ dominance through their leadership in Reconstruction. The party championed policies like the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, which abolished slavery, granted citizenship to freedmen, and ensured voting rights regardless of race. These measures not only redefined the nation’s moral and legal framework but also established the Republicans as the party of progress and equality in the eyes of many Northerners. By contrast, the Democrats, who opposed these reforms, were branded as the party of resistance, limiting their appeal outside the South.

However, the Republicans’ success was not without challenges. Internal divisions over Reconstruction policies and economic strategies, such as tariffs and currency standards, threatened party unity. Yet, their ability to adapt and maintain control of the presidency for most of the post-war period demonstrated their resilience. By the late 19th century, the Republicans had become the nation’s leading party, while the Whigs were a historical footnote. This shift underscores how the Civil War not only reshaped the nation but also redefined its political parties, with the Republicans emerging as the architects of a new era.

Practical takeaways from this evolution include the importance of clear, principled stances in times of crisis. The Republicans’ anti-slavery platform provided a moral and political anchor during the Civil War, attracting diverse supporters. Additionally, their ability to translate wartime leadership into post-war policy initiatives ensured their longevity. For modern political strategists, this history serves as a reminder that parties must align their values with the nation’s evolving priorities to remain relevant. The Republicans’ rise from obscurity to dominance offers a blueprint for how parties can capitalize on historical moments to reshape national politics.

Jackson's Presidency: The Impact of Political Parties - Harmful or Helpful?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Progressive Era Shifts: Third parties emerge, influencing major parties on reform and social issues

The Progressive Era, spanning the late 19th and early 20th centuries, marked a seismic shift in American politics, characterized by the rise of third parties that forced major parties to confront pressing reform and social issues. The Populist Party, for instance, emerged in the 1890s, championing agrarian interests and economic reforms like the graduated income tax and direct election of senators. Though short-lived, its platform laid the groundwork for future progressive movements, demonstrating how third parties could amplify marginalized voices and push systemic change.

Consider the role of the Socialist Party of America, led by figures like Eugene V. Debs, which gained traction by advocating for workers’ rights, women’s suffrage, and public ownership of utilities. While it never won a presidential election, its influence on Democratic and Republican platforms was undeniable. For example, the Socialists’ push for labor protections and social welfare programs foreshadowed Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies. This illustrates how third parties often serve as incubators for ideas that major parties later adopt, albeit in diluted or modified forms.

The Progressive Party, colloquially known as the Bull Moose Party, offers another compelling case study. Founded by Theodore Roosevelt in 1912 after he split from the Republican Party, it championed antitrust legislation, women’s suffrage, and environmental conservation. Though Roosevelt lost the election, his campaign forced both major parties to address progressive reforms. By 1920, women’s suffrage became law, and antitrust measures gained bipartisan support, proving that third-party challenges can accelerate policy shifts even without electoral victory.

To understand the mechanics of this influence, examine how third parties create a “policy bidding war.” When a third party gains traction, major parties often co-opt its platform to retain voters. For instance, the Prohibition Party’s relentless advocacy for temperance eventually led to the 18th Amendment, though the party itself remained minor. Similarly, today’s Green Party has pushed Democrats to prioritize climate change, showing how third parties can act as catalysts for mainstream policy adoption.

In practical terms, third parties during the Progressive Era taught us that their value lies not just in winning elections but in reshaping the political discourse. Activists and reformers can leverage this by strategically aligning with or forming third parties to spotlight neglected issues. For example, if you’re advocating for a specific reform—say, campaign finance reform—consider supporting or joining a third party that prioritizes it. This amplifies your message and forces major parties to respond, even if incrementally. The Progressive Era’s legacy underscores that third parties are not mere spoilers but essential drivers of democratic evolution.

Rev. James Polite: Unveiling the Legacy of a Visionary Leader

You may want to see also

Modern Two-Party System: Democrats and Republicans solidify dominance, adapting to changing demographics and issues

The modern two-party system in the United States is a testament to the adaptability of the Democratic and Republican parties, which have not only survived but thrived amidst shifting demographics, emerging issues, and cultural transformations. Since the mid-20th century, these parties have solidified their dominance by recalibrating their platforms, messaging, and coalitions to reflect the evolving priorities of the American electorate. For instance, the Democratic Party’s shift from a predominantly Southern, conservative base to a diverse coalition of urban, minority, and progressive voters exemplifies this adaptability. Similarly, the Republican Party’s transition from a moderate, Northeastern stronghold to a conservative, rural, and evangelical-aligned force underscores its ability to pivot in response to changing political landscapes.

To understand this dynamic, consider the strategic realignment of both parties around key issues. Democrats, once divided on civil rights, unified behind a progressive agenda that championed racial equality, LGBTQ+ rights, and environmental sustainability. This shift was crucial in attracting younger voters and minority groups, who now form the backbone of the party’s electoral base. Republicans, meanwhile, doubled down on economic conservatism, social traditionalism, and national security, appealing to rural and suburban voters wary of cultural and economic change. These adaptations were not accidental but deliberate, driven by data-driven campaigns, targeted messaging, and the rise of political consulting as a science.

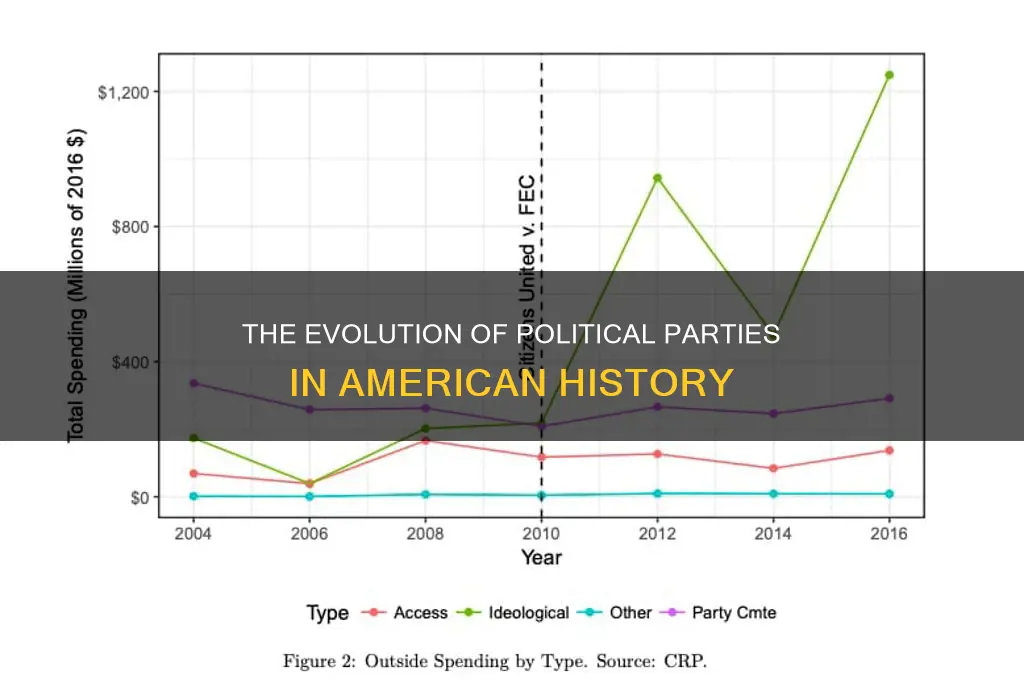

A comparative analysis reveals how both parties have exploited structural advantages to maintain dominance. The winner-take-all electoral system in most states discourages third-party viability, forcing voters into a binary choice. Additionally, the parties’ control over primaries and fundraising mechanisms ensures that ideological purity is rewarded, marginalizing moderates and independents. However, this system is not without risks. The increasing polarization it fosters has led to legislative gridlock and voter disillusionment, raising questions about long-term sustainability.

For those seeking to navigate this system, practical tips include understanding the parties’ evolving platforms and identifying where your values align. Democrats currently emphasize healthcare expansion, climate action, and social justice, while Republicans focus on tax cuts, deregulation, and cultural conservatism. Engaging in local politics, where party influence is more malleable, can also provide opportunities to shape policy. Caution, however, is advised when aligning too closely with party orthodoxy, as both parties’ stances can shift rapidly in response to electoral pressures.

In conclusion, the modern two-party system is a dynamic, ever-changing entity shaped by the interplay of demographics, issues, and strategic adaptation. While Democrats and Republicans have mastered the art of survival in this system, their dominance is not guaranteed. Voters, activists, and policymakers must remain vigilant, ensuring that the parties continue to evolve in ways that serve the broader public interest rather than merely perpetuating their own power.

Exploring Ireland's Political Landscape: A Comprehensive Party Count Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Democratic Party originated in the 1820s from the Democratic-Republican Party, led by figures like Andrew Jackson. It initially championed states' rights, limited federal government, and agrarian interests. Over time, it shifted to support labor rights, civil rights, and social welfare programs, particularly during the New Deal era under Franklin D. Roosevelt. Today, it is associated with progressive policies, social liberalism, and a focus on economic equality.

The Republican Party was founded in 1854 by anti-slavery activists, former Whigs, and Free Soil members in response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which allowed slavery in new territories. Its core principles included opposing the expansion of slavery, promoting economic modernization, and supporting national unity. Abraham Lincoln became the first Republican president in 1860, and the party played a central role in the abolition of slavery during the Civil War.

Third parties in the U.S. often arise to address issues or ideologies not fully represented by the Democratic or Republican Parties. For example, the Libertarian Party, founded in 1971, advocates for minimal government intervention, individual liberty, and free markets. The Green Party, established in the 1980s, focuses on environmental sustainability, social justice, and grassroots democracy. While third parties rarely win national elections due to the two-party system, they influence political discourse and push major parties to address their concerns.