The formation of political parties in the United States is deeply rooted in the nation's early struggles to define its governance and identity. Emerging in the late 18th century, the first political factions—the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans—were born out of differing visions for the country's future. Federalists, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, advocated for a strong central government and economic modernization, while Democratic-Republicans, under Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, championed states' rights, agrarian interests, and a more limited federal role. These divisions, fueled by debates over the Constitution, economic policies, and foreign relations, laid the groundwork for the two-party system. Over time, these early parties evolved, and new ones emerged, reflecting shifting societal values, regional interests, and ideological battles. The enduring structure of political parties in the U.S. remains a testament to the ongoing tension between unity and diversity in American democracy.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Historical Context | Political parties in the U.S. emerged from early factions like Federalists and Anti-Federalists during the late 18th century. |

| Founding Principles | Parties formed around differing views on government power, economic policies, and interpretation of the Constitution. |

| Key Figures | Early leaders like Alexander Hamilton (Federalist) and Thomas Jefferson (Democratic-Republican) played pivotal roles. |

| Evolution Over Time | Parties evolved through issues like slavery, industrialization, and civil rights, leading to the modern two-party system. |

| Ideological Divisions | Parties are broadly divided into conservative (Republican) and liberal (Democratic) ideologies. |

| Geographic Influence | Regional differences (e.g., Southern Democrats, Northern Republicans) shaped party identities. |

| Electoral Systems | The winner-takes-all electoral system encourages a two-party dominance. |

| Interest Groups | Parties align with specific interest groups (e.g., labor unions, business lobbies) to gain support. |

| Media and Communication | Advances in media (newspapers, TV, internet) have influenced party messaging and mobilization. |

| Third Parties | Smaller parties (e.g., Libertarian, Green) exist but face barriers due to the two-party system. |

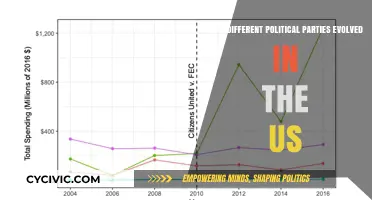

| Modern Challenges | Polarization, gerrymandering, and campaign financing impact party dynamics in the 21st century. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Historical origins of political parties

The roots of political parties can be traced back to ancient civilizations, where factions and alliances formed around influential leaders or ideologies. In Rome, for instance, the Optimates and Populares emerged as early precursors to political parties, representing the interests of the aristocracy and the common people, respectively. These groups laid the groundwork for organized political competition, demonstrating that the human tendency to coalesce around shared beliefs is timeless. Understanding these ancient origins provides a lens through which we can analyze the development of modern political parties.

The formalization of political parties as we know them today began during the Enlightenment and the Age of Revolution. In 18th-century Britain, the Whigs and Tories crystallized as distinct factions, advocating for opposing views on monarchy, religion, and governance. The Whigs supported constitutional monarchy and religious tolerance, while the Tories favored royal prerogative and Anglican supremacy. This period marked the transition from informal alliances to structured parties with clear platforms, a model that would influence political systems globally. The British example illustrates how societal divisions and ideological debates are the fertile soil from which parties grow.

Across the Atlantic, the United States offers a unique case study in party formation. The Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties emerged in the late 18th century, reflecting deep disagreements over the role of the federal government and the interpretation of the Constitution. Alexander Hamilton’s Federalists championed a strong central government and industrialization, while Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans advocated for states’ rights and agrarian interests. These early parties were not just political organizations but also vehicles for shaping national identity. Their rivalry highlights how parties often form in response to foundational questions about a nation’s direction and values.

In France, the aftermath of the Revolution saw the rise of political clubs like the Jacobins and Girondins, which functioned as proto-parties during a tumultuous period of political upheaval. These groups mobilized public opinion and competed for control of the revolutionary government, showcasing the role of grassroots movements in party formation. However, it was the 19th century that solidified party systems in Europe, as industrialization and democratization expanded the electorate. Parties like the Conservatives, Liberals, and Socialists emerged, each representing distinct social classes and economic interests. This era underscores the importance of socioeconomic factors in driving party creation and differentiation.

A comparative analysis of these historical examples reveals a common thread: political parties arise from divisions within society, whether rooted in ideology, class, or regional interests. They serve as mechanisms for organizing and expressing these divisions, channeling them into the political process. However, the formation of parties is not without risks. Early party systems often exacerbated conflicts, as seen in the U.S. Civil War or the French Revolution, where partisan polarization led to violence. To mitigate such risks, modern democracies emphasize checks and balances, inclusive representation, and the rule of law. By studying these historical origins, we gain insights into how parties can both unite and divide societies, offering lessons for fostering healthier political competition today.

Understanding the Green Party's Core Values and Environmental Policies

You may want to see also

Key figures and founders of early parties

The formation of early political parties in the United States was deeply influenced by key figures whose visions and actions shaped the nation's political landscape. Among these, Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton stand out as the intellectual and ideological architects of the first major parties. Jefferson, a champion of states' rights and agrarian interests, founded the Democratic-Republican Party, which advocated for limited federal government and individual liberties. Hamilton, on the other hand, led the Federalist Party, promoting a strong central government and economic modernization. Their rivalry, encapsulated in debates over the Constitution and economic policies, laid the groundwork for the two-party system.

Consider the contrasting leadership styles of these founders. Jefferson's approach was inclusive, appealing to farmers and the common man, while Hamilton's was elitist, favoring bankers and industrialists. This divide wasn't just philosophical; it was practical. Jefferson's party organized grassroots campaigns, while Hamilton's relied on established networks of power. For instance, Jefferson's supporters distributed pamphlets and held public meetings, whereas Hamilton's allies used their influence in Congress and financial institutions to advance their agenda. These methods became templates for future party-building efforts.

A lesser-known but equally influential figure is Aaron Burr, whose role in the early Republican Party highlights the complexities of party formation. Burr's political acumen and strategic maneuvering, particularly in the 1800 election, demonstrated the importance of tactical skill in party politics. His infamous duel with Hamilton also underscores the personal rivalries that often drove early party dynamics. While Burr is often remembered for this dramatic event, his contributions to party organization, such as building coalitions across states, were pivotal in the party's early success.

To understand the impact of these founders, examine their legacies in modern politics. Jefferson's emphasis on states' rights resonates in today's conservative movements, while Hamilton's vision of a strong federal government aligns with contemporary liberal policies. For those studying party formation, analyzing these figures provides a roadmap. Start by identifying core ideologies, then study how they mobilized supporters and navigated conflicts. Practical tip: When forming a political group, define your core values clearly and build a diverse coalition, as Jefferson did, to ensure broad appeal.

Finally, the cautionary tale of early party founders lies in their inability to foresee the long-term consequences of their actions. Hamilton's financial policies, for example, while stabilizing the economy, sowed seeds of inequality that persist today. Similarly, Jefferson's idealized vision of agrarian democracy struggled to address issues like slavery. For modern organizers, this serves as a reminder: balance idealism with pragmatism. Assess how your party's actions will impact future generations, and be prepared to adapt your strategies to address unforeseen challenges.

How Political Parties Focus on Key Issues and Voter Engagement

You may want to see also

Evolution of party ideologies over time

Political parties, much like living organisms, evolve in response to their environments. The ideologies that define them are not static; they shift, adapt, and sometimes undergo radical transformations over time. Consider the Democratic Party in the United States. Founded in the early 19th century as a coalition of farmers, workers, and Southern elites, it initially championed states' rights and limited federal government. Fast forward to the 20th century, and the party became the standard-bearer for civil rights, social welfare programs, and progressive policies. This evolution wasn’t linear—it was shaped by historical events like the Great Depression, the Civil Rights Movement, and shifting demographics. Such transformations illustrate how party ideologies are not immutable but are continually reshaped by societal pressures and political expediency.

To understand this evolution, examine the role of crises in forcing ideological shifts. For instance, the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom underwent a dramatic change under Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s. Prior to her leadership, the party was characterized by a more paternalistic, one-nation conservatism. Thatcher, however, introduced neoliberal policies—deregulation, privatization, and reduced government intervention—that redefined the party’s ideology. This shift wasn’t merely a top-down imposition; it was a response to economic stagnation and a desire for radical change. Similarly, in Germany, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) moved from a strictly socialist platform to a more centrist, Third Way approach under Gerhard Schröder in the late 1990s. These examples highlight how external crises and internal leadership can catalyze ideological evolution, often leaving lasting imprints on a party’s identity.

A comparative analysis reveals that ideological evolution often occurs through the absorption or rejection of fringe movements. In the United States, the Republican Party’s embrace of the Tea Party movement in the late 2000s shifted its focus toward fiscal conservatism and anti-government sentiment. Conversely, the Democratic Party’s recent incorporation of progressive ideas, such as the Green New Deal, reflects the influence of younger, more activist-driven factions. This dynamic isn’t unique to the U.S.; in France, the National Rally (formerly the National Front) under Marine Le Pen softened its extreme-right rhetoric to appeal to a broader electorate, marking a strategic ideological shift. Such adaptations demonstrate how parties co-opt or resist external movements to remain relevant in a changing political landscape.

Practical takeaways for understanding ideological evolution include tracking policy platforms over time and analyzing voter demographics. For instance, the rise of environmental concerns has pushed parties across the globe to incorporate green policies into their agendas, regardless of their traditional stances. In Canada, the Liberal Party under Justin Trudeau has emphasized climate action, while in Australia, the Labor Party has made renewable energy a cornerstone of its platform. These shifts aren’t random; they reflect changing public priorities. To trace such evolution, start by comparing party manifestos from different decades, noting key policy changes. Additionally, examine how parties target specific age groups—for example, younger voters often drive progressive shifts, while older voters may anchor more traditional ideologies. By focusing on these metrics, one can predict future ideological trends and understand the forces driving them.

Finally, it’s crucial to recognize that ideological evolution is not always smooth or universally accepted. Internal factions within parties often resist change, leading to fractures or splinter groups. The Labour Party in the UK, for instance, experienced significant internal conflict during Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership, as his left-wing policies alienated centrist members. Similarly, the Republican Party in the U.S. has grappled with divisions between Trumpist populism and traditional conservatism. These tensions underscore the challenges of ideological transformation. Parties must balance the need to adapt with the risk of alienating core supporters. For observers and participants alike, this means staying attuned to both the external pressures driving change and the internal dynamics that can either facilitate or hinder it.

How Racial Bias Derailed Post-Civil War Reconstruction Efforts in America

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$12.76 $19.95

Role of elections in shaping party systems

Elections serve as the crucible in which party systems are forged, tested, and transformed. They are not merely a mechanism for selecting leaders but a dynamic process that shapes the very structure of political parties. Consider the United States, where the two-party system emerged not from constitutional design but from the repeated winnowing effect of winner-take-all elections. Over time, smaller parties struggled to secure representation, while the Democratic and Republican parties adapted to absorb diverse interests, creating broad coalitions that dominate the political landscape. This example illustrates how electoral rules and voter behavior can inadvertently consolidate power within a few dominant parties.

To understand this process, examine the role of electoral systems. Proportional representation, for instance, encourages multi-party systems by allocating seats based on vote share, allowing smaller parties to gain representation. In contrast, first-past-the-post systems, like those in the U.S. and U.K., favor larger parties by rewarding the candidate with the most votes in each district, often marginalizing smaller factions. This structural difference highlights how elections act as a filter, determining which parties survive and thrive based on their ability to mobilize voters and secure seats.

However, elections do more than reflect existing party structures—they also drive party evolution. Parties must adapt their platforms, strategies, and identities to appeal to shifting voter demographics and priorities. For example, the rise of green parties in Europe was fueled by elections that provided a platform for environmental concerns, forcing established parties to incorporate these issues into their agendas. This adaptive process ensures that party systems remain responsive to societal changes, though it can also lead to ideological convergence or polarization, depending on the electoral context.

A practical takeaway for political strategists and reformers is that altering electoral rules can intentionally reshape party systems. Introducing ranked-choice voting, for instance, can reduce the spoiler effect and encourage greater party diversity by allowing voters to express preferences beyond their first choice. Similarly, lowering the vote threshold for parliamentary representation can give smaller parties a fighting chance. These reforms demonstrate how elections are not just a reflection of party systems but a tool for actively sculpting them.

In conclusion, elections are the engine of party system formation and transformation. They filter, adapt, and reshape political parties through mechanisms that reward certain strategies and penalize others. By understanding this dynamic, policymakers and citizens can harness the power of elections to build party systems that better reflect societal diversity and democratic ideals. Whether through structural reforms or strategic adaptation, the role of elections in shaping party systems is both profound and actionable.

Early Political Parties' Fear of Strong Federal Government Explained

You may want to see also

Influence of social movements on party formation

Social movements have long been catalysts for political party formation, often emerging as a response to societal grievances that existing parties fail to address. For instance, the abolitionist movement in the 19th-century United States laid the groundwork for the Republican Party, which was founded on the principle of opposing the expansion of slavery. This example illustrates how movements can crystallize public sentiment into a cohesive political force, pushing for systemic change through the creation of new parties. When a movement gains momentum, it often identifies the need for a dedicated platform to translate its ideals into policy, thus bridging the gap between activism and governance.

To understand this process, consider the steps involved in transforming a social movement into a political party. First, the movement must articulate a clear and unifying vision that resonates with a broad audience. Second, it needs to build organizational structures capable of mobilizing resources, recruiting candidates, and engaging voters. Third, it must navigate the legal and institutional barriers to party registration and electoral participation. For example, the Green Party in Germany evolved from the environmental movement of the 1970s by systematically addressing these steps, eventually becoming a significant political force. This structured approach ensures that the movement’s energy is channeled effectively into party formation.

However, the transition from movement to party is not without challenges. Movements often thrive on decentralized, grassroots energy, which can clash with the hierarchical and strategic demands of party politics. Take the Occupy Wall Street movement, which, despite its global impact, failed to coalesce into a formal political party due to internal disagreements and a lack of clear leadership. This cautionary tale highlights the importance of balancing ideological purity with pragmatic political organization. Movements must be willing to adapt their tactics and structures if they aim to influence policy through party formation.

A comparative analysis of successful cases reveals that movements with strong local networks and clear policy agendas are more likely to spawn viable parties. For instance, the women’s suffrage movement in the early 20th century not only secured voting rights but also inspired the formation of feminist-aligned parties in several countries. In contrast, movements that remain fragmented or fail to translate their demands into actionable policies often struggle to make the leap. Practical tips for movement leaders include fostering alliances with existing political actors, leveraging technology for outreach, and prioritizing voter education to build a sustainable base.

Ultimately, the influence of social movements on party formation underscores the dynamic interplay between grassroots activism and formal politics. Movements provide the spark, but it is the strategic transformation of that energy into a party structure that ensures lasting impact. By studying historical examples and understanding the challenges, contemporary movements can chart a path toward meaningful political representation. This process is not just about creating a new party but about reshaping the political landscape to reflect the aspirations of those who demand change.

Balancing the Polls: Do Poll Workers Need Bipartisan Representation?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The first political parties in the United States emerged during George Washington's presidency in the 1790s. The Federalist Party, led by Alexander Hamilton, supported a strong central government and industrialization, while the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson, advocated for states' rights and agrarian interests. These divisions arose from debates over the Constitution and economic policies.

Regional differences significantly influenced the formation of political parties. For example, the North favored industrialization and tariffs, aligning with the Whig Party and later the Republican Party, while the South emphasized agriculture and states' rights, aligning with the Democratic Party. These regional interests shaped party platforms and alliances.

The issue of slavery led to the fragmentation of existing parties and the creation of new ones in the mid-19th century. The Whig Party collapsed due to internal disagreements over slavery, and the Republican Party was formed in 1854 to oppose the expansion of slavery. This realignment culminated in the Civil War and solidified the modern two-party system.

Political parties evolve due to changing societal values, demographic shifts, and new issues. For instance, the Democratic Party shifted from supporting slavery in the 19th century to advocating civil rights in the 20th century. Such evolution reflects the need for parties to adapt to remain relevant, often leading to internal reforms or the emergence of new factions.