The Constitution of the United States has a two-step process for amendments, which must be proposed and ratified before becoming operative. The U.S. Congress can propose an amendment with a two-thirds majority vote in the Senate and House of Representatives, or a national convention can be called by Congress on the application of two-thirds of state legislatures. Once proposed, an amendment becomes part of the Constitution when it is ratified by three-fourths of the states. Since 1789, there have been nearly 12,000 proposals to amend the Constitution, with 27 amendments successfully becoming part of the Constitution.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Authority to amend the Constitution | Article V of the Constitution |

| Amendment proposal | By Congress with a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate or by a constitutional convention called for by two-thirds of the state legislatures |

| Amendment ratification | Three-fourths of the States (38 of 50 States) |

| Number of proposed amendments | More than 11,000 |

| Number of ratified amendments | 27 |

| First 10 amendments | Known as the Bill of Rights, proposed by Congress on September 25, 1789, and ratified on December 15, 1791 |

| Amendment process | The Archivist of the United States administers the ratification process, with support from the Director of the Federal Register |

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

What You'll Learn

The process of proposing amendments

The first method, which has been utilised since the founding of the Constitution, involves Congress proposing an amendment in the form of a joint resolution. This resolution is forwarded directly to the National Archives and Records Administration's (NARA) Office of the Federal Register (OFR) for processing and publication. The OFR adds legislative history notes and publishes the resolution in slip law format, as well as assembling an information package for the states.

The Archivist of the United States then submits the proposed amendment to the states for their consideration, sending a letter of notification to each governor along with the informational material prepared by the OFR. The governors then formally submit the amendment to their state legislatures or call for a convention, as specified by Congress.

The second method, which has never been used, is for two-thirds of the state legislatures to request Congress to call a Constitutional Convention to propose amendments. This method was designed to balance between pliancy and rigidity, allowing for necessary changes while preventing impulsive reforms.

Once an amendment is ratified by three-fourths of the states (38 out of 50), it becomes part of the Constitution. The OFR verifies the receipt of authenticated ratification documents and drafts a formal proclamation for the Archivist to certify the amendment's validity. This certification is published in the Federal Register and U.S. Statutes at Large, serving as official notice to Congress and the nation that the amendment process is complete.

Amendments: The Constitution's Living Evolution

You may want to see also

Ratification by states

The process of amending the Constitution of the United States is outlined in Article V of the Constitution. Congress can propose an amendment with a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. The President does not have a constitutional role in the amendment process.

Once an amendment is proposed, it is submitted to the States for ratification. Three-fourths of the States (38 out of 50) must ratify the amendment for it to become part of the Constitution. This can be done through the state legislatures or through state-called conventions, depending on what Congress has specified.

In the past, some States have not waited for official notice before taking action on a proposed amendment. When a State ratifies, it sends an original or certified copy of the State action to the Archivist of the United States, who administers the ratification process. The Office of the Federal Register (OFR) examines ratification documents for legal sufficiency and an authenticating signature. If the documents are in order, the OFR acknowledges receipt and maintains custody until an amendment is adopted or fails, at which point the records are transferred to the National Archives for preservation.

The OFR verifies that it has received the required number of authenticated ratification documents before drafting a formal proclamation for the Archivist to certify that the amendment is valid and has become part of the Constitution. This certification is published in the Federal Register and U.S. Statutes at Large, serving as official notice to Congress and the Nation that the amendment process is complete.

It is worth noting that none of the 27 amendments to the Constitution have been proposed by a constitutional convention. All have been proposed by Congress, and the first ten amendments, known as the Bill of Rights, were ratified by three-fourths of the state legislatures on December 15, 1791.

The Challenge of Rescinding Constitutional Amendments

You may want to see also

The role of Congress

The United States Constitution grants Congress the authority to propose amendments. This power is derived from Article V of the Constitution, which outlines two methods for proposing amendments.

The first method, which has been used for all 33 amendments submitted to the states for ratification, requires a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. This method allows Congress to propose amendments directly, without the need for a convention. The joint resolution for the amendment is forwarded directly to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) for processing and publication, bypassing the President as they do not have a constitutional role in the amendment process.

The second method, which has never been used, is the convention option. This method requires Congress to call a convention for proposing amendments upon the request of two-thirds of the state legislatures. This option allows state legislatures to have a direct role in the amendment process, as they can apply for a convention on a specific issue or group of subjects. However, there are debates among scholars regarding Congress's control over other aspects of a convention, such as the rules of procedure and the vote threshold for proposing an amendment.

Once an amendment is proposed, either by Congress or through a convention, it must be ratified to become part of the Constitution. Ratification can occur through the legislatures of three-quarters of the states or by ratifying conventions in three-quarters of the states. The Archivist of the United States and the Director of the Federal Register play crucial roles in administering the ratification process, ensuring the amendment's validity and compliance with legal requirements.

Congress plays a central role in proposing and ratifying constitutional amendments. It can initiate the amendment process directly through a joint resolution or by calling for a convention upon the request of state legislatures. The specific procedures and requirements outlined in Article V ensure a balanced and deliberate approach to amending the nation's governing document.

The Unwritten Rights: Beyond the Constitution

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The President's role

The US Constitution does not outline a role for the President in amending the Constitution. The Supreme Court has also articulated the Judicial Branch's understanding that the President has no formal role in the process of amending the Constitution.

However, some Presidents have played a ministerial role in transmitting Congress's proposed amendments to the states for potential ratification. For example, President George Washington sent the first twelve proposed amendments, including the ten proposals that later became the Bill of Rights, to the states for ratification after Congress approved them. President Abraham Lincoln also signed the joint resolution proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish slavery, despite his signature not being necessary for the proposal or ratification of the amendment.

In recent history, the signing of the certification has become a ceremonial function attended by various dignitaries, including the President. President Johnson signed the certifications for the 24th and 25th Amendments, and President Nixon witnessed the certification of the 26th Amendment.

There have also been instances where Presidents have played a role in proposing amendments that would affect the Presidency. For example, the Twenty-second Amendment, which establishes term limits for the President, was ratified in 1951. It outlines that no person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice and no person who has held the office of President for more than two years of a term to which some other person was elected shall be elected to the office of President more than once.

Another example is Amendment Twelve, which was ratified on June 15, 1804, and outlines the procedure for how Presidents and Vice Presidents are elected, specifically so that they are elected together. It also mandates that a distinct vote must be taken for the President and the Vice President, and one of the selected candidates must be someone who is not from the same state as the elector.

The Power to Propose Constitutional Amendments

You may want to see also

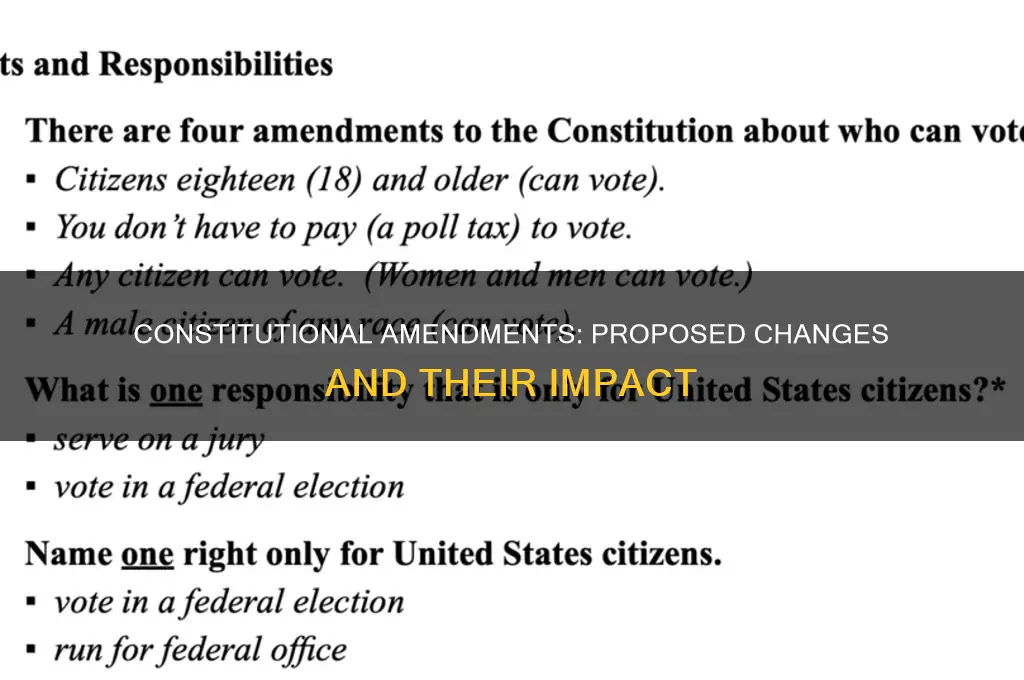

Rights-related amendments

The amendments James Madison proposed were designed to win support in both houses of Congress and the states. He focused on rights-related amendments, ignoring suggestions that would have structurally changed the government. Many Americans, persuaded by a pamphlet written by George Mason, opposed the new government. Mason was one of three delegates present on the final day of the convention who refused to sign the Constitution because it lacked a bill of rights. James Madison and other supporters of the Constitution argued that a bill of rights wasn't necessary because "the government can only exert the powers specified by the Constitution."

Madison, once the most vocal opponent of the Bill of Rights, introduced a list of amendments to the Constitution on June 8, 1789, and "hounded his colleagues relentlessly" to secure its passage. Madison had come to appreciate the importance voters attached to these protections, the role that enshrining them in the Constitution could have in educating people about their rights, and the chance that adding them might prevent its opponents from making more drastic changes. The House passed a joint resolution containing 17 amendments based on Madison's proposal. The Senate changed the joint resolution to consist of 12 amendments. A joint House and Senate Conference Committee settled remaining disagreements in September.

On October 2, 1789, President Washington sent copies of the 12 amendments adopted by Congress to the states. By December 15, 1791, three-fourths of the states had ratified 10 of these, now known as the "Bill of Rights." The first eight amendments of the Bill of Rights apply only to the federal government, not to the states or to private companies. The first ten amendments to the Constitution make up the Bill of Rights. James Madison wrote the amendments as a solution to limit government power and protect individual liberties through the Constitution.

The Ninth Amendment states that the "enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people." The Tenth Amendment has further been interpreted as a clarification of the federal government being largely limited and enumerated, and that a government decision is not to be investigated as a potential infringement of civil liberties, but rather as an overreach of its power and authority. Several Supreme Court decisions have invoked the Tenth Amendments, frequently when trying to determine if the federal government operated within, or overstepped, the bounds of its authority.

Lancaster House Constitution: Amendments Galore

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The U.S. Constitution outlines a two-step process for making amendments. First, an amendment must be proposed either by Congress with a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, or by a constitutional convention called for by two-thirds of state legislatures. Second, for an amendment to become part of the Constitution, it must be ratified by three-fourths of the states (38 of 50 states).

The President does not have a constitutional role in the amendment process.

The Archivist of the United States is responsible for administering the ratification process. The Archivist submits the proposed amendment to the states for their consideration and, once an amendment has been ratified by three-fourths of the states, the Archivist certifies that the amendment is valid and has become part of the Constitution.

Since the Constitution was put into operation in 1789, more than 11,000 amendments have been proposed, but only 27 have been ratified.

The first 10 amendments to the U.S. Constitution, known as the Bill of Rights, were ratified in 1791. They include:

- "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances."

- "A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed."

![The Constitution of Michigan as Proposed for Amendment 1874 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)