The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified in 1791, outlines several constitutional rights and limits the powers of the government in criminal procedures. It includes the Grand Jury Clause, which requires indictment by a grand jury before criminal charges for felonies, and the Due Process Clause, guaranteeing citizens a fair trial and protecting their life, liberty, and property. The amendment also provides the right against self-incrimination, protection against seizure of private property without compensation, and the Double Jeopardy Clause, prohibiting multiple trials for the same offense. These changes established fundamental rights and checks on governmental powers.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date of Ratification | December 15, 1791 |

| Rights Granted | Protection from self-incrimination, guaranteed due process and equal protection before the law, access to grand jury trials, and financial compensation in response to the government’s seizure of private property |

| Limits on | Federal government |

| Extent of Applicability | While the Fifth Amendment originally only applied to federal courts, the U.S. Supreme Court has partially incorporated the Fifth Amendment to the states through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment |

| Derived from | English common law, Magna Carta |

| Interpretation by Supreme Court | The Fifth Amendment protections against self-incrimination extend only to "natural persons". Corporations may be compelled to turn over records. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The Grand Jury Clause

The Fifth Amendment (Amendment V) to the United States Constitution, ratified in 1791, outlines several constitutional rights that limit governmental powers, particularly in criminal procedures. One of the key components of the Fifth Amendment is the Grand Jury Clause, which states that "no person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury". This clause ensures that individuals cannot be tried for serious crimes without first being indicted by a grand jury.

Grand juries typically consist of between 12 and 23 members, selected from a pool of prospective jurors. They have broad investigative authority and can consider evidence to determine whether there is probable cause to believe that a crime has been committed by a suspect. However, they are not allowed to conduct "fishing expeditions" or hire external individuals to locate testimony or documents.

The Supreme Court has ruled that the right to indictment by a grand jury does not apply to state-level crimes, only to federal felonies. This means that while most felonies at the federal level require indictment by a grand jury, this requirement does not extend to state-level criminal proceedings.

In summary, the Grand Jury Clause of the Fifth Amendment ensures that individuals cannot be tried for serious crimes without the prior approval of a grand jury. This clause is designed to protect the rights of the accused and prevent prosecutorial overreach. While it applies to federal crimes, it does not extend to all state-level criminal proceedings.

Arizona Constitution: Fourth Amendment Location

You may want to see also

The Due Process Clause

The Fifth Amendment's Due Process Clause, derived from the Magna Carta of 1215, states that no person shall be "deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law" by the federal government. This clause reflects a promise made by King John of England, in which he asserted that he would act only in accordance with the law and that all would receive the ordinary processes of the law.

The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, contains the same eleven words of the Due Process Clause, extending this obligation to the states. This means that all levels of American government must operate within the law and provide fair procedures. The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment has been used to incorporate most of the important elements of the Bill of Rights and make them applicable to the states.

Nevada Constitution: Amendments and Their Locations

You may want to see also

The Double Jeopardy Clause

The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution outlines several constitutional rights, limiting the powers of the government with respect to criminal procedures. The Double Jeopardy Clause, as part of the Fifth Amendment, provides the right of defendants to be tried only once for the same offence in federal court. The basic concept of the clause is that no person can be convicted twice for the same offence.

The effectiveness of the clause depends on whether two separate offences can be considered the same offence. For example, the charges of "conspiring to commit murder" and "murder" are typically considered distinct from each other, as they involve different facts. However, a person can be charged with "conspiring to commit murder" even if the murder never takes place, as long as all the necessary facts can be demonstrated through evidence.

- Jeopardy attaches in a jury trial when the jury is empaneled and sworn in.

- Jeopardy attaches in a bench trial when the court begins to hear evidence after the first witness is sworn in.

- Jeopardy attaches when a court accepts a defendant's plea unconditionally.

- Jeopardy does not attach in the retrial of a conviction that was reversed on appeal on procedural grounds (rather than evidentiary insufficiency grounds).

Amending Virginia's Constitution: A Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Self-incrimination

The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified in 1791, outlines several constitutional rights, including the right against self-incrimination. This right provides that no person can be compelled in a criminal case to be a witness against themselves. In other words, individuals have the right to remain silent and not provide self-incriminating testimony or evidence. This right applies in both federal and state courts.

The Self-Incrimination Clause of the Fifth Amendment has been the subject of numerous court interpretations and rulings over the years. In the landmark case of Miranda v. Arizona in 1966, the United States Supreme Court extended the protections of the Self-Incrimination Clause to any situation outside the courtroom that involves a curtailment of personal freedom. As a result, law enforcement must inform individuals in custody of their Miranda rights, which include the right to remain silent, the right to an attorney, and the right to a government-appointed attorney if they cannot afford one.

The Supreme Court has also clarified that the Fifth Amendment protections against self-incrimination apply only to "natural persons" and not to corporations. However, the Court has held that a corporation's custodian of records can be compelled to produce documents, even if doing so may incriminate them personally.

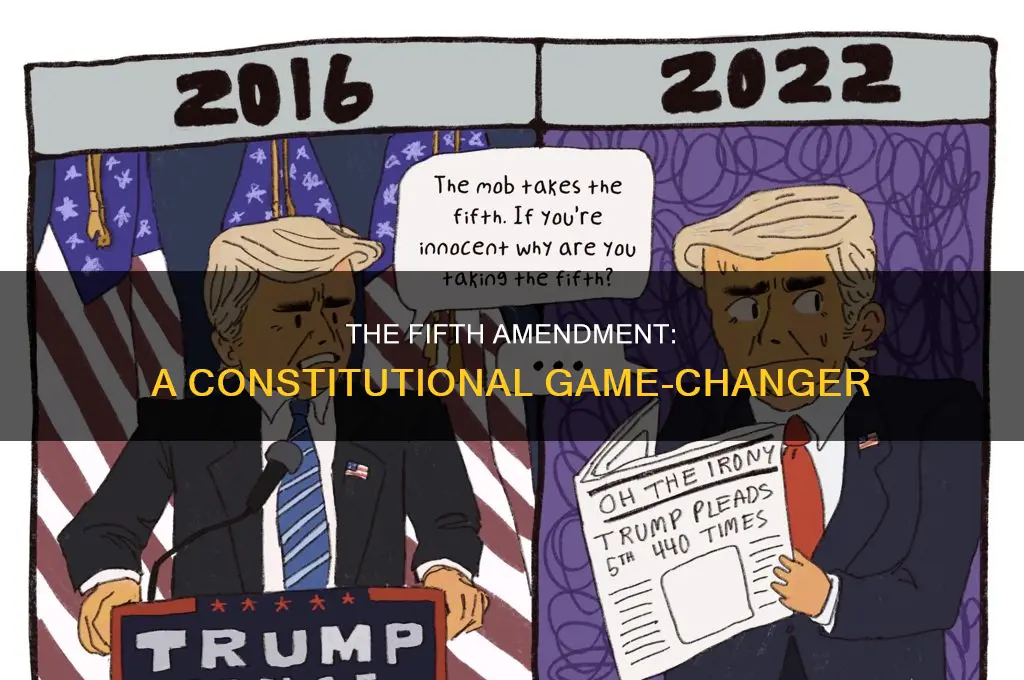

The Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination has been invoked in various criminal cases, including those involving the American Mafia. In the case of Salinas v. Texas, the Court affirmed that an individual must explicitly invoke their Fifth Amendment rights to be protected. This interpretation has been criticised by some Justices and legal scholars, who argue that it weakens the privilege against self-incrimination.

The Fifth Amendment's protection against self-incrimination has also been applied to situations beyond criminal proceedings. For example, in Haynes v. United States, the Supreme Court ruled that requiring felons to register their firearms constituted self-incrimination, as felons are prohibited from owning firearms. The lower courts have also grappled with the application of the Fifth Amendment in the digital age, with conflicting decisions on whether forced disclosure of computer passwords violates the right against self-incrimination.

Exploring Constitutional Amendments: Convention Required?

You may want to see also

Just Compensation Clause

The Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution outlines constitutional limits on police procedure and governmental powers, focusing on criminal procedures. The Just Compensation Clause, also known as the Takings Clause, is a part of the Fifth Amendment and states that "private property shall not be taken for public use without just compensation". This clause is derived from the Magna Carta, dating back to 1215.

The Just Compensation Clause protects citizens from having their private property confiscated by the government without receiving fair compensation. The Supreme Court has interpreted this clause to mean that the property owner shall receive at least the fair market value of the property, independent of the government taking. In most cases, this compensation is paid in cash, but it can also come in other forms, such as reciprocal benefits, like an increase in the value of retained land when the government builds a road over that property.

The clause also prohibits the government from confiscating property, even with just compensation, if it is not being used for a public purpose. This means that the government cannot take property from one private individual to give to another for their sole private benefit.

The Just Compensation Clause has been interpreted to apply to a range of situations, including when the government seizes personal property, such as in the case of Bennis v. Michigan, where the Court held that the government was not required to compensate an owner for property that it had already lawfully acquired through its authority. The clause has also been applied to cases involving trade secrets, as in Ruckelshaus v. Monsanto Co., where the Court distinguished between voluntary and involuntary exchanges of information.

The Takings Clause also addresses situations where the government requires property owners to take action to prevent harm to public or private property. In these cases, the government is not obligated to compensate owners for reasonable steps taken to avoid pollution or other harmful activities, as this falls under the government's authority to impose limitations for the public good.

Trump's Attempt to Rewrite the Constitution: What We Know

You may want to see also