Political polls are often seen as a reliable barometer of public opinion, yet their accuracy and impartiality are frequently called into question. The methodology, sample size, and framing of questions can introduce significant biases, skewing results in favor of particular candidates or ideologies. Additionally, factors like response rates, demographic representation, and the timing of surveys can further distort outcomes. Critics argue that polls are sometimes manipulated to influence voter behavior or media narratives, raising concerns about their credibility. As such, understanding the inherent limitations and potential biases of political polls is crucial for interpreting their findings and making informed decisions in an increasingly polarized political landscape.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Sampling Bias | Occurs when the sample of respondents does not accurately represent the population. For example, phone polls may underrepresent younger voters who are less likely to answer calls. |

| Response Bias | Arises when respondents provide inaccurate answers due to social desirability, reluctance to reveal true opinions, or misunderstanding questions. |

| Non-Response Bias | Happens when certain groups are less likely to participate in polls, skewing results. For instance, supporters of controversial candidates may be less willing to respond. |

| Question Wording | The phrasing of questions can influence responses. Leading or loaded questions can bias results toward a particular outcome. |

| Timing | Polls conducted closer to an election may capture temporary shifts in public opinion, while those conducted earlier may miss late-breaking trends. |

| Margin of Error | Polls typically report a margin of error (e.g., ±3%), but this can be higher for subgroups (e.g., specific demographics) due to smaller sample sizes. |

| Weighting | Pollsters adjust raw data to match demographic distributions (e.g., age, race, gender). Errors in weighting can introduce bias. |

| Party Affiliation | Respondents may misreport or shift their party affiliation, especially in polarized political climates. |

| Undecided Voters | Undecided or third-party voters can be difficult to predict and may break disproportionately for one candidate, affecting poll accuracy. |

| Online vs. Phone Polls | Online polls may overrepresent certain demographics (e.g., younger, more tech-savvy individuals), while phone polls may miss them. |

| Pollster Methodology | Different pollsters use varying methodologies, which can lead to discrepancies in results. |

| External Events | Unexpected events (e.g., scandals, debates) can shift public opinion rapidly, rendering earlier polls outdated. |

| Likely Voter Models | Pollsters use models to predict who will vote, but these models can be flawed, especially in high-turnout or unusual elections. |

| Geographic Bias | Polls may overrepresent urban or rural areas depending on sampling methods, affecting state-level predictions. |

| Historical Accuracy | While polls have generally been accurate in predicting election outcomes, notable failures (e.g., 2016 U.S. presidential election) highlight potential biases. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sampling Methods: How representative are poll samples of the population

- Question Wording: Does phrasing influence responses and skew results

- Timing of Polls: How do election proximity and events affect poll outcomes

- Response Bias: Do certain groups refuse polls, leading to skewed data

- Weighting Adjustments: How do pollsters correct data, and is it effective

Sampling Methods: How representative are poll samples of the population?

Political polls often claim to capture the pulse of the population, but their accuracy hinges on one critical factor: how representative their samples are. A sample that mirrors the demographic, geographic, and ideological diversity of the target population is essential for reliable results. However, achieving this balance is far from straightforward. Pollsters must navigate challenges like non-response bias, where certain groups (e.g., younger voters or those with strong political views) are more likely to participate, skewing the data. For instance, a poll relying solely on landline phone calls might underrepresent younger voters who primarily use mobile phones, potentially distorting the results in favor of older demographics.

Consider the practical steps involved in creating a representative sample. Stratified sampling, where the population is divided into subgroups (strata) based on factors like age, race, or region, ensures proportional representation. For example, if 20% of the population is aged 18–29, the sample should reflect this proportion. However, this method requires accurate census data and careful execution. Another approach is random sampling, which theoretically gives every individual an equal chance of being selected. Yet, even random samples can falter if the sampling frame (the list from which participants are drawn) is outdated or incomplete. For instance, voter registration lists might exclude eligible voters who haven’t registered, introducing bias.

The rise of online polling has introduced new complexities. While cost-effective and quick, online polls often rely on volunteers from panels or social media, leading to self-selection bias. Participants who opt-in tend to have stronger opinions or more free time, making them unrepresentative of the broader population. To mitigate this, pollsters use weighting techniques, adjusting the sample to match known population characteristics. However, weighting is not foolproof; it assumes the available demographic data is accurate and that attitudes correlate predictably with demographics, which isn’t always the case.

Comparing sampling methods reveals trade-offs. Probability-based methods, like random digit dialing, aim for statistical rigor but are expensive and time-consuming. Non-probability methods, such as convenience sampling (e.g., intercepting mall visitors), are cheaper but risk significant bias. For political polls, the stakes are high: a poorly representative sample can mislead campaigns, media, and voters. For example, the 2016 U.S. presidential election saw many polls underestimate support for Donald Trump, partly due to samples that underweighted rural and working-class voters.

To improve sample representativeness, pollsters should combine methods and leverage technology. For instance, blending phone, online, and in-person surveys can capture diverse populations. Additionally, using big data sources, like social media trends or consumer behavior, can supplement traditional sampling. However, transparency is key: pollsters must disclose their methods, sample sizes, and margins of error to allow for informed interpretation. Ultimately, while no sampling method is perfect, understanding their strengths and limitations is crucial for assessing the reliability of political polls.

Martin Scorsese's Political Views: Unveiling the Director's Ideological Stance

You may want to see also

Question Wording: Does phrasing influence responses and skew results?

The way a question is phrased in a political poll can significantly alter the responses received, often leading to skewed results. Consider the following example: a poll asking, "Do you support the government's efforts to increase taxes on the wealthy?" may yield different results compared to, "Do you think the wealthy should pay their fair share in taxes?" The former frames the issue as a government action, potentially triggering partisan reactions, while the latter appeals to a sense of fairness, which may resonate more broadly. This subtle difference in wording can shift public opinion, highlighting the power of language in shaping poll outcomes.

To illustrate the impact of question wording, let's examine a study by the Pew Research Center. They found that when asking about climate change, the term "global warming" elicited a 12% higher concern level than "climate change," despite both referring to the same phenomenon. This discrepancy arises from the connotations associated with each term: "global warming" implies an immediate, tangible threat, whereas "climate change" may seem more abstract and gradual. Pollsters must, therefore, carefully select terms to avoid inadvertently influencing respondents' views.

When designing polls, follow these steps to minimize bias from question wording: 1) Use clear, concise language to ensure respondents understand the question. 2) Avoid leading phrases that suggest a preferred answer. 3) Test questions on a small sample to identify potential biases. 4) Include a mix of open-ended and closed-ended questions to capture nuanced opinions. For instance, instead of asking, "Do you strongly agree or disagree with the new policy?" consider, "What are your thoughts on the recent policy changes?" This approach encourages respondents to express their views freely, reducing the risk of skewed results.

A comparative analysis of polls on healthcare reform reveals the extent to which wording can influence outcomes. A 2017 survey found that 54% of respondents supported "Obamacare," while only 37% backed the "Affordable Care Act," even though both refer to the same legislation. This disparity stems from the political polarization surrounding the term "Obamacare." Pollsters should be aware of such associations and strive to use neutral language to obtain accurate results. By doing so, they can provide a more reliable snapshot of public opinion.

In conclusion, question wording plays a pivotal role in shaping poll responses, often leading to biased or skewed results. To mitigate this, pollsters must employ careful language selection, avoid leading phrases, and test questions rigorously. By adopting these practices, they can enhance the accuracy and reliability of political polls, ultimately providing a more truthful representation of public sentiment. As consumers of poll data, it's essential to critically evaluate question wording to discern potential biases and interpret results accordingly.

Is Politico Available in Print? Exploring Subscription Options

You may want to see also

Timing of Polls: How do election proximity and events affect poll outcomes?

The timing of political polls is a critical factor that can significantly skew results, often leading to misinterpretations of public sentiment. As elections approach, polls tend to tighten, reflecting the increased engagement of undecided voters and the intensification of campaign efforts. For instance, a poll conducted six months before an election might show a double-digit lead for one candidate, but that gap often narrows to within the margin of error in the final weeks. This phenomenon is not merely coincidental; it stems from the heightened media coverage, debates, and advertising that occur as Election Day looms, all of which can sway voter opinions.

Consider the role of events in this dynamic. A high-profile scandal, a successful debate performance, or an unexpected endorsement can dramatically shift poll numbers overnight. For example, during the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, the release of the "Access Hollywood" tape caused a temporary dip in Donald Trump’s polling numbers, while Hillary Clinton’s numbers surged. However, by the time of the election, the impact had largely dissipated. This illustrates how the timing of such events relative to the election can determine their lasting effect on poll outcomes. Pollsters must account for these fluctuations, often weighting responses based on recency to capture the most current sentiment.

To mitigate timing-related biases, pollsters employ specific strategies. One common approach is to conduct rolling polls, which survey a small sample of respondents daily and aggregate the results over a week. This method smooths out short-term volatility caused by events and provides a more stable snapshot of public opinion. Another strategy is to focus on likely voters rather than registered voters as the election nears, as this group is more predictive of actual turnout. For instance, a poll targeting likely voters in the final week of a campaign might exclude individuals who have not voted in recent elections, thereby reducing noise in the data.

However, even these strategies have limitations. Events that occur in the final days before an election, such as a natural disaster or a last-minute revelation about a candidate, can still skew results. In the 2012 U.S. presidential election, Hurricane Sandy hit the East Coast just before Election Day, potentially influencing voter turnout and preferences. Pollsters had little time to adjust their models, leading to discrepancies between predictions and actual outcomes. This highlights the inherent challenge of timing: no matter how sophisticated the methodology, unforeseen events can always introduce bias.

Practical takeaways for interpreting polls include examining the fieldwork dates and the sample composition. Polls conducted immediately after a major event may overstate its impact, while those taken weeks before an election may underestimate the influence of late-breaking developments. Additionally, comparing polls from different time periods requires caution, as shifts in methodology or voter engagement can confound the analysis. By understanding how timing interacts with events and polling techniques, readers can better discern the reliability of poll results and avoid being misled by transient trends.

Is All Punk Political? Exploring the Genre's Radical Roots and Impact

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Response Bias: Do certain groups refuse polls, leading to skewed data?

Political polls rely on participation, but not everyone answers the phone or clicks through an online survey. This non-response can skew results if those who decline differ significantly from those who participate. Imagine a poll about tax policy where high-income earners, often busier and more guarded about their time, are less likely to respond. The results might overrepresent the views of lower-income groups, painting an incomplete picture of public opinion.

This phenomenon, known as response bias, is a silent saboteur of polling accuracy.

Consider the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Many polls predicted a Hillary Clinton victory, but Donald Trump emerged victorious. Post-election analyses pointed to response bias as a contributing factor. Trump supporters, often disillusioned with the political establishment, were less likely to engage with pollsters. This underrepresentation of their views led to a miscalculation of the true electoral landscape.

Similarly, younger voters, who tend to be more mobile and less tied to landlines, are frequently missed in traditional phone polls. Their opinions, often leaning progressive, can be underrepresented, skewing results towards more conservative viewpoints.

Identifying response bias is crucial, but mitigating it is challenging. Pollsters employ various strategies, such as offering incentives for participation or using multiple contact methods (phone, email, online panels). However, these methods aren't foolproof. Incentives might attract respondents who are more motivated by rewards than by genuine interest in the topic, while multi-method approaches can be costly and time-consuming.

To navigate the murky waters of response bias, consumers of political polls must be critical thinkers. Look beyond the headline numbers. Examine the poll's methodology: How were respondents contacted? What was the response rate? Were demographic weights applied to adjust for underrepresentation? Understanding these details allows for a more nuanced interpretation of the data and a healthier skepticism towards polling results.

Navigating Identity Politics: Strategies for Inclusive and Empowering Education

You may want to see also

Weighting Adjustments: How do pollsters correct data, and is it effective?

Political polls often face criticism for bias, but one of the primary tools pollsters use to correct for inaccuracies is weighting adjustments. This process involves recalibrating raw survey data to match known demographic characteristics of the population being studied, such as age, gender, race, education, and geographic location. For example, if a poll oversamples college-educated respondents, weighting adjustments reduce their influence to reflect the actual proportion of college graduates in the population. Without this step, polls risk overrepresenting certain groups, skewing results in favor of their preferences or beliefs.

The mechanics of weighting adjustments are both precise and complex. Pollsters start by comparing their sample to benchmark data from reliable sources like the U.S. Census. If 25% of the population is aged 18–29 but only 15% of the survey respondents fall into this category, the pollster applies a higher weight to the responses of younger participants. This ensures their opinions carry more influence in the final results. However, this method is not without challenges. Overweighting can amplify errors if the benchmark data is outdated or if the sample contains hidden biases not accounted for in the weighting scheme.

Despite its technical rigor, the effectiveness of weighting adjustments depends heavily on the quality of the underlying data. For instance, during the 2016 U.S. presidential election, many polls underestimated support for Donald Trump because they failed to adequately weight for education levels, particularly among white voters without college degrees. This oversight led to samples that overrepresented college-educated voters, who were more likely to support Hillary Clinton. While weighting can correct for known demographics, it cannot account for unknown or unmeasured factors, such as voter enthusiasm or turnout likelihood, which can significantly impact outcomes.

Critics argue that weighting adjustments are a band-aid solution, masking deeper issues in survey methodology. For example, relying on census data assumes that demographic distributions remain static, which is often not the case in rapidly changing populations. Additionally, weighting can introduce its own biases if the benchmarks are flawed or if pollsters make arbitrary decisions about which variables to prioritize. To mitigate these risks, some pollsters use iterative weighting, a more sophisticated approach that adjusts multiple variables simultaneously, ensuring a more balanced representation.

In practice, weighting adjustments are a necessary but imperfect tool in the pollster’s arsenal. When applied thoughtfully, they can significantly improve the accuracy of political polls by aligning samples with real-world demographics. However, their effectiveness hinges on careful execution and an awareness of their limitations. Poll consumers should scrutinize not just the results but also the methodology, asking how and why certain weights were applied. In an era of increasing polarization and demographic shifts, the art of weighting remains a critical—yet contentious—aspect of polling science.

Is All Poetry Political? Exploring Verse, Voice, and Power Dynamics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

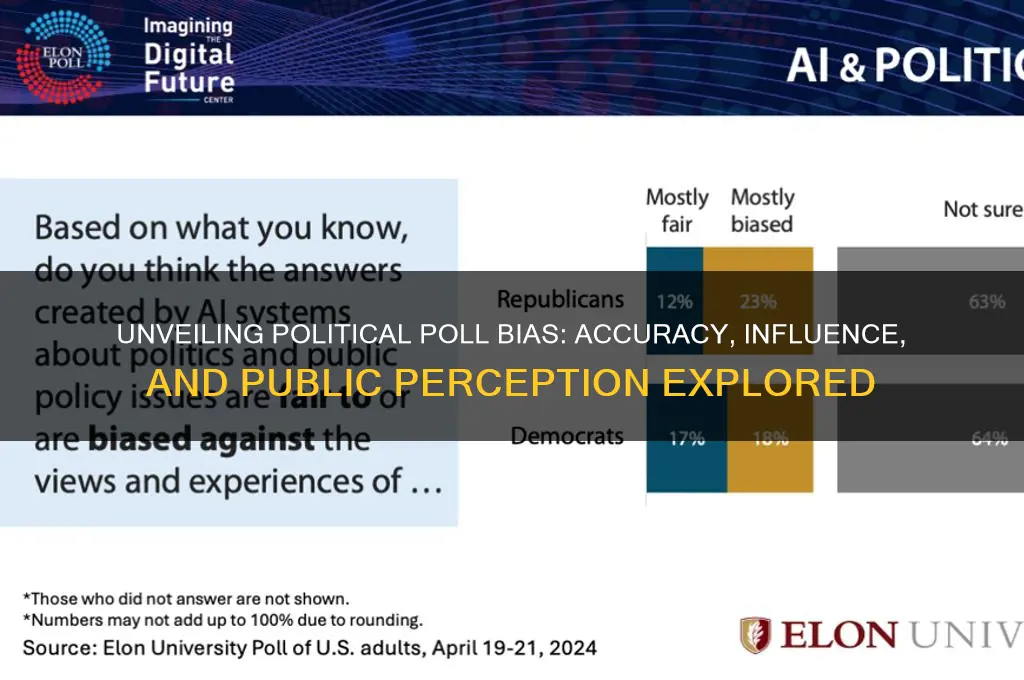

Political polls are not inherently biased, but they can be influenced by factors like question wording, sample selection, and timing. Bias often arises from methodological flaws or intentional manipulation rather than the polling process itself.

While reputable pollsters adhere to ethical standards, some organizations may skew results through biased questions, weighted samples, or selective reporting. Always check the poll’s methodology and source for credibility.

Yes, polls can overrepresent or underrepresent demographics like age, race, or political affiliation if the sample isn’t properly weighted to reflect the population. This can lead to skewed results, especially in polarized elections.

Polls may differ due to variations in timing, sample size, methodology, or population surveyed. Additionally, small differences in wording or context can yield divergent results, making it important to compare polls critically.