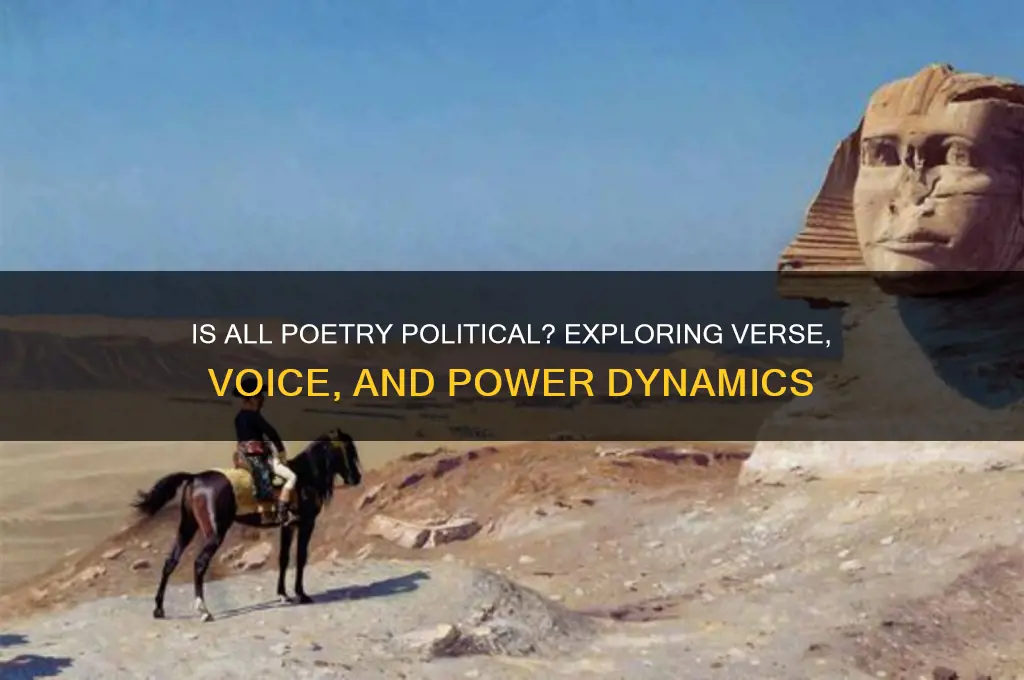

The question of whether all poetry is inherently political has long sparked debate among writers, scholars, and readers. At its core, poetry often reflects the human experience, which is deeply intertwined with societal structures, power dynamics, and cultural contexts. Even when a poem does not explicitly address political issues, its themes, language, and perspective can subtly challenge or reinforce prevailing norms, making it a form of expression that inherently engages with the world around it. From the revolutionary verses of Pablo Neruda to the personal yet socially charged works of Audre Lorde, poetry has historically served as both a mirror and a tool for critique, blurring the lines between the personal and the political. Thus, while not all poetry may wear its politics on its sleeve, its very existence within a social framework invites consideration of its role in shaping or resisting the status quo.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Subject Matter | Poetry often reflects societal issues, personal experiences, and cultural contexts, which inherently carry political undertones. |

| Voice and Perspective | Poets use their work to express opinions, challenge norms, or advocate for change, making their voice a political tool. |

| Historical Context | Poetry has historically been used to document resistance, revolution, and social movements, highlighting its political nature. |

| Intent and Impact | While not all poets intend to create political statements, their work can still influence political discourse and awareness. |

| Ambiguity and Interpretation | Poetry's open-ended nature allows readers to interpret political messages, even if the poet did not explicitly intend them. |

| Form and Style | Experimental forms and styles can challenge traditional power structures, making the structure itself a political act. |

| Censorship and Suppression | Poetry that critiques authority or dominant ideologies often faces censorship, underscoring its political potential. |

| Personal as Political | Even seemingly personal poems can be political when they address identity, marginalization, or systemic issues. |

| Global and Local Perspectives | Poetry can engage with both local and global political issues, bridging personal and universal concerns. |

| Artistic Freedom | The act of creating poetry itself can be a political statement, asserting freedom of expression in repressive environments. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Art vs. Activism: Can poetry exist purely for aesthetics, or does it inherently carry political weight

- Voice of the Marginalized: How does poetry amplify silenced voices and challenge power structures

- Historical Context: Does the political climate of an era shape poetic themes and forms

- Personal as Political: Are intimate, individual experiences in poetry inherently tied to broader societal issues

- Censorship and Poetry: How do political regimes control or suppress poetic expression

Art vs. Activism: Can poetry exist purely for aesthetics, or does it inherently carry political weight?

Poetry, at its core, is a form of expression that distills human experience into language. Yet, the question persists: can it ever be apolitical? Consider the act of choosing words, rhythms, and imagery—each decision reflects a perspective shaped by societal norms, personal biases, and cultural contexts. Even a poem about a solitary flower in a field implicitly engages with the world around it, whether by celebrating nature’s beauty or ignoring its fragility in the face of environmental degradation. This suggests that poetry, by its very nature, cannot escape the gravitational pull of politics, even when it appears to focus solely on aesthetics.

To explore this further, examine the historical role of poetry in activism. From Langston Hughes’s *Montage of a Dream Deferred* to Maya Angelou’s *Still I Rise*, poets have long used verse to challenge power structures and amplify marginalized voices. These works are undeniably political, but they are also celebrated for their artistic merit. This duality raises a critical point: poetry’s political weight often enhances its aesthetic value, as it resonates deeply with readers who recognize their own struggles or aspirations reflected in the words. Thus, the line between art and activism blurs, suggesting that even the most politically charged poetry can be judged on its artistic craftsmanship.

However, not all poetry explicitly addresses political themes. Haiku, for instance, often focuses on fleeting moments in nature, stripped of overt political commentary. Yet, even here, the poet’s choice to highlight a particular scene—a falling leaf, a chirping bird—can be seen as a statement about the importance of mindfulness or the transience of life. This subtlety does not render the poem apolitical but rather embeds its politics in a quieter, more contemplative form. The takeaway? Poetry’s political weight can be implicit, woven into its aesthetic fabric rather than shouted from the rooftops.

For those seeking to create or analyze poetry, consider this practical approach: dissect a poem’s language, form, and imagery to uncover its underlying assumptions. Ask: Whose voices are centered? What perspectives are excluded? How does the poem interact with broader societal issues? For example, a love poem might appear apolitical, but if it reinforces heteronormative ideals, it subtly upholds a particular political worldview. By adopting this lens, readers and writers alike can engage with poetry as both an art form and a tool for critical inquiry.

Ultimately, the debate between art and activism in poetry is not a binary choice but a spectrum. While some poems may prioritize aesthetic beauty, their creation and reception are inevitably shaped by the political and social contexts in which they exist. To dismiss poetry’s inherent political weight is to overlook its power to reflect, challenge, and transform the world. Conversely, to reduce poetry to mere activism risks stripping it of its artistic complexity. The most enduring poems often achieve a delicate balance, proving that aesthetics and politics are not adversaries but intertwined elements of the human experience.

Mastering the Art of Polite Rescheduling: Tips for Graceful Communication

You may want to see also

Voice of the Marginalized: How does poetry amplify silenced voices and challenge power structures?

Poetry has long served as a megaphone for the marginalized, transforming whispers of dissent into roars that echo across societies. Consider the works of Audre Lorde, whose poems like "Coal" and "Sister Outsider" not only articulate the experiences of Black, queer women but also dismantle the intersectional oppressions they face. Her lines are not mere expressions of pain; they are strategic acts of resistance, using vivid imagery and unapologetic tone to force readers to confront uncomfortable truths. This is poetry as a weapon—sharp, precise, and unyielding in its challenge to dominant narratives.

To amplify silenced voices effectively, poets must employ specific techniques that transcend passive observation. For instance, the use of dialect or vernacular, as seen in Langston Hughes’ *Montage of a Dream Deferred*, grounds the poem in the lived realities of its subjects. Similarly, the repetition of phrases or the fragmentation of syntax can mimic the disjointedness of oppression, as in the works of Mahmoud Darwish, whose poetry about Palestinian displacement refuses to let the world forget. Practical tip: When crafting such poetry, avoid abstraction; anchor your words in tangible details—a cracked sidewalk, a faded photograph, a specific accent—to make the invisible undeniable.

However, amplifying marginalized voices through poetry is not without risks. Poets often face backlash, censorship, or even physical danger. Take the case of Kenyan poet and activist Njeri Wangari, whose works critique state violence and patriarchy, leading to threats against her life. Caution: If you are writing politically charged poetry, consider pseudonyms, encrypted platforms, or collaborative publishing to protect yourself. Additionally, ally poets must tread carefully; amplification should never overshadow the voices they aim to support. Instead, use your privilege to create spaces—readings, anthologies, workshops—where marginalized poets can speak for themselves.

Comparatively, poetry’s ability to challenge power structures lies in its dual nature: it is both intimate and universal. While a poem like June Jordan’s "I Am a Black Woman" speaks directly to the experiences of Black women, its themes of resilience and defiance resonate across cultures and histories. This duality allows poetry to infiltrate even the most fortified power structures, bypassing intellectual defenses to strike at emotional and moral cores. For maximum impact, pair personal narratives with broader systemic critiques, as in the works of Rupi Kaur, whose simplicity belies a profound dismantling of societal norms.

Ultimately, poetry’s role in amplifying silenced voices is not just artistic—it is transformative. By giving language to the unspeakable, poets create a shared vocabulary for resistance, turning individual struggles into collective movements. Takeaway: Whether you are a marginalized poet or an ally, remember that every line you write or share is a step toward rewriting the power dynamics of the world. Start small: attend open mics, submit to inclusive journals, or teach poetry in underserved communities. In the words of Adrienne Rich, “Poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity.” Use it as such.

Stream Polite Society: A Step-by-Step Guide to Watching the Film

You may want to see also

Historical Context: Does the political climate of an era shape poetic themes and forms?

Poetry, often seen as a mirror to society, has historically been intertwined with the political climate of its era. The tumultuous years of the 20th century, for instance, birthed movements like the Beat Generation in the 1950s, which rebelled against conformity and materialism in post-war America. Allen Ginsberg’s *Howl* became a manifesto against political oppression and social alienation, illustrating how poets respond to the pressures of their time. This example underscores that political climates not only influence poetic themes but also catalyze new forms of expression, often as acts of resistance or reflection.

To understand this dynamic, consider the role of censorship and patronage in shaping poetry. During the Renaissance, poets like Edmund Spenser and William Shakespeare navigated the political expectations of their patrons, often embedding allegorical critiques within their works. In contrast, the Soviet Union’s Iron Curtain era saw poets like Anna Akhmatova using cryptic language to evade state censorship while still addressing themes of suffering and resistance. These historical instances demonstrate that political climates can both constrain and inspire poetic innovation, forcing writers to adapt their forms and themes to survive or subvert authority.

A comparative analysis of war poetry across eras further highlights this relationship. World War I poets like Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon used stark, visceral imagery to expose the horrors of trench warfare, directly challenging the romanticized narratives of war propagated by political leaders. In contrast, the Vietnam War era saw poets like Yusef Komunyakaa blending personal and political narratives, reflecting the anti-war sentiment and racial tensions of the 1960s. These examples reveal how the political urgency of an era dictates not only the content but also the tone and structure of poetry, often shifting from formal to free verse as societal norms evolve.

Practical observation of this phenomenon requires examining how poets engage with contemporary issues. For instance, the Black Lives Matter movement has inspired a resurgence of protest poetry, with poets like Amanda Gorman using their platforms to address systemic racism and inequality. Workshops and anthologies focused on politically charged themes have become common, offering poets tools to craft impactful work. Aspiring writers can study these trends by analyzing how historical events—such as civil rights movements or economic crises—have shaped poetic movements, then applying those lessons to current issues.

In conclusion, the political climate of an era undeniably shapes poetic themes and forms, often pushing poets to innovate in response to societal pressures. By studying historical examples and engaging with contemporary issues, writers can harness this dynamic to create poetry that resonates both artistically and politically. Whether through allegory, protest, or personal reflection, poetry remains a powerful medium for capturing the spirit of its time.

Mastering the Art of Trolling Political Texts: Tips and Tricks

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Personal as Political: Are intimate, individual experiences in poetry inherently tied to broader societal issues?

Poetry often begins with the personal, but its resonance frequently extends far beyond the individual. A poem about a mother’s grief, for instance, may start as a deeply private expression of loss. Yet, when it articulates the universal experience of mourning, it inadvertently connects to broader societal issues—how cultures process grief, the role of women as caregivers, or the inadequacy of public support systems for the bereaved. This transformation of the personal into the political is not always intentional but is nearly inevitable, as language itself carries the weight of shared human experience.

Consider the act of writing about mental health struggles. A poet detailing their battle with anxiety or depression might focus on internal sensations—the tightening chest, the spiraling thoughts. However, such a poem inherently critiques a society that stigmatizes mental illness, prioritizes productivity over well-being, or underfunds healthcare. The personal narrative becomes a political statement by virtue of its existence, challenging dominant narratives and demanding recognition for marginalized experiences. This duality is not a flaw but a strength, as it allows poetry to function both as a mirror to the self and a window to the world.

To explore this dynamic, examine the work of poets like Audre Lorde or Ocean Vuong. Lorde’s *“Coal”* intertwines her identity as a Black lesbian woman with critiques of systemic oppression, proving that the body and its experiences are inherently political. Vuong’s *“Night Sky with Exit Wounds”* uses intimate reflections on love and loss to address themes of immigration, queerness, and war. These poets demonstrate that even when the focus is personal, the act of writing and sharing such experiences disrupts silence and challenges power structures. Practical tip: When analyzing poetry, ask not only *what* is being said but *what systems* are being questioned or reinforced through the act of saying it.

However, caution is necessary. Not all personal poetry seeks or achieves political impact. A poem about a first kiss, for instance, might remain purely sentimental, devoid of broader implications. The key lies in the poet’s intent and the reader’s interpretation. A poem’s political potential is often realized in its reception—how readers connect its themes to their own lives or societal contexts. For educators or writers, encouraging this connection can deepen engagement. Exercise: Pair a personal poem with a news article or historical text that reflects its themes, prompting readers to draw parallels between the intimate and the collective.

Ultimately, the personal-political link in poetry is not a binary but a spectrum. While not all intimate experiences inherently carry political weight, their expression in poetry often amplifies them into statements about the human condition. This is because poetry, at its core, is an act of communication—and communication, even in its most private forms, occurs within a social framework. By embracing this duality, poets and readers alike can harness the power of the personal to illuminate and challenge the world at large.

Mastering the Art of Polite RSVP: Etiquette Tips for Every Occasion

You may want to see also

Censorship and Poetry: How do political regimes control or suppress poetic expression?

Poetic expression has long been a thorn in the side of authoritarian regimes, its ambiguity and emotional resonance making it a powerful tool for dissent. To neutralize this threat, regimes employ a multi-pronged approach to censorship, targeting poets, their work, and the very act of poetic creation.

Direct Suppression: The most blatant form of censorship involves outright bans on specific poems, poets, or entire genres deemed subversive. This can include book burnings, arrests, and even executions. For instance, during Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution in China, poets like Ai Qing were persecuted and their works destroyed for deviating from the approved socialist realist style.

Institutional Control: Regimes often exert control through state-sanctioned publishing houses, literary academies, and educational curricula. By controlling the means of production and dissemination, they can dictate what poetry is deemed "acceptable" and worthy of publication or study. This creates a chilling effect, discouraging poets from venturing beyond approved themes and styles.

Self-Censorship: Perhaps the most insidious form of censorship is self-censorship, where poets internalize the regime's values and limitations, preemptively tailoring their work to avoid repercussions. This subtle erosion of artistic freedom can be even more effective than direct suppression, as it stifles creativity at its source.

Subversion Through Ambiguity: Poets, however, are adept at subverting censorship through the very nature of their craft. The inherent ambiguity of poetry allows for layered meanings and hidden critiques. Metaphors, symbolism, and allegory become weapons against oppression, allowing poets to express dissent while maintaining plausible deniability. Pablo Neruda's poetry, for example, often employed oblique references to criticize the Chilean dictatorship, its true meaning accessible only to those attuned to the political context.

Resilience and Resistance: Despite the efforts of censors, poetry persists as a powerful tool for resistance. Underground networks, samizdat publications, and oral traditions ensure that suppressed voices continue to be heard. The very act of writing and sharing poetry under oppressive regimes becomes an act of defiance, a testament to the human spirit's yearning for freedom and expression.

Dada Art's Political Rebellion: Challenging Authority Through Absurdity and Provocation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Not necessarily. While poetry can address political themes, it can also explore personal, emotional, or aesthetic subjects without direct political intent.

Yes, poetry can be political through its themes, tone, or subtext, even if it doesn't directly reference political events or figures.

Poetry has historically been used to challenge authority, express dissent, and amplify marginalized voices, making it a powerful tool for political expression.

Not always. Personal experiences can intersect with broader social or political issues, making even intimate poetry politically relevant.

Yes, poetry can focus on themes like nature, love, or abstract ideas without engaging with political discourse, though some argue all art exists within a political context.