The question of whether political Islam has failed is a complex and contentious issue that has sparked intense debates among scholars, policymakers, and the public alike. Emerging as a significant force in the late 20th century, political Islam sought to establish Islamic principles as the foundation of governance, often in response to perceived Western influence and secular authoritarianism. However, its trajectory has been marked by both successes and setbacks, with varying degrees of implementation and outcomes across different regions. Critics argue that political Islam has struggled to reconcile religious doctrine with modern democratic values, leading to authoritarian tendencies, economic stagnation, and social divisions in some cases. Proponents, on the other hand, contend that its failures are often exaggerated and that it remains a legitimate expression of Muslim identity and aspirations. As the global political landscape continues to evolve, the debate over the efficacy and future of political Islam remains a crucial aspect of understanding contemporary Middle Eastern and global politics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Decline in Electoral Support | Decreased voter turnout for Islamist parties in recent elections (e.g., Ennahda in Tunisia, AKP in Turkey). |

| Economic Challenges | Failure to address economic inequalities, high unemployment, and inflation in Islamist-led governments. |

| Internal Divisions | Splits within Islamist movements (e.g., Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, Jamaat-e-Islami in Pakistan). |

| Secular Backlash | Rise of secular and liberal movements opposing Islamist policies (e.g., protests in Iran, Turkey). |

| Authoritarian Tendencies | Accusations of authoritarianism and suppression of dissent in Islamist regimes (e.g., Sudan, Iran). |

| Failure to Modernize | Inability to reconcile traditional Islamic principles with modern governance and global norms. |

| Regional Instability | Islamist movements contributing to or failing to resolve conflicts (e.g., Syria, Libya, Somalia). |

| Loss of Youth Support | Younger generations increasingly rejecting political Islam in favor of secular or progressive ideologies. |

| Global Perception | Negative international perception due to associations with extremism and terrorism. |

| Policy Inconsistencies | Inconsistent implementation of Islamic law and failure to deliver on promises of moral governance. |

| Rise of Alternative Movements | Emergence of non-Islamist political movements gaining popularity (e.g., nationalist parties in Turkey, reformists in Iran). |

| Cultural Shifts | Growing cultural liberalization in traditionally Islamist societies (e.g., women's rights movements in Saudi Arabia). |

| External Interventions | Foreign interventions undermining Islamist governments (e.g., Egypt, Afghanistan). |

| Religious Apathy | Increasing religious apathy or secularization among populations in Muslim-majority countries. |

| Lack of Unified Vision | Fragmentation of Islamist ideologies and lack of a cohesive global strategy. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Decline of Islamist movements in the Middle East and North Africa

- Failure to establish sustainable Islamic governance models globally

- Internal divisions weakening political Islam's unified front

- Public disillusionment with Islamist parties in democratic elections

- Secularization trends reducing political Islam's societal influence

Decline of Islamist movements in the Middle East and North Africa

The Arab Spring, which began in 2010, marked a turning point for Islamist movements in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Initially, these movements gained traction, with the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and Ennahda in Tunisia ascending to power through democratic elections. However, their brief tenures revealed significant challenges. In Egypt, the Brotherhood’s inability to address economic crises and its polarizing governance style led to widespread discontent, culminating in a military coup in 2013. Tunisia’s Ennahda, though more pragmatic, faced similar pressures, stepping down in 2014 amid political instability and public disillusionment. These cases illustrate how Islamist parties struggled to translate religious ideology into effective governance, alienating both secular and religious constituencies.

Analyzing the decline of Islamist movements requires examining their internal contradictions and external pressures. Internally, many Islamist groups failed to modernize their agendas, clinging to rigid interpretations of Sharia law that alienated younger, more liberal populations. Externally, regional powers like Saudi Arabia and the UAE actively opposed Islamist movements, viewing them as threats to their authoritarian regimes. This dual pressure eroded their support base, as they were unable to deliver on promises of economic prosperity or political stability. For instance, in Libya, Islamist factions became entangled in civil war, further discrediting their ability to govern.

A comparative look at Morocco offers a nuanced perspective. The Justice and Development Party (PJD), an Islamist party, has maintained a presence in government since 2011, albeit with limited power. Morocco’s monarchy, unlike other MENA regimes, co-opted rather than suppressed Islamists, allowing them a controlled role in governance. This strategy highlights a critical takeaway: Islamist movements’ decline is not universal but contingent on political contexts. Where authoritarian regimes dominate, Islamists face suppression; where institutions are more inclusive, they may survive, albeit in diminished form.

To understand the practical implications of this decline, consider the rise of non-ideological movements in the region. Youth-led protests in Sudan, Algeria, and Lebanon have focused on corruption, economic reform, and political freedom, sidelining religious rhetoric. This shift suggests that the next generation prioritizes tangible outcomes over ideological purity. For activists and policymakers, this trend underscores the need to address root causes of discontent—economic inequality, corruption, and lack of opportunity—rather than focusing solely on ideological battles.

In conclusion, the decline of Islamist movements in MENA is a complex phenomenon shaped by governance failures, regional geopolitics, and shifting societal priorities. While not entirely defunct, these movements have lost their once-dominant appeal. Their future hinges on their ability to adapt to modern challenges and engage with younger, more pragmatic populations. For observers and stakeholders, the lesson is clear: the failure of political Islam is not a defeat of religion but a call for more inclusive, effective governance models.

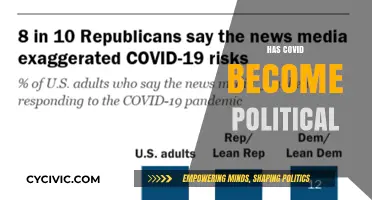

COVID-19: Political Maneuver or Global Health Crisis?

You may want to see also

Failure to establish sustainable Islamic governance models globally

The quest to establish sustainable Islamic governance models globally has faced significant challenges, with many attempts faltering under the weight of internal contradictions, external pressures, and practical implementation failures. Despite the ideological fervor that often accompanies such projects, the reality on the ground tells a story of unmet expectations and systemic vulnerabilities. For instance, the Islamic Republic of Iran, established in 1979, has struggled to balance religious orthodoxy with modern governance demands, leading to economic stagnation, political repression, and international isolation. This case highlights a recurring theme: the tension between ideological purity and pragmatic governance often undermines the long-term viability of Islamic political systems.

Consider the steps required to build a sustainable Islamic governance model. First, there must be a clear, universally accepted framework for Islamic law (Sharia) that can adapt to contemporary issues without compromising its core principles. Second, institutions must be designed to ensure transparency, accountability, and inclusivity, addressing the historical tendency toward authoritarianism in many Islamic political experiments. Third, economic policies must prioritize development, innovation, and social welfare, rather than relying on resource extraction or external aid. However, these steps are rarely fully realized. For example, in Afghanistan under the Taliban, rigid interpretations of Sharia and a lack of administrative expertise led to widespread human rights abuses and economic collapse, demonstrating the pitfalls of prioritizing ideology over governance capacity.

A comparative analysis reveals that the failure of Islamic governance models is not inherent to the ideology itself but often stems from poor execution and external interference. Countries like Malaysia and Indonesia have managed to integrate Islamic principles into democratic frameworks, achieving relative stability and economic growth. However, these successes are exceptions rather than the rule. In contrast, states like Sudan and Somalia have seen Islamic political projects devolve into civil war and state failure, underscoring the importance of context-specific strategies and strong institutional foundations. The takeaway is clear: without a nuanced approach that balances religious ideals with practical governance, even the most well-intentioned Islamic political projects are doomed to fail.

To address these challenges, proponents of Islamic governance must adopt a pragmatic, incremental approach. This involves piloting policies in localized contexts, such as Islamic finance or education reforms, before scaling them nationally. It also requires engaging with global norms on human rights and democracy, rather than viewing them as antithetical to Islamic values. For instance, Morocco’s 2011 constitutional reforms, which incorporated Sharia while strengthening democratic institutions, offer a model for gradual integration. Practical tips include investing in education to foster a new generation of leaders capable of navigating the complexities of modern governance and leveraging technology to enhance transparency and citizen participation.

Ultimately, the failure to establish sustainable Islamic governance models globally is a call to rethink strategies rather than abandon the endeavor entirely. By learning from past mistakes, embracing adaptability, and prioritizing good governance over ideological rigidity, there remains potential for Islamic political systems to thrive. The challenge lies not in the principles of Islam but in their application—a lesson that must guide future efforts if they are to succeed where others have faltered.

Does AARP Engage in Political Advocacy? Uncovering Their Stance and Influence

You may want to see also

Internal divisions weakening political Islam's unified front

Political Islam, as a unified ideological force, has been significantly undermined by internal fractures that erode its coherence and effectiveness. One of the most glaring examples is the schism between Sunni and Shia factions, which has historically divided Muslim-majority nations and continues to fuel conflicts in regions like the Middle East. This sectarian divide is not merely theological but has profound political implications, as seen in the proxy wars between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Such divisions dilute the collective strength of political Islam, making it difficult to present a unified front against external challenges or to implement a cohesive vision for governance.

Another layer of internal division arises from the ideological clashes between Islamist groups themselves. For instance, the Muslim Brotherhood’s emphasis on gradual political reform contrasts sharply with the militant strategies of groups like Al-Qaeda or ISIS. These disparate approaches create friction and distrust, even among groups that share a common goal of establishing Islamic governance. The Brotherhood’s participation in democratic processes in Egypt, for example, was met with skepticism and hostility from more radical factions, who viewed such engagement as a betrayal of Islamist principles. This lack of ideological unity weakens the movement’s ability to mobilize resources and maintain a consistent narrative.

Geopolitical interests further exacerbate these internal divisions. Islamist movements often become pawns in larger power struggles, as seen in the Syrian Civil War, where various Islamist groups aligned with different regional and global powers. Turkey, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, for instance, have backed different factions within the Syrian opposition, each with its own interpretation of political Islam. This external manipulation not only fragments the movement but also distracts from its core objectives, as local Islamist groups prioritize survival and funding over ideological purity or unity.

To address these internal divisions, Islamist movements must prioritize dialogue and reconciliation over ideological rigidity. A practical first step would be to establish cross-sectarian and cross-ideological forums where leaders can discuss shared goals and strategies. For example, initiatives like the “Mecca Document” in 2019, which aimed to foster unity among Muslim scholars, could serve as a blueprint for broader political cooperation. Additionally, Islamist groups should focus on grassroots mobilization that transcends sectarian and ideological lines, emphasizing issues like social justice and economic development that resonate universally within Muslim communities.

Ultimately, the failure to bridge these internal divides will continue to weaken political Islam’s unified front, rendering it ineffective in achieving its stated goals. Without a concerted effort to foster unity, the movement risks becoming a fragmented collection of competing interests, unable to present a credible alternative to secular or authoritarian governance. The challenge lies not in abandoning diversity but in harnessing it to create a more resilient and cohesive force.

Unveiling Political Funding: A Step-by-Step Guide to Tracing Donations

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Public disillusionment with Islamist parties in democratic elections

Across the Muslim world, a striking trend has emerged: voters who once enthusiastically supported Islamist parties are now turning away. In countries like Egypt, Tunisia, and Morocco, electoral setbacks for Islamist movements paint a picture of growing public disillusionment. This shift isn't merely a rejection of religious ideology but a complex reaction to unfulfilled promises, pragmatic governance failures, and evolving societal priorities.

Consider the case of Tunisia's Ennahda party. Once hailed as a model for moderate political Islam, Ennahda's popularity plummeted after years in power. Critics point to its inability to address chronic economic woes, rising unemployment, and perceived compromises on revolutionary ideals. Similarly, Egypt's Muslim Brotherhood, despite its initial electoral triumph, faced a swift backlash due to its perceived authoritarian tendencies and failure to deliver tangible improvements in Egyptians' daily lives. These examples illustrate a crucial lesson: voters who initially embraced Islamist parties for their moral appeal and anti-establishment stance are increasingly prioritizing competence and results over ideological purity.

The erosion of trust in Islamist parties is further exacerbated by internal divisions and strategic missteps. In many cases, these parties have struggled to balance their religious agendas with the demands of democratic governance. Their inability to effectively navigate the complexities of coalition-building, economic management, and social reform has left them vulnerable to criticism from both secular opponents and disillusioned supporters. This internal fragility, coupled with external pressures from authoritarian regimes and geopolitical rivalries, has further weakened their appeal.

However, it's crucial to avoid painting this trend with too broad a brush. Public disillusionment with Islamist parties doesn't necessarily signify a rejection of Islam's role in public life. Rather, it reflects a maturing electorate demanding accountability, transparency, and effective governance. Islamist movements that fail to adapt to these changing expectations risk becoming relics of a bygone era, while those that embrace pragmatism, inclusivity, and a focus on tangible results may yet find a path to renewed relevance.

Mastering Political Warfare: Strategies, Tactics, and Psychological Influence

You may want to see also

Secularization trends reducing political Islam's societal influence

Across the Muslim world, secularization is reshaping societal norms and diminishing the influence of political Islam. This trend manifests in various ways, from legal reforms to shifts in public attitudes, often driven by younger generations seeking individual freedoms over religious orthodoxy. Turkey, once a flagship of political Islam under the AKP, exemplifies this shift: recent polls show a majority of Turks now support a stricter separation of religion and state, while alcohol consumption rates—a barometer of secularization—have risen steadily since 2015.

Consider the mechanics of secularization: it operates not through outright rejection of faith, but by re-privatizing it. In Tunisia, post-Arab Spring reforms decriminalized apostasy and enshrined gender equality in inheritance laws, effectively sidelining Sharia-based interpretations. Such changes reflect a pragmatic approach where religious doctrine is no longer the default framework for governance. Even in conservative societies like Saudi Arabia, Vision 2030’s emphasis on economic diversification implicitly prioritizes global market norms over Wahhabi strictures, as evidenced by the reopening of cinemas and the lifting of the female driving ban.

However, secularization’s impact isn’t uniform. In Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim-majority nation, political Islam retains influence through parties like PKS, yet its support base is eroding. A 2022 survey by the Indonesian Survey Institute found that 62% of respondents aged 18–30 prioritize economic policies over religious platforms, a 12% increase from 2017. This demographic shift underscores a global pattern: as education levels rise and urbanization accelerates, religious identity becomes one factor among many, not the defining one.

To accelerate secularization’s impact, policymakers should focus on three levers: education reform, economic inclusion, and media pluralism. In Morocco, integrating critical thinking into school curricula has reduced support for Islamist parties among youth by 15% since 2010. Meanwhile, Malaysia’s push for women’s workforce participation—now at 55%—has correlated with declining support for Sharia-based legal systems. Caution is warranted, though: heavy-handed secularization, as seen in France’s hijab bans, can provoke backlash. The goal should be creating environments where religious and secular identities coexist without one dominating public life.

Ultimately, secularization is not about eradicating faith but recalibrating its role in society. Political Islam’s decline reflects a broader global trend where modernity demands flexibility, not dogma. As societies from Senegal to Bangladesh urbanize and connect digitally, the question isn’t whether secularization will continue, but how it can be managed equitably. The answer lies in policies that respect religious expression while ensuring it doesn’t dictate public policy—a balance increasingly demanded by the very populations political Islam once claimed to represent.

Urban Planning and Politics: Navigating the Intersection of Power and Design

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The success or failure of Political Islam depends on the context and goals defined. In some cases, it has achieved political power and implemented Sharia-based governance, as seen in Iran and parts of Sudan. However, in other regions, it has faced challenges such as internal divisions, authoritarian backlash, or failure to address economic and social issues, leading to mixed outcomes.

Critics argue that Political Islam has failed in modern societies due to its inability to adapt to democratic principles, address economic development, and provide inclusive governance. Its rigid interpretation of religious laws often clashes with pluralistic values, leading to alienation of minority groups and international isolation.

Political Islam's impact on stability and development varies. In some cases, it has contributed to social cohesion and moral frameworks, but in others, it has exacerbated conflicts, stifled innovation, and hindered economic growth. Its success or failure often hinges on leadership, policies, and the ability to balance religious ideals with practical governance.