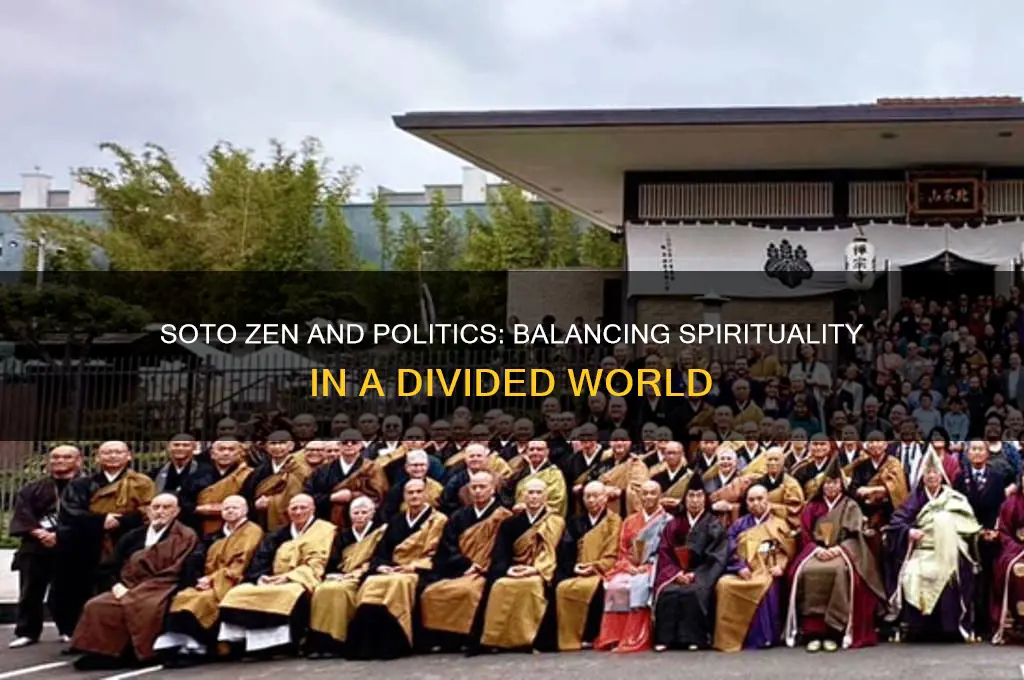

The question of whether Soto Zen has become too political has sparked considerable debate within Buddhist communities and beyond. Critics argue that some Soto Zen institutions and practitioners have increasingly engaged with social and political issues, such as environmental activism, racial justice, and LGBTQ+ rights, potentially diverting focus from traditional spiritual practices. Proponents, however, contend that such engagement aligns with the Bodhisattva ideal of compassion and the responsibility to alleviate suffering in the world. This tension highlights a broader struggle within Buddhism to balance its timeless teachings with the urgent demands of contemporary society, raising questions about the role of spirituality in addressing systemic issues and whether such involvement compromises the apolitical nature traditionally associated with Zen practice.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Soto Zen's historical ties to Japanese nationalism

The historical ties between Soto Zen and Japanese nationalism are deeply rooted in Japan's feudal and modern eras, reflecting a complex interplay between spiritual practice and political ideology. During the Kamakura period (1185–1333), Soto Zen was introduced to Japan by Eihei Dogen, who emphasized meditation and monastic discipline. However, it was during the Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1868) that Soto Zen became institutionalized, aligning with the state's efforts to consolidate power and promote social order. Temples served as administrative hubs, and monks often acted as record-keepers and mediators, effectively integrating Zen into the political machinery of the time.

One of the most striking examples of Soto Zen's entanglement with nationalism occurred during the Meiji Restoration (1868) and the subsequent rise of State Shinto. As Japan modernized and sought to assert itself on the global stage, the government promoted a fusion of Shinto and Buddhism to foster national unity and loyalty to the emperor. Soto Zen institutions, like other Buddhist sects, were pressured to conform to this agenda. Temples were encouraged to display the national flag and conduct rituals glorifying the emperor, blurring the line between religious practice and political indoctrination. This period marked a significant departure from Dogen's original teachings, which emphasized individual enlightenment over collective identity.

The role of Soto Zen in Japan's militarization during the early 20th century further underscores its political co-optation. During World War II, many Soto Zen leaders supported the war effort, framing it as a sacred duty to defend the nation. Monks were deployed as military chaplains, and temples became sites for promoting imperial propaganda. The infamous "War Responsibility Statement" issued by Japanese Buddhist leaders in 1945 acknowledged their complicity in justifying the war, though it stopped short of condemning the institution's role in fostering nationalism. This legacy continues to spark debates within Soto Zen communities about the ethical boundaries of religious engagement with political power.

To disentangle Soto Zen from its nationalist past, practitioners today must engage in critical self-reflection and historical education. This involves revisiting foundational texts like Dogen's *Shobogenzo* to reclaim the tradition's emphasis on mindfulness and compassion, rather than conformity. Modern Soto Zen communities can also adopt transparency measures, such as publicly addressing historical wrongs and committing to non-partisan spiritual practice. For instance, some temples now offer workshops on the history of Buddhism and nationalism, encouraging participants to explore how spiritual teachings can be misused for political ends.

In conclusion, while Soto Zen's historical ties to Japanese nationalism are undeniable, they need not define its future. By acknowledging this past and actively working to separate spiritual practice from political agendas, Soto Zen can reclaim its role as a path to personal liberation rather than a tool for collective manipulation. This process requires both institutional accountability and individual commitment, ensuring that the mistakes of the past do not overshadow the transformative potential of Zen practice.

Mastering the Art of Watching Political Debates: Tips and Strategies

You may want to see also

Monks' involvement in wartime propaganda and militarism

The role of Soto Zen monks in wartime propaganda and militarism is a stark reminder of how spiritual institutions can be co-opted for political ends. During World War II, Japanese Zen leaders, including those from the Soto school, actively supported the imperial government’s war efforts. Monks were enlisted to justify the war as a sacred duty, aligning it with Zen principles of discipline, self-sacrifice, and loyalty. This collaboration was not merely passive; it involved explicit teachings and sermons that framed military service as a path to enlightenment. For instance, the concept of *mu* (non-attachment) was reinterpreted to encourage soldiers to face death without fear, effectively weaponizing Zen philosophy for the battlefield.

To understand this phenomenon, consider the systemic pressures monks faced. The Japanese government’s *State Shinto* ideology merged religion and nationalism, leaving little room for dissent. Temples were financially dependent on state support, and monks who resisted risked persecution. However, this context does not absolve the Soto Zen establishment of responsibility. Leaders like Harada Daiun Sogaku and Yasutani Haku’un publicly endorsed militarism, with Harada even stating that “the Emperor’s will is the Buddha’s will.” Such statements reveal how deeply Zen institutions were entangled in the war machine, raising questions about the integrity of their teachings during this period.

A comparative analysis highlights the contrast between Soto Zen’s wartime actions and its post-war narrative. After Japan’s surrender, many monks distanced themselves from their past, emphasizing Zen’s apolitical nature. This shift raises concerns about accountability. While some, like Suzuki Daisetsu Teitaro, later criticized militarism, the lack of formal acknowledgment or apology from Soto Zen institutions remains notable. This erasure complicates efforts to reconcile Zen’s spiritual teachings with its historical complicity, leaving practitioners to grapple with a legacy of political entanglement.

For modern practitioners, this history serves as a cautionary tale. It underscores the importance of critical engagement with religious institutions, particularly when they intersect with political power. To avoid repeating past mistakes, practitioners should: (1) question how spiritual teachings are applied in societal contexts, (2) demand transparency from religious leaders, and (3) foster dialogue about the ethical responsibilities of spiritual communities. By doing so, Zen can reclaim its focus on personal liberation without becoming a tool for oppressive ideologies.

Ultimately, the involvement of Soto Zen monks in wartime propaganda challenges the notion of spirituality as inherently apolitical. It demonstrates how even the most introspective traditions can be manipulated to serve external agendas. This history invites practitioners to reflect not only on Zen’s past but also on its present role in a world where political and spiritual boundaries remain blurred. The takeaway is clear: vigilance and ethical inquiry are essential to preserving the integrity of any spiritual path.

Capitalizing Political Ideologies: Rules, Exceptions, and Common Mistakes Explained

You may want to see also

Modern Zen leaders' political statements and activism

Modern Zen leaders are increasingly stepping into the political arena, using their platforms to address social and environmental issues. Figures like Zen priest and author Rev. angel Kyodo williams have been vocal about racial justice, climate change, and economic inequality, often framing these issues as extensions of Buddhist teachings on suffering and interdependence. Her organization, Transformative Change, integrates Zen practice with activism, demonstrating how spiritual leaders can mobilize communities for systemic change. This blending of dharma and politics challenges traditional notions of monastic detachment, sparking debates about the role of religion in public life.

To engage in this intersection of Zen and politics effectively, consider these steps: first, study the principles of engaged Buddhism, a movement pioneered by Thich Nhat Hanh, which emphasizes mindfulness in action. Second, identify local or global issues that align with Buddhist values, such as compassion and non-harm. Third, collaborate with existing activist groups to amplify impact while maintaining a grounded, meditative approach. Caution against dogmatism; ensure your actions remain inclusive and avoid alienating those with differing views. Finally, reflect regularly on your motivations, ensuring they stem from genuine compassion rather than ego-driven righteousness.

Critics argue that politicizing Zen risks diluting its spiritual essence, turning monasteries into platforms for ideological agendas. However, proponents counter that silence in the face of injustice contradicts the bodhisattva ideal of alleviating suffering. For instance, the Plum Village community, inspired by Thich Nhat Hanh, has issued statements on issues like the Israel-Palestine conflict, grounding their stance in the Five Mindfulness Trainings. This approach illustrates how political engagement can be deeply rooted in practice, not merely reactive. The key is to balance advocacy with the core teachings of mindfulness and equanimity.

A comparative analysis reveals that while Rinzai Zen tends to maintain a more apolitical stance, Soto Zen, particularly in the West, has embraced activism more openly. Leaders like Zenki Shibayama and Joan Halifax have spoken out against nuclear weapons and environmental degradation, respectively, reflecting a broader trend of Soto Zen's adaptability to contemporary challenges. This divergence highlights the importance of cultural context in shaping religious expression. For practitioners, it underscores the need to critically examine how their lineage engages with the world, ensuring alignment with both tradition and personal values.

Practically, integrating Zen and activism requires a disciplined approach. Start with daily mindfulness practices to cultivate clarity and resilience. Allocate specific times for both meditation and advocacy to avoid burnout. For example, dedicate 30 minutes each morning to sitting practice, followed by 15 minutes of journaling on how your actions align with Buddhist principles. Engage in collective practices like peace walks or meditation vigils to strengthen community bonds. Remember, the goal is not to impose beliefs but to embody compassion in action, allowing your presence to be a transformative force in the world.

COVID-19: A Public Health Crisis or Political Tool?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Zen institutions' role in contemporary social justice movements

Soto Zen institutions, traditionally associated with meditation and spiritual practice, are increasingly engaging with contemporary social justice movements. This shift raises questions about the role of Zen in addressing systemic inequalities, environmental crises, and human rights issues. While some practitioners argue that Zen should remain apolitical, focusing solely on individual enlightenment, others contend that the core teachings of compassion and interconnectedness inherently call for social engagement. This tension highlights a broader debate within Zen communities about how to balance spiritual practice with active participation in societal transformation.

One practical example of Zen institutions aligning with social justice is the adoption of anti-racism training within monasteries and practice centers. For instance, the San Francisco Zen Center has implemented programs to address racial bias and promote inclusivity, recognizing that spiritual communities are not immune to systemic prejudices. These initiatives often include workshops, reading groups, and dialogue sessions aimed at fostering awareness and accountability. Such efforts demonstrate how Zen institutions can use their platforms to dismantle internal biases while contributing to broader societal change. However, critics caution that these programs must be sustained and deeply integrated into practice, not merely performative gestures.

Another area where Zen institutions are making an impact is environmental activism, rooted in the Buddhist principle of interdependence. Monasteries and practice centers are increasingly adopting sustainable practices, such as reducing waste, conserving energy, and promoting plant-based diets. Some, like the Zen Mountain Monastery in New York, have gone further by organizing retreats focused on eco-dharma, blending meditation with environmental stewardship. These actions reflect a growing recognition that spiritual practice cannot be separated from the health of the planet. Practitioners are encouraged to see environmental justice as a natural extension of their commitment to non-harming (ahimsa).

Despite these efforts, challenges remain. Engaging in social justice work can provoke internal divisions within Zen communities, particularly when political issues are polarizing. For example, statements on contentious topics like immigration or LGBTQ+ rights have sometimes led to disagreements among practitioners. Zen institutions must navigate these tensions carefully, ensuring that their actions align with the principles of compassion and inclusivity without alienating members. This requires skillful leadership and a commitment to dialogue, emphasizing unity in diversity.

In conclusion, the role of Soto Zen institutions in contemporary social justice movements is both promising and complex. By integrating anti-racism training, environmental activism, and other forms of engagement, these institutions are redefining what it means to practice Zen in the modern world. However, success depends on authenticity, consistency, and a willingness to confront internal challenges. As Zen communities continue to evolve, their contributions to social justice will likely deepen, offering a unique blend of spiritual wisdom and practical action. For practitioners, this means embracing the call to compassion not just on the cushion, but in the streets and systems of the world.

Divided We Stand: How Political Ideologies Fracture Societies and Fuel Polarization

You may want to see also

Balancing spiritual practice with political engagement in Soto Zen

Soto Zen, with its emphasis on mindfulness and non-attachment, often seems at odds with the heated, divisive world of politics. Yet, practitioners increasingly find themselves grappling with societal issues that demand attention. The question arises: how can one maintain the tranquility of zazen while engaging in the tumult of political activism? The key lies in understanding that Soto Zen’s core teachings—such as *shikantaza* (just sitting)—are not escapes from reality but tools for deeper engagement. By cultivating present-moment awareness, practitioners can approach political issues with clarity, compassion, and equanimity, avoiding the pitfalls of reactivity or dogmatism.

Consider the practice of *beginner’s mind*, a Soto Zen principle encouraging openness and curiosity. Applied to political engagement, this mindset fosters dialogue rather than debate, listening rather than lecturing. For instance, instead of immediately advocating for a specific policy, a practitioner might first seek to understand the experiences of those affected by the issue. This approach aligns with Thich Nhat Hanh’s concept of "mindful politics," where actions are rooted in awareness rather than ideology. Practical steps include setting aside 10 minutes daily to reflect on one’s political beliefs, examining biases, and identifying areas where compassion can guide action.

However, balancing spiritual practice with political engagement requires caution. The risk of co-opting Zen teachings to justify political agendas is real. For example, emphasizing non-attachment might be misconstrued as apathy, while advocating for social justice could be seen as abandoning the middle way. To mitigate this, practitioners should regularly return to the *precepts*, particularly the commitment to refrain from harmful speech and action. Engaging in political discourse without anger or judgment is a practice in itself, akin to maintaining posture during zazen. A useful exercise is to pause before speaking or posting online, asking: "Is this statement kind, true, and necessary?"

Comparatively, other Buddhist traditions offer insights. Engaged Buddhism, popularized by figures like the Dalai Lama, explicitly links spiritual practice with social action. While Soto Zen’s approach is subtler, it shares the goal of alleviating suffering. For instance, Zen Master Dogen’s teachings on interdependence (*dependent origination*) underscore the interconnectedness of all beings, providing a philosophical foundation for political engagement. Practitioners can draw on this by framing activism as an extension of their practice, not a departure from it. A tangible way to integrate this is by dedicating 20% of one’s meditation time to reflecting on how to apply Zen principles to current issues.

Ultimately, balancing spiritual practice with political engagement in Soto Zen is about embodying mindfulness in action. It’s not about becoming a Zen activist but about letting Zen inform one’s activism. This requires intentionality—setting clear boundaries, such as limiting time spent on political activities to avoid burnout, and prioritizing self-care through regular practice. By viewing political engagement as a form of *practice*, Soto Zen practitioners can remain grounded in their spiritual path while contributing meaningfully to societal change. The takeaway? Spirituality and politics need not be at odds; when approached mindfully, they can be complementary paths toward a more compassionate world.

Does Soliciting Include Political Groups? Legal Boundaries Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Soto Zen, as a spiritual tradition, is not inherently political. Its primary focus is on meditation, mindfulness, and the realization of one's true nature, rather than engaging in political ideologies or systems.

Some Soto Zen practitioners and teachers may engage in social or political activism based on their personal beliefs, but this is not a requirement or official stance of the tradition itself.

Historically, Soto Zen in Japan has had periods of entanglement with political power structures, particularly during feudal times when temples were supported by the ruling class. However, this does not define the core teachings or practice of Soto Zen.

Soto Zen principles, such as compassion and non-attachment, can inform how individuals approach political issues, but the tradition itself does not prescribe specific political positions or actions.

There are varying opinions among practitioners about whether and how Soto Zen should engage with political or social issues. Some advocate for active involvement, while others emphasize maintaining a focus on spiritual practice.