The Constitution of the United States does not outline a specific role for the President in the process of amending the Constitution. While some Presidents have played a ministerial role in transmitting Congress's proposed amendments to the states for ratification, their signature is not required for the proposal or ratification of an amendment. The authority to amend the Constitution is derived from Article V of the Constitution, which allows for amendments to be proposed by Congress with a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. The process of amending the Constitution involves Congress proposing an amendment, followed by the Archivist of the United States, who is responsible for certifying a state's ratification. While the President may witness the certification of an amendment, their agreement is not a requirement for amending the Constitution.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Does the President have a formal role in amending the Constitution? | No |

| Does the President have an informal role in amending the Constitution? | Yes |

| Who is responsible for proposing an amendment? | Congress |

| What is the required majority for proposing an amendment? | Two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate |

| Who is responsible for administering the ratification process? | The Archivist of the United States |

| Who has played a role in transmitting Congress's proposed amendments to the states for ratification? | Presidents like George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Jimmy Carter |

| Can the President veto a proposed amendment? | No |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The President's signature is not required

The US Constitution does not outline a specific role for the President in the process of amending the Constitution. The Supreme Court has also articulated the Judicial Branch's understanding that the President has no formal constitutional role in amending the Constitution. In the 1920 case of Hawke v. Smith, the Supreme Court affirmed its earlier decision in Hollingsworth v. Virginia (1798), which held that the submission of a constitutional amendment did not require the action of the President.

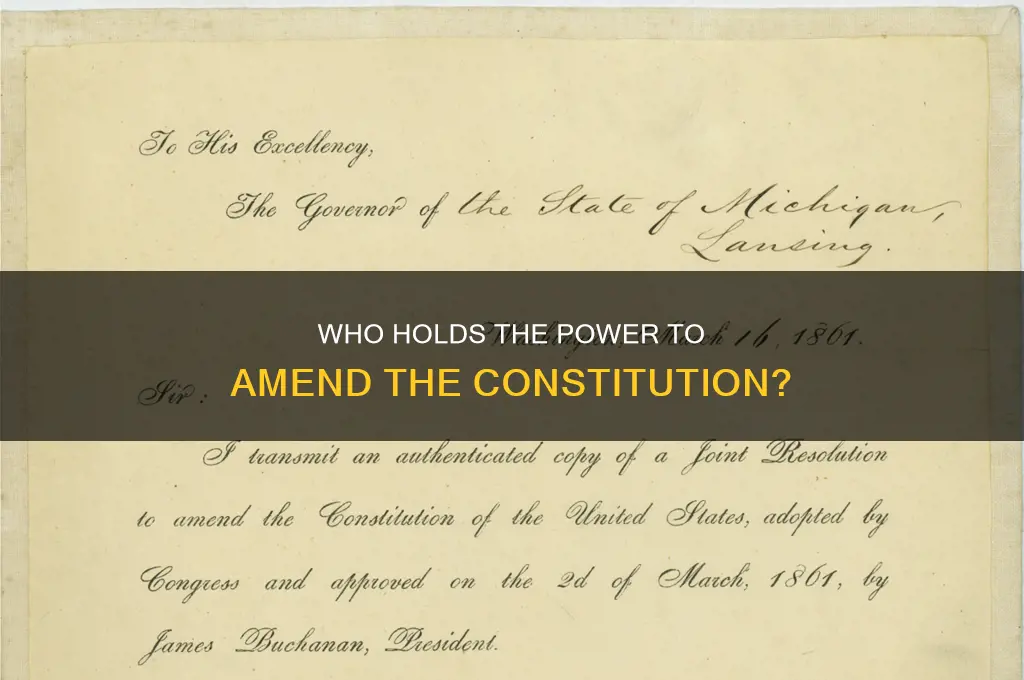

Despite this, some Presidents have played an informal, ministerial role in the amendment process by transmitting Congress's proposed amendments to the states for potential ratification. For example, President George Washington sent the first twelve proposed amendments, including the ten proposals that later became the Bill of Rights, to the states for ratification after Congress approved them. Additionally, President Abraham Lincoln signed the joint resolution proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish slavery, even though his signature was not necessary for its proposal or ratification. Similarly, President Jimmy Carter signed a joint resolution to extend the deadline for ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment, despite being advised that his signature was unnecessary.

In modern times, the Archivist of the United States is responsible for certifying a state's ratification of a constitutional amendment. The certification process has, in recent history, become a ceremonial function attended by various dignitaries, including the President. For example, President Johnson signed the certifications for the 24th and 25th Amendments as a witness, and President Nixon witnessed the certification of the 26th Amendment.

Therefore, while the President's signature is not required to amend the Constitution, Presidents have occasionally played a ceremonial or ministerial role in the amendment process.

Voting Age Amendment: The Power to the Youth

You may want to see also

The President can play a ministerial role

The President of the United States does not have to agree to amend the Constitution. The Constitution does not outline a specific role for the President in the amendment process. The Supreme Court has also articulated the view that the President has no formal role in amending the Constitution.

However, some Presidents have played a ministerial role in transmitting Congress's proposed amendments to the states for potential ratification. For example, President George Washington sent the first twelve proposed amendments, including the ten proposals that later became the Bill of Rights, to the states for ratification after Congress approved them. Similarly, President Abraham Lincoln signed the joint resolution proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish slavery, even though his signature was not necessary for its proposal or ratification.

In modern times, the Archivist of the United States is responsible for certifying a state's ratification of a constitutional amendment. However, in recent history, the signing of the certification has become a ceremonial function that may include the President. For instance, President Johnson signed the certifications for the 24th and 25th Amendments as a witness, and President Nixon witnessed the certification of the 26th Amendment.

Furthermore, the President cannot veto a proposed amendment. For example, President Jimmy Carter signed a joint resolution to extend the deadline for the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment, despite being advised that his signature was unnecessary.

The Fifth Amendment: Protecting Your Right to Remain Silent

You may want to see also

The Supreme Court's view on the President's role

The Supreme Court is the highest court in the United States, and it plays a crucial role in the country's constitutional system of government. The Court has the power of judicial review, which allows it to ensure that each branch of the government recognizes its power limits. Additionally, it protects civil rights and liberties by striking down laws that violate the Constitution.

In the context of the President's role in amending the Constitution, the Supreme Court has articulated the view that the President does not have a formal constitutional role in the amendment process. This interpretation was established in the 1798 case of Hollingsworth v. Virginia, where the Court held that the Eleventh Amendment had been "constitutionally adopted" without requiring the President's action.

In the 1920 case of Hawke v. Smith, the Supreme Court reaffirmed this position by characterizing its earlier decision in Hollingsworth as settling that the submission of a constitutional amendment did not necessitate the involvement of the President. The Court's ruling in Hawke v. Smith indicated that the President cannot veto a proposed amendment.

While the President has no formal role in amending the Constitution, they may play an informal and ministerial role in the process. For example, President Abraham Lincoln signed the joint resolution proposing the Thirteenth Amendment, even though his signature was not required. Similarly, President Jimmy Carter signed a joint resolution regarding the Equal Rights Amendment, despite being advised that his signature was unnecessary. These instances demonstrate the Supreme Court's recognition that the President's participation in amending the Constitution is not mandatory but can be discretionary.

In summary, the Supreme Court's view on the President's role in amending the Constitution is clear. The Court has consistently held that the President has no formal constitutional role in the amendment process, as established in Hollingsworth v. Virginia and reaffirmed in Hawke v. Smith. However, the President may occasionally play an informal or ceremonial role, as seen in the examples of Presidents Lincoln and Carter. Ultimately, the Supreme Court's interpretation ensures that the amendment process remains within the domain of Congress and the states, without requiring executive involvement.

Amending Rights: Understanding the Fourth Amendment

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The President's role in the certification process

The President does not have a formal role in amending the Constitution. The Supreme Court has explicitly stated that the President has no formal constitutional role in the amendment process. This was articulated in the 1798 case Hollingsworth v. Virginia and reaffirmed in Hawke v. Smith in 1920.

However, some Presidents have played an informal and ministerial role in transmitting Congress's proposed amendments to the states for potential ratification. For example, President George Washington sent the first twelve proposed amendments, including the ten proposals that became the Bill of Rights, to the states for ratification after Congress approved them. Similarly, President Abraham Lincoln signed the joint resolution proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish slavery, even though his signature was not required for its proposal or ratification.

In modern times, the certification of a state's ratification of a constitutional amendment falls under the responsibility of the Archivist of the United States, who heads the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). The Archivist has delegated many of the ministerial duties to the Director of the Federal Register. The certification process includes drafting a formal proclamation and publishing it in the Federal Register and U.S. Statutes at Large, serving as official notice that the amendment process is complete.

While not a constitutional requirement, in recent history, the President has been included in the ceremonial function of signing the certification as a witness. President Johnson signed the certifications for the 24th and 25th Amendments, and President Nixon witnessed the certification of the 26th Amendment.

Capitalizing Amendments: Understanding Constitutional Style Rules

You may want to see also

Congress's role in proposing an amendment

The US Constitution does not establish a role for the President in amending the Constitution. The President does not have a constitutional role in the amendment process, and the joint resolution does not go to the White House for signature or approval. The original document is forwarded directly to NARA's Office of the Federal Register (OFR) for processing and publication.

Congress plays a significant role in proposing an amendment to the Constitution. Whenever two-thirds of both Houses deem it necessary, Congress shall propose Amendments to the Constitution. This can be done through a joint resolution, which requires a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. Congress has followed this procedure to propose constitutional amendments, which are then sent to the states for potential ratification.

Alternatively, Article V provides that Congress shall call a convention for proposing amendments upon the request of two-thirds of the states. This method of proposing amendments has never been used. Congress may also set a reasonable time limit for the ratification of an amendment.

Once an amendment is proposed by Congress, the Archivist of the United States, who heads the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), is responsible for administering the ratification process. The Archivist submits the proposed amendment to the states for their consideration, and the governors then formally submit it to their state legislatures. When a state ratifies the amendment, it sends the Archivist an original or certified copy, which is conveyed to the Director of the Federal Register.

While the President does not have a formal constitutional role in amending the Constitution, some Presidents have played a ministerial role in transmitting Congress's proposed amendments to the states for potential ratification. For example, President George Washington sent the first twelve proposed amendments, including the ten proposals that became the Bill of Rights, to the states for ratification after Congress approved them. Additionally, President Abraham Lincoln signed the joint resolution proposing the Thirteenth Amendment, and President Jimmy Carter signed a joint resolution extending the deadline for ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment, even though their signatures were not necessary. In recent history, the President may be present during the ceremonial function of signing the certification of an amendment.

The Architects of Constitutional Amendments: Understanding the Framers

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, the President does not have a constitutional role in the amendment process. The Constitution does not establish a role for the President in amending the Constitution.

Yes, while not constitutionally required, Presidents have played an informal, ministerial role in the amendment process. For example, President Abraham Lincoln signed the joint resolution proposing the Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery.

An amendment may be proposed by Congress with a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, or by a constitutional convention called for by two-thirds of the State legislatures. The Archivist of the United States is responsible for certifying a state's ratification of an amendment.

Yes, the Twenty-second Amendment established term limits for the Presidency, limiting individuals to two terms in office. This amendment was ratified in 1951.

![The First Amendment: [Connected Ebook] (Aspen Casebook) (Aspen Casebook Series)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61p49hyM5WL._AC_UY218_.jpg)