The question of whether the European Council (EC) encourages two-party politics is a nuanced one, as the EC operates within the broader framework of the European Union’s multi-party system. Unlike national systems where two-party dominance is more evident, the EC’s structure and decision-making processes are designed to accommodate diverse political groups and coalitions. While the EC’s leadership roles, such as the President of the European Council, often rotate among major political families like the European People’s Party (EPP) and the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D), this does not inherently promote a two-party system. Instead, the EC’s emphasis on consensus-building and inclusivity reflects the EU’s commitment to representing a wide spectrum of political ideologies. Thus, while certain dynamics may favor larger parties, the EC’s role is more about fostering cooperation across multiple parties rather than consolidating power into a two-party framework.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

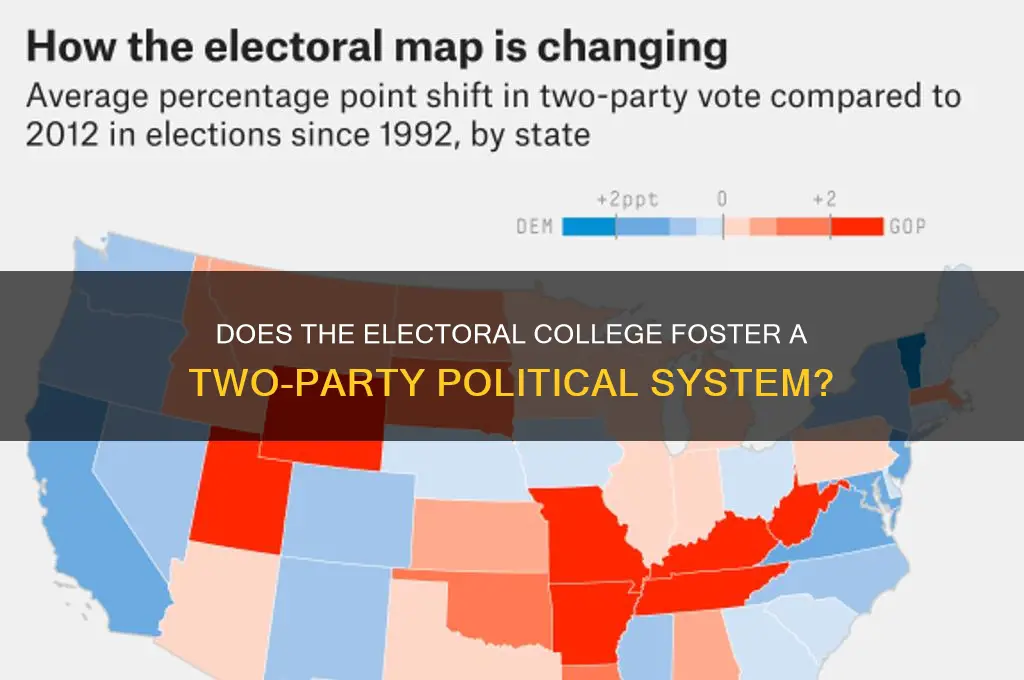

| Electoral System | The EC (Electoral College) in the U.S. does not directly encourage two-party politics, but the winner-take-all system in most states tends to favor the emergence of two dominant parties. |

| Duverger's Law | The EC system aligns with Duverger's Law, which suggests that plurality voting systems (like the EC) often lead to a two-party system by discouraging smaller parties. |

| Third-Party Challenges | The EC makes it difficult for third parties to gain traction, as they rarely win electoral votes, further solidifying the two-party dominance. |

| Strategic Voting | Voters often strategically vote for the "lesser of two evils" to avoid "wasting" their vote on a third-party candidate who is unlikely to win electoral votes. |

| Historical Precedent | The U.S. has had a two-party system for most of its history, and the EC has been a contributing factor by marginalizing smaller parties. |

| State-Level Dynamics | The winner-take-all allocation of electoral votes in 48 states and Washington D.C. discourages third-party candidates from competing seriously in most states. |

| National Focus | The EC system encourages parties to focus on swing states, further limiting the viability of third parties that lack broad national appeal. |

| Electoral College Reform | Proposals to reform the EC (e.g., the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact) could potentially alter its impact on two-party politics, but such reforms are not yet widespread. |

| Party Polarization | The EC system can exacerbate party polarization by incentivizing candidates to appeal to the extremes of their party in key states rather than moderates nationwide. |

| Representation | Smaller parties and independent candidates are often underrepresented in the EC system, as they struggle to secure electoral votes. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- EC's Role in Electoral Systems: How EC's rules favor major parties over smaller ones

- Funding and Resources: EC's allocation of funds disproportionately benefits established parties

- Media Coverage Rules: EC guidelines often prioritize two-party narratives in elections

- Ballot Access Barriers: Strict EC regulations limit smaller parties' ability to compete

- Debate Participation Criteria: EC rules exclude minor parties from key political debates

EC's Role in Electoral Systems: How EC's rules favor major parties over smaller ones

The Electoral Commission (EC) plays a pivotal role in shaping electoral systems, and its rules often have a significant impact on the balance of power between major and smaller political parties. While the EC's primary goal is to ensure fair and transparent elections, certain regulations and practices can inadvertently favor established parties, potentially encouraging a two-party dominant political landscape. This phenomenon is particularly evident in various aspects of the electoral process, from candidate registration to campaign financing.

One of the key ways ECs influence party dynamics is through candidate nomination and registration processes. In many jurisdictions, the EC sets criteria for political parties to field candidates, which may include signature requirements, registration fees, or specific organizational structures. These barriers can be more easily navigated by larger parties with established networks and resources, making it challenging for smaller, emerging parties to gain a foothold. For instance, a stringent signature collection process might favor well-known parties with a broad support base, while newer parties struggle to meet the threshold, thus limiting voter choice.

Furthermore, the allocation of campaign resources and media coverage often leans towards major parties. ECs typically oversee campaign financing regulations, and while these rules aim to ensure fairness, they can sometimes disadvantage smaller parties. Larger parties with substantial financial backing can more easily comply with complex funding regulations and afford the associated administrative costs. They also tend to receive disproportionate media attention, as news outlets focus on the perceived front-runners, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of visibility and support. This imbalance in resources and publicity makes it arduous for smaller parties to compete effectively, thereby perpetuating the dominance of the major players.

The design of electoral systems, often influenced by EC recommendations, can also contribute to the marginalization of smaller parties. For example, in winner-takes-all or first-past-the-post systems, where the candidate with the most votes wins, smaller parties may struggle to secure representation even with a significant portion of the vote. This encourages strategic voting, where voters might opt for a major party to avoid 'wasting' their vote, further solidifying the two-party structure. Proportional representation systems, on the other hand, can provide smaller parties with a fairer chance of gaining seats, but the implementation and specifics of such systems are crucial and often subject to EC guidelines.

In addition, the EC's role in constituency delimitation and redistricting can impact the fortunes of smaller parties. Gerrymandering, whether intentional or not, can dilute the voting power of supporters of smaller parties, making it harder for them to win seats. Fair and regular redistricting processes, overseen by the EC, are essential to ensuring that all parties have an equal opportunity to compete. However, the criteria and methods used for redistricting can sometimes favor incumbent parties, making it a critical area where EC decisions directly affect the political landscape.

In summary, while the EC's primary mandate is to uphold electoral integrity, its rules and regulations can inadvertently create an environment that favors major political parties. From candidate registration to campaign financing and electoral system design, these factors collectively contribute to a political climate that may discourage the growth of smaller parties. Recognizing these dynamics is essential for fostering a more inclusive and diverse political arena, where the EC's role is not only to manage elections but also to actively promote a level playing field for all participants. This includes regular reviews of electoral laws and practices to identify and rectify any inherent biases.

How Political Parties Influence Voter Decisions Through Strategic Cues

You may want to see also

Funding and Resources: EC's allocation of funds disproportionately benefits established parties

The European Commission (EC) plays a significant role in shaping the political landscape of the European Union (EU) through its allocation of funds and resources. One of the key concerns is whether the EC's funding mechanisms inadvertently encourage a two-party political system by disproportionately benefiting established parties. This issue is particularly relevant when examining the distribution of financial resources, which can significantly impact the ability of smaller or emerging parties to compete effectively in elections and maintain a presence in the political arena.

The EC provides funding to political parties at both the European and national levels through various programs, such as the European Parliament’s political party funding scheme. While these funds are intended to support democratic participation and pluralism, the criteria for allocation often favor parties that already have a strong presence and organizational infrastructure. Established parties typically have larger memberships, more extensive networks, and a track record of electoral success, which are factors considered in the funding allocation process. This creates a cycle where well-resourced parties receive more funding, further solidifying their dominance and making it harder for smaller parties to gain traction.

Another aspect of this disparity is the indirect support provided through campaign financing rules and public funding mechanisms. In many EU member states, public funding for political parties is tied to their electoral performance, such as the number of votes received or seats won. This system inherently advantages established parties, as they are more likely to achieve higher vote shares and secure more seats. Smaller parties, even if they represent significant segments of the population, often struggle to meet the thresholds required to access these funds, perpetuating their marginalization.

Furthermore, the EC’s emphasis on fostering European-level political parties and foundations, such as those recognized under the European Political Parties and European Political Foundations Regulation, tends to benefit larger, more established organizations. These entities must meet specific criteria, including representation in a certain number of member states, which smaller parties often find difficult to fulfill. As a result, the majority of funding goes to a limited number of well-established parties, reinforcing their dominance and limiting the diversity of political voices at the European level.

Critics argue that this funding structure undermines the principles of fairness and equality in democratic competition. By disproportionately allocating resources to established parties, the EC inadvertently stifles political innovation and reduces opportunities for new or smaller parties to emerge and challenge the status quo. This dynamic can lead to a two-party or oligopolistic political system, where a few dominant parties control the majority of resources and influence, leaving limited space for alternative perspectives and representation.

To address this issue, reforms could include introducing more equitable funding criteria, such as allocating a portion of resources based on a party’s potential to contribute to political diversity rather than solely on past performance. Additionally, providing targeted support for smaller parties, such as capacity-building programs or seed funding, could help level the playing field. By reevaluating its funding mechanisms, the EC could play a more balanced role in promoting a pluralistic and inclusive political environment, rather than inadvertently encouraging a two-party system.

The Rise of the Do Nothing Party: A Political Paradox

You may want to see also

Media Coverage Rules: EC guidelines often prioritize two-party narratives in elections

The Election Commission (EC) of India plays a pivotal role in shaping the media landscape during elections, and its guidelines often inadvertently prioritize two-party narratives. This phenomenon is not explicitly stated in the EC’s rules but emerges from the practical implementation of media coverage regulations. The EC mandates equal coverage for recognized national and state parties, which typically include the two major political parties—the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Indian National Congress (INC). This focus on recognized parties, while aimed at fairness, tends to marginalize smaller parties and independent candidates, reinforcing a two-party-centric discourse in media reporting.

One of the key EC guidelines that contributes to this bias is the allocation of free airtime on public broadcasters like Doordarshan and All India Radio. These slots are disproportionately given to recognized parties, leaving limited space for others. Since media houses often follow the EC’s lead, private channels also prioritize coverage of the two major parties, amplifying their voices and policies. This creates a feedback loop where smaller parties struggle to gain visibility, and the electorate is predominantly exposed to a binary political narrative.

Additionally, the EC’s model code of conduct, which governs campaign coverage, emphasizes the activities of major parties. Media outlets, bound by these rules, focus on high-profile rallies, statements, and controversies involving the BJP and INC. While this is not explicitly a two-party promotion, the practical effect is a skewed representation that sidelines other contenders. The EC’s intent to ensure balanced coverage thus paradoxically reinforces the dominance of the two major parties in the public discourse.

Another factor is the EC’s approach to paid political advertisements. The guidelines require transparency and fairness, but the cost of airtime favors parties with larger financial resources—typically the BJP and INC. Smaller parties, unable to compete financially, are further pushed to the margins. This financial barrier, combined with the EC’s focus on recognized parties, inadvertently cements the two-party narrative in media coverage.

Critics argue that the EC’s guidelines, while well-intentioned, fail to address the structural inequalities in media representation. By prioritizing recognized parties, the EC inadvertently limits the diversity of political voices, reducing elections to a contest between two major players. This not only undermines the democratic principle of equal opportunity but also shapes voter perception by presenting a simplified, binary choice. To foster a more inclusive political discourse, the EC could consider revising its guidelines to ensure proportional representation for all parties, regardless of their size or recognition status.

In conclusion, while the EC does not explicitly encourage two-party politics, its media coverage rules often have this effect. The emphasis on recognized parties, combined with practical constraints like airtime allocation and financial resources, results in a media landscape dominated by the BJP and INC. Addressing this imbalance requires a reevaluation of the EC’s guidelines to promote a more equitable and diverse political narrative during elections.

Are Political Parties Civil Society? Exploring Roles, Boundaries, and Impact

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$86.08 $109.99

$45.83 $54.99

Ballot Access Barriers: Strict EC regulations limit smaller parties' ability to compete

The Electoral Commission (EC) in various countries often implements regulations that, while aimed at ensuring electoral integrity and fairness, can inadvertently create significant barriers for smaller political parties. These ballot access barriers are particularly stringent in systems where the EC enforces strict rules regarding candidate nomination, financial compliance, and administrative procedures. For smaller parties with limited resources, these requirements can be prohibitively difficult to meet, effectively limiting their ability to compete in elections. This dynamic often reinforces a two-party political system, as larger, more established parties are better equipped to navigate and comply with these regulations.

One of the primary ballot access barriers imposed by the EC is the nomination process. In many jurisdictions, candidates must gather a substantial number of signatures from registered voters to qualify for the ballot. While this requirement is ostensibly designed to ensure candidates have a minimum level of public support, it disproportionately disadvantages smaller parties. Larger parties, with their extensive networks and resources, can easily mobilize supporters to collect signatures, whereas smaller parties often struggle to meet these thresholds. This creates an uneven playing field, where only parties with significant organizational capacity can secure ballot access.

Financial compliance is another critical area where strict EC regulations hinder smaller parties. Election laws often mandate that parties and candidates submit detailed financial reports, pay registration fees, and adhere to spending limits. For smaller parties operating on shoestring budgets, these financial obligations can be insurmountable. Additionally, the EC may require parties to demonstrate a certain level of financial stability or fundraising capability, further marginalizing those with limited donor bases. As a result, smaller parties are often forced to divert scarce resources away from campaigning and toward administrative compliance, weakening their ability to compete effectively.

Administrative hurdles also play a significant role in limiting smaller parties' access to the ballot. The EC frequently imposes tight deadlines for filing paperwork, which can be challenging for parties without dedicated staff or legal expertise. Errors or delays in submitting required documents can lead to disqualification, effectively ending a party's electoral aspirations. Moreover, the complexity of election laws and regulations often requires professional legal assistance, an expense that smaller parties cannot afford. These administrative barriers not only exclude smaller parties from the electoral process but also reinforce the dominance of larger, more established parties.

In conclusion, strict EC regulations, while intended to maintain electoral integrity, often function as ballot access barriers that limit smaller parties' ability to compete. Through onerous nomination requirements, financial compliance mandates, and administrative hurdles, these regulations create an environment that favors larger, resource-rich parties. This dynamic inadvertently encourages a two-party political system, as smaller parties are systematically excluded from meaningful participation. To foster a more inclusive and competitive political landscape, it is essential to reevaluate and reform these regulations, ensuring that they do not disproportionately burden parties with limited resources.

Did Eisenhower Warn About Political Parties' Influence on Democracy?

You may want to see also

Debate Participation Criteria: EC rules exclude minor parties from key political debates

The Election Commission's (EC) debate participation criteria have long been a subject of contention, particularly regarding their impact on minor political parties. The EC's rules often set stringent thresholds for inclusion in key political debates, such as requiring parties to have a minimum number of sitting members in Parliament or a certain percentage of votes in previous elections. While these criteria are ostensibly designed to ensure meaningful and manageable debates, they effectively exclude minor parties, raising questions about whether the EC inadvertently encourages a two-party political system. This exclusion limits the visibility and influence of smaller parties, stifling diverse political voices and reducing the electorate's exposure to alternative ideologies.

Critics argue that the EC's debate participation rules disproportionately favor established parties, often the two largest ones, at the expense of newcomers or smaller factions. By setting high bars for entry, such as a 5% vote share or a specific number of elected representatives, the EC creates a cycle where minor parties struggle to gain traction. Without access to high-profile debates, these parties are denied a crucial platform to articulate their policies, connect with voters, and challenge the status quo. This dynamic reinforces the dominance of major parties, as they enjoy greater media exposure and public engagement, further marginalizing smaller contenders.

Proponents of the EC's criteria, however, contend that these rules are necessary to maintain the efficiency and relevance of political debates. Including too many parties, they argue, could lead to chaotic and unproductive discussions, diluting the focus on key issues. Additionally, they claim that minor parties often lack the organizational structure or policy depth to contribute meaningfully to national debates. From this perspective, the EC's thresholds act as a quality control mechanism, ensuring that only parties with demonstrable public support and political viability participate in high-stakes forums.

Despite these arguments, the exclusion of minor parties from key debates has significant democratic implications. It limits the electorate's ability to make informed choices by restricting access to a full spectrum of political ideas. In a healthy democracy, voters should have the opportunity to consider a range of perspectives, not just those of the dominant parties. The EC's rules, while intended to streamline debates, may inadvertently suppress political pluralism and innovation, reinforcing a two-party system that leaves little room for alternative voices.

To address these concerns, some suggest reforming the debate participation criteria to be more inclusive. For instance, the EC could adopt a tiered system, allowing minor parties to participate in preliminary or regional debates before advancing to national platforms. Alternatively, lowering the threshold for inclusion or introducing a lottery system for minor parties could provide them with a fair chance to engage with the public. Such reforms would not only level the playing field but also enrich the democratic process by fostering greater diversity in political discourse.

In conclusion, the EC's debate participation criteria, while aimed at ensuring efficient and focused discussions, have the unintended consequence of excluding minor parties from key political debates. This exclusion raises questions about whether the EC encourages a two-party system by limiting the visibility and influence of smaller factions. Reforming these criteria to be more inclusive could enhance democratic participation, ensure a broader representation of ideas, and provide voters with a more comprehensive understanding of their political choices. The challenge lies in balancing the need for manageable debates with the imperative to uphold political pluralism and fairness.

Jackson’s Presidency: The Resurgence of Political Parties in America

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, the EC system tends to favor two-party politics due to its winner-take-all method in most states, which marginalizes smaller parties and incentivizes strategic voting for major party candidates.

The EC’s structure makes it difficult for third-party candidates to win electoral votes, as they rarely secure a plurality in any state, leading to their exclusion from meaningful competition.

Yes, reforms like proportional allocation of electoral votes or the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact could reduce the two-party dominance by giving smaller parties a better chance to influence outcomes.

Smaller parties struggle because the winner-take-all approach in most states discourages voters from supporting them, as votes for third-party candidates are often seen as "wasted" in terms of electoral votes.

Yes, the EC’s emphasis on two-party competition in presidential elections spills over into congressional and state-level races, as parties align with the dominant presidential candidates to maximize their influence.