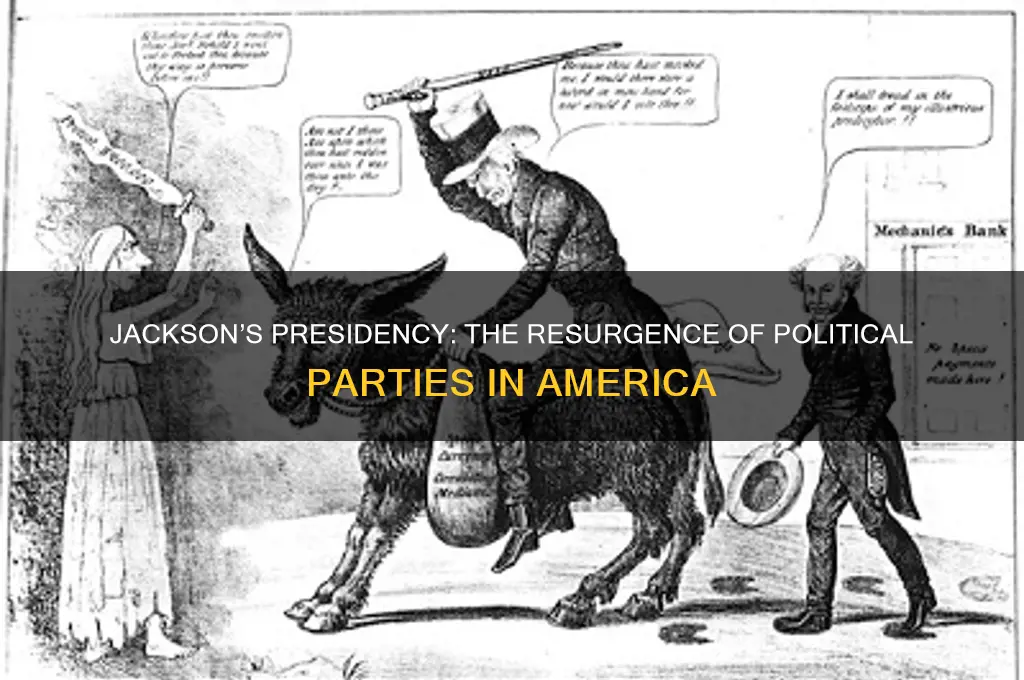

The question of whether political parties reappeared during Andrew Jackson's presidency is a significant one, as it marks a pivotal moment in American political history. Jackson's election in 1828 is often seen as a turning point, as it signaled the decline of the Era of Good Feelings and the reemergence of partisan politics. While the traditional party system had seemingly dissolved under James Monroe's administration, Jackson's rise to power reignited political divisions, ultimately leading to the formation of the modern two-party system. The Democratic Party, with Jackson as its figurehead, and the opposing Whig Party began to take shape, setting the stage for a new era of political competition and ideological debate in the United States.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Parties Before Jackson | Two-party system dominated by Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. |

| Jackson's Presidency (1829-1837) | Saw the emergence of the modern two-party system. |

| New Parties Formed | Democratic Party (led by Jackson) and Whig Party (opposition to Jackson). |

| Issues Driving Party Formation | Bank of the United States, states' rights, and economic policies. |

| Role of Jackson | His populist appeal and policies polarized politics, fostering party realignment. |

| Impact on Political Landscape | Solidified the two-party system that continues to shape U.S. politics. |

| Historical Context | Occurred during the Second Party System (1828-1854). |

| Key Figures | Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun. |

| Electoral Changes | Expansion of suffrage and increased voter participation. |

| Legacy | Established the framework for modern American political parties. |

Explore related products

$12.49 $12.49

What You'll Learn

- Emergence of Democratic Party under Jackson's leadership, reshaping American political landscape

- Whig Party Formation as opposition to Jackson's policies and centralization of power

- Role of Spoils System in party loyalty and patronage during Jackson's presidency

- Sectionalism and Parties how regional interests influenced party realignment in the 1830s

- Jackson's Populism appeal to common voters and its impact on party identity

Emergence of Democratic Party under Jackson's leadership, reshaping American political landscape

The emergence of the Democratic Party under Andrew Jackson's leadership marked a pivotal moment in American political history, reshaping the nation's political landscape in profound ways. Jackson's presidency, which began in 1829, coincided with the decline of the First Party System and the rise of a new era of mass politics. His charismatic leadership and populist appeal galvanized supporters who saw him as a champion of the common man against the elite. This movement laid the foundation for the Democratic Party, which would become one of the two dominant political parties in the United States. Jackson's ability to mobilize diverse groups, including farmers, workers, and western settlers, transformed American politics by broadening the base of political participation and challenging the dominance of the established elite.

Central to the emergence of the Democratic Party was Jackson's opposition to what he perceived as the concentration of power in the federal government and financial institutions, particularly the Second Bank of the United States. His veto of the Bank's recharter in 1832 became a defining issue, rallying his supporters around the idea of limiting federal authority and protecting states' rights. This stance resonated with many Americans who feared centralized power and favored a more decentralized government. The Democratic Party, under Jackson's leadership, embraced these principles, positioning itself as the party of the people against the interests of the wealthy and privileged. This ideological framework not only solidified the party's identity but also set the stage for future political debates over the role of government.

Jackson's leadership also reshaped the political landscape by fostering a new style of campaigning and party organization. His supporters employed innovative tactics, such as mass rallies, parades, and the use of partisan newspapers, to mobilize voters and spread their message. This marked a shift from the more elitist and less organized politics of the past, as the Democratic Party became a vehicle for mass participation. Jackson's presidency saw the rise of party conventions and the establishment of local and state party organizations, which further institutionalized the Democratic Party and ensured its longevity. This organizational structure allowed the party to maintain its influence long after Jackson left office.

The Democratic Party's emergence under Jackson also had significant implications for the two-party system in the United States. By rallying opposition to the Whig Party, which represented the interests of bankers, industrialists, and the old elite, the Democrats created a clear ideological divide in American politics. This polarization between the Democrats and Whigs dominated the Second Party System and laid the groundwork for the modern two-party structure. Jackson's leadership thus not only reshaped his own era but also established a political dynamic that would endure for generations.

Finally, Jackson's presidency and the rise of the Democratic Party reflected broader societal changes occurring in the early 19th century. The expansion of suffrage to include more white men, regardless of property ownership, mirrored the party's populist ethos. This democratization of politics, coupled with the party's emphasis on states' rights and limited government, appealed to a rapidly changing nation. The Democratic Party's emergence under Jackson's leadership was thus both a response to and a driver of the transformation of American society, ensuring its central role in the nation's political future.

Stronger Political Parties: Impact on Voter Turnout in Historical Context

You may want to see also

Whig Party Formation as opposition to Jackson's policies and centralization of power

The emergence of the Whig Party in the early 1830s was a direct response to President Andrew Jackson's policies and his centralization of power, marking a significant moment in the reappearance of political parties during his presidency. Jackson's tenure, often referred to as the era of "Jacksonian Democracy," was characterized by his assertive use of executive power, his opposition to elite institutions, and his support for the common man. However, his actions, particularly his handling of the Second Bank of the United States and his policies toward Native Americans, alienated a significant portion of the political elite and sparked organized opposition. This opposition coalesced into the Whig Party, which sought to counterbalance Jackson's dominance and what they perceived as his dangerous concentration of authority.

One of the primary catalysts for the formation of the Whig Party was Jackson's veto of the recharter of the Second Bank of the United States in 1832. The Bank, led by Nicholas Biddle, was seen by Jackson as a corrupt institution that favored the wealthy at the expense of the common people. His veto and subsequent removal of federal deposits from the Bank (known as the "Bank War") alarmed many politicians and businessmen who viewed the Bank as essential for economic stability. Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and other leaders who would later become key figures in the Whig Party, argued that Jackson's actions were an overreach of executive power and a threat to the constitutional balance of government. They believed that Jackson's policies undermined the rule of law and concentrated too much authority in the presidency, setting the stage for the Whigs to position themselves as defenders of limited government and federal institutions.

Another critical issue that fueled Whig opposition to Jackson was his policy of Indian removal, most notably exemplified by the forced relocation of Native American tribes along the "Trail of Tears." While Jackson justified these actions as necessary for westward expansion and national security, his opponents viewed them as morally reprehensible and unconstitutional. Whigs, who often aligned with evangelical and reform movements, criticized Jackson's disregard for Native American rights and the harsh enforcement of removal policies. This moral and constitutional critique further solidified the Whigs as a party opposed to Jackson's centralization of power and his disregard for checks and balances.

The Whigs also opposed Jackson's approach to states' rights and federal authority, particularly in the context of the Nullification Crisis of 1832-1833. While Jackson staunchly defended federal supremacy and threatened force against South Carolina for its attempt to nullify a federal tariff, Whigs like Clay sought a more conciliatory approach through compromise. The Whigs argued that Jackson's confrontational style and reliance on executive power risked national unity and constitutional order. This disagreement over the proper role of the federal government and the limits of presidential authority became a cornerstone of Whig ideology, distinguishing them from Jackson's Democratic Party.

Economically, the Whigs advocated for a more active federal role in promoting internal improvements, such as roads, canals, and railroads, which they believed would foster national growth and unity. This vision contrasted sharply with Jackson's skepticism of federal involvement in such projects, which he saw as unconstitutional and prone to corruption. The Whigs' emphasis on economic development and their support for a national bank reflected their broader opposition to Jackson's policies and their commitment to a more decentralized and institutionally balanced government. By framing themselves as the party of order, constitutionalism, and economic progress, the Whigs effectively mobilized opposition to Jackson's centralization of power and laid the groundwork for a new era of partisan politics.

In summary, the formation of the Whig Party was a direct and organized response to President Andrew Jackson's policies and his centralization of power. Through their opposition to his handling of the Second Bank of the United States, Indian removal, states' rights, and economic policies, the Whigs articulated a vision of government that emphasized checks and balances, federal institutions, and limited executive authority. Their emergence not only marked the reappearance of political parties during Jackson's presidency but also set the stage for a prolonged ideological struggle between Democrats and Whigs over the direction of American governance.

Switching Sides: Can Politicians Change Parties While in Office?

You may want to see also

Role of Spoils System in party loyalty and patronage during Jackson's presidency

The Spoils System, a hallmark of Andrew Jackson’s presidency, played a pivotal role in reshaping party loyalty and patronage during his administration. Jackson, a staunch advocate of democratic principles, believed in rotating federal officeholders to ensure that government positions reflected the will of the people. This system, often summarized by the phrase "to the victor belong the spoils," involved replacing incumbent federal employees with loyal supporters of the winning political party. By doing so, Jackson aimed to democratize the bureaucracy and reduce the influence of entrenched elites who had dominated government positions under previous administrations. This approach not only rewarded party loyalists but also solidified their commitment to Jackson’s Democratic Party, fostering a sense of unity and dependence on the party’s success.

The Spoils System directly contributed to the resurgence of political parties during Jackson’s presidency. As Jackson appointed thousands of his supporters to federal positions, these individuals became deeply invested in the party’s continued dominance to retain their jobs and influence. This patronage network created a robust infrastructure for the Democratic Party, ensuring that local and state-level party organizations remained active and loyal. In turn, these organizations mobilized voters, campaigned for Jacksonian candidates, and expanded the party’s reach across the nation. The system effectively tied the fortunes of individual officeholders to the party’s electoral success, making party loyalty a matter of personal and political survival.

Critics of the Spoils System argued that it prioritized political allegiance over competence, leading to inefficiency and corruption in government. However, from Jackson’s perspective, this was a small price to pay for breaking the stranglehold of a privileged few on federal offices. By distributing positions to a broader cross-section of society, Jackson sought to make the government more representative of the people it served. This approach resonated with the emerging democratic ideals of the time and helped solidify Jackson’s popularity among the common man. The Spoils System, therefore, became a tool not only for rewarding loyalty but also for legitimizing Jackson’s vision of a more inclusive and responsive government.

The Spoils System also had long-term implications for the structure and behavior of political parties. It institutionalized the practice of patronage as a central feature of American politics, a tradition that would persist well beyond Jackson’s presidency. Parties became more disciplined and organized, as they relied on patronage to maintain their power base. This dynamic encouraged the development of strong party machines, particularly in urban areas, where control over government jobs could translate into significant political influence. While the system had its drawbacks, it undeniably strengthened the Democratic Party and laid the groundwork for the modern two-party system in the United States.

In conclusion, the Spoils System was instrumental in fostering party loyalty and patronage during Andrew Jackson’s presidency. By rewarding supporters with government positions, Jackson not only solidified his political base but also revitalized the Democratic Party, ensuring its dominance in American politics. While the system faced criticism for its potential to undermine meritocracy, it achieved Jackson’s goal of making the government more accessible to the common people. The Spoils System’s legacy is evident in the enduring role of patronage in American politics and the resurgence of political parties as central actors in the democratic process.

Can Minors Join Political Parties? Exploring Youth Engagement in Politics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$41.8 $54.99

Sectionalism and Parties how regional interests influenced party realignment in the 1830s

The 1830s marked a significant period in American political history, characterized by the resurgence and realignment of political parties, heavily influenced by sectionalism and regional interests. When Andrew Jackson became president in 1829, the political landscape was in flux. The "Era of Good Feelings," which had seen a temporary decline in partisan politics, was giving way to new divisions. Jackson's presidency reignited partisan politics, but this time, the realignment was deeply rooted in regional differences, particularly between the North, South, and West. These regional interests shaped the emergence of new political parties, most notably the Democratic Party and the Whig Party, as they sought to represent distinct sectional agendas.

Sectionalism played a pivotal role in this realignment, as economic and social interests diverged across regions. The South, heavily dependent on agriculture and slavery, prioritized policies that protected their way of life, such as states' rights and the expansion of slavery into new territories. In contrast, the North, with its growing industrial economy, focused on tariffs, internal improvements, and economic modernization. The West, rapidly expanding through settlement and agriculture, sought federal support for infrastructure like roads and canals, as well as access to new lands. These competing interests created fissures that political parties exploited to gain support, leading to the formation of coalitions that reflected regional priorities.

The Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, appealed strongly to Western and Southern interests. Jackson's policies, such as his opposition to the Second Bank of the United States and his support for states' rights, resonated with farmers and planters who felt threatened by centralized financial institutions and federal overreach. His aggressive approach to Native American removal, particularly through the Indian Removal Act of 1830, also aligned with Western settlers' desires for expansion. Meanwhile, the South supported Jackson due to his defense of slavery and his willingness to challenge federal authority, as seen in the Nullification Crisis of 1832-1833.

In response to Jacksonian Democracy, the Whig Party emerged as a coalition of diverse interests, primarily from the North and parts of the South and West that opposed Jackson's policies. Whigs advocated for a strong federal government to promote economic development, including tariffs, internal improvements, and a national bank. Their support base included industrialists, merchants, and those who feared the concentration of power in the executive branch. While the Whigs were less unified than the Democrats, their regional appeal was clear: they drew support from areas that benefited from or sought federal intervention in economic matters.

The realignment of the 1830s was not merely a revival of political parties but a transformation driven by sectionalism. Regional interests dictated party platforms, alliances, and voter loyalties. The Democrats became the party of the "common man," particularly in the South and West, while the Whigs represented the interests of the emerging industrial North and those wary of Jackson's populism. This period underscored how deeply regional economic and social concerns could shape national politics, setting the stage for further sectional conflicts in the decades leading up to the Civil War. The reappearance and realignment of political parties during Jackson's presidency were thus inextricably linked to the sectional divisions of the time.

Can Political Parties Face Defamation Lawsuits? Legal Insights Explained

You may want to see also

Jackson's Populism appeal to common voters and its impact on party identity

Andrew Jackson's presidency marked a significant shift in American politics, particularly in the way political parties engaged with the electorate. His populist appeal to common voters not only redefined the political landscape but also played a pivotal role in the reemergence and transformation of political parties. Jackson's rhetoric and policies were deliberately crafted to resonate with the average American, positioning him as a champion of the common man against what he portrayed as an elitist establishment. This approach had a profound impact on party identity, as both the Democratic Party, which Jackson led, and its opponents were forced to adapt to the new political realities he created.

Jackson's populism was rooted in his portrayal of himself as an outsider fighting against the entrenched interests of the political and economic elite. He criticized institutions like the Second Bank of the United States, which he argued favored the wealthy at the expense of ordinary citizens. By vetoing the bank's recharter and framing his actions as a defense of the common people, Jackson solidified his image as a populist leader. This appeal to the masses mobilized previously disengaged voters, many of whom had felt alienated from the political process. As a result, the Democratic Party began to rebrand itself as the party of the common man, emphasizing themes of equality, opportunity, and resistance to privilege.

The impact of Jackson's populism on party identity was twofold. First, it democratized the political process by expanding the electorate. Jackson's administration supported the elimination of property requirements for voting, which had previously restricted suffrage to wealthier citizens. This broadening of the franchise not only increased voter participation but also compelled political parties to tailor their messages to a more diverse and less privileged audience. Second, Jackson's populism polarized the political landscape, as opponents of his policies coalesced into the Whig Party. The Whigs, while critical of Jackson's methods, were also influenced by his populist tactics, often framing their own policies as beneficial to the broader public rather than just the elite.

Jackson's emphasis on direct democracy and the will of the majority also reshaped how parties organized and operated. The Democratic Party, in particular, embraced a more grassroots approach, relying on mass rallies, parades, and local party organizations to mobilize voters. This shift marked a departure from the earlier, more elitist model of political parties, which had been dominated by congressional caucuses and state legislatures. By prioritizing the common voter, Jackson's populism forced parties to become more responsive to public opinion, a trend that would define American politics for decades to come.

In conclusion, Andrew Jackson's populist appeal to common voters was a transformative force in American political history. It not only revitalized political parties but also redefined their identities, making them more inclusive and responsive to the needs of the average citizen. The Democratic Party's embrace of populism and the Whig Party's emergence as a counterforce illustrate how Jackson's presidency reshaped the political landscape. His legacy underscores the enduring power of populist rhetoric in mobilizing voters and influencing party identity, a dynamic that continues to resonate in American politics today.

Did Patrick Leahy Switch Political Parties? Unraveling the Truth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, political parties reemerged during Andrew Jackson's presidency, with the Democratic Party supporting Jackson and the Whig Party forming in opposition to his policies.

Political parties reappeared due to divisions over Jackson's policies, such as his opposition to the Second Bank of the United States and his use of executive power, which polarized supporters and opponents.

The two main political parties that emerged were the Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, and the Whig Party, which formed in opposition to Jackson's policies and leadership style.