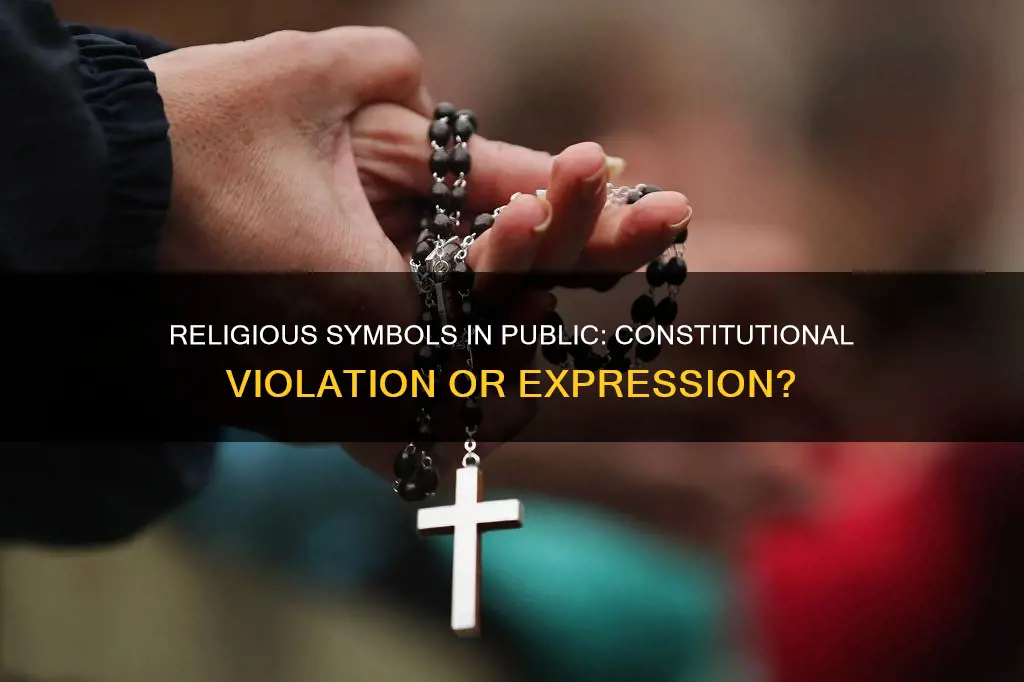

The display of religious symbols on public property is a contentious issue that has been the subject of much debate and legal scrutiny. The question of whether such displays violate the constitution, specifically the First Amendment's Establishment Clause, has been considered by the Supreme Court on several occasions, with rulings acknowledging the complexity and context-dependent nature of the matter. While the First Amendment protects the freedom of religious expression for individuals and private entities, the government's role in erecting, funding, and displaying religious symbols has been scrutinized to maintain religious neutrality and avoid endorsing specific faiths. The Supreme Court's rulings have considered various factors, including the historical context, the presence of secular symbols, and the overall effect of the display, to determine whether a violation of the Establishment Clause has occurred. The Court's decisions have significant implications for how different levels of government approach the inclusion of religious symbols in public spaces, shaping the relationship between church and state in the United States.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Display of religious symbols on public property | Does not violate the First Amendment non-establishment of religion clause if they are part of a larger display that includes secular symbols |

| Display of religious symbols on government property | Does not violate the Establishment Clause if the overall effect of the display is predominantly secular |

| Religious displays and monuments | The First Amendment protects the rights of houses of worship, homes, and businesses to display religious symbols openly and publicly |

| Religious displays on governmentally sponsored holiday displays | Varying results before the Court |

| Religious displays on publicly owned plazas | The Court ruled that the state could regulate the expressive content of speeches and displays only if the restriction was necessary and narrowly drawn to serve a compelling state interest |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Religious symbols on public property

The display of religious symbols on public property has been the subject of much debate and legal scrutiny, with the Supreme Court issuing several rulings on the matter. The First Amendment's establishment clause addresses Christian and other religious symbols on public land, and courts have ruled on the constitutionality of displaying such symbols.

In general, the display of religious symbols on public property does not violate the First Amendment's nonestablishment of religion clause as long as they are part of a larger display that includes secular symbols. For example, in 1984, the Supreme Court ruled that a city's inclusion of a nativity scene (creche) in an annual Christmas display on public property did not violate the establishment clause because it had a secular purpose and did not excessively entangle church and state. Similarly, in Lynch v. Donnelly (1984), the Court found that the inclusion of a Nativity scene in a city's Christmas display did not violate the Establishment Clause.

However, there have been cases where courts have concluded that the maintenance of certain religious symbols on public property constitutes an impermissible establishment of religion. For instance, in American Civil Liberties Union v. Rabun County Chamber of Commerce, Inc. (1982), the court ruled that a 22-story tall cross created by a state office building during the Christmas season violated the establishment clause.

The Supreme Court has also considered the constitutionality of religious symbols with historical significance, such as in American Legion v. American Humanist Association (2019), where the Court upheld the presence of a Latin Cross erected as a World War I memorial on public land. The Court reasoned that the memorial had acquired a significance that transcended its identity as a symbol of Christianity and that removing it would not be neutral with respect to religion.

The resulting establishment clause jurisprudence is fluid and highly dependent on the specifics of each case, but it offers essential insights into fundamental Constitutional tenets. The Supreme Court has strived to remain true to the goals of religious liberty intended by the Framers while assessing the constitutionality of religious symbols on public property.

The Affordable Care Act: Constitutional Conundrum?

You may want to see also

Religious neutrality

The concept of religious neutrality is a key aspect of the discussion surrounding public religious symbols and their potential violation of the constitution. Religious neutrality refers to the idea that the government should remain impartial and unbiased towards any particular religion or belief system. This principle is enshrined in the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, which prohibits the government from establishing or endorsing a specific religion.

In the context of public religious symbols, the question of religious neutrality is complex and has been the subject of numerous court cases. One notable example is the case of American Legion v. American Humanist Association, where the Supreme Court ruled that a 40-foot-tall Latin cross, known as the Bladensburg Cross, did not violate the Establishment Clause. The court considered the cross's history and its added secular meaning in the context of World War I memorials, concluding that its display was permissible. However, this decision has been criticised by some, including the ACLU, for undermining religious neutrality and sending a message of religious exclusion to non-Christian veterans.

Another case that highlights the complexity of religious neutrality is Lynch v. Donnelly (1984). In this case, the Supreme Court ruled that the inclusion of a Nativity scene (creche) in a city's Christmas display did not violate the Establishment Clause. The court applied the three-part Lemon test and concluded that the display had a secular purpose, did not primarily advance religion, and did not excessively entangle church and state. However, in a similar case, Allegheny County v. Greater Pittsburgh ACLU (1989), the inclusion of a creche in a holiday display was found to constitute a violation. These contrasting outcomes illustrate the challenges in determining whether public religious symbols uphold religious neutrality.

The definition of neutrality, as noted by the Rehnquist Court, depends largely on perception. If government funding or involvement with religious expression appears secondary or indirect, it is more likely to be viewed as neutral and not a violation of church-state separation. This perception of neutrality was also considered in the case of Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, where the Court upheld Ohio's private school voucher program, which included religious schools.

In addition to these cases, the Supreme Court has also addressed the constitutionality of religious symbols on public property, such as the Ten Commandments monument displayed in a Utah public park. While some justices considered the monument's presence among other secular displays as a factor in determining neutrality, others emphasised the importance of context and the government's intent in conveying a message of religious favouritism.

Overall, the principle of religious neutrality is central to the debate surrounding public religious symbols and the interpretation of the Establishment Clause. While there have been varying rulings on the constitutionality of specific displays, the courts generally aim to ensure that the government does not endorse or favour any particular religion, maintaining a neutral stance in matters of religion.

Patrick Henry's Constitutional Opposition: Valid Argument?

You may want to see also

The Lemon test

The three parts of the test are as follows:

- Secular Purpose: The court examines the proposed aid to the religious entity and ensures that it has a clear secular purpose.

- Secular Effect: The court determines if the primary effect of the aid is to advance or inhibit religion.

- Excessive Entanglement: The court examines whether the aid would create an excessive entanglement between the government and religion.

Texas Constitution of 1836: Legalizing Slavery?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The Establishment Clause

The Supreme Court has also considered the constitutionality of religious symbols in other contexts, such as legislative sessions, public school education, and public funding for religious activities.

James Madison's Constitution: Amendments and the Bill of Rights

You may want to see also

Religious liberty

The display of religious symbols on public property has been the subject of debate and legal rulings. The Supreme Court has issued several decisions addressing the constitutionality of such displays. For example, in 1984, the Court ruled that including a nativity scene as part of a larger Christmas display on public property did not violate the Establishment Clause. The Court applied the Lemon test, concluding that the display had a secular purpose, did not primarily advance religion, and did not excessively entangle church and state.

However, in another case, the Supreme Court ruled that a nativity creche had to be removed, while a Chanukah menorah was permitted. The Court emphasised that the constitution prohibits any governmental "endorsement" of religion and that religious displays must be considered in their specific context.

In recent years, the Supreme Court has allowed more religious symbols on public property, particularly long-standing monuments. In 2019, the Court upheld the presence of a Latin Cross erected as a World War I memorial, citing its historical importance and the fact that it had stood undisturbed for nearly a century. The Court's decision was based on the principle of respecting and tolerating religious diversity, as enshrined in the First Amendment.

The question of whether religious practices that conflict with secular law should be permitted due to religious freedom is a complex one, addressed in various court cases, including Reynolds v. United States and Wisconsin v. Yoder in the US, and S.A.S. v. France in Europe. The concept of religious liberty is a cornerstone of American democracy, and the ongoing legal debates and rulings surrounding it reflect the dynamic nature of this fundamental right.

Defending the Constitution: A Citizen's Right and Duty

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The display of religious symbols on public property does not violate the constitution as long as they are part of a larger display that includes secular symbols. The Supreme Court has ruled that a city’s practice of including a nativity scene in a Christmas display on public property did not violate the establishment clause as it was accompanied by secular objects like a Santa Claus house and reindeer.

The Lemon test is a standard used to apply the First Amendment’s ban on government “establishment of religion”. A government activity is judged invalid if its purpose was religious in nature, if its main effect is to promote or interfere with religion, or if it “excessively entangles” government in religious affairs.

In American Legion v. American Humanist Association (2019), the Supreme Court reviewed a Latin Cross erected as a World War I memorial on public land. The Court upheld the memorial, citing its historical importance and the fact that it had stood undisturbed for nearly a century. In Lynch v. Donnelly (1984), the Court ruled that the inclusion of a nativity scene in a city's Christmas display did not violate the establishment clause.