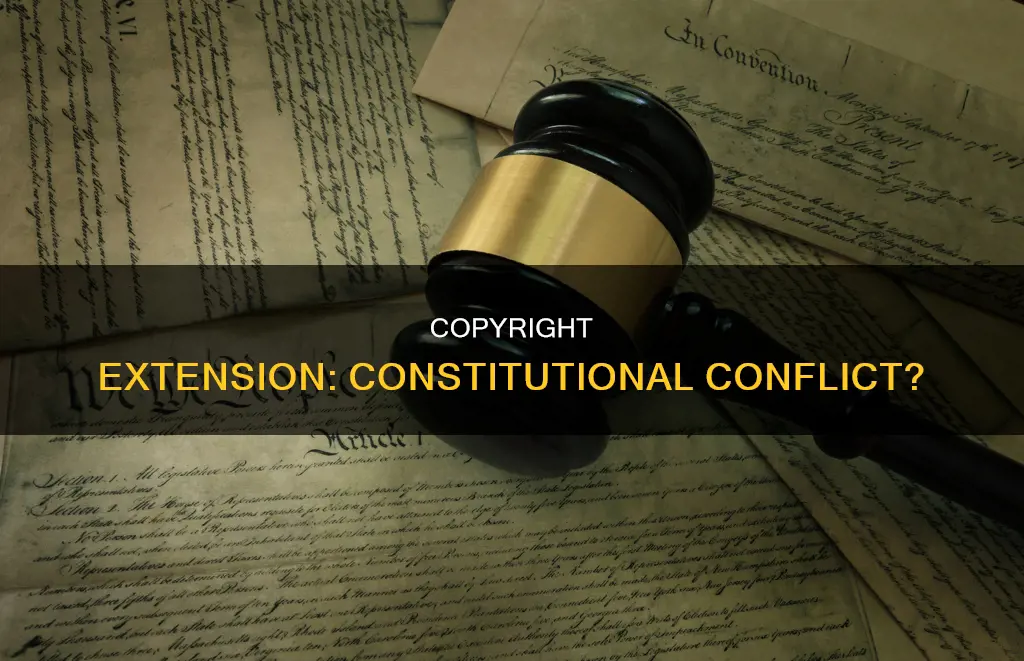

The question of whether extended copyright protection conflicts with the constitution has been the subject of debate in the United States. Opponents of extended copyright protection, such as archivists, scholars, and internet publishers, have argued that it impedes free speech and stifles creativity. They contend that Congress has exceeded the Constitutional directive that copyright protection be for limited times. On the other hand, supporters of extended copyright protection, including publishers, film producers, artists, authors, musicians, and their heirs, argue that it provides an incentive to create and disseminate derivative works. In 2003, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that extended copyright protection, specifically the 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA), was not in violation of the U.S. Constitution.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA) | Valid law |

| CTEA supporters | Publishers, film producers, artists, authors, musicians, their heirs, corporate copyright owners, Time Warner, Universal, Viacom, ASCAP, major professional sports leagues (NFL, NBA, NHL, MLB), the family of slain singer Selena Quintanilla-Pérez |

| CTEA opponents | Archivists, scholars, internet publishers, opponents of the Bono Act |

| CTEA opponents' arguments | Congress exceeded the Constitutional directive that copyright protection be for "limited times"; CTEA violated the First Amendment right of free speech; CTEA impeded free speech and stifled creativity; CTEA improperly stretched the duration of copyright protection so as to be virtually perpetual |

| CTEA supporters' arguments | The Constitution "gives Congress wide leeway"; Congress acted within its authority; CTEA "is a rational enactment"; CTEA would provide an incentive to disseminate derivative works; CTEA does not interfere with free speech under the First Amendment; Copyright Act already contains provisions to ensure freedom of speech |

| Court ruling | The U.S. Supreme Court ruled on January 15, 2003 that the CTEA was not in violation of the U.S. Constitution |

| Copyright protection | Does not extend to any idea, procedure, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery |

| Copyright protection balance | Doctrine of fair use |

Explore related products

$5.74 $9.99

What You'll Learn

The 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA)

Opponents of the CTEA argued that the act impeded free speech and stifled creativity. They pointed to the Copyright Clause of the Constitution, which sets forth the goal of providing an incentive to authors by allowing them exclusive rights in their works. They argued that because the CTEA applied to existing works as well as future works, there could be no incentive to create regarding works already created. They also asserted that Congress had improperly stretched the duration of copyright protection so as to be virtually perpetual.

The Supreme Court, by a vote of 7 to 2, rejected the opponents' arguments, deferring to Congress and upholding the CTEA. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, writing for the majority, found that the Constitution "gives Congress wide leeway" and that "Congress acted within its authority". She also noted that the CTEA would provide an incentive to disseminate derivative works. The Court also rejected the argument that the CTEA interfered with free speech under the First Amendment, explaining that the Copyright Act already contains provisions to ensure freedom of speech.

Understanding Constitutional Protections for Illegal Immigrants in America

You may want to see also

The CTEA's violation of the First Amendment right to free speech

Opponents of the 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA) argue that it violates the First Amendment right to free speech. They claim that the CTEA impedes free speech and stifles creativity, as it applies to existing works as well as future works, meaning there is no incentive to create new works. They also argue that Congress has improperly stretched the duration of copyright protection to be virtually perpetual, exceeding the Constitutional directive that copyright protection be for "limited times".

However, in Eldred v. Ashcroft, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on January 15, 2003, that the CTEA was not in violation of the U.S. Constitution. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, writing for the majority, found that the Constitution "gives Congress wide leeway" and that "Congress acted within its authority". She also observed that the CTEA would provide an incentive to disseminate derivative works and that all prior extensions had also applied to pre-existing works. The Court rejected the argument that the CTEA interfered with free speech under the First Amendment, noting that the Copyright Act already contains provisions to ensure freedom of speech.

It is important to note that copyright protection does not extend to any idea, procedure, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery. The doctrine of fair use provides a balance between copyright protection and free speech concerns.

US Nationals: What Protections Does the Constitution Guarantee?

You may want to see also

The CTEA's stifling of creativity

Opponents of the 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA) argue that it stifles creativity by removing the incentive to create new works. The CTEA applies to both existing and future works, meaning that there is no incentive to create new works based on works that have already been created. This, they argue, means that the CTEA stifles creativity.

They also argue that the CTEA interferes with free speech under the First Amendment. However, the Supreme Court rejected this argument, noting that the Copyright Act already contains provisions to ensure freedom of speech.

In Eldred v. Ashcroft, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on January 15, 2003 that the CTEA was not in violation of the U.S. Constitution. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, writing for the majority, found that the Constitution gives Congress wide leeway and that Congress acted within its authority. She also observed that the CTEA would provide an incentive to disseminate derivative works.

The CTEA has been supported by publishers, film producers, artists, authors, musicians and their heirs, as well as corporate owners of copyrights.

US Territories: Constitutional Protections for People?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The CTEA's application to existing works

Opponents of the 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA) argue that it impedes free speech and stifles creativity. They claim that because the CTEA applies to existing works, there can be no incentive to create regarding works that have already been created.

The CTEA, also known as the Sonny Bono Copyright Extension Act, was passed to extend the duration of copyright protection. Sonny Bono wanted the term of copyright protection to last forever, but this would have violated the Constitution. Instead, the CTEA was passed to extend the duration of copyright protection for existing works as well as future works.

The Supreme Court, by a vote of 7 to 2, rejected the opponents' arguments and upheld the CTEA. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, writing for the majority, found that the Constitution "gives Congress wide leeway" and that "Congress acted within its authority". She also noted that the CTEA would provide an incentive to disseminate derivative works and that all prior extensions had also applied to pre-existing works.

The CTEA has been applauded by publishers, film producers, artists, authors, musicians, and their heirs, as well as corporate owners of copyrights. They argue that the CTEA provides an incentive to authors by allowing them exclusive rights in their works.

Framers' Constitution: Protecting Slavery and its Legacy

You may want to see also

The CTEA's interference with the Copyright Clause of the Constitution

Opponents of the 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA) argue that it interferes with the Copyright Clause of the Constitution. The CTEA, also known as the Sonny Bono Copyright Extension Act, applies to existing works as well as future works. Opponents argue that this means there is no incentive to create new works, as the CTEA applies to works already created. They also argue that Congress has improperly stretched the duration of copyright protection so that it is virtually perpetual.

Supporters of the CTEA, including publishers, film producers, artists, authors, musicians, and their heirs, as well as corporate owners of copyrights, argue that the CTEA is a valid law. They believe that the CTEA provides an incentive to disseminate derivative works.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled on January 15, 2003, that the CTEA was not in violation of the U.S. Constitution. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, writing for the majority, found that the Constitution "gives Congress wide leeway" and that "Congress acted within its authority". She also observed that the CTEA would provide an incentive to disseminate derivative works and that all prior extensions had also applied to pre-existing works. The Court rejected the argument that the CTEA interfered with free speech under the First Amendment, noting that the Copyright Act already contains provisions to ensure freedom of speech.

The US Constitution: Protecting Citizens or the Powerful?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on January 15, 2003 that the 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA) was not in violation of the U.S. Constitution.

Opponents argued that the act impeded free speech and stifled creativity. They also asserted that Congress had improperly stretched the duration of copyright protection so as to be virtually perpetual.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, writing for the majority, found that the Constitution "gives Congress wide leeway" and that "Congress acted within its authority". She also observed that the CTEA would provide an incentive to disseminate derivative works.

![A General View of the United States of America. With an Appendix Containing the Constitution. The Tariff of Duties. The Laws of Patents and Copyrights, &C. 1833 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)