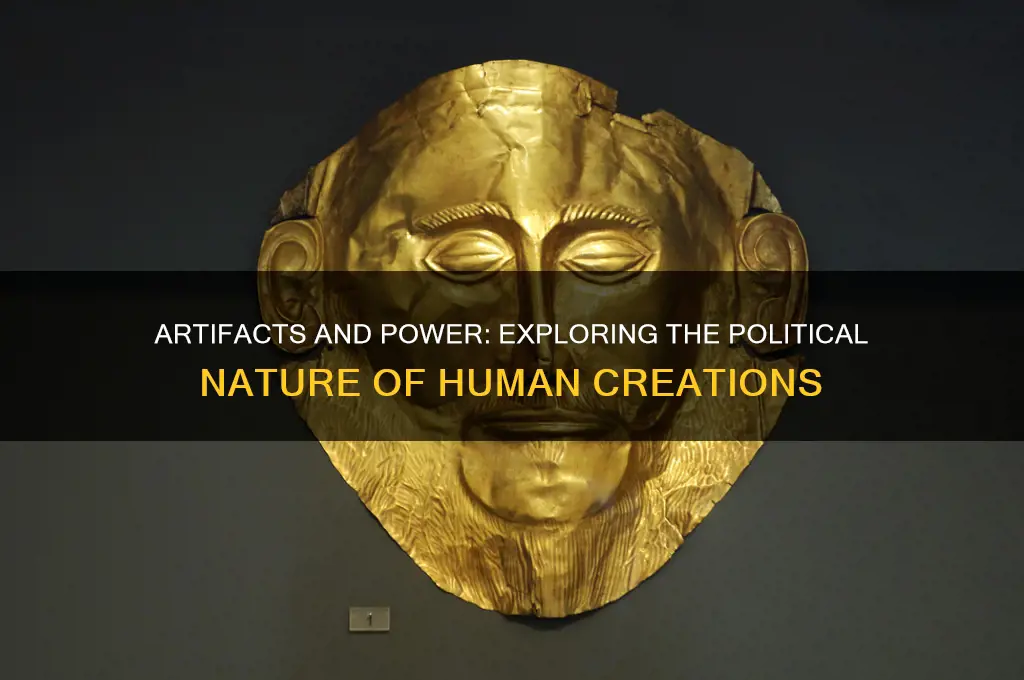

The essay Do Artifacts Have Politics? by Langdon Winner explores the intriguing idea that technological objects and systems are not neutral tools but embody inherent political values and ideologies. Winner argues that the design, implementation, and impact of artifacts—ranging from bridges and highways to software and algorithms—reflect and reinforce specific social and political agendas. By examining how these technologies shape human behavior, distribute power, and influence societal structures, the essay challenges readers to reconsider the relationship between technology and politics, suggesting that even the most mundane artifacts can carry significant political implications. This thought-provoking perspective invites a deeper analysis of how technology is created, deployed, and experienced in our daily lives.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Author | Langdon Winner |

| Title | Do Artifacts Have Politics? |

| Publication Year | 1980 |

| Main Argument | Technological artifacts embody specific forms of power and political values, shaping social relations and behaviors. |

| Key Concepts | - Inherent Politics: Artifacts can have political implications regardless of their creators' intentions. - Technological Determinism: Critique of the idea that technology is neutral. - Design Choices: The design of artifacts reflects societal values and power structures. |

| Examples | - Robert Moses' Bridges: Low clearance bridges in New York that prevented buses (used by poorer communities) from accessing parks. - Atomic Bomb: A technology with inherently political and destructive consequences. |

| Influence | Pioneering work in the field of Science and Technology Studies (STS), influencing discussions on technology ethics, design, and societal impact. |

| Criticism | Some argue that attributing politics to artifacts oversimplifies complex social dynamics and human agency. |

| Relevance Today | Highly relevant in debates about AI, surveillance technologies, and the ethical design of digital platforms. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Design reflects values: Artifacts embody societal norms, biases, and power structures through their design choices

- Technology as ideology: Tools and systems often promote specific political or economic ideologies

- Accessibility and exclusion: Artifacts can either democratize or limit access based on design decisions

- Environmental impact: The politics of resource use, waste, and sustainability in artifact production

- Control and surveillance: How artifacts enable monitoring, shaping behavior, and exerting power over users

Design reflects values: Artifacts embody societal norms, biases, and power structures through their design choices

The design of everyday objects is never neutral. Consider the height of a doorknob. Placed at 36 inches, it accommodates the average adult but excludes children and wheelchair users. This seemingly mundane decision encodes assumptions about who belongs in a space and who does not. It prioritizes convenience for a specific demographic while marginalizing others, demonstrating how design choices silently reinforce social hierarchies.

Every artifact, from the layout of a city to the interface of a smartphone, carries within it the values and biases of its creators. These choices are not accidental; they are deliberate reflections of the societal norms and power structures that shape our world.

Take the example of urban planning. Grid systems, prevalent in American cities, prioritize efficiency and individual mobility, often at the expense of community spaces and pedestrian accessibility. In contrast, European cities with winding streets and public squares prioritize social interaction and a more human-centered experience. These design philosophies reflect differing cultural values: one emphasizing individualism and progress, the other community and tradition. The very layout of our cities, therefore, becomes a physical manifestation of our collective priorities.

Even the seemingly innocuous design of a coffee mug can reveal hidden biases. A handle designed for a right-handed grip excludes left-handed users, subtly reinforcing a right-handed norm. This example highlights how design choices, often made without conscious malice, can perpetuate exclusion and inequality.

To understand the political nature of design, we must analyze the "who" behind the decisions. Who decides what is "user-friendly"? Whose needs are prioritized? Whose voices are excluded from the design process? By asking these questions, we can begin to dismantle the invisibility of power structures embedded within our everyday objects.

A critical approach to design involves actively seeking out and amplifying marginalized perspectives. This means involving diverse users in the design process, challenging established norms, and prioritizing inclusivity over convenience.

Ultimately, recognizing the political nature of design empowers us to become more conscious consumers and creators. We can choose to support products and systems that reflect our values of equity and inclusivity. We can advocate for design practices that prioritize the needs of all users, not just the dominant group. By doing so, we can begin to reshape our material world into one that truly reflects the diversity and complexity of human experience.

Eco-Friendly Campaign Cleanup: Recycling Political Signs After Elections

You may want to see also

Technology as ideology: Tools and systems often promote specific political or economic ideologies

The design of a city’s transportation system is never neutral. Consider the grid layout of Manhattan versus the sprawling highways of Los Angeles. The former encourages public transit and pedestrian movement, fostering a denser, more communal urban life. The latter prioritizes individual car ownership, reinforcing suburban sprawl and economic segregation. These systems don’t merely facilitate movement—they embed values about autonomy, equality, and resource distribution. A bus lane or a bike-sharing program isn’t just infrastructure; it’s a policy statement about who deserves access to space and mobility.

To illustrate further, examine the smartphone. Its design—from the App Store’s curated ecosystem to the preinstalled software—reflects a market-driven ideology. Apple’s closed system promotes control and monetization, while Android’s openness aligns with a more decentralized, developer-friendly ethos. Even the absence of a headphone jack or the inclusion of facial recognition technology carries ideological weight, prioritizing corporate profit or surveillance capabilities over user autonomy. These choices aren't accidental; they’re deliberate, shaping behavior and reinforcing specific economic models.

Here’s a practical exercise: Analyze the user interface of a digital payment app. Notice how it nudges you toward certain behaviors—like tipping, rounding up for charity, or subscribing to premium services. These design elements aren’t just functional; they’re ideological, promoting consumerism, altruism, or loyalty within a capitalist framework. To counter this, consider using open-source alternatives or apps that prioritize privacy, such as Signal or ProtonMail. These tools embody a different ideology—one that values user sovereignty over corporate control.

A cautionary tale comes from the history of the QWERTY keyboard. Originally designed to slow down typists and prevent typewriter jams, it persists today not because it’s efficient, but because it’s entrenched. This example highlights how technological standards can lock in outdated ideologies, stifling innovation and perpetuating inefficiencies. Similarly, the dominance of proprietary software over open-source alternatives isn’t just a market outcome—it’s a political choice that favors monopolies over collaboration.

In conclusion, every tool and system carries the imprint of its creators’ beliefs. To navigate this, adopt a critical lens: Ask who benefits from a technology’s design, whose needs it ignores, and what alternatives exist. By doing so, you can recognize—and resist—the ideologies embedded in the artifacts you use daily. Technology isn’t just a tool; it’s a battleground for values.

Romanticism's Political Impact: Shaping Nations and Challenging Authority

You may want to see also

Accessibility and exclusion: Artifacts can either democratize or limit access based on design decisions

The design of a staircase, seemingly mundane, embodies a political choice. Wide, shallow steps with railings cater to all ages and abilities, inviting universal access. Narrow, steep flights without support, however, exclude those with mobility challenges, silently reinforcing social hierarchies. This example illustrates how artifacts, through design decisions, can either democratize or restrict participation in physical spaces.

Consider the smartphone. Its touchscreen interface, intuitive for many, presents a barrier for individuals with visual impairments. Voice assistants, while helpful, often fall short in accuracy and functionality. The absence of haptic feedback or alternative input methods limits access to information, communication, and services for a significant portion of the population. This exclusion isn't inherent to the technology itself, but a consequence of design choices that prioritize certain user profiles over others.

The impact of these choices extends beyond physical limitations. Language settings, for instance, determine who can effectively utilize a device or platform. A website available only in English excludes non-English speakers, perpetuating linguistic inequality. Similarly, the cost of technology acts as a powerful gatekeeper. Expensive smartphones or software subscriptions create a digital divide, privileging those with financial means and marginalizing others.

These examples highlight a crucial point: accessibility isn't an afterthought, but a fundamental design principle. It requires conscious effort to anticipate diverse needs and incorporate inclusive features from the outset. This involves considering factors like:

- Physical abilities: Incorporating features like adjustable font sizes, color contrast options, and alternative input methods.

- Sensory abilities: Providing text alternatives for images, captions for videos, and clear audio descriptions.

- Cognitive abilities: Using plain language, clear navigation, and consistent design elements.

- Economic accessibility: Offering affordable options, free trials, or subsidized access for underserved communities.

By embracing these principles, designers can create artifacts that empower rather than exclude, fostering a more equitable and inclusive world. The politics of design are not neutral; they shape who participates, who benefits, and who is left behind. Choosing accessibility is a political act, a commitment to building a society where everyone has the opportunity to engage and thrive.

Are BLM Signs Political? Exploring the Intersection of Activism and Expression

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental impact: The politics of resource use, waste, and sustainability in artifact production

Artifacts, from smartphones to skyscrapers, are not politically neutral. Their creation, use, and disposal are deeply entangled in resource extraction, environmental degradation, and power dynamics. Consider the rare earth minerals in your phone: their mining often occurs in regions with lax environmental regulations, displacing communities and poisoning ecosystems. This is not a byproduct of production; it is a deliberate choice, a political act that prioritizes profit over planetary health.

Every artifact carries an ecological footprint, a silent ledger of resource depletion and waste generation. The fashion industry, for instance, consumes 93 billion cubic meters of water annually, enough to meet the needs of 110 million people. Fast fashion’s relentless cycle of production and disposal exemplifies how artifacts are designed not for longevity but for obsolescence, fueling a system that thrives on excess and discards the Earth as collateral damage.

To mitigate this, adopt a lifecycle mindset. Before purchasing, ask: Can this be repaired? Is it made from recycled materials? Does the company prioritize sustainable practices? Opt for secondhand goods, support local artisans, and advocate for policies that incentivize circular economies. Remember, every choice is a vote for the kind of world you want to inhabit.

Compare the environmental impact of a plastic water bottle to a reusable stainless steel one. The former, designed for single use, contributes to the 8 million metric tons of plastic entering oceans annually. The latter, while requiring more energy to produce, lasts for years, reducing waste and resource demand. This comparison highlights how design decisions—driven by corporate interests and consumer demand—shape environmental outcomes.

Finally, sustainability is not just a technical challenge but a political one. Governments must regulate industries to curb pollution and resource exploitation, while corporations must be held accountable for their ecological footprints. As consumers, we wield power through our choices, but systemic change requires collective action. Artifacts may seem apolitical, but their environmental impact is a stark reminder that every object tells a story of power, profit, and the planet’s precarious future.

Rising Influence: Gauging the Popularity of New Politics Today

You may want to see also

Control and surveillance: How artifacts enable monitoring, shaping behavior, and exerting power over users

Artifacts, from the design of urban spaces to the algorithms of social media platforms, are not neutral tools but active agents in the exercise of control and surveillance. Consider the ubiquitous CCTV camera, a seemingly passive observer that, in reality, reshapes public behavior by instilling a sense of being watched. Its presence alone alters how individuals move, interact, and even think in public spaces, demonstrating how artifacts can enforce norms without explicit coercion. This silent governance is a testament to the political nature of design, where the very structure of an object dictates its power over users.

To understand this dynamic, examine the architecture of panopticon prisons, a design where a central guard tower allows for the constant surveillance of inmates without them knowing when they are being observed. This model has been replicated in modern workplaces through open-plan offices and digital monitoring tools like keystroke trackers. The effect is twofold: it increases productivity by fostering self-regulation and consolidates power in the hands of employers. Artifacts here are not just tools for efficiency but instruments of behavioral conditioning, subtly reinforcing hierarchies and compliance.

A persuasive argument can be made for the ethical implications of such designs. Take smart home devices, for instance, which collect data on user habits under the guise of convenience. While users enjoy personalized experiences, they often overlook the extent to which their data is commodified and used to predict and manipulate future behavior. This trade-off between utility and privacy highlights the insidious nature of surveillance artifacts, which often cloak their political agendas in the promise of progress and ease.

Comparatively, the design of public transportation systems offers a more benign but equally instructive example. Turnstiles and automated ticketing systems not only manage passenger flow but also monitor movement patterns, ensuring compliance with fare regulations. While these artifacts serve a practical purpose, they also embed a form of social control, delineating who can access certain spaces and under what conditions. This duality underscores how even mundane artifacts can embody and enforce political ideologies.

In practice, individuals can mitigate the impact of surveillance artifacts by adopting specific strategies. For instance, using privacy-focused browsers, disabling non-essential smart device features, and advocating for transparent data policies can reclaim some autonomy. However, these measures are reactive, addressing symptoms rather than the root cause. The true challenge lies in reimagining design itself—prioritizing user agency over control, and embedding ethical considerations into the creation of artifacts. Only then can we hope to dismantle the invisible architectures of power that shape our lives.

Are Asian Americans Politically Oppressed? Exploring Systemic Barriers and Representation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The essay argues that technological artifacts, such as bridges or nuclear power plants, embody political values and ideologies, reflecting the priorities and biases of their creators and societies.

The essay was written by Langdon Winner, a philosopher of technology, and was first published in 1980.

Winner discusses the low clearance of underpasses on Long Island parkways, designed by Robert Moses, which prevented buses (often used by poorer or minority communities) from accessing certain areas, thus embedding social control into infrastructure.

The essay challenges the notion that technology is neutral by demonstrating how artifacts are shaped by human intentions, societal values, and power structures, making them inherently political.