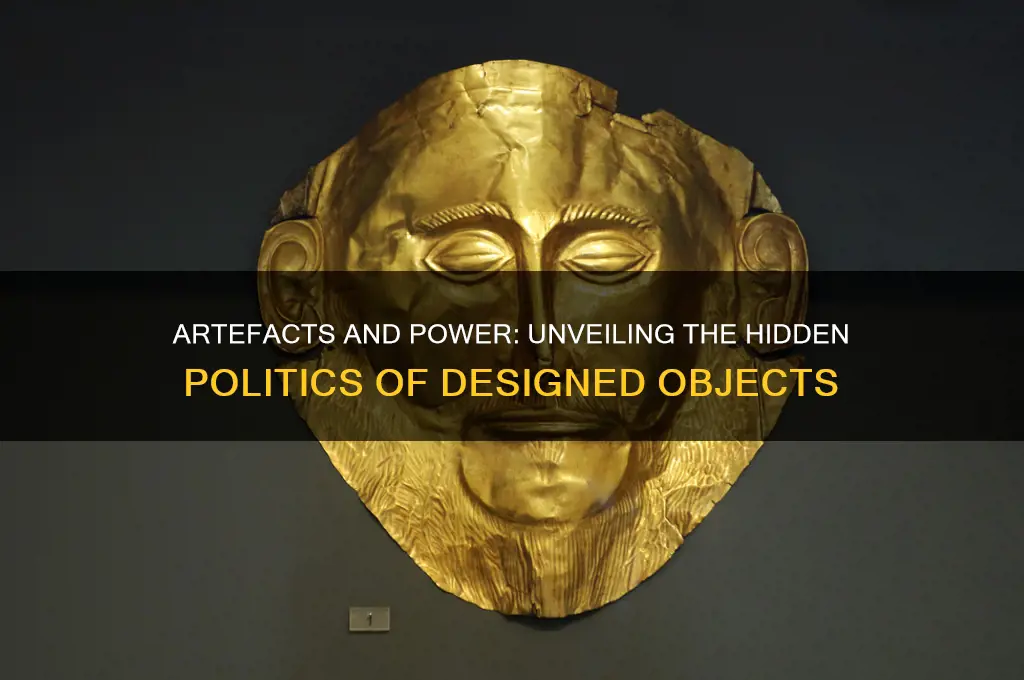

The question Do artefacts have politics? challenges us to consider whether the design, function, and impact of human-made objects are inherently neutral or if they carry embedded values, biases, and power structures. Coined by Langdon Winner in his influential essay, this inquiry highlights how artefacts—from bridges and highways to software and algorithms—can reinforce or challenge social hierarchies, influence behavior, and shape societal norms. By examining the intentional and unintentional consequences of technological and material creations, we are prompted to recognize that artefacts are not merely tools but active participants in the political and cultural landscapes they inhabit. This perspective invites a critical reevaluation of how we design, use, and interact with the objects that define our world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Intentional Design | Artifacts are designed with specific purposes, reflecting the intentions and values of their creators. |

| Embedded Values | They embody the social, cultural, and political values of the context in which they were created. |

| Shaping Behavior | Artifacts influence user behavior by guiding, constraining, or enabling certain actions. |

| Power Dynamics | They can reinforce or challenge existing power structures, often favoring certain groups over others. |

| Normative Influence | Artifacts promote specific norms and practices, shaping societal expectations. |

| Invisibility of Politics | The political nature of artifacts is often hidden or taken for granted, appearing neutral. |

| Scalability | Their impact scales with widespread adoption, amplifying their political effects. |

| Historical Context | Artifacts are products of their time, reflecting historical and ideological contexts. |

| Resistance and Adaptation | Users may resist, adapt, or repurpose artifacts, altering their intended political effects. |

| Interconnectedness | Artifacts are part of larger systems, interacting with other technologies and societal structures. |

Explore related products

$25 $25

$40.6 $56.99

What You'll Learn

- Design embeds values: Artefacts reflect creators' beliefs, shaping user behavior and societal norms

- Technological determinism: Tools influence culture, limiting or enabling human actions and choices

- Bias in technology: Artefacts can perpetuate inequality through discriminatory design or access

- Political symbolism: Objects often represent power, ideology, or resistance in societies

- Environmental impact: Artefacts' production and use reflect political choices about sustainability

Design embeds values: Artefacts reflect creators' beliefs, shaping user behavior and societal norms

Design is never neutral. Every artefact, from the smartphone in your pocket to the bench in your local park, carries the imprint of its creator’s values, assumptions, and biases. Consider the curved edges of an iPhone, which subtly encourage single-handed use, or the height of a water fountain, designed for adults but often inaccessible to children. These choices aren’t accidental—they reflect decisions about who matters, how they should interact with the world, and what behaviors are desirable. When designers prioritize sleekness over repairability, they embed a throwaway culture into the product. When they default to male measurements for ergonomic tools, they reinforce gendered assumptions about who uses them. Artefacts don’t just serve functions; they teach us how to live, often without our noticing.

To illustrate, examine the design of urban public spaces. A park with wide, open lawns and sparse seating suggests a preference for passive recreation over social gathering. Conversely, a plaza filled with movable chairs and tables invites flexibility and community interaction. These layouts aren’t politically neutral. They shape who feels welcome, how people behave, and even what kinds of social relationships are possible. For instance, a study of New York City’s High Line found that its narrow pathways and fixed seating discouraged large groups, effectively curating a certain type of visitor. Designers, whether consciously or not, act as policymakers, using form and function to enforce unspoken rules about public life.

If you’re a designer, here’s a practical tip: interrogate your defaults. Ask yourself whose needs your artefact prioritizes and whose it ignores. For example, if you’re creating a fitness app, ensure it accommodates diverse age groups by including low-impact exercises for seniors and scalable intensity levels for younger users. Similarly, if you’re designing a public restroom, consider gender-neutral options to support inclusivity. A simple rule of thumb: if your design assumes a "typical user," challenge that assumption. Incorporate feedback from marginalized groups early in the process, and test your prototypes with a wide range of users. This isn’t just ethical—it’s good design, because it creates artefacts that serve more people, more effectively.

The societal impact of value-laden design extends beyond individual products. Take the QWERTY keyboard, originally designed to slow down typists and prevent typewriter jams. This layout persists today, not because it’s optimal, but because it’s entrenched. It’s a reminder that once a design becomes widespread, it can shape norms for generations. Similarly, the layout of suburban neighborhoods, with their reliance on cars, reflects mid-20th-century values of individualism and mobility. These designs don’t just reflect the past—they actively resist change, making it harder to adopt public transit or walkable communities. To counter this, designers must think not just about the artefact’s immediate purpose, but its long-term effects on behavior and culture.

Finally, consider the power dynamics at play. Artefacts often amplify the values of those with the most influence, marginalizing others in the process. For instance, voice recognition software historically struggled with non-native English accents, effectively excluding millions of users. This isn’t a technical limitation—it’s a reflection of whose voices were prioritized during development. To avoid this, adopt a "design justice" approach: center the needs of the most vulnerable users, not just the majority. Start by mapping out how your artefact could be misused or exclude certain groups, then redesign to mitigate those risks. By doing so, you’re not just creating a tool—you’re shaping a more equitable world.

Are You Politically Exposed? Understanding Risks and Compliance Essentials

You may want to see also

Technological determinism: Tools influence culture, limiting or enabling human actions and choices

The hammer, a seemingly neutral tool, embodies technological determinism. Its design dictates a specific grip, swing, and purpose. This physical form limits its use to driving nails, shaping metal, or breaking objects. A culture without hammers would lack the ability to construct wooden structures with the same efficiency, illustrating how tools shape the very possibilities of human action.

Imagine a society where the primary tool for shaping materials was a chisel. Architecture would prioritize stone and intricate carvings, not the rapid assembly of timber frames. This example highlights how tools, through their inherent design, guide cultural development by enabling certain practices while rendering others impractical.

Consider the internet, a tool with far-reaching consequences. Its architecture, built on interconnected networks, fosters global communication and information sharing. However, this design also enables the spread of misinformation and facilitates surveillance. The internet's structure doesn't inherently promote democracy or authoritarianism, but it creates a landscape where both can flourish, demonstrating how tools provide both opportunities and constraints.

The internet's impact on political discourse is a prime example. Social media platforms, designed for engagement and virality, often prioritize sensational content over nuanced debate. This design feature can limit the quality of public discourse, shaping political conversations in ways that favor emotional appeals over reasoned argumentation.

Technological determinism isn't about inevitability. We can consciously design tools that mitigate negative consequences. For instance, social media platforms could implement algorithms that prioritize factual information and diverse viewpoints. Similarly, urban planners can design cities that encourage walking and cycling, reducing reliance on cars and promoting healthier lifestyles. Recognizing the inherent politics of tools empowers us to shape technology in ways that align with our values and aspirations.

Understanding the Rationalizations Behind Political Violence in America

You may want to see also

Bias in technology: Artefacts can perpetuate inequality through discriminatory design or access

Technology is not neutral. Every algorithm, interface, and device carries the biases of its creators, whether intentional or not. Facial recognition systems, for instance, have been shown to misidentify people of color at rates up to 100 times higher than white individuals. This isn’t a bug—it’s a reflection of the datasets used to train these systems, which often underrepresent diverse populations. When such tools are deployed in law enforcement or hiring processes, the result is systemic discrimination baked into the very fabric of our digital infrastructure.

Consider the design of voice assistants like Siri or Alexa, which default to female voices in most languages. This perpetuates the stereotype of women as subservient helpers, reinforcing gender roles in subtle yet pervasive ways. Even the language models powering these assistants often struggle with non-binary pronouns or dialects outside standard English, marginalizing already underrepresented communities. These design choices aren’t accidental; they stem from a lack of diversity in tech teams and a failure to critically examine the societal implications of their work.

Access to technology further exacerbates inequality. In the U.S., 17% of rural households lack broadband internet, compared to just 1% in urban areas. This digital divide limits educational opportunities, job prospects, and access to healthcare for millions. Meanwhile, smartphones, often marketed as universal tools, are priced out of reach for many low-income individuals globally. Without equitable access, technology becomes a privilege rather than a right, widening the gap between the haves and have-nots.

To address these issues, designers and engineers must adopt a framework of inclusive design. Start by diversifying teams to ensure a range of perspectives. Conduct bias audits on algorithms and datasets, prioritizing transparency and accountability. For example, the EU’s AI Act mandates risk assessments for high-risk AI systems, a step toward regulating discriminatory technologies. Additionally, governments and corporations should invest in bridging the digital divide, offering subsidies for broadband access and affordable devices. Finally, users must demand better—questioning the ethics behind the tools they use and advocating for change. Only then can technology serve as a force for equity rather than exclusion.

Mastering Political Research: Essential Strategies for Effective Analysis and Insights

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Political symbolism: Objects often represent power, ideology, or resistance in societies

Objects, seemingly inert and devoid of intent, often become vessels of profound political symbolism. Consider the Berlin Wall, a physical barrier that transcended its concrete and wire composition to embody the ideological divide between East and West during the Cold War. Its very existence was a statement of control, its graffiti-covered remnants a testament to resistance and the human desire for freedom. This example illustrates how objects can become powerful symbols, their meaning shaped by the societal and historical contexts in which they are situated.

A flag, for instance, is more than just a piece of cloth. Its colors, patterns, and symbols condense complex national identities, histories, and aspirations into a singular, recognizable form. The American flag, with its stars and stripes, represents not just a nation but ideals of liberty and democracy, often invoked in political rhetoric and protest alike. Conversely, the burning of a flag can be a potent act of defiance, a rejection of the values it symbolizes. This duality highlights the dynamic nature of political symbolism, where objects can both unite and divide, depending on the perspective of the beholder.

To understand the political symbolism of objects, one must analyze their design, usage, and the narratives that surround them. Take the AK-47, a weapon designed for its functionality and reliability, yet it has become an icon of revolution and resistance in many parts of the world. Its image appears on flags, currency, and even in art, symbolizing both the struggle for liberation and the pervasive nature of conflict. This transformation from tool to symbol underscores the ability of objects to transcend their original purpose and acquire new meanings that resonate deeply within societies.

Incorporating political symbolism into everyday life requires a critical eye and an awareness of the messages being conveyed. For educators and parents, discussing the symbolism behind common objects can foster a deeper understanding of history and politics. For activists, leveraging the symbolic power of objects can amplify their message and mobilize communities. For designers and creators, being mindful of the potential political implications of their work ensures that their creations contribute positively to societal discourse. By recognizing and engaging with the political symbolism of objects, individuals can navigate and influence the narratives that shape their world.

Ultimately, the political symbolism of objects serves as a reminder that the material world is deeply intertwined with our social and political realities. From the crown that signifies monarchy to the ballot box that embodies democracy, these objects are not mere tools or decorations; they are carriers of meaning, reflecting and reinforcing the power structures, ideologies, and resistance movements that define our societies. By examining these symbols, we gain insight into the values and conflicts that shape our collective experience, making the study of political symbolism an essential lens through which to understand the world.

Are Politics Degrees Worth It? Weighing Career Benefits and Challenges

You may want to see also

Environmental impact: Artefacts' production and use reflect political choices about sustainability

The environmental footprint of a single smartphone is staggering: approximately 85 kg of CO2 emissions, equivalent to driving a car for 300 miles. This fact alone underscores how artefacts—from the devices in our pockets to the cars in our garages—are not neutral objects but embodiments of political decisions about resource extraction, manufacturing processes, and consumer culture. Every stage of an artefact’s lifecycle, from mining rare earth metals to disposal, reflects choices made by governments, corporations, and societies about sustainability. These choices are inherently political, prioritizing economic growth, technological advancement, or environmental preservation—often at the expense of one another.

Consider the production of fast fashion, an industry responsible for 10% of global carbon emissions. The decision to produce cheap, disposable clothing instead of durable, sustainable garments is a political one, driven by policies that favor low labor costs and lax environmental regulations. Consumers are often led to believe that affordability is the primary goal, but this narrative obscures the environmental and social costs. For instance, the use of synthetic fibers like polyester, derived from fossil fuels, contributes to microplastic pollution in oceans. By contrast, policies that incentivize circular fashion—such as tax breaks for recycled materials or extended producer responsibility laws—could shift the industry toward sustainability. This example illustrates how artefacts are not just products of design but also of political and economic systems.

To mitigate the environmental impact of artefacts, individuals and policymakers must take deliberate, informed action. Start by assessing the lifecycle of products before purchase: opt for items with minimal packaging, made from recycled materials, or designed for longevity. For instance, choosing a laptop with an upgradeable design can extend its lifespan by 5–7 years, reducing e-waste. Policymakers can amplify this impact by mandating right-to-repair laws, which empower consumers to fix devices instead of replacing them. Additionally, carbon labeling on products could raise awareness of their environmental footprint, much like nutritional labels inform dietary choices. These steps require political will but can transform artefacts from agents of harm into tools of sustainability.

A comparative analysis of two artefacts—a conventional incandescent bulb and an LED bulb—highlights the political dimensions of sustainability. Incandescent bulbs, once ubiquitous, are energy-inefficient, converting only 5% of electricity into light. Their continued use in some regions reflects political inertia or resistance to change. In contrast, LED bulbs, which consume 75% less energy and last 25 times longer, are the product of policies promoting innovation and energy efficiency. The phase-out of incandescent bulbs in the EU and US was not merely a technological shift but a political decision to prioritize environmental goals. This comparison shows how artefacts can either perpetuate or challenge unsustainable systems, depending on the choices made by those in power.

Ultimately, the environmental impact of artefacts is a mirror reflecting our collective political priorities. Every artefact tells a story of the resources we exploit, the waste we generate, and the futures we choose to build. By recognizing this, we can reframe sustainability not as a personal responsibility but as a political imperative. Whether through consumer choices, advocacy, or policy reform, we have the power to reshape the lifecycle of artefacts—and, in doing so, to redefine what it means for technology to serve humanity and the planet. The question is not whether artefacts have politics, but whether we will use their production and use to advance a sustainable future.

Constructing Political Culture: Influences, Processes, and Societal Shaping Factors

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The statement suggests that technological artefacts (tools, systems, designs) are not neutral but embody values, biases, and political assumptions of their creators, influencing society in specific ways.

The phrase is often attributed to Langdon Winner, who explored the idea in his 1980 essay "Do Artifacts Have Politics?" published in *Daedalus*.

A common example is the design of low bridges in Long Island, New York, which prevented buses from accessing certain areas, effectively excluding lower-income individuals and reinforcing social inequality.

Not necessarily. While some artefacts may reflect deliberate political intentions, others may embody politics unintentionally through design choices, cultural biases, or societal norms.