The origins of political parties in the United States are often traced back to the early years of the republic, despite the Founding Fathers' initial skepticism and warnings against faction. Emerging in the 1790s, the first political parties—the Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, and the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson—formed around differing visions for the nation's future. While these parties were born out of genuine ideological divides, such as the role of the federal government and economic policies, their creation was not universally viewed as favorable. Critics, including George Washington, feared that partisanship would undermine national unity and lead to divisive conflicts. Despite these concerns, the early parties played a crucial role in shaping American democracy, providing organized platforms for competing ideas and mobilizing public support, though their inception marked the beginning of a contentious and enduring feature of U.S. politics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origin of Political Parties | Political parties in the United States emerged in the 1790s during George Washington's presidency, primarily as a result of differing views on the role of the federal government and economic policies. |

| First Political Parties | The first two major political parties were the Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, and the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson. |

| Federalist Party | Favored a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain. Supported by urban merchants and financiers. |

| Democratic-Republican Party | Advocated for states' rights, agrarian interests, and a limited federal government. Supported by farmers, planters, and the rural population. |

| Washington's Stance | George Washington opposed the formation of political parties, warning against their divisive nature in his Farewell Address (1796). |

| Public Perception | Initially, political parties were viewed with skepticism and concern, as they were seen as threatening national unity and fostering factionalism. |

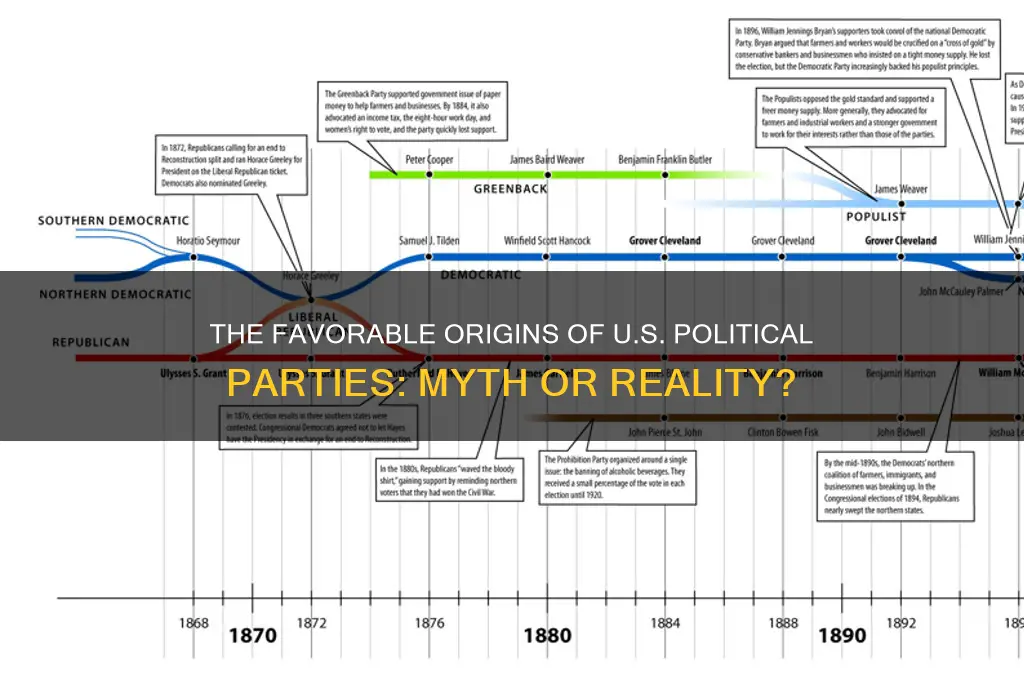

| Evolution of Favorability | Over time, parties became accepted as essential for organizing political competition, mobilizing voters, and structuring governance. |

| Modern Perspective | Today, political parties are considered a fundamental aspect of the U.S. political system, though their favorability fluctuates based on public trust and partisan polarization. |

| Current Party System | The U.S. has a dominant two-party system (Democrats and Republicans), with third parties playing a minor role in national politics. |

| Public Opinion (Latest Data) | As of recent polls (e.g., Pew Research, Gallup), political parties have low favorability ratings, with increasing dissatisfaction due to polarization and gridlock. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Early Party Formation: Federalists vs. Democratic-Republicans

The emergence of political parties in the United States was not initially viewed favorably by the nation's founding fathers, who saw them as a threat to unity and stability. George Washington, in his Farewell Address, warned against the "baneful effects of the spirit of party," fearing it would lead to division and undermine the young republic. Despite this caution, the first political parties—the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans—formed during the 1790s, largely as a result of differing visions for the nation's future. These parties were not born out of favorability but out of necessity, as leaders like Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson clashed over fundamental issues such as the role of government, economic policy, and the interpretation of the Constitution.

The Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, emerged as the first organized political party in the United States. They favored a strong central government, believing it was essential for national stability and economic growth. Hamilton's financial policies, including the establishment of a national bank and the assumption of state debts, were central to the Federalist agenda. Federalists also tended to align with wealthy merchants, industrialists, and urban elites, who benefited from their policies. They interpreted the Constitution broadly, advocating for implied powers to achieve their goals. Federalists were particularly strong in the Northeast, where their vision of a commercial and industrialized nation resonated with the region's economic interests.

In contrast, the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, emerged as a counterforce to the Federalists. They championed states' rights, limited government, and agrarian interests, fearing that a strong central government would lead to tyranny. Jeffersonians opposed Hamilton's financial plans, arguing they favored the wealthy at the expense of the common man. They also criticized the Federalists' interpretation of the Constitution, insisting on a strict construction of the document. The Democratic-Republicans drew their support from the South and West, where agriculture dominated the economy, and from small farmers and artisans who felt marginalized by Federalist policies.

The rivalry between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans intensified during the 1790s, particularly over foreign policy. The French Revolution divided the parties, with Federalists favoring Britain and Democratic-Republicans sympathizing with France. This tension culminated in the Quasi-War with France and the Alien and Sedition Acts, which the Federalists passed to suppress dissent. These actions further polarized the nation and solidified party identities. The election of 1800, in which Jefferson defeated Federalist incumbent John Adams, marked a pivotal moment in early party formation, as it demonstrated the peaceful transfer of power between opposing parties—a critical test of the young democracy.

While the formation of these early parties was not initially viewed favorably, it ultimately became a cornerstone of American politics. The Federalist and Democratic-Republican rivalry established a framework for political competition and debate that continues to shape the nation. Their disagreements over the role of government, economic policy, and constitutional interpretation laid the groundwork for enduring political divisions in the United States. Despite the founders' initial concerns, the two-party system emerged as a mechanism for organizing political conflict and ensuring that diverse interests were represented in governance.

Can Political Parties Swap Candidates? Rules, Reasons, and Realities Explained

You may want to see also

Role of Key Figures: Jefferson, Hamilton, and Adams

The emergence of political parties in the United States during the late 18th century was deeply influenced by the visions and conflicts of key figures such as Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and John Adams. These leaders, though united in their commitment to the young nation, held fundamentally different ideologies that laid the groundwork for the first political parties. Their roles were pivotal in shaping the early party system, which, while contentious, became a cornerstone of American democracy.

Thomas Jefferson played a central role in the formation of the Democratic-Republican Party, which opposed the Federalist Party led by Hamilton and Adams. Jefferson’s vision emphasized states’ rights, agrarian interests, and a limited federal government. He feared that a strong central government, as advocated by the Federalists, would lead to tyranny and undermine individual liberties. Jefferson’s authorship of the Declaration of Independence and his service as the nation’s third president gave him immense credibility, which he used to rally support for his party. His election in 1800, often referred to as the "Revolution of 1800," marked the first peaceful transfer of power between opposing political parties in the U.S., demonstrating that political parties could function within a democratic framework.

Alexander Hamilton, on the other hand, was a staunch advocate for a strong federal government and a national economy. As the first Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton’s policies, such as the establishment of a national bank and the assumption of state debts, were central to the Federalist agenda. His vision of a commercially oriented nation clashed directly with Jefferson’s agrarian ideal. Hamilton’s influence extended beyond policy; he was a key figure in organizing the Federalist Party, which sought to consolidate power at the federal level. While his ideas were initially favorable to the nation’s economic development, they also sowed the seeds of partisan division, as Jefferson and his followers viewed Hamilton’s policies as elitist and undemocratic.

John Adams, the second president of the United States, occupied a complex position between Jefferson and Hamilton. As a Federalist, Adams aligned with Hamilton’s vision of a strong central government, but he was less enthusiastic about Hamilton’s financial policies. Adams’s presidency was marked by increasing polarization between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, particularly during the Quasi-War with France. His signing of the Alien and Sedition Acts, which restricted civil liberties, further alienated Jeffersonian Republicans and deepened partisan divides. Despite his contributions to the nation’s early governance, Adams’s inability to bridge the growing ideological gap highlighted the challenges of the emerging party system.

The interactions and conflicts among Jefferson, Hamilton, and Adams were instrumental in the development of political parties in the United States. Their differing visions of governance—Jefferson’s agrarian democracy, Hamilton’s commercial federalism, and Adams’s moderate federalism—created a framework for organized political opposition. While their rivalries often led to bitter disputes, they also established a precedent for competitive politics. The early party system, though fraught with contention, ultimately proved favorable to the nation’s democratic evolution by providing mechanisms for representing diverse interests and ensuring peaceful transitions of power.

In conclusion, the roles of Jefferson, Hamilton, and Adams were indispensable in the formation and early dynamics of political parties in the United States. Their ideologies and actions not only defined the first parties but also set the stage for the enduring two-party system. While their conflicts underscored the challenges of partisan politics, their contributions ensured that political parties became a vital, if contentious, element of American democracy.

Courts and Politics: Impartial Justice or Partisan Tool?

You may want to see also

Impact of Elections: 1796 and 1800 as turning points

The elections of 1796 and 1800 were pivotal moments in American political history, marking significant turning points in the development and perception of political parties in the United States. By the mid-1790s, the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties had emerged as dominant forces, though their existence was initially met with skepticism by many of the Founding Fathers, including George Washington, who warned against the dangers of faction in his farewell address. The 1796 election, the first contested presidential election between two distinct parties, set the stage for the formalization of party politics. John Adams, the Federalist candidate, narrowly defeated Thomas Jefferson, the Democratic-Republican candidate, becoming the second president. This election demonstrated that political parties could effectively mobilize voters and compete for power, despite earlier reservations about their role in governance.

The 1796 election also highlighted the growing ideological divide between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, favored a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain, while Democratic-Republicans, led by Jefferson, advocated for states' rights, agrarianism, and alignment with France. This ideological split became more pronounced during Adams's presidency, as disputes over foreign policy, taxation, and the Alien and Sedition Acts deepened partisan tensions. The election of 1796 thus served as a turning point by legitimizing party competition and embedding it into the American political system, even as it exposed the challenges of managing partisan conflict.

The election of 1800 further solidified the role of political parties and marked a critical turning point in American democracy. Often referred to as the "Revolution of 1800," this election saw Thomas Jefferson defeat John Adams in a contentious race that initially resulted in an Electoral College tie between Jefferson and his running mate, Aaron Burr. The House of Representatives ultimately resolved the deadlock in Jefferson's favor, but the process revealed flaws in the electoral system, leading to the passage of the 12th Amendment in 1804. This election demonstrated the resilience of the Constitution and the ability of political parties to navigate a peaceful transfer of power, even in the face of intense partisan rivalry.

The 1800 election also represented a shift in political power from the Federalists to the Democratic-Republicans, signaling the ascendancy of Jeffersonian ideals. Jefferson's victory was celebrated as a triumph of the "people's party" over the perceived elitism of the Federalists, and it ushered in an era of Democratic-Republican dominance. This transition underscored the growing acceptance of political parties as essential mechanisms for representing diverse interests and ideologies in a rapidly expanding nation. While the Founding Fathers had initially viewed parties with suspicion, the elections of 1796 and 1800 demonstrated that they had become indispensable to American politics.

In conclusion, the elections of 1796 and 1800 were turning points that shaped the trajectory of political parties in the United States. They legitimized party competition, exposed and addressed structural weaknesses in the electoral system, and facilitated a peaceful transfer of power between opposing factions. These elections also deepened the ideological divide between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, setting the stage for future partisan dynamics. While political parties did not begin entirely favorably, as evidenced by early concerns about factionalism, these elections proved their enduring role in American governance. By the early 19th century, parties had become central to the nation's political landscape, a transformation that began in earnest with the contests of 1796 and 1800.

State vs. National Political Parties: Are Their Identities Truly Aligned?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$28.31 $42

Public Perception: Initial skepticism and growing acceptance

The emergence of political parties in the United States during the late 18th century was met with considerable skepticism and concern from the public. Many of the nation's founding fathers, including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, initially viewed political parties as divisive and detrimental to the unity of the young republic. In his Farewell Address, Washington warned against the "baneful effects of the spirit of party," fearing that factions would undermine the common good and lead to conflict. This sentiment was widely shared among early Americans, who had just fought a revolution to escape what they saw as the corrupt and factionalized politics of colonial rule. As a result, the first political parties, such as the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans, were not initially embraced by the public but rather viewed with suspicion.

The initial skepticism toward political parties stemmed from their perceived threat to democratic ideals and national cohesion. Many citizens believed that parties would prioritize their own interests over those of the nation, leading to corruption and gridlock. The Federalist Party, led by Alexander Hamilton, was particularly mistrusted by those who saw it as elitist and favoring the wealthy. Similarly, the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson, was criticized by Federalists for appealing to the uneducated masses and threatening the stability of the government. This mutual distrust fueled a narrative that political parties were inherently harmful, and their rise was often portrayed as a betrayal of the revolutionary ideals of unity and public virtue.

Despite this early skepticism, public perception of political parties began to shift as they demonstrated their ability to organize and mobilize voters. Parties became essential mechanisms for political participation, providing a structure through which citizens could engage with the government and advocate for their interests. The 1796 and 1800 presidential elections, contested between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, marked a turning point, as they showed that parties could facilitate peaceful transitions of power. This growing acceptance was further bolstered by the realization that parties could serve as checks on governmental power, preventing any single faction from dominating the political landscape.

Over time, the practical benefits of political parties became more apparent, leading to their gradual normalization in American politics. By the early 19th century, parties were no longer seen as inevitable evils but as necessary tools for democratic governance. They provided a means for citizens to coalesce around shared ideals, fostering a sense of political identity and community. The rise of newspapers affiliated with political parties also played a crucial role in shaping public opinion, as they disseminated information and rallied support for party platforms. This growing acceptance was reflected in the expansion of party systems at both the state and national levels, solidifying their role in American political life.

By the mid-19th century, political parties had become a cornerstone of the U.S. political system, with public perception largely moving from skepticism to acceptance. While concerns about partisanship and corruption persisted, the majority of Americans recognized the value of parties in representing diverse interests and facilitating political participation. The evolution of public opinion highlights the transformative role of political parties in shaping the nation's democratic institutions. What began as a contentious innovation eventually became an integral part of American governance, reflecting the dynamic and adaptive nature of the country's political culture.

Interest Groups vs. Political Parties: Who Holds More Power in Politics?

You may want to see also

Constitutional Concerns: Founders' warnings about factions

The founding fathers of the United States, particularly James Madison and George Washington, expressed significant concerns about the emergence of political factions, which would later evolve into political parties. These concerns were rooted in their understanding of human nature and the potential dangers factions posed to the stability and effectiveness of the new government. In Federalist Paper No. 10, Madison famously argued that factions, or groups of citizens with interests contrary to the rights of others or the interests of the whole, were inevitable in a free society. However, he warned that these factions could lead to instability, oppression, and the subversion of the democratic process if left unchecked. Madison’s solution was to create a large, diverse republic where the multiplicity of interests would make it difficult for any one faction to dominate.

George Washington, in his Farewell Address of 1796, further emphasized the dangers of political factions, referring to them as the "banes of republican government." He cautioned that parties could foster a spirit of revenge, encourage foreign influence, and divert the government from its primary purpose of serving the common good. Washington feared that partisan politics would place loyalty to party above loyalty to the nation, leading to divisiveness and undermining the unity necessary for a functioning democracy. His warnings reflected a deep skepticism about the long-term consequences of party politics on the nation’s cohesion and governance.

The founders’ concerns were not merely theoretical but were grounded in their experiences with political divisions during and after the Revolutionary War. They witnessed how factions could polarize society, hinder decision-making, and erode public trust in government. For instance, the debates over the ratification of the Constitution highlighted the challenges of balancing diverse interests and preventing the dominance of any single group. The founders sought to create a system that would mitigate these risks, emphasizing checks and balances, federalism, and a separation of powers to prevent faction dominance.

Despite these warnings, political parties began to emerge almost immediately after the Constitution’s ratification, with the Federalists and Anti-Federalists becoming the first major factions. This development was not viewed favorably by many founders, who saw it as a betrayal of their vision for a non-partisan government. The rise of parties underscored the tension between the idealistic principles of the Constitution and the practical realities of political organization. While parties provided a means for mobilizing public opinion and organizing political competition, they also introduced the very dangers the founders had sought to avoid.

In conclusion, the founders’ warnings about factions were a central aspect of their constitutional concerns and reflected their deep apprehension about the potential for political parties to undermine the republic. Their insights remain relevant today, as the United States continues to grapple with the challenges of partisan polarization and its impact on governance. Understanding these warnings provides valuable context for evaluating the role of political parties in American democracy and the ongoing efforts to address their negative consequences.

Are We Ready for a Second Political Party?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political parties in the United States did not begin favorably; they were initially viewed with skepticism by the Founding Fathers, including George Washington, who warned against the "baneful effects of the spirit of party" in his Farewell Address.

The first political parties, the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans, emerged in the 1790s during the presidency of George Washington, primarily due to differing views on the role of the federal government and the Constitution.

Political parties were initially controversial because they were seen as divisive, undermining unity and potentially leading to factions that prioritized party interests over the common good, as warned by the Founding Fathers.

Early political parties, despite initial opposition, became essential to American politics by organizing voters, structuring elections, and providing platforms for competing ideas, ultimately becoming a cornerstone of the U.S. political system.