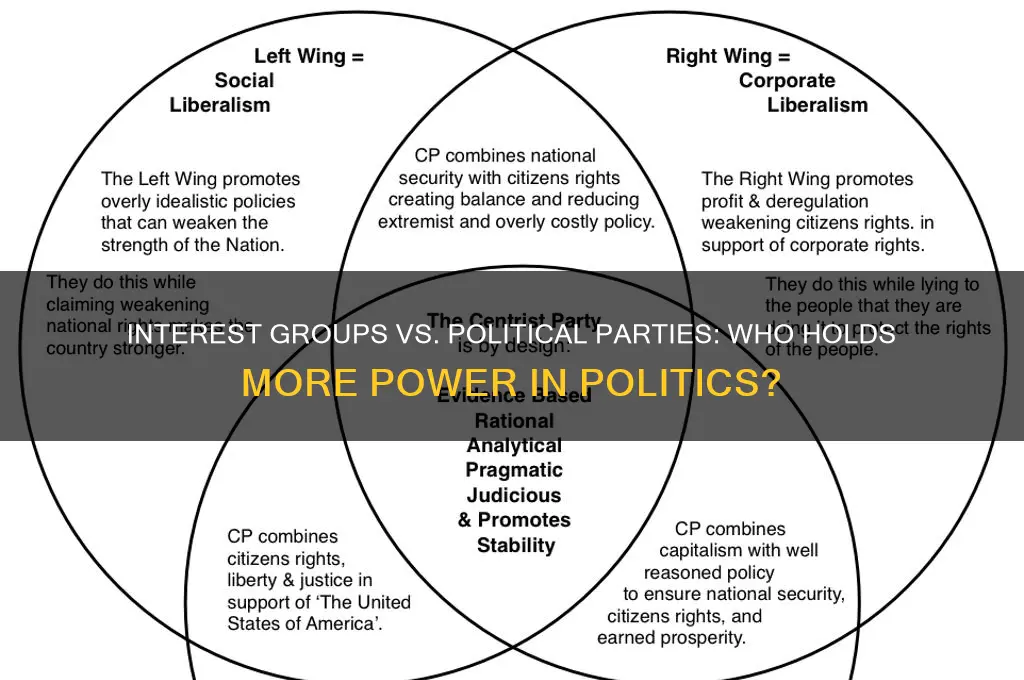

Interest groups and political parties are both integral to the functioning of democratic systems, yet their roles, structures, and influences differ significantly, raising the question: are interest groups bigger than political parties? While political parties primarily focus on winning elections, forming governments, and implementing broad policy agendas, interest groups are specialized organizations that advocate for specific issues or constituencies, often operating outside the electoral process. Interest groups can wield substantial power through lobbying, grassroots mobilization, and financial resources, sometimes surpassing the influence of political parties on particular issues. However, political parties maintain a broader scope, representing diverse interests and shaping the overall political landscape. The comparison hinges on whether bigger refers to scope, resources, or impact, making it a nuanced debate that highlights the complex interplay between these two pillars of modern politics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Membership Size | Interest groups often have larger memberships than political parties due to their focus on specific issues, attracting niche audiences. |

| Scope of Influence | Interest groups typically focus on specific issues or sectors, while political parties aim for broader governance and policy control. |

| Funding Sources | Interest groups rely on donations, memberships, and grants, whereas political parties depend on donations, fundraising, and public funding. |

| Organizational Structure | Interest groups are often decentralized and issue-specific, while political parties have hierarchical structures with national and local chapters. |

| Political Participation | Interest groups engage in lobbying, advocacy, and awareness campaigns, whereas political parties focus on elections, candidate nominations, and policy implementation. |

| Geographical Reach | Interest groups can be local, national, or international, while political parties are primarily national or regional in scope. |

| Longevity | Interest groups may dissolve once their goals are achieved, whereas political parties aim for long-term survival and influence. |

| Public Visibility | Political parties are more visible during elections, while interest groups gain visibility during specific campaigns or crises. |

| Decision-Making Power | Political parties have direct decision-making power when in government, while interest groups influence policy indirectly through advocacy. |

| Ideological Alignment | Interest groups are issue-driven and may not align with a specific ideology, whereas political parties are often ideologically driven. |

| Latest Data (as of 2023) | In the U.S., interest groups like the NRA or Sierra Club have millions of members, while major political parties (Democrats, Republicans) have fewer registered members but broader electoral influence. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Funding Sources: Interest groups vs. parties in campaign financing and donor influence

- Membership Size: Comparing active members in interest groups versus political parties

- Policy Impact: Which entity shapes legislation more effectively in government

- Public Reach: Media presence and grassroots mobilization capabilities of both groups

- Organizational Structure: Centralized parties vs. decentralized interest group networks

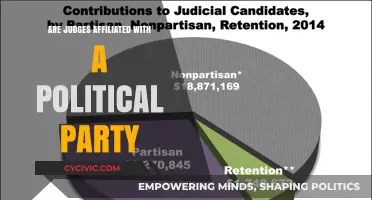

Funding Sources: Interest groups vs. parties in campaign financing and donor influence

The comparison of funding sources between interest groups and political parties reveals significant differences in campaign financing and donor influence. Interest groups, often representing specific industries, causes, or ideologies, rely heavily on membership dues, donations from individuals and corporations, and grants from foundations. These groups frequently advocate for narrow policy goals, making them attractive to donors who seek targeted outcomes. For instance, environmental organizations may receive funding from eco-conscious philanthropists, while business associations are supported by corporations aiming to shape regulatory policies. This focused funding model allows interest groups to mobilize resources efficiently for lobbying and advocacy campaigns.

In contrast, political parties typically have broader funding bases, including individual donations, corporate contributions, and public financing in some countries. Parties are required to appeal to a wider electorate, which often necessitates balancing diverse interests. While parties may receive large donations from wealthy individuals or corporations, they also depend on small-dollar contributions from grassroots supporters. Public financing, where available, provides parties with a stable source of funding but often comes with spending limits and transparency requirements. This broader funding approach enables parties to finance election campaigns, maintain organizational structures, and promote their platforms across various demographics.

Donor influence differs markedly between interest groups and parties. Interest groups often provide a direct return on investment for donors by advocating for specific policies that align with their interests. For example, a pharmaceutical company donating to a healthcare advocacy group may expect support for favorable drug pricing policies. This transactional nature of funding can lead to significant donor influence over the group's agenda. Political parties, however, must navigate a more complex relationship with donors, as they need to maintain public trust while securing funds. While large donors may gain access to party leaders or influence policy discussions, parties are generally more accountable to their voter base, which acts as a check on donor dominance.

Transparency and regulation further distinguish the funding landscapes of interest groups and parties. In many jurisdictions, political parties are subject to stricter disclosure requirements and spending limits, particularly during election periods. Interest groups, especially those not directly involved in electoral campaigns, may face fewer regulatory constraints, allowing them to operate with greater opacity. This disparity can lead to concerns about the outsized influence of interest groups, particularly when they engage in "dark money" spending through nonprofit arms. Such practices highlight the challenges in regulating campaign financing and ensuring equitable donor influence across both entities.

Ultimately, the funding sources and donor influence dynamics of interest groups and political parties reflect their distinct roles in the political ecosystem. Interest groups thrive on targeted funding and direct advocacy, making them powerful players in shaping specific policies. Political parties, with their broader funding bases and public accountability, focus on winning elections and governing. Understanding these differences is crucial for assessing whether interest groups are indeed "bigger" than political parties, as their influence often hinges on their ability to mobilize resources and sway decision-makers in unique and complementary ways.

Are Membership Dues Mandatory for Joining a Political Party?

You may want to see also

Membership Size: Comparing active members in interest groups versus political parties

When comparing the membership size of interest groups and political parties, it's essential to consider the nature of participation in each. Political parties typically rely on formal membership structures, where individuals officially register, pay dues, and actively engage in party activities. In many democracies, major political parties boast significant membership numbers. For instance, in countries like Germany or Sweden, established parties can have hundreds of thousands or even millions of registered members. However, the number of active members—those who regularly participate in meetings, campaigns, or decision-making processes—is often a fraction of the total membership. Studies suggest that only 10-20% of registered party members are consistently active, meaning that while parties may have large membership rolls, their core active base is relatively smaller.

In contrast, interest groups often operate with a different membership model, focusing on issue-based engagement rather than formal registration. Many interest groups, such as environmental organizations or labor unions, have large supporter bases but rely heavily on a smaller core of active participants. For example, organizations like the Sierra Club or the National Rifle Association (NRA) in the United States may have millions of supporters or donors, but their active membership—those who attend events, lobby, or organize campaigns—is typically much smaller. This distinction highlights that while interest groups can mobilize large numbers for specific causes, their active membership size is often comparable to or even smaller than that of political parties, despite their broader reach.

Another factor to consider is the geographic and demographic scope of membership. Political parties generally aim for broad national representation, with members spread across regions and demographics. Interest groups, however, often focus on specific issues or communities, which can limit their active membership size but deepen their engagement within those niches. For instance, a local environmental group may have fewer active members than a national political party but wield significant influence in its specific area of concern. This localized focus can make interest groups appear smaller in membership size compared to parties, even if their impact is substantial.

Furthermore, participation dynamics differ significantly between the two. Political parties require sustained engagement in electoral processes, policy development, and internal governance, which can be demanding for members. Interest groups, on the other hand, often offer more flexible participation options, such as signing petitions, donating, or attending occasional events. This flexibility can attract a larger overall supporter base but may result in a smaller core of consistently active members. As a result, while interest groups may seem larger due to their broad support, their active membership size often does not surpass that of political parties, which maintain more structured and sustained participation.

In conclusion, comparing active membership size between interest groups and political parties reveals nuanced differences. Political parties tend to have larger formal membership rolls, but their active base is often limited to a dedicated minority. Interest groups, while capable of mobilizing vast numbers for specific causes, typically rely on smaller cores of active participants. Ultimately, neither is universally "bigger" in terms of active membership; the comparison depends on the context, structure, and goals of each organization. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for assessing the relative influence and capacity of interest groups and political parties in shaping public policy and discourse.

Are Political Party Donations Tax Deductible? What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Policy Impact: Which entity shapes legislation more effectively in government

The question of whether interest groups or political parties have a greater impact on shaping legislation is a complex one, and the answer often depends on the specific context and political system in question. Both entities play significant roles in the policy-making process, but their influence can vary widely. When considering policy impact, it is essential to examine the mechanisms through which these groups and parties exert their influence and the factors that contribute to their effectiveness.

Interest Groups and Their Policy Influence:

Interest groups, also known as advocacy groups or lobby groups, are organized collections of individuals or organizations that aim to influence public policy. These groups can represent a wide range of interests, including business, labor, environmental concerns, social issues, and more. One of the key strengths of interest groups lies in their ability to specialize and focus on specific policy areas. They often possess extensive expertise and resources related to their particular cause, enabling them to provide valuable insights and information to policymakers. For instance, an environmental interest group might have detailed knowledge about climate change legislation and propose specific amendments or alternatives. This specialized knowledge can make interest groups highly effective in shaping the technical aspects of policies. Moreover, interest groups can mobilize their members and supporters to engage in various advocacy activities, such as lobbying, public demonstrations, and media campaigns, which can capture the attention of policymakers and the public alike.

In many political systems, interest groups have direct access to policymakers through lobbying efforts. They can meet with legislators, provide research and data, and offer suggestions for policy changes. This direct engagement allows interest groups to influence the legislative process at various stages, from agenda-setting to the final drafting of bills. For example, a powerful business interest group might lobby for tax incentives or regulatory changes that benefit their industry. Over time, consistent and well-organized lobbying efforts can lead to significant policy shifts.

Political Parties and Legislative Power:

Political parties, on the other hand, are fundamental organizations in representative democracies, and their role in shaping legislation is inherent in the political process. Parties aggregate interests and provide a platform for like-minded individuals to come together and pursue common policy goals. They play a crucial role in electing representatives and forming governments, which gives them substantial power in the policy-making process. When a political party wins an election, it typically has a mandate to implement its campaign promises and policy agenda. This mandate provides a strong basis for influencing legislation.

The impact of political parties on policy is often more comprehensive and far-reaching compared to interest groups. Parties can shape the overall direction of government policies and set the agenda for legislative priorities. They have the power to introduce and control the flow of bills in the legislature, ensuring that their preferred policies receive attention and debate. Additionally, political parties can utilize their majority or coalition strength to pass legislation, especially in systems where party discipline is strong. This ability to control the legislative process and ensure policy implementation is a significant advantage for political parties.

Comparing Effectiveness:

Determining which entity is more effective in shaping legislation requires considering several factors. Interest groups may have an edge when it comes to specific, technical policy details due to their specialized knowledge. They can influence the nuances of legislation and ensure that their particular interests are addressed. However, political parties have the advantage of a broader mandate and control over the legislative agenda. They can set the overall policy framework and prioritize issues, which can significantly impact the direction of government actions.

In many cases, the relationship between interest groups and political parties is symbiotic. Interest groups provide valuable support to parties during elections, and in return, they gain access and influence over policymakers. This relationship can lead to a more effective policy impact as interest groups align their efforts with the governing party's agenda. Ultimately, the effectiveness of each entity depends on various factors, including the political system, the specific policy area, and the organizational strength of the groups and parties involved. In some instances, interest groups might dominate policy discussions, while in others, political parties may exert more control. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for comprehending the complex interplay between interest groups and political parties in the policy-making process.

Are Political Party Donations Tax Exempt? Understanding the Rules

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Public Reach: Media presence and grassroots mobilization capabilities of both groups

In the debate over whether interest groups are bigger than political parties, public reach—encompassing media presence and grassroots mobilization capabilities—emerges as a critical factor. Political parties traditionally dominate media landscapes due to their central role in elections and governance. They receive extensive coverage during campaigns, with candidates and party leaders frequently featured in news outlets, debates, and prime-time broadcasts. This visibility is amplified by their structured communication networks, which include press teams, official spokespersons, and established relationships with journalists. Interest groups, while often lacking this institutional access, have carved out significant media space by leveraging targeted messaging and niche issues. They employ press releases, op-eds, and social media campaigns to spotlight specific causes, sometimes gaining traction through viral content or by aligning with trending narratives. However, their media presence is typically issue-specific and episodic, whereas political parties maintain a more consistent, broad-based visibility.

Grassroots mobilization is another arena where the two groups diverge. Political parties rely on their established networks of local chapters, volunteers, and door-to-door campaigns to reach voters. Their mobilization efforts are often tied to election cycles, focusing on voter registration, turnout, and canvassing. This structured approach allows them to activate large numbers of supporters during critical periods. Interest groups, on the other hand, excel in issue-driven mobilization, harnessing passion and urgency around specific causes. They utilize digital tools, such as email campaigns, petitions, and crowdfunding, to engage supporters rapidly and at scale. Grassroots movements like those organized by environmental or civil rights groups often demonstrate the ability to galvanize diverse, decentralized networks, sometimes rivaling the reach of political parties in specific contexts. However, while interest groups may achieve greater intensity in mobilization, political parties maintain an edge in breadth and sustained engagement.

The rise of social media has reshaped the public reach dynamics between interest groups and political parties. Interest groups have capitalized on platforms like Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok to bypass traditional media gatekeepers and connect directly with audiences. Their ability to craft viral content and mobilize online communities has allowed them to compete with political parties in terms of visibility and engagement. Political parties, while also active on social media, often face challenges in matching the agility and creativity of interest groups. However, parties benefit from their broader appeal and ability to integrate social media into larger, multi-channel strategies that include television, radio, and in-person events. This hybrid approach enables them to maintain a more comprehensive public reach, even as interest groups dominate certain digital spaces.

Despite these differences, collaboration between interest groups and political parties can amplify their collective public reach. Interest groups often partner with parties to advance shared agendas, leveraging their mobilization capabilities to bolster party campaigns. Conversely, parties provide interest groups with access to broader audiences and institutional platforms. This symbiotic relationship highlights that while interest groups may excel in specific areas of public reach, political parties retain a structural advantage in terms of sustained media presence and nationwide mobilization. Ultimately, the "bigness" of either group in terms of public reach depends on the context—whether measured by intensity of engagement, breadth of visibility, or ability to influence public discourse.

In conclusion, both interest groups and political parties possess distinct strengths in media presence and grassroots mobilization. Political parties maintain a dominant position in traditional media and structured mobilization, while interest groups thrive in issue-specific campaigns and digital engagement. The comparison underscores that "bigness" is not a one-dimensional concept but rather a function of the tools, strategies, and contexts each group leverages to reach the public. As media landscapes continue to evolve, the interplay between these two entities will remain a key factor in shaping public discourse and political outcomes.

Can Federal Employees Hold Political Party Office? Legal Insights

You may want to see also

Organizational Structure: Centralized parties vs. decentralized interest group networks

The organizational structures of political parties and interest groups differ significantly, particularly in terms of centralization versus decentralization. Political parties typically operate under a centralized structure, where decision-making authority is concentrated at the top levels of the organization. National party leaders, such as chairs or executive committees, set the agenda, coordinate campaigns, and allocate resources. This hierarchical model ensures unity and consistency in messaging and strategy, which is crucial for winning elections. For example, in the United States, the Democratic and Republican parties have clear chains of command, with state and local chapters often following directives from the national party apparatus. This centralization allows parties to mobilize large-scale campaigns and maintain a cohesive platform.

In contrast, interest groups generally function within a decentralized network structure. Instead of a single leadership body, interest groups often consist of multiple autonomous chapters, affiliates, or coalitions that operate independently while sharing common goals. This decentralization allows interest groups to be more flexible and responsive to local or specific issues. For instance, environmental organizations like the Sierra Club have national offices but rely heavily on local chapters to drive grassroots activism. Similarly, labor unions often have national leadership but are organized into local unions that address region-specific concerns. This network model enables interest groups to amplify diverse voices and adapt to varying contexts, making them highly effective in advocacy and mobilization.

The centralized nature of political parties provides them with a clear advantage in terms of resource allocation and strategic coordination. Parties can pool funds, deploy staff, and run coordinated campaigns across regions, which is essential for electoral success. However, this centralization can also lead to rigidity and a disconnect from local issues. Interest groups, on the other hand, thrive on their decentralized networks, which allow them to engage deeply with specific communities and issues. This flexibility often makes interest groups more agile in responding to emerging challenges, such as policy changes or social movements.

Another key difference lies in membership and participation. Political parties often have formal membership structures, with members paying dues and participating in party activities. However, membership tends to be less active compared to interest groups, where members are often deeply engaged in advocacy and activism. Interest groups frequently rely on volunteers and grassroots supporters who are passionate about specific causes, fostering a high level of participation. This engagement can make interest groups more influential in shaping public opinion and policy, even if they lack the formal power of elected officials.

In terms of size and scope, the question of whether interest groups are "bigger" than political parties depends on the metric used. Political parties have a broader mandate, encompassing a wide range of issues and constituencies, whereas interest groups focus on specific causes. While parties may have larger overall memberships, interest groups often boast more active and dedicated participants. Additionally, interest groups can form vast networks of alliances, amplifying their collective influence. For example, a coalition of environmental, labor, and civil rights groups can wield significant power by combining their resources and reach.

In conclusion, the centralized structure of political parties and the decentralized networks of interest groups reflect their distinct roles and strategies. Parties prioritize unity and coordination for electoral success, while interest groups emphasize flexibility and grassroots engagement for advocacy. Neither model is inherently superior; rather, their effectiveness depends on the context and goals. Understanding these structural differences is essential for analyzing whether interest groups are "bigger" than political parties, as size and influence are shaped by organizational design and operational focus.

Interest Groups vs. Political Parties: Understanding Their Distinct Roles and Functions

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Not necessarily. While some interest groups have large memberships, political parties often have broader and more extensive membership bases due to their national or regional reach and ideological appeal.

It depends on the context. Interest groups can wield significant influence through lobbying, funding, and mobilization, but political parties play a central role in governing and legislative processes, often giving them greater systemic power.

Yes, interest groups typically focus on specific issues or sectors, leading to greater diversity in their objectives. Political parties, on the other hand, have broader platforms that encompass multiple policy areas to appeal to a wider electorate.