The Vietnam War was the subject of widespread protests, which led to government attempts to limit First Amendment protections, particularly the right to assemble and free speech. The war was also challenged on constitutional grounds, with lawsuits arguing that only Congress could institute a military draft or formally declare war. Despite these challenges, the Supreme Court never explicitly ruled on the constitutionality of the war, leaving the presidential power to initiate wars largely unchecked.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Constitutional controversy | Wars can only be started by a formal declaration by Congress, not by the President |

| Supreme Court | Overturned Ali's conviction for draft evasion |

| Overturned an injunction against further publication of documents related to the war, citing violation of free press guarantees | |

| Upheld a law prohibiting the mutilation or burning of draft cards | |

| Rejected prior restraint on the press involving the publication of classified information | |

| Upheld the right of senators to read excerpts from the Pentagon Papers | |

| Protected the rights of congressional staffers under the Speech and Debate Clause | |

| Challengers' cases | Velvel v. President Johnson, based on claims that the war caused economic harm and diverted money needed for domestic programs |

| Holmes' appeal, repeatedly voted for by Justice Douglas |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The Supreme Court's silence on the constitutionality of the war

The Vietnam War was the subject of widespread protests, with many Americans questioning the constitutionality of the conflict. The war was never formally declared by Congress, and this, along with the government's attempts to limit First Amendment protections, led to significant public opposition.

Despite the controversy, the Supreme Court remained silent on the core constitutional question of the war's legality. This "strange silence", as described by Texas Tech law professor Rodric B. Schoen, had important implications for presidential power. By not addressing the issue, the Supreme Court allowed presidential authority to initiate wars without a formal declaration from Congress to remain largely unchecked.

One notable case that reached the Supreme Court was that of boxer Muhammad Ali, who challenged his draft evasion conviction. The Court overturned his conviction, ruling that the rejection of his conscientious objector claim was flawed. However, this ruling did not address the broader constitutionality of the war itself.

Another case, known as the Velvel lawsuit, was brought by a citizen who claimed that the war was invalid and had caused economic harm, diverted funds from domestic programs, and impacted friends and relatives serving in Vietnam. However, this lawsuit failed as the plaintiff could not demonstrate a personal injury caused by the war effort and was found to lack legal standing.

The Supreme Court's silence on the constitutionality of the Vietnam War stands in contrast to its rulings on other related matters. For instance, the Court upheld the right of senators to read excerpts from the Pentagon Papers, protecting free press guarantees, and rejected prior restraint on the press involving the publication of classified information.

How Actions Lead to Unforeseen Consequences

You may want to see also

Challenges to the draft

The Vietnam War was widely unpopular by early 1966, despite the repeated attempts by President Lyndon Johnson, his aides, and the generals to proclaim that US troops were winning. The war quickly became the focus of major protests, resulting in increased government attempts to limit First Amendment protections, dealing with the right to assemble and what constituted appropriate free speech criticism of the war.

Several challenges to the draft made it to the Supreme Court. One such case was that of Muhammad Ali, who successfully overturned his conviction for draft evasion. The Justices ruled in Ali's favour, concluding that the rejection of his conscientious objector claim was flawed. However, this ruling did not settle the question of whether the undeclared war in Vietnam was unconstitutional.

Another case that reached the Supreme Court concerned a law prohibiting the mutilation or burning of draft cards, which the Court upheld. The right of senators to read excerpts from the Pentagon Papers, classified documents suggesting that the government had misled the American people about the war, was also upheld by the Court, affirming the First Amendment's role as a check on governmental power.

The constitutional controversy over whether wars can only be started by a formal declaration by Congress, and not by the President, has been a long-standing debate in the United States. This dispute has roots in President James Polk's aggressive use of military force along the border with Mexico in 1845, which led Congress to enact a formal declaration of war. Since then, Congress has rarely used its constitutional power to formally declare war.

Constitutional Basis for Income Taxes: What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

The right to assemble and free speech criticism

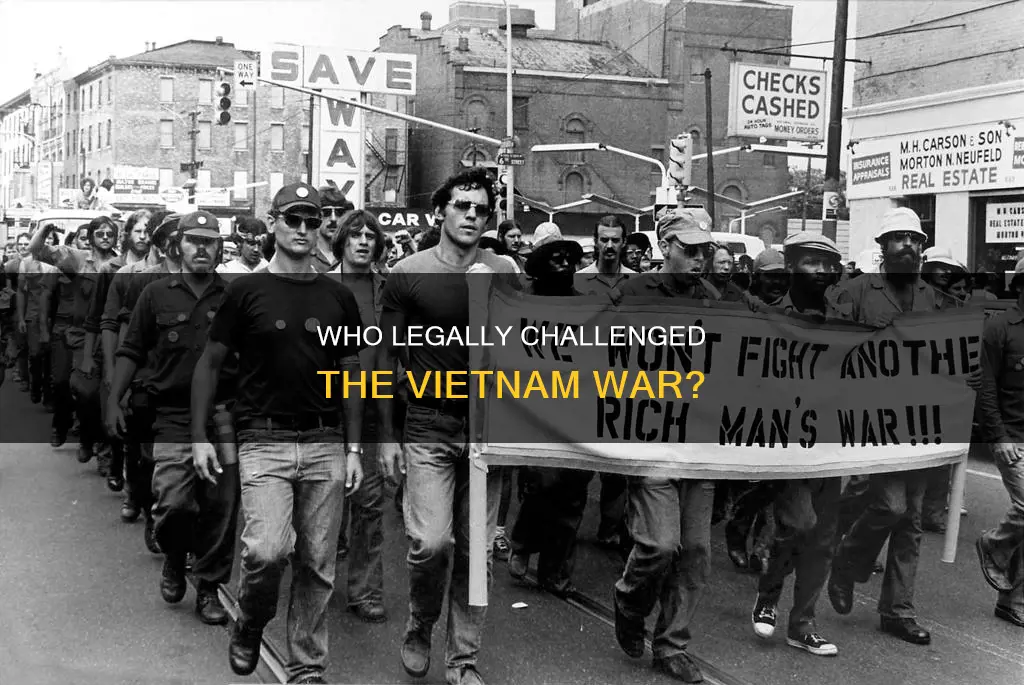

The Vietnam War was the focus of major protests that resulted in increased government attempts to limit First Amendment protections, particularly the right to assemble and free speech criticism.

The war in Vietnam became the focus of protests that resulted in government attempts to limit First Amendment protections, dealing with the right to assemble and what constituted appropriate free speech criticism of the war. The anti-war movement included students, civil rights groups, and returning veterans. The burning of draft cards became an important symbolic protest of the war.

The right to assemble, as protected by the First Amendment, was a crucial aspect of the anti-war protests. People gathered in large numbers to express their opposition to the war. For example, in October 1967, a protest on the Mall in Washington, DC, attracted 100,000 people, many of whom then marched to the Pentagon to continue the protest. Similarly, in 1965, there were two protest marches on Washington, DC, both attracting thousands of people. These demonstrations played a significant role in shaping public opinion and influencing government actions regarding the war.

Free speech criticism was also a vital component of the opposition to the Vietnam War. Prominent figures such as Martin Luther King Jr., Muhammad Ali, and Malcolm X spoke out against the war. King addressed a crowd of 3,000 people in New York City, criticising the war effort for sending young black men to fight in Southeast Asia while their rights were not protected at home. Ali, a champion boxer, risked his career and a prison sentence by resisting the draft in 1966. Malcolm X, Bob Moses, and other leaders of the Black Panther Party also became prominent opponents of the war, highlighting the racial and social injustices it perpetuated.

The anti-war movement also extended beyond public figures, with various organisations and groups forming to oppose the war. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) became the first major civil rights group to issue a formal statement against the war in 1965. The National Welfare Rights Organisation (NWRO), founded in 1967, critiqued the government's spending on the war instead of providing for families domestically. They emphasised the impact of the conflict on impoverished women and the prioritisation of military spending over human needs. These diverse voices united in challenging the constitutionality of the war and advocating for change.

US Navy's Iconic USS Constitution: How Many Ships Sunk?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$38 $40

$23.79 $29.99

Lawsuits against the President

The constitutionality of the Vietnam War was challenged in several lawsuits, with 26 of these cases reaching the Supreme Court. However, the Supreme Court never addressed the central constitutional question, resulting in what Texas Tech law professor Rodric B. Schoen termed a "strange silence". This silence effectively approved the government's war policies while refraining from explicit judicial endorsement.

One notable lawsuit against the President was filed by Velvel, a citizen who claimed that the invalid war had caused him harm by diverting funds from domestic programs, inflicting economic damage on businesses, and resulting in the conscription of his friends and relatives. The lawsuit was ultimately unsuccessful because the plaintiff could not demonstrate a personal injury caused by the war and was found to lack "standing".

Another case that reached the Supreme Court involved boxer Muhammad Ali, who challenged his draft evasion conviction. The Court overturned his conviction, ruling that the rejection of his conscientious objector claim was flawed. While this decision kept Ali out of the war, it did not address the broader constitutionality of the conflict.

In addition to lawsuits against the war itself, there have also been legal actions seeking redress for specific atrocities committed during the conflict. For example, in 2004, the Vietnam Association for Victims of Agent Orange (VAVA) filed a class-action lawsuit in a U.S. court against the producers of Agent Orange, a toxic herbicide used during the war. The case was dismissed in 2008, prompting criticism from the Vietnamese government, which argued that the verdict ignored the harm caused by Agent Orange.

Decades after the war, efforts at reconciliation between the United States and Vietnam have been impacted by policy decisions made by the Trump administration, such as the suspension of funding for demining operations and the proposed tariff on Vietnamese exports. These actions have complicated the process of addressing the legacies of the war and fostering cooperation between the two nations.

The US Constitution: A Founding Document's Name and Legacy

You may want to see also

Media portrayal of the war

The Vietnam War is often referred to as the "first television war". Television brought battles directly to American living rooms, and the media played an immense role in what the American people saw and believed. The number of journalists in Vietnam grew from fewer than two dozen in 1964 to about 600 of all nationalities in 1968, at the height of the war.

The media's portrayal of the war was a subject of controversy. Some believe that the media played a large role in the US defeat, with its tendency towards negative reporting undermining support for the war in the US, and its uncensored coverage providing valuable information to the enemy in Vietnam. However, many experts who have studied the media's role have concluded that, prior to 1968, most reporting was actually supportive of the US effort in Vietnam. The media was strongly anti-communist, and this bias was reflected in its coverage. For example, the label "the Vietnamese" was habitually applied to those fighting on the side of the French, not to those in the Viet Minh. The media also ignored the despotic tendencies of South Vietnam's president, Ngo Dinh Diem, instead highlighting his anti-communism.

The media's portrayal of the war began to change in 1968, with Walter Cronkite, anchor of the CBS Evening News, assessing that the conflict was "mired in stalemate". This was seen by many as a turning point in reporting about Vietnam and inspired President Lyndon B. Johnson to comment, "If I've lost Cronkite, I've lost Middle America". The increasingly negative tone of reporting may have reflected similar feelings among the American public. As the American commitment to the war waned, there was an increasing media emphasis on Vietnamization, the South Vietnamese government, and casualties – both American and Vietnamese. There was also more coverage of the collapse of morale, interracial tensions, drug abuse, and disciplinary problems among American troops.

The media's coverage of the Tet Offensive in January 1968 is often cited as a major turning point in media coverage of the war. While the offensive was a military failure for North Vietnam, the media focused on a few unfavourable combat actions and missed the "winning story of the big picture". As a result, the public viewed the offensive as a triumph for the communists and quickly changed their opinions against the war.

Foundations of Freedom: Guarding Tyranny with the Constitution

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, there were several challenges to the constitutionality of the Vietnam War. Most of these cases, however, involved challenges to the draft by those who had been called for duty, rather than a direct challenge to the war itself.

The Supreme Court never answered the core constitutional question, which created a legacy of "strange silence", according to Texas Tech law professor Rodric B. Schoen. This silence meant that the presidential power to start wars remained largely unchecked.

One notable case was brought by an individual named Velvel, who sued President Johnson on the claim that, as a citizen, he had been injured by the invalid war. He argued that the war had diverted money needed for domestic programs, caused economic harm to citizens running businesses, and summoned friends and relatives to serve in Vietnam. Ultimately, his lawsuit failed as he could not demonstrate that he had been personally injured by the war effort.