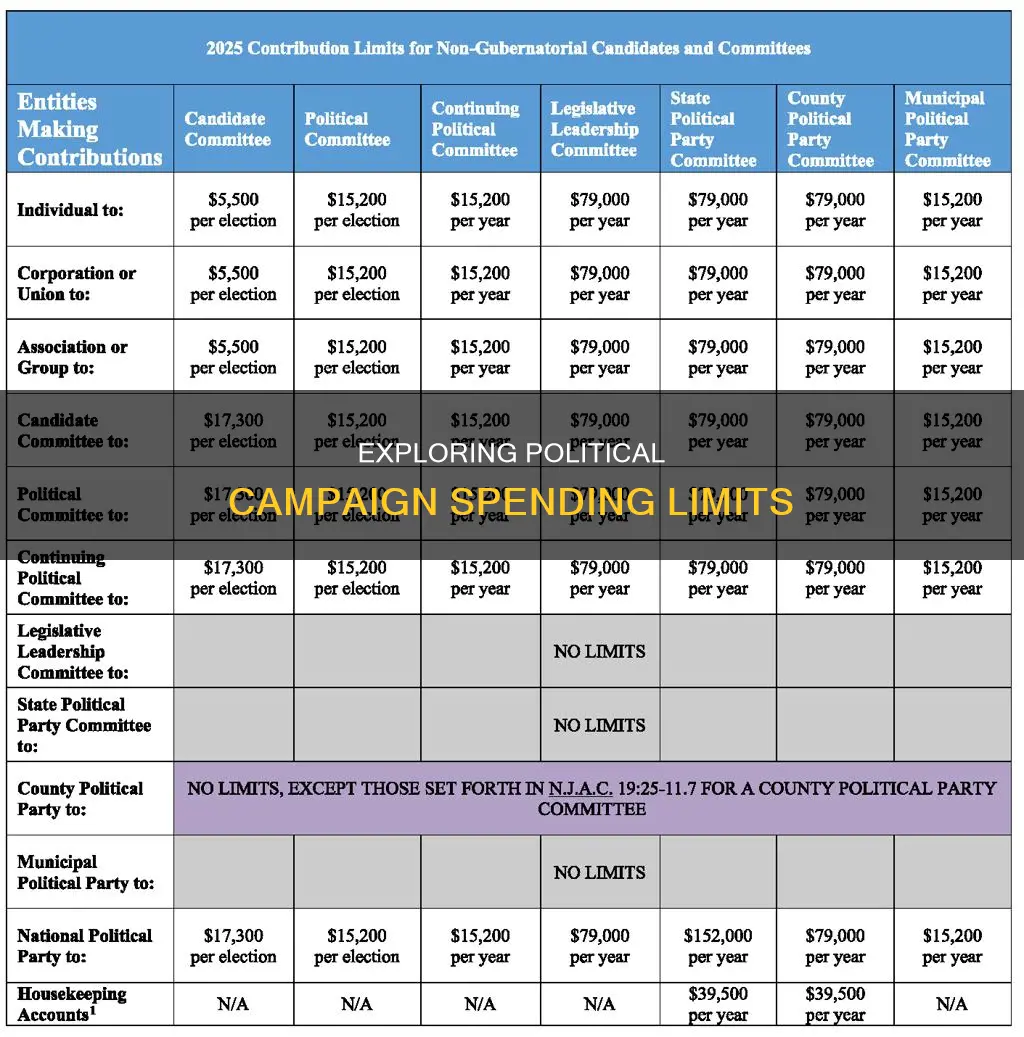

Political campaign spending is a highly contentious issue in the United States, with many Americans calling for limits on the amount of money individuals and organisations can contribute to campaigns. The Federal Election Commission (FEC) enforces the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (FECA), which limits the amount of money that can be donated to a candidate running for federal office. However, there are different rules for different types of organisations, and some loopholes have been identified, such as soft money spending, which is not subject to the same restrictions as direct contributions to specific candidates.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Limits on campaign spending | The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (FECA) limits the amount of money individuals and political organizations can give to a candidate running for federal office |

| Spending by candidates on their own campaigns | Candidates can spend their own personal funds on their campaign without limits but must report the amount they spend to the Federal Election Commission (FEC) |

| Contributions by individuals to multiple candidates | Individuals can donate to more than one candidate in each federal election |

| Accounting system for contributions | Campaigns must adopt an accounting system to distinguish between contributions made for the primary election and those made for the general election |

| Handling of excessive contributions | Campaigns are prohibited from retaining contributions that exceed the limits. In the event of excessive contributions, special procedures must be followed |

| Independent-expenditure-only political committees ("Super PACs") | May accept unlimited contributions, including from corporations and labor organizations |

| Limits on soft money | Following court rulings in Citizens United v. FEC and SpeechNOW.org v. FEC, soft money political spending is exempt from federal limits |

| Public support for limits on campaign spending | A majority of Americans, especially Democrats, support limits on campaign spending and believe new laws could reduce the role of money in politics |

| Disclosure of political spending | As of 2018, disclosure laws do not regulate political advertising on the internet, creating the potential for undisclosed online spending |

| Influence of big donors | Many Americans believe that big donors have more political influence than ordinary citizens and that limiting campaign spending could empower citizens to influence the government |

Explore related products

$20.67 $29.99

What You'll Learn

Public support for spending limits

There is extensive public support for spending limits on political campaigns. A Pew Research Center report from 2024 found that 72% of US adults believe there should be limits on the amount of money individuals and organizations can spend on political campaigns, with just 11% saying that individuals and organizations should be able to spend as much money as they want. This support for spending limits is bipartisan, with 71% of Republicans and 85% of Democrats supporting such limits.

The public is concerned about the influence of money in politics, with 74% saying it is very important that major political donors do not have more influence than others. This is reflected in the belief that campaign donors and lobbyists have too much influence on members of Congress, with 84% of the public holding this view. A further 73% say that lobbyists and special interest groups have too much influence. This is supported by the perception that political campaigns are too costly, with 85% of Americans agreeing that the cost of campaigns makes it difficult for good people to run for office.

The influence of money is also seen in the belief that elected officials are too responsive to donors and special interests, with members of Congress seen as unable or unwilling to separate their financial interests from their work. This is further evidenced by the perception that self-interest, especially the desire to make money, is one of the main reasons people run for office.

There is also a perception that new campaign finance laws could effectively reduce the role of money in politics, with 65% of the public holding this view. This is supported by proposals from reform groups, such as The Brennan Center, which has suggested encouraging "small donor public financing" by using public funds to match and multiply small donations.

Blocking Political Ads: Regaining Control Over Your Phone

You may want to see also

Unlimited contributions to super PACs

In the United States, there are limits to the amount of money individuals and political organisations can give to a candidate running for federal office. These limits are enforced by the Federal Election Commission (FEC) under the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (FECA).

However, these limits do not apply to independent-expenditure-only political committees, also known as "super PACs". Super PACs are permitted to accept unlimited contributions from individuals, corporations, labour organisations, and other political committees. They are also allowed to spend unlimited amounts of money on independent expenditures in federal races, such as advertisements that advocate for or against a specific candidate's election. It is important to note that super PACs cannot contribute directly to candidates or political party committees.

The legality of unlimited contributions to super PACs has been a subject of debate. Some argue that it provides an opportunity for secret spending groups, also known as "dark money groups", to funnel donations through super PACs, allowing the true sources of election spending to remain undisclosed. On the other hand, the Supreme Court in Citizens United v. FEC concluded that such independent spending could not be corrupting, and therefore permitted super PACs to accept unlimited contributions.

To address concerns about transparency, legislation such as the Democracy Is Strengthened by Casting Light on Spending in Elections (DISCLOSE) Act has been proposed. This draft bill aims to require organisations making political expenditures to disclose donors who have contributed significant amounts during an election cycle, providing voters with more information about the sources of campaign funding.

Who is Senator Walz? Age and Background Explored

You may want to see also

Hard money vs soft money

Campaign financing is essential to the success of political campaigns, allowing candidates to spread their message, connect with voters, and run effective advertisements. In the US, campaign funds are generally classified into two categories: hard money and soft money.

Hard money refers to contributions made directly to a candidate's campaign. For instance, if you were to give $50 directly to a candidate's campaign, that would be deemed a hard money donation. As hard money is contributed directly to a candidate, it is seen as an explicit endorsement of that person and their platform. Hard money can also refer to direct payments for services rendered, such as brokerage commissions.

Soft money refers to funds contributed to political parties or committees for "party-building activities" rather than to a specific candidate's campaign. For example, it is often used to support party-wide activities like voter registration or general "Get out the vote" efforts. Soft money contributions are not subject to the same FEC regulations as hard money. However, recent reforms, such as the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, have limited its influence, especially in federal elections. Soft money funds can be spent on activities that benefit a party or its general mission but cannot explicitly support or directly benefit a federal candidate. Soft money can also refer to payments for indirect items, such as providing free research to settle a costly error.

Soft money political spending was exempt from federal limits following the Citizens United v. FEC and SpeechNOW.org v. FEC court decisions in 2010, creating what some have called "a major loophole" in federal campaign financing and spending law. This led to the rise of "Super PACs", which can receive unlimited contributions from individuals, corporations, and other groups, and spend unlimited amounts of money to advocate for or against candidates or issues, provided there is no coordination with any campaign or candidate.

Campaign Issues: Understanding Political Promises and Problems

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Candidates' personal funds

The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (FECA) enforced by the Federal Election Commission (FEC) limits the amount of money individuals and political organisations can contribute to a candidate running for federal office. However, candidates can spend their own personal funds on their campaign without limits. Nevertheless, they must report the amount they spend to the FEC, and there are rules in place regarding what constitutes a candidate's personal funds.

A publicly funded presidential primary candidate must agree to limit their spending from their personal funds to $50,000. A contribution to a major party (Republican or Democratic) presidential general election campaign is prohibited if the candidate chooses to receive general election public funds. However, a person may contribute to a non-major party nominee who receives partial general election public financing up to the expenditure limits. The nominee must also agree to limit spending from personal funds to $50,000.

Designated contributions are recommended by the FEC to ensure that the contributor's intent is conveyed to the candidate's campaign. In the case of contributions from political committees, written designations also promote consistency in reporting and avoid the possible appearance of excessive contributions on reports. Campaigns must also adopt an accounting system to distinguish between contributions made for the primary election and those made for the general election.

There has been extensive criticism of the influence of money in politics in the United States, with some calling for the full disclosure of all political spending. Following court rulings such as Citizens United v. FEC, reformers have suggested encouraging "small donor public financing", using public funds to match and multiply small donations.

Kamala's Path to Victory: What are the Odds?

You may want to see also

Dark money groups

Dark money refers to political spending meant to influence voters' decisions without disclosing the donor or the source of the money. This kind of spending is typically associated with funds spent by political nonprofits or super PACs. Dark money groups are outside groups that are not political parties and can accept unlimited sums of money from individuals, corporations, or unions. They may engage in direct political activities, including advertising that advocates for or against a candidate, going door-to-door, or running phone banks.

The Citizens United v. FEC court decision created loopholes in campaign disclosure rules, making dark money common. Powerful groups have funnelled over $1 billion into federal elections since 2010, often targeting competitive races. This lack of transparency makes it challenging for voters to make informed decisions, as they are unaware of who is trying to influence them.

Examples of dark money groups include the 45Committee, the 60 Plus Association, VoteVets Action Fund, and American Encore. These groups have raised significant funds, with the 45Committee bringing in $49 million between April 2015 and March 2017, and the 60 Plus Association raising $92 million between July 2009 and June 2017. VoteVets Action Fund, affiliated with the VoteVets super PAC, collects contributions from individuals, corporations, and labour unions, with labour unions accounting for about $1 of every $8 raised between July 2009 and June 2017.

Block Texts: Stop Democratic Consultants' Spam

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, there are limits to how much money individuals and political organisations can contribute to a political campaign. These limits are enforced by the Federal Election Commission (FEC) in the US. However, candidates can spend unlimited amounts of their own personal funds on their campaigns.

The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (FECA) enforces limits on campaign spending. The FEC updates contribution limits every two years, adjusting them for inflation. The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) increased the contribution limits for individuals giving to federal candidates and political parties.

Yes, following the Supreme Court's 2010 decision in Citizens United v. FEC, soft money political spending was made exempt from federal limits. Independent-expenditure-only political committees, or "Super PACs", can accept unlimited contributions, including from corporations and labour organisations.