The question of whether political parties are decentralized and fragmented is a critical one in contemporary political discourse, as it directly impacts their ability to govern effectively, represent diverse interests, and maintain internal cohesion. Decentralization within parties often reflects efforts to empower local chapters or factions, allowing for greater responsiveness to regional or ideological concerns, but it can also lead to internal divisions and inconsistent messaging. Fragmentation, on the other hand, arises when parties splinter into competing groups or lose a unified vision, often driven by ideological polarization, leadership disputes, or shifting voter demographics. These dynamics are particularly evident in multi-party systems or during periods of political upheaval, where parties struggle to balance unity with inclusivity. Analyzing these trends is essential for understanding how political parties adapt to changing societal demands and whether such changes strengthen or undermine democratic institutions.

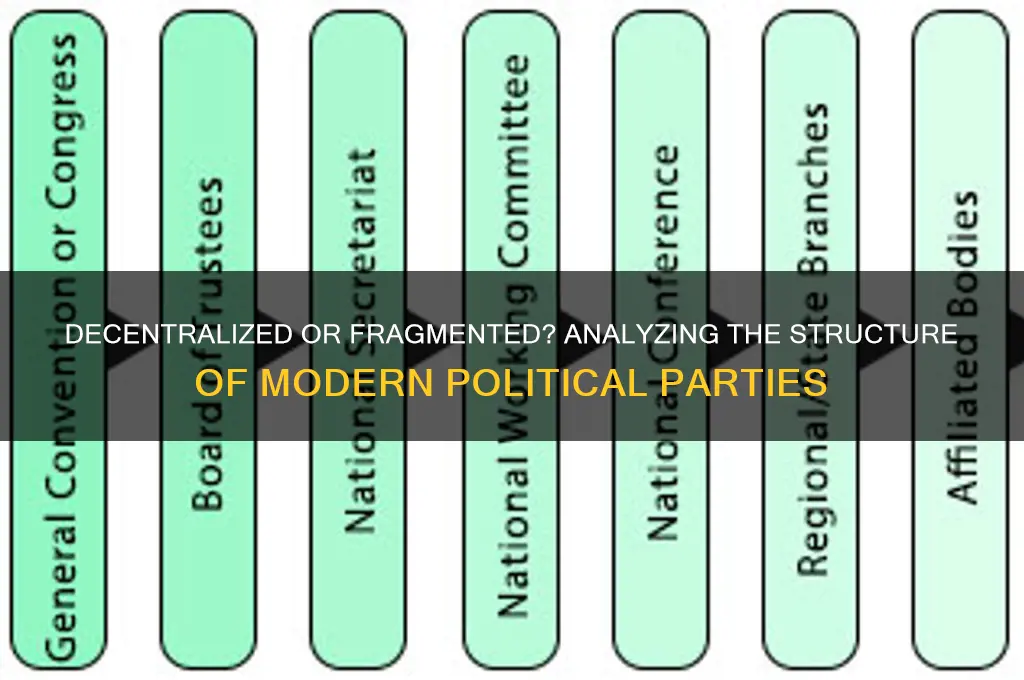

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Decentralization | Varies by party and country; some parties have strong central leadership, while others distribute power regionally or locally. |

| Fragmentation | Increasing trend globally, with more splinter groups and smaller parties emerging due to ideological differences or regional interests. |

| Decision-Making | Decentralized parties often involve local chapters in policy decisions, while centralized parties rely on national leadership. |

| Funding Sources | Fragmented parties may rely on diverse, smaller donors, whereas centralized parties often have larger, more consolidated funding streams. |

| Membership Structure | Decentralized parties typically have a broader, more dispersed membership base, while fragmented parties may have niche or localized support. |

| Policy Cohesion | Centralized parties generally maintain consistent policy platforms, whereas fragmented parties may exhibit internal policy disagreements. |

| Leadership Dynamics | Decentralized parties often have multiple power centers, while fragmented parties may struggle with unified leadership. |

| Electoral Performance | Fragmentation can lead to vote splitting, while decentralization may improve local appeal but weaken national coordination. |

| Internal Democracy | Decentralized parties often have more participatory internal processes, while centralized parties may prioritize efficiency over inclusivity. |

| Adaptability | Decentralized and fragmented parties can be more responsive to local issues but may lack the cohesion needed for national-level governance. |

Explore related products

$1.99 $21.95

What You'll Learn

Impact of decentralization on party cohesion

Decentralization within political parties can significantly impact party cohesion, often leading to both positive and negative outcomes. When a party adopts a decentralized structure, decision-making authority is distributed across various regional or local branches, reducing the dominance of a central leadership. This distribution of power can foster greater inclusivity and responsiveness to local needs, as regional leaders are more attuned to the specific concerns of their constituencies. However, this very dispersion of authority can also dilute the party’s central message and policy direction, making it harder to maintain a unified stance on national or global issues. As a result, decentralized parties may struggle to present a coherent platform, which can undermine their credibility and effectiveness in elections or legislative processes.

One of the most direct impacts of decentralization on party cohesion is the emergence of internal factions or splinter groups. When local or regional branches gain autonomy, they may prioritize their interests over the party’s broader goals, leading to ideological or strategic divergences. These fractures can escalate into public disputes, weakening the party’s public image and eroding trust among voters. For instance, in decentralized parties, progressive and conservative wings might clash over key policies, such as taxation or social welfare, creating an appearance of disunity that opponents can exploit. Such fragmentation can also hinder the party’s ability to negotiate internally, making it difficult to reach consensus on critical issues.

On the other hand, decentralization can enhance party cohesion by empowering grassroots members and fostering a sense of ownership among local leaders. When regional branches have a say in decision-making, they are more likely to feel invested in the party’s success, which can boost morale and participation. This bottom-up approach can also lead to more innovative and context-specific solutions, as local leaders are better positioned to address unique challenges. However, this benefit hinges on effective communication and coordination mechanisms between the central leadership and regional branches. Without such mechanisms, decentralization can exacerbate fragmentation rather than strengthen cohesion.

Another critical impact of decentralization is its effect on party discipline and accountability. In centralized parties, the leadership can enforce strict adherence to the party line, ensuring that members vote or act in unison. Decentralized parties, however, often lack such enforcement mechanisms, allowing individual members or branches to deviate from the party’s official stance. While this flexibility can be a strength in diverse societies, it can also lead to inconsistency and unpredictability, particularly in legislative bodies. For example, decentralized parties may struggle to whip votes on critical bills, as regional representatives prioritize local interests over party loyalty.

In conclusion, the impact of decentralization on party cohesion is complex and multifaceted. While it can promote inclusivity, innovation, and grassroots engagement, it also risks fostering fragmentation, ideological divergence, and disciplinary challenges. The success of decentralization in maintaining party cohesion depends largely on the party’s ability to balance autonomy with coordination, ensuring that regional branches remain aligned with the central vision while addressing local needs. Parties that fail to strike this balance may find themselves weakened by internal divisions, while those that succeed can harness the strengths of decentralization to build a more resilient and responsive organization.

Are Political Parties Companies? Exploring the Corporate Nature of Politics

You may want to see also

Fragmentation in multi-party political systems

One of the primary drivers of fragmentation is the decentralization of political power. In multi-party systems, power is often dispersed across numerous parties, each representing specific constituencies or ideologies. This decentralization can empower marginalized groups by giving them a voice in the political process, but it can also lead to instability. When no party holds a dominant position, coalition governments become the norm. While coalitions can foster inclusivity and compromise, they are often fragile and prone to collapse due to conflicting interests among coalition partners. This instability can undermine policy consistency and long-term planning, as governments may prioritize short-term political survival over sustained reforms.

Ideological polarization further exacerbates fragmentation. As societies become more diverse and complex, political parties may splinter into smaller factions over disagreements on key issues such as economic policy, social justice, or environmental concerns. For instance, a left-wing party might fragment into socialist, green, and social democratic factions, each with distinct priorities. This ideological fragmentation can make it difficult for parties to unite even when they share broad ideological alignments, as seen in countries like Belgium or Israel, where deep ideological and cultural divides have led to chronic political stalemates.

Regional and ethnic divisions also play a significant role in fragmentation. In multi-party systems, regional parties often emerge to advocate for the specific interests of particular areas, which may be overlooked by national parties. While these parties can effectively represent local concerns, they can also contribute to fragmentation by prioritizing regional agendas over national unity. For example, in India, regional parties have gained prominence by championing state-specific issues, but their rise has made it harder for national parties to form stable governments without complex coalitions.

Finally, electoral systems can either mitigate or amplify fragmentation. Proportional representation systems, which allocate parliamentary seats based on the percentage of votes received, tend to encourage multi-party systems and fragmentation by allowing smaller parties to gain representation. In contrast, majoritarian or first-past-the-post systems favor larger parties and can reduce fragmentation by discouraging smaller parties from competing. However, even within proportional systems, thresholds for parliamentary representation can be implemented to limit the number of small parties, as seen in countries like Germany or New Zealand.

In conclusion, fragmentation in multi-party political systems is a complex and multifaceted issue, driven by decentralization, ideological polarization, regional divisions, and electoral mechanisms. While fragmentation can enhance representation and inclusivity, it also poses challenges to governance stability and policy coherence. Understanding and managing these dynamics is crucial for maintaining effective democratic functioning in multi-party systems.

Interest Groups vs. Political Parties: Which Holds More Power in Politics?

You may want to see also

Role of regional interests in party structure

The role of regional interests in shaping party structure is a critical factor in understanding the decentralization and fragmentation of political parties. Regional interests often reflect distinct cultural, economic, and social priorities that may not align with national agendas. As a result, political parties frequently adapt their organizational frameworks to accommodate these regional demands, leading to decentralized structures. In federal systems, such as those in India, Germany, or the United States, regional parties emerge as powerful entities, often rivaling or even surpassing national parties in their respective states or regions. These regional parties advocate for localized issues, ensuring that their specific interests are represented in broader political discourse. This dynamic forces national parties to either decentralize their decision-making processes or risk losing relevance in key regions.

Regional interests also contribute to fragmentation within political parties by fostering internal divisions based on geography. Within a single party, regional factions may develop distinct ideologies, policy preferences, or leadership styles to better address local concerns. For instance, in countries like Italy or Spain, regional branches of national parties often operate with significant autonomy, allowing them to tailor their platforms to regional electorates. This autonomy can lead to conflicts between the national leadership and regional branches, particularly when national policies are perceived as detrimental to regional interests. Such fragmentation weakens party cohesion and complicates the implementation of unified strategies, further decentralizing the party structure.

The influence of regional interests on party structure is also evident in the allocation of resources and power within parties. Regional strongholds often command disproportionate influence in party decision-making, as they contribute significantly to electoral success. This power imbalance can marginalize other regions or factions within the party, exacerbating internal tensions. For example, in Brazil, the Workers' Party (PT) has historically relied on its strongholds in the Northeast, which has shaped its policy priorities and leadership dynamics. Similarly, in Canada, the Conservative Party's regional base in the West often clashes with its more moderate factions in Ontario and Quebec. This regional dominance within parties underscores the fragmented nature of their internal power structures.

Moreover, regional interests drive the formation of coalitions and alliances that further decentralize party systems. In countries with diverse regional identities, such as Belgium or Switzerland, parties often form coalitions based on regional affiliations rather than ideological alignment. These coalitions are essential for governing but can dilute the ideological coherence of individual parties, leading to fragmentation. Regional parties in such systems may prioritize their local agendas over national unity, making it challenging for central authorities to maintain control. This regional-centric approach to politics reinforces the decentralized nature of party structures and highlights the enduring influence of regional interests.

In conclusion, regional interests play a pivotal role in shaping the decentralized and fragmented nature of political parties. By advocating for localized priorities, fostering internal divisions, influencing resource allocation, and driving coalition-building, regional interests compel parties to adopt flexible and often fragmented structures. This adaptability, while essential for representing diverse populations, can also undermine party cohesion and complicate governance. Understanding the interplay between regional interests and party structure is therefore crucial for analyzing the broader trends of decentralization and fragmentation in contemporary political systems.

Are Political Parties Constitutional? Exploring Their Legal and Historical Basis

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Effects of internal party democracy on unity

Internal party democracy, which refers to the degree to which decision-making power is distributed among party members rather than concentrated in the hands of a few leaders, has significant effects on party unity. When political parties embrace internal democracy, they often experience both positive and negative consequences for their cohesion. On the positive side, internal democracy can foster a sense of ownership and engagement among party members, as they feel their voices are heard and their contributions matter. This inclusivity can strengthen unity by aligning members around shared goals and values, reducing feelings of alienation or marginalization. For instance, when grassroots members participate in candidate selection or policy formulation, they are more likely to support the party’s decisions, even if they do not fully align with their personal preferences.

However, internal party democracy can also lead to fragmentation if not managed carefully. Decentralized decision-making processes often amplify ideological and personal differences within the party, as various factions push for their agendas. This can result in public disagreements, leadership contests, or even splits, particularly in parties with diverse membership bases. For example, in parties where left-wing and centrist factions coexist, internal democracy may provide a platform for these groups to openly challenge each other, potentially undermining unity. The challenge lies in balancing the benefits of inclusivity with the need for a cohesive party structure that can function effectively in competitive political environments.

Another effect of internal party democracy on unity is its impact on leadership stability. When power is decentralized, leaders may face greater scrutiny and challenges from within the party. While this can prevent authoritarianism and ensure accountability, it can also lead to frequent leadership changes or weakened authority, both of which can destabilize the party. A party with a revolving-door leadership is less likely to present a unified front to the public, as constant internal struggles overshadow its policy agenda. Conversely, parties with strong internal democratic mechanisms but clear rules for leadership transitions may maintain unity by ensuring that power shifts are orderly and accepted by all factions.

Internal democracy also influences how parties respond to external challenges, such as electoral setbacks or policy failures. Parties with robust internal democratic processes are often better equipped to engage in self-reflection and adapt to changing circumstances, which can strengthen unity in the long term. For instance, after an electoral defeat, a party with internal democracy might engage in open debates to identify mistakes and chart a new course, involving members at all levels. This collective approach can rebuild morale and unity. In contrast, parties with centralized structures may suppress dissent, leading to simmering discontent and eventual fragmentation.

Finally, the effects of internal party democracy on unity depend heavily on the broader political and cultural context. In societies with strong traditions of participatory politics, internal democracy is more likely to enhance unity by aligning with societal norms. However, in contexts where political parties are historically centralized and hierarchical, attempts to introduce internal democracy may initially cause friction and division. For example, parties in transitioning democracies may struggle to balance the demands of internal democracy with the need for strong leadership to navigate unstable political landscapes. Ultimately, the success of internal party democracy in fostering unity hinges on its implementation, the party’s ability to manage diversity, and the external environment in which it operates.

Political Parties: Essential for Democracy or Divisive Forces?

You may want to see also

Influence of external funding on decentralization

The influence of external funding on the decentralization of political parties is a critical aspect of understanding their organizational structure and decision-making processes. External funding, often sourced from donors, corporations, or international entities, can significantly shape how power is distributed within a party. When a political party relies heavily on external funding, it may become centralized around a small group of individuals or committees responsible for managing these resources. This centralization occurs because the control of funds often translates to control over strategic decisions, candidate nominations, and policy priorities. As a result, local chapters or grassroots members may have limited autonomy, reducing the overall decentralization of the party.

However, external funding can also paradoxically promote decentralization under certain conditions. For instance, if external donors prioritize supporting local initiatives or grassroots movements, they may provide resources directly to regional or district-level party units. This direct funding can empower local leaders and members, allowing them to operate with greater independence from the central party leadership. In such cases, external funding acts as a decentralizing force by bypassing the central hierarchy and fostering localized decision-making. The key factor here is the donor’s intent and the mechanisms through which funds are distributed.

The nature of external funding—whether it is conditional or unconditional—also plays a pivotal role in determining its impact on decentralization. Conditional funding, tied to specific goals or policies, often reinforces centralization because it requires alignment with the priorities of the funding entity. This can lead to a top-down approach where the central leadership ensures compliance with donor conditions. In contrast, unconditional funding provides greater flexibility to local units, enabling them to allocate resources based on regional needs and priorities. This flexibility can enhance decentralization by allowing diverse voices within the party to influence its direction.

Moreover, the source of external funding can introduce fragmentation within political parties, particularly when different factions or wings secure funding from competing or ideologically divergent donors. For example, if one faction receives funding from progressive international organizations while another is supported by conservative domestic donors, the party may become internally divided. This fragmentation can lead to a decentralized structure, but it is often characterized by conflict rather than cohesion. Such scenarios highlight how external funding can inadvertently contribute to both decentralization and internal discord within parties.

In conclusion, the influence of external funding on decentralization is complex and depends on factors such as the distribution mechanisms, conditions attached to the funding, and the sources of the funds. While external funding can centralize power by concentrating resource control in the hands of a few, it can also decentralize authority when directed toward local units or provided unconditionally. Additionally, the diversity of funding sources can lead to fragmentation, further complicating the party’s organizational dynamics. Understanding these nuances is essential for analyzing whether political parties are decentralized or fragmented in the context of external financial influences.

Are PACS Integral Components of Political Party Structures?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political parties vary in their level of decentralization. Some parties, particularly in federal systems, may have decentralized structures where local or regional branches retain significant autonomy. Others, especially in centralized systems, are more hierarchical with decision-making concentrated at the national level.

Fragmentation in political parties often arises from internal divisions over ideology, leadership, or policy priorities. External factors like electoral systems, societal polarization, and the rise of niche or single-issue movements can also contribute to fragmentation.

Decentralized and fragmented parties can face challenges in maintaining unity and coherence, which may hinder effective governance. However, they can also be more responsive to diverse local needs and interests, potentially fostering inclusivity and adaptability in policymaking.