The question of whether political opinions qualify as personal data is a complex and increasingly relevant issue in the digital age. As data protection laws, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union, define personal data broadly to include any information relating to an identifiable individual, political opinions fall into a gray area. On one hand, political beliefs are deeply personal and can reveal significant aspects of an individual’s identity, making them sensitive data deserving of heightened protection. On the other hand, the public expression of political views, such as through social media or voting records, complicates their classification, as they may be considered publicly available information. This debate intersects with concerns about privacy, free speech, and the potential for misuse of such data by governments, corporations, or other entities, raising critical questions about how societies should balance individual rights with the realities of data collection and analysis in the modern world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Political opinions are considered a special category of personal data under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union. |

| Legal Classification | Classified as "sensitive personal data" under GDPR Article 9, requiring explicit consent for processing. |

| Protection Level | High protection due to potential risks of discrimination, profiling, or harm. |

| Processing Requirements | Explicit consent, substantial public interest, or legal obligations are necessary for lawful processing. |

| Global Variations | Laws differ by jurisdiction; e.g., GDPR (EU) vs. CCPA (California) where political opinions are not explicitly categorized as sensitive. |

| Data Sensitivity | Highly sensitive due to potential impact on individual rights and freedoms. |

| Examples of Data | Voting records, party memberships, campaign donations, social media posts expressing political views. |

| Risks of Misuse | Profiling, discrimination, manipulation, or suppression of political rights. |

| Compliance Challenges | Ensuring lawful basis for processing, obtaining explicit consent, and safeguarding against unauthorized use. |

| Relevant Legislation | GDPR (EU), CCPA (California), other regional data protection laws. |

Explore related products

$11.06 $20

What You'll Learn

- Definition of personal data under GDPR and its applicability to political opinions

- How political opinions are collected, processed, and stored by organizations?

- Legal protections for political opinions as sensitive data under data protection laws

- Risks of profiling and discrimination based on inferred political beliefs

- Ethical considerations in using political opinions for targeted advertising or campaigns

Definition of personal data under GDPR and its applicability to political opinions

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) defines personal data as any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person. This broad definition encompasses a wide range of data types, from basic identifiers like names and addresses to more sensitive categories such as health information and biometric data. Political opinions, though not explicitly listed in the special categories of data under Article 9, fall under the umbrella of personal data due to their intrinsic link to an individual's identity and beliefs. This classification is crucial because it triggers the stringent protections afforded by the GDPR, ensuring that such data is processed lawfully, fairly, and transparently.

To determine the applicability of GDPR to political opinions, consider the context in which such data is collected and processed. For instance, if a political party gathers voter preferences through surveys or social media analytics, this information is clearly personal data. The processing must adhere to GDPR principles, including obtaining explicit consent, ensuring data minimization, and providing individuals with rights to access, rectify, or erase their data. Failure to comply can result in significant fines, up to €20 million or 4% of annual global turnover, whichever is higher. This underscores the importance of treating political opinions with the same care as other personal data.

A comparative analysis reveals that while political opinions are not treated as "sensitive" under GDPR, they share similarities with other protected data types. For example, like religious beliefs or trade union membership, political opinions reflect deeply held personal values. However, unlike sensitive data, political opinions do not require additional safeguards such as explicit consent for processing. This distinction highlights the GDPR’s nuanced approach, balancing the need for protection with the practicalities of data processing in democratic societies. Organizations must therefore navigate this gray area carefully, ensuring respect for individual rights without overburdening legitimate activities like political campaigning.

In practice, organizations handling political opinions should adopt a proactive compliance strategy. Start by conducting a data protection impact assessment (DPIA) to identify risks associated with processing such data. Implement robust consent mechanisms, even if not strictly required, to build trust with data subjects. Regularly train staff on GDPR requirements and the sensitivity of political data. Finally, establish clear procedures for responding to data subject requests, such as access or erasure, to ensure compliance and mitigate legal risks. By treating political opinions as personal data with heightened care, organizations can uphold both legal obligations and ethical standards.

Unveiling Political Artefacts: Exploring Tangible Symbols of Power and Ideology

You may want to see also

How political opinions are collected, processed, and stored by organizations

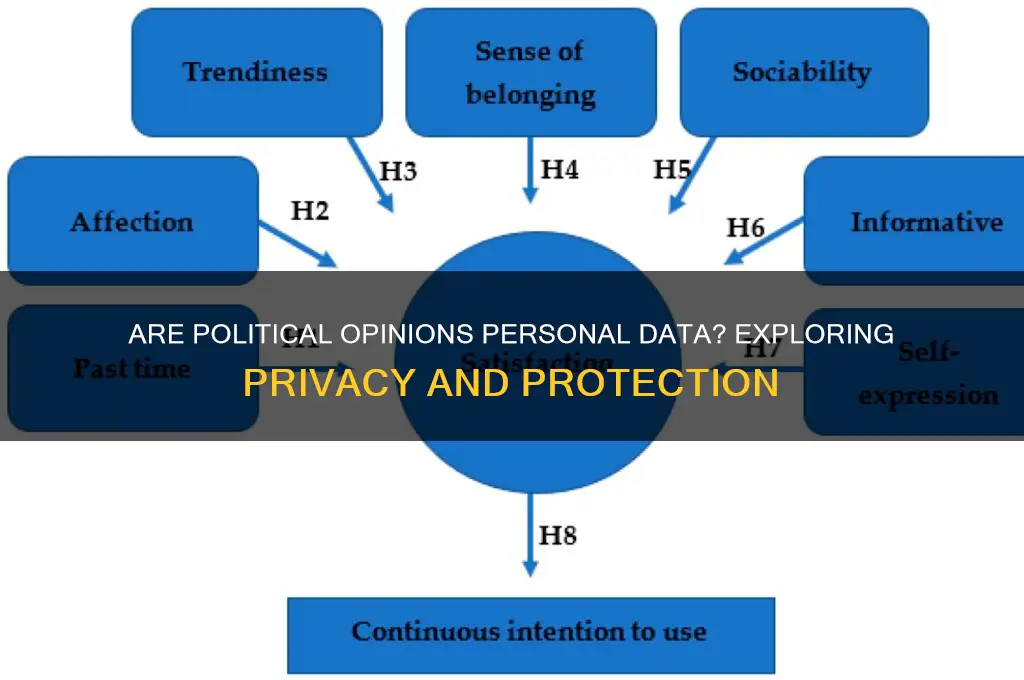

Political opinions are often inferred through a mosaic of data points rather than explicitly collected. Organizations leverage algorithms to analyze social media activity, online purchases, and even geolocation data to predict political leanings. For instance, a user who frequently engages with climate change content or purchases eco-friendly products might be categorized as leaning towards progressive policies. This indirect method of collection raises ethical questions about consent and transparency, as individuals may not realize their data is being used to profile their political beliefs.

Once collected, this data undergoes processing to extract meaningful insights. Machine learning models identify patterns and correlations, such as linking membership in certain online groups to specific political ideologies. For example, participation in gun rights forums could signal conservative tendencies. The processed data is then categorized and scored, often on a spectrum, to create detailed political profiles. These profiles are valuable for targeted advertising, fundraising, or even influencing voter behavior. However, the accuracy of these predictions is not always reliable, leading to potential misclassification and unintended consequences.

Storage of political opinion data is a critical yet often overlooked aspect. Organizations typically store this information in large databases, sometimes alongside other personal data like names, addresses, and contact details. The retention period varies, with some entities keeping data indefinitely for future analysis. This long-term storage poses significant risks, including data breaches that could expose sensitive political affiliations. For instance, a leak of such data could lead to discrimination or harassment, particularly in polarized societies.

To mitigate risks, regulatory frameworks like the GDPR in Europe classify political opinions as sensitive personal data, imposing stricter rules on their handling. Organizations must ensure lawful processing, often requiring explicit consent. However, enforcement remains a challenge, especially with global data flows. Practically, individuals can protect themselves by auditing their online presence, limiting data sharing, and using privacy tools like VPNs. Organizations, meanwhile, should adopt ethical data practices, including regular audits and transparent policies, to build trust and comply with evolving regulations.

Inequality's Grip: How Economic Disparity Fuels Political Instability

You may want to see also

Legal protections for political opinions as sensitive data under data protection laws

Political opinions are increasingly recognized as sensitive personal data under data protection laws, warranting heightened legal safeguards. This classification stems from their potential to expose individuals to discrimination, harassment, or harm if misused. For instance, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) explicitly categorizes political opinions as a special category of personal data, subject to stricter processing conditions. Similarly, laws in jurisdictions like Canada and Brazil impose limitations on collecting and processing such data without explicit consent. These protections reflect a global acknowledgment of the intimate and potentially vulnerable nature of political beliefs.

To ensure compliance, organizations must adhere to specific steps when handling political opinion data. First, they must obtain explicit consent from individuals, clearly explaining the purpose and scope of data collection. Second, they should implement robust security measures to prevent unauthorized access or breaches. Third, data retention periods must be strictly defined, ensuring information is not stored indefinitely. For example, a political campaign collecting voter preferences must delete this data after the election cycle unless individuals consent to further use. Failure to comply can result in severe penalties, such as GDPR fines of up to €20 million or 4% of annual global turnover.

A comparative analysis reveals variations in how countries protect political opinion data. While the GDPR provides a comprehensive framework, the United States lacks a federal law specifically addressing political opinions as sensitive data. Instead, protections are piecemeal, relying on sector-specific regulations like the Federal Election Campaign Act. In contrast, India’s Personal Data Protection Bill (2023) proposes classifying political opinions as sensitive, aligning more closely with European standards. These differences highlight the need for global harmonization to ensure consistent protections across borders, especially as political data increasingly flows internationally.

Practically, individuals must be proactive in safeguarding their political opinions. Regularly reviewing privacy settings on social media platforms, avoiding public disclosure of sensitive beliefs, and using encrypted communication tools are effective measures. For instance, tools like Signal or ProtonMail can protect private discussions about political views. Additionally, individuals should exercise caution when participating in online polls or surveys, ensuring the collector is reputable and compliant with data protection laws. Awareness of one’s rights under relevant legislation empowers individuals to challenge misuse of their political data.

In conclusion, legal protections for political opinions as sensitive data are critical in an era of digital surveillance and data exploitation. Organizations must navigate strict compliance requirements, while individuals need to adopt proactive measures to safeguard their beliefs. As data protection laws evolve, the classification of political opinions as sensitive data underscores a broader commitment to preserving privacy and freedom of expression in democratic societies.

Are Political Commentary Opinion Pieces Shaping Public Perception?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Risks of profiling and discrimination based on inferred political beliefs

Political opinions, whether explicitly shared or inferred, are increasingly treated as personal data in the digital age. This classification raises significant concerns about profiling and discrimination, as algorithms and data brokers seek to categorize individuals based on their perceived beliefs. The risks are not hypothetical; they manifest in real-world consequences, from targeted misinformation campaigns to biased employment opportunities. Understanding these dangers is the first step toward mitigating them.

Consider the mechanics of inference: algorithms analyze online behavior—likes, shares, comments, even browsing patterns—to predict political leanings. This process is often opaque, leaving individuals unaware of how their beliefs are being interpreted or used. For instance, a person who frequently engages with environmental content might be labeled as a "green activist," a profile that could influence the ads they see, the news they receive, or even their insurance premiums. The problem lies in the accuracy and fairness of these inferences. Algorithms can misclassify individuals, leading to discrimination based on mistaken assumptions. A casual interest in political debates might be misinterpreted as staunch advocacy, with disproportionate consequences.

The risks extend beyond individual harm to societal fragmentation. When political profiling is used to tailor content, it reinforces echo chambers, polarizing communities and stifling dialogue. For example, social media platforms might prioritize showing conservative users content that aligns with their inferred beliefs, while liberal users see a different reality. This segmentation undermines democratic discourse by limiting exposure to diverse viewpoints. Over time, such practices can erode trust in institutions and fuel extremism, as individuals are increasingly isolated within ideological bubbles.

To combat these risks, practical steps are essential. First, transparency in data processing is critical. Companies must disclose how political inferences are made and used, allowing individuals to challenge inaccuracies. Second, regulatory frameworks like the GDPR should be enforced rigorously, treating political opinions as sensitive data deserving of heightened protection. Finally, individuals can take proactive measures, such as using privacy tools to limit tracking and diversifying their online engagement to avoid algorithmic pigeonholing. While these steps won’t eliminate the risks entirely, they offer a starting point for reclaiming control over personal data and its implications.

Exploring the Diverse Political Divisions Across the Globe

You may want to see also

Ethical considerations in using political opinions for targeted advertising or campaigns

Political opinions, often considered deeply personal, are increasingly treated as valuable commodities in the digital advertising ecosystem. As platforms collect and analyze user data to tailor content, the ethical implications of leveraging political beliefs for targeted campaigns demand scrutiny. Unlike purchasing habits or location data, political views are inherently tied to identity and values, raising questions about consent, privacy, and manipulation. When advertisers exploit this data, they risk not only eroding trust but also amplifying societal divisions.

Consider the mechanics of such targeting: algorithms categorize users based on engagement with political content, donations to campaigns, or participation in online forums. This profiling enables hyper-specific messaging, often designed to reinforce existing beliefs rather than encourage dialogue. For instance, a voter identified as leaning left might be bombarded with ads warning of right-wing policies, while another receives messages stoking fears of progressive agendas. This echo chamber effect, while effective for engagement, undermines democratic discourse by polarizing audiences.

Ethical advertising in this context requires transparency and restraint. Platforms must clearly disclose how political opinions are collected and used, ensuring users understand the implications of their data being weaponized for persuasion. A practical step would be implementing opt-out mechanisms for political targeting, similar to those mandated for sensitive data like health information. Additionally, advertisers should adopt a "do no harm" principle, avoiding campaigns that exploit fear or misinformation to sway opinions.

Regulators also play a critical role in setting boundaries. Laws like the GDPR in Europe classify political opinions as sensitive personal data, requiring explicit consent for processing. Such frameworks provide a model for balancing innovation with individual rights. In the U.S., where regulations are less stringent, industry self-regulation has proven inadequate, highlighting the need for legislative intervention. Without robust oversight, the unchecked use of political data risks becoming a tool for manipulation rather than informed engagement.

Ultimately, the ethical use of political opinions in advertising hinges on respect for autonomy and the public good. While targeted campaigns can mobilize voters and foster participation, they must prioritize honesty and inclusivity over exploitation. Advertisers and platforms that fail to uphold these standards risk not only reputational damage but also contributing to the erosion of democratic norms. In an era of deepening polarization, the stakes could hardly be higher.

How Political Campaigns Mastered Strategy to Achieve Success

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, political opinions are generally classified as personal data under regulations like the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) in the EU, as they fall under the category of "special categories of personal data," which require additional protections.

No, collecting and processing political opinions typically requires explicit consent from the individual, as they are considered sensitive data. Organizations must also have a lawful basis and ensure the data is handled securely.

Sharing political opinions online can expose you to risks such as profiling, targeted advertising, or even discrimination. This data can be collected by third parties and used in ways you may not anticipate or consent to.

To protect your political opinions, be cautious about sharing them on public platforms, review privacy settings, and avoid providing such information unless necessary. You can also exercise your rights under data protection laws, such as requesting access or deletion of your data.