The United States Constitution, a foundational document outlining the framework of the federal government, does not explicitly mention interest groups or political parties. Drafted in 1787, the Constitution focuses on establishing the structure and powers of the three branches of government, delineating individual rights, and defining the relationship between the federal government and the states. Interest groups and political parties, which play significant roles in modern American politics, emerged and evolved outside the constitutional framework. While the First Amendment guarantees freedoms of speech, assembly, and petition, which are essential for the functioning of interest groups and political parties, these entities are not formally recognized or regulated within the Constitution itself. This omission reflects the Founding Fathers' initial skepticism of factions and party politics, as articulated in writings like the Federalist Papers, yet their development has become integral to the nation's political landscape.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Mention in the U.S. Constitution | Neither interest groups nor political parties are explicitly mentioned. |

| Role in Governance | Interest groups advocate for specific issues; political parties organize for electoral purposes. |

| Historical Context | Political parties emerged after the Constitution (e.g., Federalists, Anti-Federalists). Interest groups developed later. |

| Legal Recognition | Interest groups operate under First Amendment rights (freedom of assembly, speech, petition). Political parties are recognized through state laws and FEC regulations. |

| Constitutional Framework | The Constitution focuses on governmental structure, not on interest groups or political parties. |

| Influence on Policy | Both influence policy, but interest groups lobby for specific causes, while parties seek broader political control. |

| Funding and Regulation | Interest groups are regulated under lobbying laws. Political parties are regulated by campaign finance laws (e.g., FEC). |

| Constitutional Amendments | No amendments directly address interest groups or political parties. |

| Judicial Interpretation | Courts have upheld the role of both through interpretations of constitutional rights (e.g., Citizens United v. FEC for political parties and interest groups). |

| Public Perception | Both are seen as integral to American democracy, despite not being in the Constitution. |

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

What You'll Learn

Interest Groups vs. Political Parties: Constitutional Recognition

The U.S. Constitution, the foundational document of American governance, outlines the structure and powers of the federal government, but it does not explicitly mention either interest groups or political parties. This omission raises questions about their constitutional recognition and role in the political system. While both entities are integral to modern American politics, their status and influence derive from interpretations of constitutional principles, historical developments, and legal precedents rather than direct textual references.

Political parties, despite their absence from the Constitution, have become a cornerstone of the American political system. The Founding Fathers, such as George Washington, initially warned against the dangers of partisanship in the *Farewell Address*. However, the emergence of political parties, like the Federalists and Anti-Federalists, occurred almost immediately after the Constitution’s ratification. The Constitution’s structure, particularly the separation of powers and federalism, inadvertently created spaces for parties to organize and compete for influence. The First Amendment’s protections of free speech and assembly further enabled political parties to operate and mobilize citizens. Over time, parties became essential for candidate nominations, electoral campaigns, and legislative cohesion, though their role remains uncodified in the Constitution.

Interest groups, on the other hand, operate within a framework that is even less directly tied to the Constitution. These organizations, which advocate for specific causes or policies, rely heavily on the First Amendment’s guarantees of free speech, assembly, and petition. The right to petition the government for redress of grievances is particularly crucial for interest groups, as it legitimizes their efforts to influence policymakers. While the Constitution does not mention interest groups, the Supreme Court has upheld their activities as protected forms of political expression, most notably in cases like *NAACP v. Alabama* (1958), which safeguarded the privacy of group memberships. Interest groups also benefit from the Constitution’s implicit acknowledgment of a pluralistic society, where diverse interests compete for attention and representation.

The lack of explicit constitutional recognition for both political parties and interest groups has led to debates about their legitimacy and boundaries. Critics argue that parties and interest groups can distort the democratic process, with parties fostering polarization and interest groups amplifying unequal representation. Proponents, however, contend that these entities enhance democratic participation by aggregating interests, mobilizing citizens, and holding government accountable. Despite these debates, both political parties and interest groups have become indispensable components of American politics, operating within the constitutional framework without being formally acknowledged by it.

In conclusion, while neither interest groups nor political parties are mentioned in the Constitution, their roles are deeply embedded in the American political landscape. Political parties function as organizational tools for governance and electoral competition, while interest groups serve as advocates for specific causes and constituencies. Both derive their legitimacy from constitutional principles, particularly the First Amendment, and their evolution reflects the dynamic nature of American democracy. The absence of explicit recognition in the Constitution highlights the adaptability of the document, allowing for the growth of institutions that were not envisioned by the Founding Fathers but have become vital to the functioning of the republic.

Are Political Party Donations Tax Deductible? What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

First Amendment Protections for Interest Groups

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution plays a pivotal role in safeguarding the rights of interest groups, even though these entities are not explicitly mentioned in the document. Interest groups, also known as advocacy groups or special interest groups, rely heavily on the freedoms enshrined in the First Amendment to operate effectively. The amendment guarantees freedoms concerning religion, expression, assembly, and the right to petition the government for redress of grievances. These protections are fundamental for interest groups, as they enable them to voice their concerns, mobilize supporters, and influence public policy without fear of government retribution.

One of the most critical First Amendment protections for interest groups is the freedom of speech. This freedom allows interest groups to express their views, critique government policies, and advocate for changes in legislation. Whether through public speeches, media campaigns, or online platforms, interest groups depend on this freedom to disseminate their messages widely. The Supreme Court has consistently upheld the importance of free speech in democratic processes, recognizing that robust debate and diverse viewpoints are essential for a healthy democracy. For interest groups, this means they can engage in political discourse, even if their opinions are unpopular or controversial.

The right to assembly is another cornerstone of First Amendment protections that benefits interest groups. This right enables organizations to gather members and supporters for meetings, protests, and rallies. Such gatherings are crucial for building solidarity, raising awareness, and exerting pressure on policymakers. Historically, interest groups have used public assemblies to draw attention to their causes, from civil rights movements to environmental campaigns. The government cannot arbitrarily restrict these gatherings, ensuring that interest groups have the space to organize and advocate collectively.

Closely related to the right to assembly is the right to petition the government. This protection allows interest groups to formally request action from government officials, whether through lobbying, filing lawsuits, or submitting public comments on proposed regulations. The ability to petition is a direct mechanism for interest groups to influence policy and hold government accountable. For instance, environmental interest groups often petition federal agencies to enforce stricter pollution standards, while labor unions may petition for better workplace protections. This right ensures that interest groups have a legitimate avenue to engage with the government and seek changes that align with their goals.

While the First Amendment provides robust protections, interest groups must navigate certain limitations. For example, speech that incites imminent lawless action or poses a clear and present danger is not protected. Additionally, the government can impose reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions on assemblies to maintain public order. However, these limitations are narrowly construed to avoid infringing on the core freedoms that interest groups rely on. Courts have consistently emphasized that any restrictions must serve a compelling government interest and be narrowly tailored to achieve that interest.

In conclusion, the First Amendment’s protections of speech, assembly, and petition are indispensable for the functioning of interest groups in the United States. These freedoms enable interest groups to participate actively in the democratic process, advocate for their causes, and hold government accountable. Although interest groups are not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution, the First Amendment ensures they have the tools necessary to operate effectively and contribute to a vibrant, pluralistic society. By safeguarding these rights, the Constitution fosters an environment where diverse voices can be heard and represented in the political arena.

Are Political Party Donations Tax Deductible in New Zealand?

You may want to see also

Political Parties and the Two-Party System

The United States Constitution, crafted in 1787, does not explicitly mention political parties. The Founding Fathers, wary of the factionalism and division they had witnessed in Europe, envisioned a political system where leaders would be elected based on merit and character rather than party affiliation. However, the emergence of political parties was almost immediate, with the Federalist and Anti-Federalist factions forming during the debates over the Constitution's ratification. This early division laid the groundwork for the two-party system that has dominated American politics for most of its history.

The two-party system in the United States is a product of both historical circumstance and structural factors. One key factor is the "winner-take-all" electoral system, where the candidate with the most votes in a district or state wins all the electoral votes or seats. This system discourages the proliferation of multiple parties because it makes it difficult for third parties to gain a foothold. Voters tend to gravitate toward the two major parties—currently the Democratic and Republican Parties—to avoid "wasting" their vote on a candidate unlikely to win. This dynamic reinforces the dominance of the two-party system, as smaller parties struggle to compete in a structure designed to favor the largest coalitions.

Political parties play a crucial role in the American political system by aggregating interests, mobilizing voters, and structuring governance. They serve as intermediaries between the government and the public, helping to translate diverse individual interests into coherent policy platforms. In a two-party system, this often results in broad, centrist platforms designed to appeal to a wide range of voters. While this can lead to compromise and moderation, it can also marginalize more extreme or niche viewpoints, which may struggle to find representation within the major parties. Despite this, the two-party system has proven resilient, adapting to changing societal values and political landscapes over time.

The two-party system also influences the way elections are conducted and how power is distributed. In Congress, for example, the majority party in each chamber holds significant control over the legislative agenda, committee assignments, and leadership positions. This structure incentivizes lawmakers to align with one of the two major parties to maximize their influence. Additionally, presidential elections are heavily shaped by the two-party dynamic, with the Electoral College system further reinforcing the dominance of Democrats and Republicans. Third-party candidates, while occasionally impactful, rarely pose a serious challenge to the two-party duopoly due to structural and financial barriers.

Critics of the two-party system argue that it limits political choice and stifles innovation, as voters are often forced to choose between two dominant parties that may not fully represent their views. Proponents, however, contend that it promotes stability and encourages compromise by forcing parties to build broad coalitions. Regardless of these debates, the two-party system remains a defining feature of American politics, deeply embedded in the nation's political culture and institutions. Its endurance reflects both its adaptability and the challenges faced by any movement seeking to fundamentally alter the existing political structure.

Are Membership Dues Mandatory for Joining a Political Party?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$19.75 $26.99

Constitutional Limitations on Group Influence

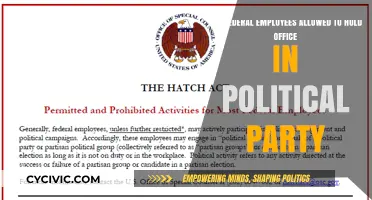

The U.S. Constitution does not explicitly mention interest groups or political parties, yet it establishes a framework that inherently limits their influence. The Constitution’s design, rooted in checks and balances and the separation of powers, ensures that no single group or faction can dominate the political process. Article I, which outlines the powers of Congress, and Article II, which defines the presidency, create a system where decision-making is dispersed among multiple institutions. This diffusion of power prevents interest groups from exerting unchecked control over any one branch of government. Additionally, the Constitution’s emphasis on representative democracy, rather than direct advocacy by groups, underscores that elected officials are accountable to the broader electorate, not just to organized interests.

Another constitutional limitation on group influence is the absence of a guaranteed role for interest groups or political parties in the governance structure. The Constitution focuses on the roles of elected officials, the judiciary, and the states, leaving no formal space for unelected organizations to shape policy directly. Amendments such as the First Amendment protect the rights of groups to assemble, speak, and petition the government, but these freedoms do not translate into formal power within the constitutional framework. This omission ensures that interest groups must operate within the boundaries of public opinion, electoral politics, and the legal system, rather than having a constitutionally enshrined role in governance.

The Constitution’s federalist structure also acts as a constraint on group influence. By dividing power between the federal government and the states, the Constitution limits the ability of interest groups to achieve uniform national policies. Groups must navigate a complex landscape of state and federal jurisdictions, which can dilute their effectiveness. The Tenth Amendment, which reserves powers not granted to the federal government to the states or the people, further ensures that local interests and perspectives remain influential, counterbalancing the efforts of national interest groups.

Judicial review, established in *Marbury v. Madison* (1803), serves as another constitutional check on group influence. The Supreme Court’s power to interpret the Constitution and strike down laws that violate it can limit the impact of interest group-driven legislation. If a law is deemed unconstitutional, it is nullified, regardless of the advocacy efforts behind it. This mechanism ensures that even if interest groups succeed in influencing lawmakers, their achievements must align with constitutional principles, thereby safeguarding against overreach.

Finally, the Constitution’s amendment process imposes a significant barrier to interest group influence. Amending the Constitution requires broad consensus, with proposals needing approval by two-thirds of both houses of Congress and ratification by three-fourths of the states. This stringent process prevents interest groups from making fundamental changes to the nation’s governing document without widespread support. As a result, the Constitution remains a stable and enduring framework that resists manipulation by any single group or faction, ensuring that its limitations on group influence endure over time.

Interest Groups vs. Political Parties: Which Strengthens Democratic Governance?

You may want to see also

Implicit vs. Explicit Mentions in the Constitution

The U.S. Constitution, as the foundational document of American governance, explicitly outlines the structure and powers of the federal government, but its treatment of interest groups and political parties is far more nuanced. Explicit mentions in the Constitution refer to direct references or clear provisions that leave little room for interpretation. For instance, the First Amendment explicitly guarantees freedoms such as speech, assembly, and petition, which are foundational for the operation of interest groups. However, neither "interest groups" nor "political parties" are explicitly named in the Constitution. This absence does not imply irrelevance but rather reflects the framers' focus on broader principles rather than specific entities.

In contrast, implicit mentions arise from the Constitution's structure and the rights it grants, which enable the existence and functioning of interest groups and political parties. The First Amendment's protections for assembly and petition implicitly support the formation of groups advocating for shared interests. Similarly, the democratic processes outlined in Article I and Article II, such as elections and representation, create a framework where political parties naturally emerge as organizers of political competition. These implicit mentions highlight how the Constitution's design fosters an environment conducive to pluralistic political participation.

The distinction between implicit and explicit mentions is crucial for understanding the role of interest groups and political parties in American politics. While the Constitution does not explicitly recognize these entities, it implicitly accommodates them through the rights and structures it establishes. This distinction underscores the adaptability of the Constitution, allowing it to remain relevant in a political landscape vastly different from that of the 18th century. For example, political parties, though unmentioned, have become central to the functioning of the electoral system and governance.

Furthermore, the implicit nature of these mentions has led to ongoing debates about the appropriate role of interest groups and political parties in the constitutional system. Critics argue that the outsized influence of these groups can distort democratic processes, while proponents emphasize their role in facilitating representation and civic engagement. The Constitution's silence on these matters leaves room for interpretation and evolution, reflecting the framers' intent to create a flexible yet enduring framework for governance.

In conclusion, the Constitution's treatment of interest groups and political parties exemplifies the interplay between explicit and implicit mentions. While explicit references provide clear guidelines, implicit mentions allow for the organic development of political institutions. This duality ensures that the Constitution remains a living document, capable of addressing contemporary challenges while staying true to its foundational principles. Understanding this distinction is essential for interpreting the Constitution's relevance to modern political dynamics.

Are Either Political Party Right? Debunking Myths and Finding Common Ground

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, interest groups are not explicitly mentioned in the U.S. Constitution. They operate as part of the broader framework of political participation and free speech protected by the First Amendment.

No, political parties are not mentioned in the U.S. Constitution. The Founding Fathers did not anticipate the rise of political parties, and the document focuses on the structure of government rather than political organizations.

The Constitution does not directly address the role of interest groups or political parties. However, the First Amendment’s protections of free speech and assembly allow for their existence and participation in the political process.

Interest groups and political parties operate within the constitutional framework by exercising rights protected under the First Amendment, such as petitioning the government and organizing for political purposes. They are not formally recognized in the Constitution but are integral to the functioning of American democracy.