Environmental issues are inherently political, as they intersect with power dynamics, policy-making, and resource allocation on local, national, and global scales. The decisions surrounding climate change, pollution, deforestation, and conservation often reflect competing interests between governments, corporations, and communities, with marginalized groups frequently bearing the brunt of environmental degradation. Political ideologies, economic priorities, and international agreements shape how societies address or ignore these challenges, making environmental protection a contentious arena where science, ethics, and governance collide. Thus, understanding environmental issues requires examining the political forces that drive or hinder sustainable solutions.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Policy Influence | Environmental issues are deeply intertwined with political agendas, as policies on climate change, conservation, and pollution are shaped by political ideologies and party platforms. |

| Global Cooperation | Addressing environmental issues often requires international agreements (e.g., Paris Agreement), which are negotiated through political diplomacy and influenced by national interests. |

| Economic Interests | Political decisions on environmental regulations are frequently driven by economic considerations, such as balancing job creation in industries like fossil fuels with sustainability goals. |

| Public Opinion | Political parties often align their environmental stances with public sentiment, as voter priorities on issues like renewable energy or deforestation can sway election outcomes. |

| Lobbying and Advocacy | Corporate and environmental advocacy groups lobby politicians to influence legislation, making environmental issues a battleground for competing political interests. |

| Resource Distribution | Political decisions on resource allocation (e.g., water, land, minerals) often reflect power dynamics and can exacerbate environmental inequalities. |

| Regulatory Frameworks | The strength and enforcement of environmental laws are determined by political leadership, with varying levels of commitment across governments. |

| Climate Justice | Environmental issues are political when they intersect with social justice, as marginalized communities often bear the brunt of pollution and climate impacts, influencing political discourse. |

| Technological Investment | Political decisions on funding for green technologies versus traditional industries shape environmental outcomes and reflect ideological priorities. |

| Crisis Response | Political leadership determines the urgency and effectiveness of responses to environmental crises like wildfires, floods, or oil spills. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Climate policy debates and partisan divides in government decision-making

- Corporate influence on environmental regulations and lobbying efforts

- Global cooperation challenges in addressing cross-border ecological crises

- Environmental justice movements and their political implications

- Role of activism in shaping green political agendas

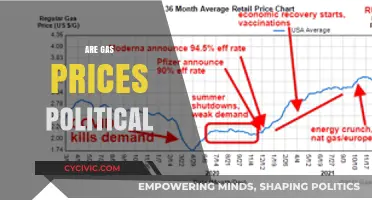

Climate policy debates and partisan divides in government decision-making

Climate policy debates often mirror partisan divides, with government decision-making reflecting ideological priorities rather than scientific consensus. In the United States, for instance, Democratic administrations tend to prioritize emissions reduction targets, renewable energy investments, and international cooperation, as seen in the re-entry into the Paris Agreement under President Biden. Conversely, Republican administrations frequently emphasize energy independence, deregulation, and fossil fuel industries, as evidenced by the rollback of environmental protections during the Trump era. These contrasting approaches highlight how climate policy becomes a battleground for competing visions of economic growth, government intervention, and environmental stewardship.

Consider the legislative process, where partisan divides frequently stall or reshape climate initiatives. The 2009 Waxman-Markey bill, which aimed to establish a cap-and-trade system for carbon emissions, passed the House but failed in the Senate due to Republican opposition and moderate Democratic defections. Similarly, the Green New Deal, championed by progressive Democrats, has been dismissed by Republicans as overly ambitious and economically infeasible. Such examples illustrate how climate policy is not just a technical or scientific issue but a deeply political one, shaped by party platforms, donor interests, and electoral strategies.

To navigate these divides, policymakers must adopt strategies that bridge ideological gaps. One approach is to frame climate action as an economic opportunity rather than a burden. For instance, emphasizing job creation in renewable energy sectors or the cost savings of energy efficiency can appeal to both sides of the aisle. Another tactic is to focus on bipartisan, localized solutions, such as infrastructure resilience projects that address climate impacts without triggering partisan backlash. However, these efforts require careful messaging and coalition-building, as even seemingly neutral policies can become politicized in a polarized environment.

A cautionary note: relying solely on bipartisan compromise can dilute the urgency and scope of climate action. Incrementalism may appease political opponents but risks falling short of the transformative changes scientists say are necessary. For instance, while bipartisan infrastructure bills may include climate-friendly provisions, they often lack the scale and ambition of comprehensive climate legislation. Policymakers must balance pragmatism with boldness, ensuring that short-term political feasibility does not undermine long-term environmental goals.

Ultimately, the partisan nature of climate policy debates underscores the need for a broader cultural shift in how environmental issues are perceived. Until climate action is depoliticized—or at least reframed as a nonpartisan imperative—government decision-making will remain hostage to ideological battles. This requires not only strategic policymaking but also public education, grassroots mobilization, and a rethinking of how political parties define their core values. Without such a shift, climate policy will continue to be a political football, with the planet paying the price for partisan gridlock.

Does Comodo Antivirus Block Political Websites? Exploring the Facts

You may want to see also

Corporate influence on environmental regulations and lobbying efforts

Corporate lobbying has become a powerful force in shaping environmental regulations, often tilting the scales in favor of industry interests over ecological preservation. Consider the 2017 rollback of the Clean Power Plan in the United States, a move heavily influenced by fossil fuel companies. These corporations spent millions on lobbying efforts, arguing that stricter emissions standards would harm economic growth. The result? A significant setback for climate action, as the plan aimed to reduce carbon emissions from power plants by 32% by 2030. This example underscores how corporate influence can directly undermine environmental progress, prioritizing short-term profits over long-term sustainability.

To understand the mechanics of this influence, examine the strategies corporations employ. First, they fund think tanks and research organizations to produce studies that cast doubt on scientific consensus, such as the link between carbon emissions and climate change. Second, they engage in direct lobbying, leveraging their financial resources to gain access to policymakers. For instance, ExxonMobil spent over $15 million on federal lobbying in 2022 alone, advocating against stricter environmental regulations. Third, they use campaign contributions to sway politicians, ensuring their interests are represented in legislative decisions. These tactics create a system where corporate priorities often overshadow environmental concerns.

A comparative analysis reveals that industries with high environmental impact, such as oil, gas, and manufacturing, are among the most active in lobbying efforts. In the European Union, the automotive industry successfully delayed stricter emissions standards for vehicles, arguing for a phased approach that critics deemed too slow. Meanwhile, renewable energy companies, though growing in influence, still lack the financial muscle to counterbalance these efforts. This disparity highlights how corporate lobbying perpetuates a cycle where polluting industries maintain their dominance, hindering the transition to greener technologies.

For those seeking to counteract corporate influence, practical steps can be taken. First, support transparency initiatives that require companies to disclose their lobbying activities and campaign contributions. Second, advocate for stronger ethics rules that limit the revolving door between industry and government. Third, engage in grassroots movements that amplify public demand for environmental protections. For example, the 2018 youth-led climate strikes pressured governments worldwide to take action, demonstrating the power of collective advocacy. By taking these steps, individuals and communities can challenge corporate dominance and push for policies that prioritize the planet.

Ultimately, the intersection of corporate influence and environmental regulations reveals a political landscape where money often speaks louder than science. While corporations wield significant power, history shows that informed, organized resistance can shift the balance. The fight for environmental justice requires vigilance, strategic action, and a commitment to holding both corporations and policymakers accountable. Without addressing this influence, even the most well-intentioned regulations risk being undermined by those who prioritize profit over the planet.

Is Comey Politically Motivated? Unraveling the Former FBI Director's Actions

You may want to see also

Global cooperation challenges in addressing cross-border ecological crises

Cross-border ecological crises, such as transboundary air pollution, ocean acidification, and biodiversity loss, demand global cooperation. Yet, the political fragmentation of nation-states often hinders collective action. For instance, the 1987 Montreal Protocol successfully phased out ozone-depleting substances by aligning 198 parties, but replicating this success for climate change under the Paris Agreement has proven far more complex. The challenge lies in reconciling diverse economic priorities, historical responsibilities, and governance systems, which often prioritize national sovereignty over global ecological imperatives.

Consider the Mekong River, a lifeline for Southeast Asia, where upstream dam construction by China and Laos has disrupted water flow, fisheries, and livelihoods downstream in Cambodia and Vietnam. Despite shared ecological stakes, diplomatic tensions and unequal power dynamics have stymied cooperative solutions. This example underscores how geopolitical rivalries and resource competition can overshadow environmental imperatives, even when the consequences of inaction are dire. Effective global cooperation requires mechanisms that balance equity, accountability, and mutual benefit, yet such frameworks remain elusive in practice.

A persuasive argument for global cooperation lies in the economic and security risks of ecological crises. For example, the 2019 Amazon wildfires, exacerbated by deforestation, not only released 228 megatons of CO₂ but also threatened global agricultural stability by disrupting rainfall patterns. Similarly, the melting of Arctic ice, driven by global warming, has opened new shipping routes, intensifying geopolitical competition among Arctic and non-Arctic states. These crises highlight the interconnectedness of environmental degradation and geopolitical instability, making a compelling case for preemptive, collaborative action rather than reactive, unilateral measures.

To address these challenges, a step-by-step approach is essential. First, establish science-based, cross-border monitoring systems to track ecological changes in real time, as exemplified by the UN’s Global Environment Outlook. Second, create binding international agreements with clear enforcement mechanisms, such as the International Court of Justice’s role in resolving transboundary water disputes. Third, incentivize cooperation through financial mechanisms like the Green Climate Fund, which allocates resources based on vulnerability and mitigation potential. Caution must be taken, however, to avoid tokenism or greenwashing, ensuring that commitments translate into tangible actions.

Ultimately, the political nature of environmental issues complicates global cooperation, but it also presents an opportunity. By framing ecological crises as shared threats to human security and economic prosperity, nations can transcend zero-sum thinking and embrace collaborative solutions. The alternative—a patchwork of unilateral efforts—will only deepen inequalities and accelerate ecological collapse. The challenge is not just technical or scientific but fundamentally political, requiring leadership, trust, and a reimagining of global governance for a sustainable future.

Mastering Political Networking: Strategies to Build Powerful Connections

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental justice movements and their political implications

Environmental justice movements have emerged as a powerful force, challenging the notion that environmental issues are apolitical. These movements highlight how environmental degradation disproportionately affects marginalized communities, often due to systemic inequalities and discriminatory policies. For instance, low-income neighborhoods and communities of color are more likely to be located near toxic waste sites, industrial zones, or areas prone to pollution, a phenomenon known as "environmental racism." This reality underscores the political nature of environmental issues, as it reveals how power structures and policy decisions shape who bears the brunt of ecological harm.

Consider the case of Flint, Michigan, where a cost-cutting decision led to contaminated drinking water, primarily affecting a predominantly Black population. This crisis was not merely a failure of infrastructure but a political issue rooted in systemic neglect and racial disparities. Environmental justice movements respond to such injustices by demanding equitable policies, holding governments and corporations accountable, and advocating for the rights of vulnerable communities. Their activism transforms environmental concerns into political agendas, forcing a reevaluation of how resources are distributed and decisions are made.

To engage with environmental justice movements effectively, start by educating yourself on local and global environmental inequities. Identify organizations like the Environmental Justice Coalition or grassroots groups in your area and support their initiatives through volunteering, donations, or advocacy. Participate in community meetings and public hearings to amplify marginalized voices and push for policy changes. For example, advocating for stricter regulations on industrial emissions in low-income areas can directly address environmental racism. Remember, this work requires persistence and a commitment to intersectionality, as environmental justice is deeply intertwined with racial, economic, and social justice.

A critical takeaway is that environmental justice movements politicize ecological issues by exposing their human dimensions. They challenge the status quo, demanding that environmental policies prioritize equity and inclusivity. For instance, the fight against fossil fuel projects often intersects with Indigenous land rights, as seen in the Standing Rock protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline. These movements demonstrate that environmental activism is not just about preserving nature but about dismantling systems of oppression. By framing environmental issues as political, they mobilize diverse coalitions and push for transformative change, proving that justice for people and the planet are inextricably linked.

Is Liberal Arts Inherently Political? Exploring Ideologies and Education

You may want to see also

Role of activism in shaping green political agendas

Environmental activism has been a driving force in pushing ecological concerns from the margins to the center of political discourse. Movements like Extinction Rebellion and Fridays for Future have harnessed civil disobedience and mass mobilization to demand urgent action on climate change. These campaigns have not only amplified public awareness but also pressured governments to adopt greener policies. For instance, the youth-led climate strikes inspired by Greta Thunberg have led to over 1,000 local and national declarations of climate emergencies worldwide. This demonstrates how activism can create a political climate where inaction becomes untenable.

Consider the strategic steps activists use to shape green agendas. First, they identify specific, measurable policy goals, such as carbon neutrality by 2050 or a ban on single-use plastics. Second, they employ a mix of tactics—petitions, protests, and lawsuits—to sustain pressure on decision-makers. Third, they leverage media and social platforms to frame environmental issues as matters of justice and survival. For example, the Indigenous-led protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline not only halted construction but also highlighted the intersection of environmental and social justice. These methods show how activism translates grassroots energy into tangible political outcomes.

However, the effectiveness of activism in shaping green agendas is not without challenges. Governments often respond with symbolic gestures rather than substantive change, a phenomenon known as "greenwashing." Activists must remain vigilant to ensure policies are implemented and enforced. Additionally, internal divisions within movements—over tactics, priorities, or inclusivity—can dilute their impact. For instance, debates over whether to focus on systemic change or individual behavior can fragment efforts. Overcoming these hurdles requires clear leadership, coalition-building, and a commitment to long-term strategies.

A comparative analysis reveals that activism’s success varies by political context. In democracies with robust civil societies, like Germany or Sweden, environmental movements have directly influenced legislation, such as the phase-out of coal or the adoption of renewable energy targets. In contrast, authoritarian regimes often suppress activism, limiting its ability to shape policy. Yet, even in restrictive environments, activists find creative ways to operate, such as using art or digital campaigns to bypass censorship. This underscores the adaptability of activism as a tool for political change.

In conclusion, activism plays a pivotal role in shaping green political agendas by setting the terms of debate, holding leaders accountable, and mobilizing public support. Its impact is evident in the growing number of countries committing to net-zero emissions and the mainstreaming of environmental justice. However, activists must navigate challenges like greenwashing and internal divisions to sustain their influence. By learning from successes and failures across contexts, environmental movements can continue to drive the transformative policies needed to address the climate crisis.

Reclaiming Hope: Strategies to Overcome Political Burnout and Stay Engaged

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, environmental issues are inherently political because they involve decisions about resource allocation, regulation, and policy-making, which are shaped by power dynamics, interests, and ideologies.

Environmental policies often become politicized because they intersect with economic interests, such as industries reliant on fossil fuels, and differing ideological views on government intervention and individual freedoms.

While individual and community efforts are important, large-scale environmental issues like climate change require political action to implement systemic changes, enforce regulations, and foster international cooperation.

Political parties often differ in their approaches based on their ideologies; for example, some prioritize economic growth and deregulation, while others emphasize sustainability, conservation, and stricter environmental protections.

Yes, international environmental agreements are heavily influenced by politics, as they involve negotiations between nations with varying economic priorities, historical responsibilities, and levels of development.