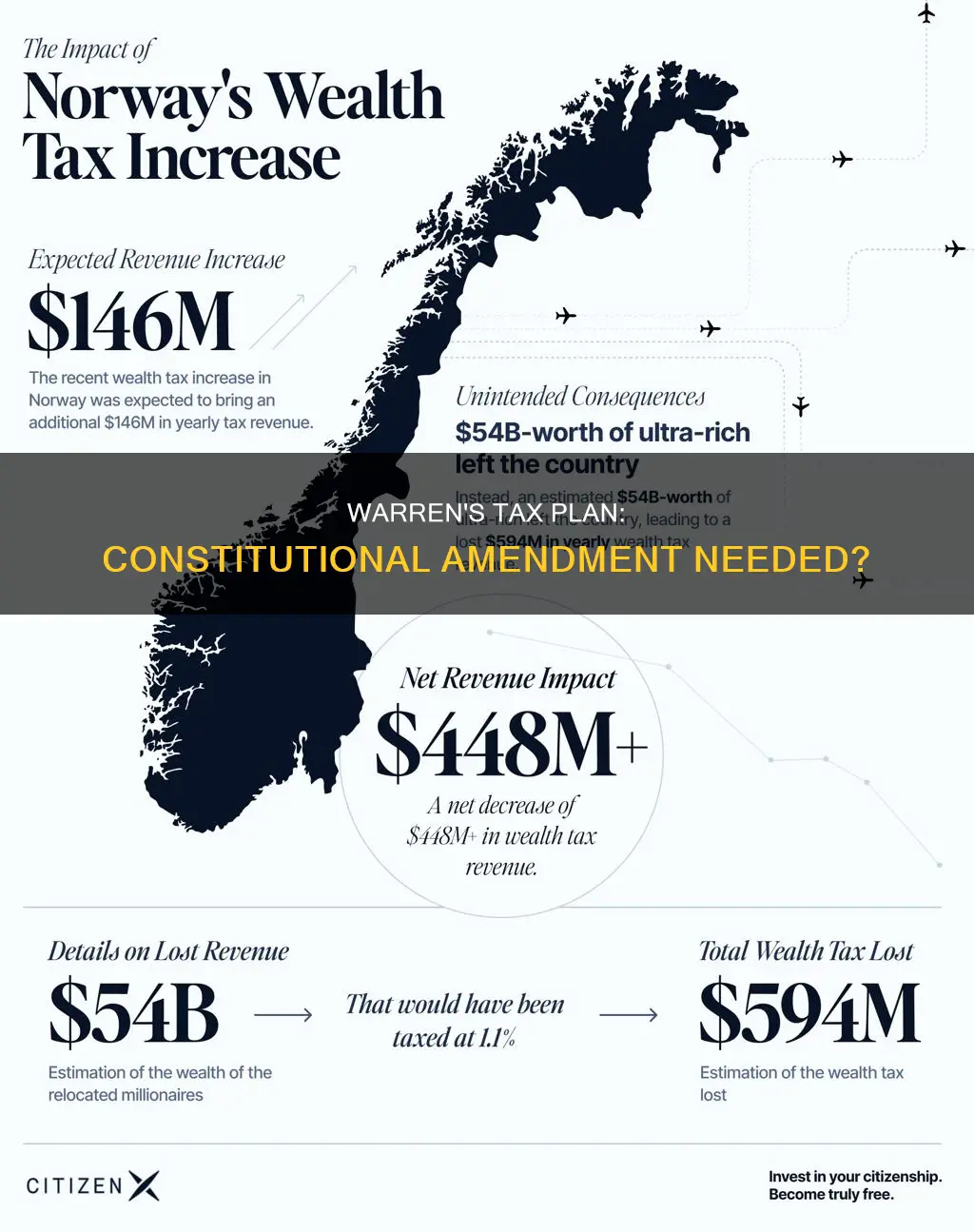

Senator Elizabeth Warren's proposed wealth tax on high-net-worth individuals and households worth over $50 million has sparked debate over its constitutionality. The tax aims to raise trillions of dollars to fund social programs and address wealth inequality. However, legal opinions are divided, with some scholars arguing it would be unconstitutional as a direct tax not apportioned by population, while others contend it falls within the scope of the 16th Amendment. The Supreme Court's interpretation will be pivotal, awakening a dormant area of constitutional law and shaping the future of wealth taxation in the United States.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Proposal | A wealth tax on high-net-worth individuals |

| Tax rate | 2% of wealth over $50 million, with an additional 1% surcharge on wealth over $1 billion |

| Constitutionality | Unclear, potentially unconstitutional as a direct tax that is not apportioned by population |

| Legal opinions | Mixed, with some scholars arguing it is constitutional and others claiming it is not |

| Supreme Court precedent | The Court has not opined on wealth taxes for a long time, but has previously struck down income taxes as direct taxes that were not apportioned |

| Political implications | Could put Warren on a collision course with the Supreme Court, which may determine the success or failure of her administration |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The 16th Amendment

The Sixteenth Amendment (Amendment XVI) to the United States Constitution allows Congress to levy an income tax without apportioning it among the states based on population. It was passed by Congress in 1909 in response to the 1895 Supreme Court case of Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co., which declared certain taxes on incomes to be unconstitutionally unapportioned direct taxes. The 16th Amendment was ratified by the requisite number of states on February 3, 1913, and it effectively overruled the Supreme Court's ruling in Pollock.

The official text of the 16th Amendment is as follows: "The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration." This amendment ensures that Congress can impose taxes on income from any source without having to distribute the total dollar amount of tax collected from each state according to each state's population in relation to the total national population.

Prior to the 16th Amendment, most federal revenue came from tariffs rather than taxes, although Congress had occasionally imposed excise taxes on various goods. The Revenue Act of 1861 introduced the first federal income tax, but it was short-lived and repealed in 1872. During the late 19th century, progressive groups favoured the establishment of a progressive income tax at the federal level, arguing that it was fairer for the wealthy to contribute more.

Understanding Search and Seizure: The Fourth Amendment

You may want to see also

Apportionment

Elizabeth Warren's proposed wealth tax on the top 0.05% of American households, or those worth more than $50 million, has sparked debate over its constitutionality. The main issue is whether the tax constitutes a "direct tax" and, if so, whether it would be "apportioned" in accordance with the Constitution.

The Constitution prohibits federal direct taxes that are not apportioned by population, with the exception of income tax. A direct tax is a levy on a thing, like wealth or income, while an indirect tax is a levy on the transaction of a thing, like the sale of estates, property, or most goods. If a wealth tax is deemed a direct tax, it would need to be apportioned, meaning states with smaller populations would owe more.

The debate centres on Article I, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution, also known as the Apportionment Clause. This clause, written by delegates at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, includes the Three-Fifths Compromise, which counted slaves as three-fifths of a person for determining representation for each state. The Apportionment Clause states that "Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States ... according to their respective Numbers".

The interpretation of the Constitution as a "living document" that can be adapted to modern contexts or as a "sacrosanct and untouchable" text also influences the debate. Some legal scholars argue that the broad taxing power established in the Constitution arose from a specific and narrow debate, and the Apportionment Clause was included to achieve a compromise on questions of representation.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court would likely have the final say on the constitutionality of Warren's wealth tax. However, as of March 2024, legal opinions are mixed, with some scholars arguing it is constitutional, while others believe it violates the Apportionment Clause.

The Constitution: Amendments and their Prohibitions

You may want to see also

Supreme Court rulings

The Sixteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution gives Congress the power to levy and collect taxes on incomes from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the states, and without regard to any census or enumeration. This amendment, ratified in 1913, established the federal income tax system as we know it today. However, the Supreme Court has interpreted this amendment and has placed some limits on Congress's power to tax and spend.

One significant case is United States v. Butler (1936), where the Court struck down a tax on processors of agricultural products, finding that it exceeded Congress's taxing power because its primary purpose was not to raise revenue, but to regulate agricultural production. This decision established the principle that taxes must primarily be for revenue-raising purposes and not for regulating behavior.

Another important case is South Dakota v. Dole (1987), which involved a challenge to a federal law that withheld a portion of federal highway funds from states that did not raise their drinking age to 21. The Court upheld the law, finding that Congress could attach reasonable conditions to the receipt of federal funds and that this particular condition was related to the federal government's power to regulate interstate commerce. This case demonstrates how Congress can use its spending power to influence state behavior.

In terms of a wealth tax specifically, the Supreme Court has not directly addressed whether a wealth tax would be constitutional. However, they have upheld various types of taxes, including income taxes, estate taxes, and excise taxes, as falling within Congress's taxing power. For example, in Knowlton v. Moore (1900), the Court upheld the federal estate tax, finding that it was a valid exercise of the taxing power and did not violate the Constitution.

Additionally, the Court has recognized that the Sixteenth Amendment grants Congress broad powers to tax and spend for the "general welfare." In United States v. Kahriger (1953), the Court stated that "the power of Congress to authorize taxation of all subjects, limited only by express constitutional restrictions, is implicit in the Constitution and was recognized and acted upon by the First Congress." This suggests that a broad range of taxes could be implemented without requiring a constitutional amendment.

However, it's important to note that any specific proposal for a wealth tax would need to be carefully crafted to avoid legal challenges and potential Supreme Court scrutiny. The Court could potentially strike down a wealth tax if it were found to violate other constitutional principles, such as equal protection, due process, or takings clause issues. Therefore, while the Sixteenth Amendment provides a solid foundation for taxation, the specifics of any new tax proposal would need to be carefully scrutinized to ensure compliance with constitutional requirements as interpreted by the Supreme Court.

The 12th Amendment: Written and Ratified in 1700s

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Tax design complexities

The tax design complexities of Elizabeth Warren's proposed wealth tax stem from the question of whether it constitutes a "direct tax" and, if so, whether it would be considered constitutional.

Firstly, it is important to understand what constitutes a "direct tax". Article I of the Constitution, Section 9, bars any "capitation, or other direct, tax" unless it is levied in direct proportion to the population of each state. This is known as "apportionment". The Constitution prohibits federal direct taxes that are not apportioned by population, except for income tax.

The debate surrounding Warren's wealth tax centres on whether it would be considered a direct tax. Some argue that it would, indeed, be a direct tax and thus unconstitutional if not apportioned. This argument is based on the precedent set in the Pollock case of 1895, where the Supreme Court ruled that a federal income tax was unconstitutional as it was considered a direct tax that had not been apportioned.

However, others argue that a wealth tax is not necessarily a direct tax. They draw parallels to the carriage tax, where the Supreme Court manipulated the definition of a direct tax to say that it was not direct and did not need to be apportioned. Additionally, inheritance and estate taxes were upheld in the Knowlton case of 1900, not as direct taxes on wealth but as indirect taxes on the transfer of wealth.

The complexities of defining a "direct tax" and the mixed legal opinions on the matter make it challenging to determine the constitutionality of Warren's wealth tax. The Supreme Court has not opined on this area of tax law for a long time, and while there is precedent, it is not entirely clear-cut.

Ackerman's Constitutional Moments: Legitimate Amendments

You may want to see also

Constitutional interpretation

The constitutional interpretation of Elizabeth Warren's proposed wealth tax centres on the question of whether it constitutes a "direct tax". The US Constitution prohibits federal direct taxes that are not apportioned by population, except for income tax.

A "direct tax" is a mandatory payment collected by governments from individuals or businesses. If a wealth tax is a direct tax, it would have to be apportioned, meaning it would be distributed on a state-by-state basis, depending on each state's population.

The Supreme Court has previously ruled that a federal income tax was unconstitutional, but this was overturned by the 16th Amendment, which allowed income taxes. However, many scholars believe this amendment does not cover a wealth tax.

There are differing opinions on whether a wealth tax would be constitutional. Some argue that it would be considered a direct tax and thus unconstitutional if not apportioned. Others contend that it would not be a direct tax, drawing parallels with income tax, which the Supreme Court has upheld. The precedents go both ways, and it is an area the Court has not addressed for a long time.

The debate also revolves around the interpretation of the Constitution. Some view it as sacrosanct and untouchable, while others see it as more improvised and imperfect. The Supreme Court's decision will be a "test of seriousness", and it remains uncertain how the justices will rule on the matter.

District Plans: Constitutional Amendments Required?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

It is a tax on the top 0.05% of American households, with the aim of taxing the ultra-wealthy.

The US Constitution prohibits federal "direct taxes" that are not apportioned by population, except for income tax. A wealth tax may be considered a direct tax and hence, unconstitutional.

In 1895, the Supreme Court ruled that a federal income tax was unconstitutional unless apportioned. This was later overturned by the 16th Amendment. In 1920, an attempt to tax unrealized capital gains was struck down.