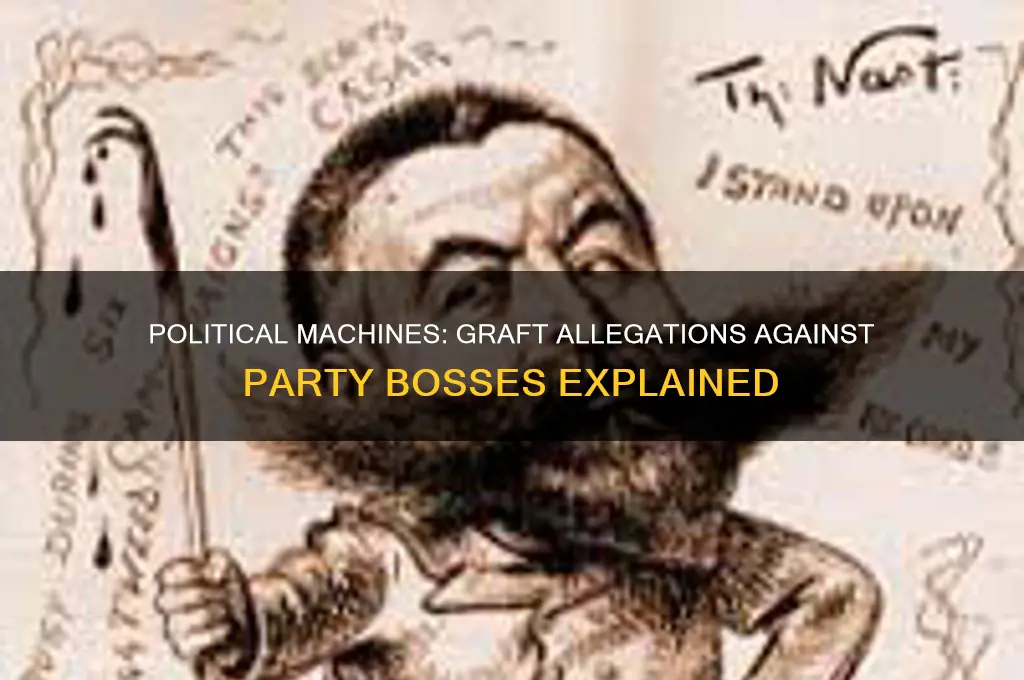

Political machines and party bosses in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were frequently accused of graft due to their pervasive control over urban political systems, which often prioritized patronage and personal gain over public welfare. These organizations, deeply entrenched in cities like New York, Chicago, and Boston, operated by exchanging favors, jobs, and contracts for political loyalty and votes, creating a system ripe for corruption. Graft, or the misuse of public funds and resources for private benefit, became endemic as party bosses awarded government contracts to allies, inflated project costs, and siphoned off taxpayer money. Additionally, the lack of transparency and accountability in these machine-dominated systems allowed for widespread bribery, extortion, and embezzlement. Critics argued that such practices undermined democratic principles, perpetuated inequality, and diverted resources from essential public services, leading to widespread public outrage and eventual reforms aimed at dismantling these corrupt networks.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Corruption and Bribery | Accused of accepting bribes in exchange for political favors, contracts, or appointments. |

| Patronage and Nepotism | Awarded jobs and contracts to loyal party members or family, regardless of qualifications. |

| Vote Buying and Fraud | Engaged in buying votes, ballot stuffing, and other forms of election fraud to secure power. |

| Monopoly on Power | Controlled local governments, often through a single party, stifling opposition and dissent. |

| Exploitation of Immigrants | Exploited immigrant communities by offering protection or jobs in exchange for political support. |

| Lack of Transparency | Operated with little to no transparency, making it difficult to hold them accountable. |

| Control Over Public Services | Used control over public services (e.g., police, sanitation) to reward allies and punish opponents. |

| Graft in Public Contracts | Awarded public contracts to cronies at inflated prices, siphoning taxpayer money. |

| Political Intimidation | Used intimidation tactics to suppress opposition and maintain control over communities. |

| Long-Term Entrenchment | Established systems that ensured their dominance for decades, resisting reform efforts. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Corruption in Public Works Contracts: Bosses awarded contracts to allies, inflating costs for personal gain

- Voter Fraud and Intimidation: Machines manipulated elections through ballot stuffing and coercion

- Patronage and Nepotism: Jobs were given to loyalists, not based on merit

- Bribery and Extortion: Officials demanded bribes for permits, licenses, and favors

- Misuse of Public Funds: Party bosses diverted taxpayer money to fund personal projects

Corruption in Public Works Contracts: Bosses awarded contracts to allies, inflating costs for personal gain

Political machines and party bosses in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were often accused of graft, particularly in the awarding of public works contracts. One of the most pervasive forms of corruption involved bosses directing contracts to their allies, often inflating costs to secure personal financial gain. This practice not only enriched the bosses and their associates but also burdened taxpayers with exorbitant expenses for projects that could have been completed at a fraction of the cost. By controlling the allocation of contracts, these political leaders effectively turned public works into a tool for patronage and self-enrichment, undermining the integrity of government operations.

The process typically began with the manipulation of bidding systems. Party bosses would ensure that only their favored contractors or businesses were aware of upcoming projects or would rig the bidding process to disqualify competitors. These favored contractors, often allies or financial contributors to the political machine, would then submit inflated bids, knowing they would be awarded the contract regardless of the price. The bosses would receive kickbacks, bribes, or other forms of compensation in return for their influence, creating a cycle of corruption that benefited a select few at the expense of the public.

Inflated costs were justified through various means, such as exaggerated project requirements, unnecessary add-ons, or fictitious expenses. For example, a simple road construction project might include inflated material costs, excessive labor charges, or phantom equipment rentals. These tactics not only increased the overall cost of the project but also made it difficult for outsiders to detect the fraud. The lack of transparency and accountability in the contracting process allowed bosses to operate with impunity, as their control over local government often shielded them from scrutiny or legal consequences.

The impact of this corruption extended beyond financial waste. Poorly managed or overpriced public works projects often resulted in substandard infrastructure, posing risks to public safety and long-term durability. Additionally, the diversion of funds meant that other critical public services, such as education, healthcare, and social welfare, were underfunded. This further exacerbated inequality and eroded public trust in government institutions. The public, burdened by higher taxes and reduced services, grew increasingly disillusioned with the political machines that prioritized personal gain over the common good.

Efforts to combat this corruption eventually led to reforms, including stricter bidding laws, increased transparency in contracting processes, and the establishment of independent oversight bodies. However, the legacy of graft in public works contracts remains a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked political power. It underscores the importance of accountability, transparency, and ethical leadership in ensuring that public resources are used for the benefit of all citizens, rather than for the enrichment of a few influential individuals.

Does Khamenei Have a Political Party? Exploring Iran's Leadership Structure

You may want to see also

Voter Fraud and Intimidation: Machines manipulated elections through ballot stuffing and coercion

Political machines and party bosses were frequently accused of graft, and one of the most egregious methods they employed to maintain power was through voter fraud and intimidation. These tactics allowed them to manipulate election outcomes in their favor, often subverting the democratic process. One common practice was ballot stuffing, where machines would artificially inflate vote counts for their preferred candidates. This was achieved by submitting fraudulent ballots, often in the names of deceased individuals, fictitious voters, or people who had not actually cast a vote. By controlling polling places and election officials, party bosses ensured that these fake ballots were counted without scrutiny, effectively stealing elections.

Another insidious strategy was voter coercion, where machines used threats, bribes, or physical intimidation to force voters to support their candidates. Party operatives would station themselves outside polling locations, monitoring who entered and pressuring voters to cast their ballots as instructed. In some cases, voters were given pre-marked ballots or were accompanied into the voting booth to ensure compliance. This tactic was particularly effective in immigrant communities, where language barriers and fear of authority made voters more susceptible to manipulation. The machines exploited these vulnerabilities to secure bloc votes, often under the guise of providing "assistance" or "protection."

Repeat voting was another tool in the machines' arsenal. Party loyalists, known as "repeaters," would vote multiple times in different precincts, taking advantage of the lack of centralized voter records. This practice was facilitated by corrupt election officials who turned a blind eye or actively assisted in the scheme. By casting multiple votes, these operatives could significantly skew election results in favor of the machine's candidates. This form of fraud was difficult to detect and even harder to prosecute, as it relied on the complicity of those tasked with overseeing the electoral process.

Intimidation tactics extended beyond the polling place, with machines employing physical violence and economic threats to suppress opposition votes. Voters who refused to support the machine's candidates might face retaliation, such as losing their jobs, being evicted from their homes, or suffering physical harm. In some cases, entire neighborhoods were terrorized to ensure compliance. This atmosphere of fear effectively silenced dissent and allowed the machines to maintain their grip on power. The use of such tactics not only undermined the integrity of elections but also eroded public trust in the political system.

The machines' ability to manipulate elections through voter fraud and intimidation was a key reason they were accused of graft. By controlling the electoral process, they ensured the continued flow of patronage, contracts, and other benefits to their networks. This corruption perpetuated a cycle of dependency, where politicians and party bosses relied on illicit means to stay in power, while voters were denied their right to free and fair elections. The legacy of these practices serves as a stark reminder of the importance of transparency, accountability, and safeguards in the democratic process.

John Adams' Stance on Political Parties: A Historical Perspective

You may want to see also

Patronage and Nepotism: Jobs were given to loyalists, not based on merit

Political machines and party bosses in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were often accused of graft, and one of the primary reasons was their pervasive use of patronage and nepotism. Instead of awarding jobs based on merit, qualifications, or competence, these systems prioritized loyalty to the party or its leaders. This practice not only undermined the efficiency of public institutions but also fostered corruption and public distrust. Jobs in government offices, from local clerks to high-ranking positions, were frequently handed out as rewards to party loyalists, campaign workers, or family members, regardless of their ability to perform the duties effectively.

The system of patronage allowed party bosses to consolidate power by creating a network of dependents who owed their livelihoods to the machine. These appointees were often expected to kick back a portion of their salaries to the party or work on its behalf during elections, further entrenching the machine's control. For example, in cities like New York or Chicago, positions in the police department, sanitation, or public works were commonly distributed to those who had proven their loyalty to Tammany Hall or other dominant political organizations. This practice not only excluded qualified candidates but also led to inefficiency and mismanagement in public services.

Nepotism, a close cousin of patronage, exacerbated the problem by ensuring that jobs were given to relatives or friends of party bosses rather than to those best suited for the role. This created a culture of favoritism where connections mattered more than competence. For instance, a party boss might appoint his brother-in-law as a judge, his nephew as a city engineer, or his mistress as a clerk, regardless of their qualifications. Such practices not only demoralized honest workers but also led to widespread public cynicism about the integrity of government institutions.

The consequences of patronage and nepotism were far-reaching. Public services suffered as unqualified individuals occupied critical roles, leading to poor decision-making and inefficiency. Moreover, the system discouraged innovation and professionalism, as advancement was based on political loyalty rather than performance. This undermined the principle of equal opportunity and perpetuated inequality, as those without political connections were systematically excluded from government employment.

In summary, the accusations of graft against political machines and party bosses were deeply rooted in their abuse of patronage and nepotism. By prioritizing loyalty over merit, these systems corrupted the hiring process, weakened public institutions, and eroded public trust. Their practices not only benefited a select few at the expense of the broader community but also highlighted the need for civil service reforms to ensure that government jobs were awarded based on competence and qualifications rather than political allegiance.

Can Political Parties Legally Remove Their Own Members from Office?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Bribery and Extortion: Officials demanded bribes for permits, licenses, and favors

Political machines and party bosses were frequently accused of graft, particularly in the form of bribery and extortion, due to their systemic manipulation of power for personal and political gain. One of the most common practices involved officials demanding bribes in exchange for permits, licenses, and favors. This behavior was deeply entrenched in the operations of political machines, which often controlled local and municipal governments. Business owners, contractors, and ordinary citizens seeking official approvals—such as building permits, liquor licenses, or government contracts—were routinely forced to pay bribes to secure these documents. Without such payments, applications were delayed, denied, or buried in bureaucratic red tape, effectively holding individuals and businesses hostage to the demands of corrupt officials.

The extortionate nature of these demands was often thinly veiled. Party bosses and their appointees would exploit their authority over regulatory processes, creating artificial barriers that could only be overcome with financial incentives. For example, a business owner applying for a liquor license might be informed that their application was "incomplete" or "under review" indefinitely, only to be approached by a party operative offering to expedite the process for a fee. This system thrived on fear and dependency, as those who refused to pay risked losing opportunities or facing retaliation, such as increased inspections or revoked approvals. The line between bribery and extortion blurred, as the implicit threat of obstruction made these payments less voluntary and more coercive.

The culture of bribery was sustained by the patronage system, where political machines rewarded loyalists with government jobs and contracts. These appointees, in turn, were expected to funnel kickbacks to party bosses or contribute to campaign funds. This quid pro quo arrangement ensured that graft became institutionalized, with officials viewing bribes as a legitimate source of income. For instance, building inspectors might demand payments to overlook code violations, or police officers could accept bribes to turn a blind eye to illegal activities. The pervasive nature of this corruption eroded public trust in government institutions, as citizens came to see official processes as transactional rather than impartial.

Another aspect of this graft involved the manipulation of public resources for private gain. Party bosses would award lucrative contracts to businesses that paid bribes, regardless of their qualifications or competitiveness. This not only inflated costs for taxpayers but also stifled fair competition, as honest businesses were unable to compete with those willing to engage in corruption. The system was self-perpetuating, as the financial gains from graft funded political campaigns, ensuring the continued dominance of the machine. This cycle of corruption reinforced the power of party bosses, who could then further exploit their control over permits, licenses, and favors to extract more bribes.

In summary, the accusation of graft against political machines and party bosses was rooted in their widespread use of bribery and extortion to control access to permits, licenses, and favors. By weaponizing bureaucratic processes, these officials created an environment where payments were necessary to navigate government systems. This corruption was enabled by patronage networks and the lack of accountability, allowing party bosses to exploit their authority for personal enrichment. The result was a system that undermined fairness, transparency, and public trust, cementing the reputation of political machines as hubs of graft and malfeasance.

Can Government Employees Serve as Poll Greeters for Political Parties?

You may want to see also

Misuse of Public Funds: Party bosses diverted taxpayer money to fund personal projects

The misuse of public funds by party bosses and political machines was a significant aspect of the graft accusations leveled against them. These powerful figures often controlled local and state governments, allowing them to manipulate financial resources for personal gain. One of the most direct forms of graft involved diverting taxpayer money intended for public projects to fund personal ventures or those of their associates. This practice not only depleted public coffers but also deprived communities of essential services and infrastructure improvements. By prioritizing private interests over public welfare, party bosses eroded trust in government institutions and exacerbated socioeconomic inequalities.

Party bosses frequently exploited their influence over government contracts to funnel public funds into their own pockets. They would award contracts to businesses owned by themselves, family members, or political allies, often at inflated prices or for subpar work. For example, a city’s public works department might allocate funds for road repairs, only for the contract to be given to a construction company owned by the party boss’s brother. The project might then be completed at a fraction of the agreed-upon quality, with the remaining funds pocketed by the involved parties. Such schemes were difficult to detect and even harder to prosecute, as the party bosses controlled the very institutions tasked with oversight.

Another common tactic was the creation of "ghost projects" or unnecessary initiatives that existed solely on paper. Party bosses would allocate substantial public funds to these fictitious projects, which were then diverted to their personal accounts or used to finance their political operations. For instance, a city might announce a major park renovation, complete with public ceremonies and press releases, only for the funds to disappear without any visible improvements. This not only misappropriated taxpayer money but also deceived the public into believing their tax dollars were being used responsibly.

The diversion of public funds also extended to the misuse of government employees and resources. Party bosses often required public workers to perform tasks unrelated to their official duties, such as campaigning for the party or maintaining the boss’s personal properties. These employees were paid with taxpayer money, effectively subsidizing the party’s political activities. Additionally, government vehicles, equipment, and supplies were frequently used for personal or party-related purposes, further draining public resources.

The impact of such misuse of funds was far-reaching. Communities suffered from neglected infrastructure, underfunded schools, and inadequate public services, while party bosses and their associates amassed wealth and power. This systemic corruption undermined democratic principles, as elected officials prioritized their personal and political interests over the needs of the constituents they were sworn to serve. The public’s growing awareness of these practices fueled widespread outrage and contributed to the eventual decline of many political machines in the early 20th century.

In conclusion, the diversion of taxpayer money to fund personal projects was a hallmark of the graft associated with political machines and party bosses. Through manipulated contracts, ghost projects, and the exploitation of public resources, these figures systematically misused public funds for private gain. Their actions not only depleted public finances but also eroded public trust and exacerbated social inequalities. Understanding this aspect of graft is crucial to comprehending why political machines and party bosses faced such intense scrutiny and criticism.

Private Funding for Political Parties: Necessary Evil or Democratic Flaw?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political machines and party bosses were accused of graft because they often used their power to award government contracts, jobs, and favors in exchange for bribes, kickbacks, or political support, enriching themselves and their allies at the public's expense.

Practices such as patronage (hiring supporters for government jobs), embezzlement of public funds, and rigging contracts to benefit connected businesses were common, fueling accusations of graft and corruption.

Political machines often justified their actions by claiming they provided essential services to immigrants and the poor, such as jobs, housing, and social support, which mainstream institutions neglected, portraying themselves as necessary for community survival.

Accusations of graft eroded public trust in political machines and party bosses, leading to increased calls for reform, the rise of progressive movements, and the eventual decline of their influence in American politics.