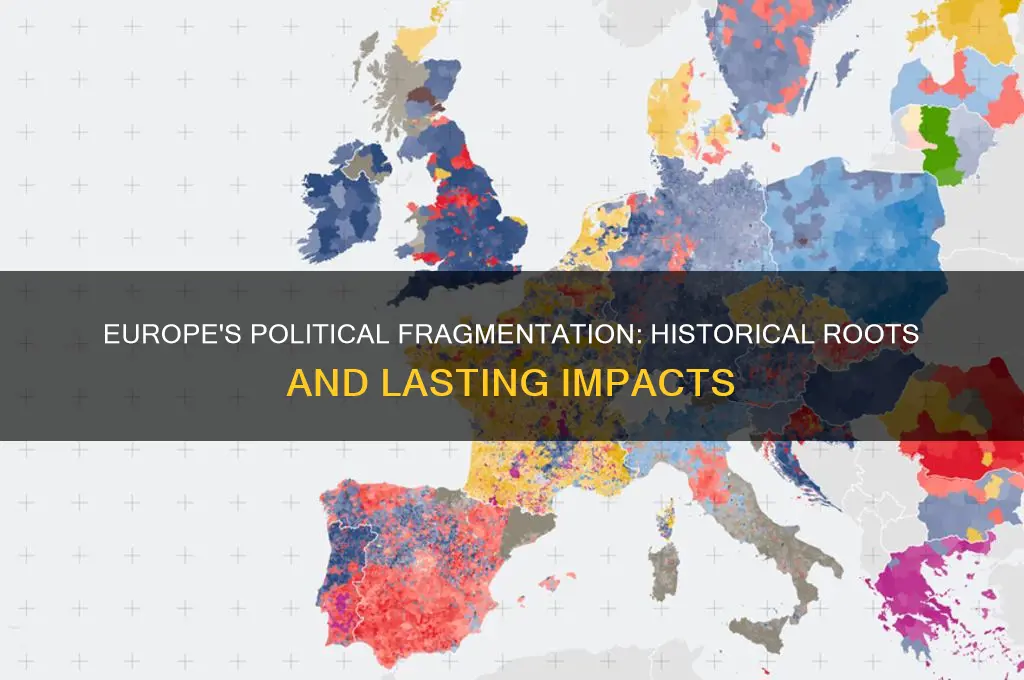

Europe's political fragmentation has deep historical roots, shaped by centuries of diverse cultural, linguistic, and geographic factors. Unlike centralized empires like China, Europe's landscape of forests, mountains, and rivers hindered the formation of a single dominant power, allowing numerous kingdoms, duchies, and city-states to emerge and thrive independently. The fall of the Roman Empire further accelerated this fragmentation, as local leaders filled the power vacuum, establishing their own fiefdoms. Additionally, the rise of feudalism entrenched regional loyalties, while the Catholic Church, though a unifying force, often competed with secular rulers for authority. Wars, dynastic rivalries, and the late emergence of strong nation-states ensured that Europe remained a patchwork of political entities, a legacy that continues to influence its modern identity.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Geographical Diversity | Europe's varied geography (mountains, rivers, forests) hindered centralized governance. |

| Historical Feudalism | Feudal systems created localized power structures, leading to independent principalities. |

| Lack of Central Authority | No single dominant empire or authority emerged to unify Europe politically. |

| Religious Divisions | The Catholic-Orthodox split and later Protestant Reformation fragmented political alliances. |

| Linguistic and Cultural Differences | Diverse languages and cultures made unification difficult. |

| Rise of Nation-States | Emergence of strong national identities (e.g., England, France) prioritized sovereignty. |

| External Threats | Invasions (e.g., Mongols, Ottomans) forced regions to focus on local defense over unity. |

| Economic Fragmentation | Local economies and trade networks reinforced regional autonomy. |

| Treaty of Westphalia (1648) | Established the principle of state sovereignty, cementing political fragmentation. |

| Colonial Competition | Rivalries among European powers over colonies diverted focus from internal unification. |

Explore related products

$53.96 $59.99

$52.24 $54.99

What You'll Learn

- Feudalism's Legacy: Local lords held power, weakening central authority and fostering regional autonomy

- Religious Divisions: Catholic-Protestant split created rival states and alliances, fragmenting unity

- Geographic Barriers: Mountains, rivers, and forests hindered communication and centralized governance

- Dynastic Rivalries: Competing royal families fought for dominance, preventing political consolidation

- Cultural Diversity: Distinct languages, traditions, and identities resisted unification efforts

Feudalism's Legacy: Local lords held power, weakening central authority and fostering regional autonomy

The legacy of feudalism played a pivotal role in Europe's political fragmentation, as it entrenched the power of local lords and eroded central authority. Feudalism, which emerged in the Middle Ages, was a hierarchical system where land was granted in exchange for military service and loyalty. This structure decentralized power, placing significant authority in the hands of local lords who controlled vast territories. These lords, often referred to as vassals, became the de facto rulers of their domains, with the ability to administer justice, collect taxes, and raise armies. Over time, this system weakened the influence of monarchs and central governments, as local lords prioritized their own interests over those of the broader kingdom.

The power of local lords was further solidified by the lack of strong administrative institutions in medieval Europe. Unlike centralized states, where bureaucracies could enforce the ruler's will, feudal Europe relied on personal relationships and local enforcement. This made it difficult for monarchs to assert control over distant regions, as lords often acted with impunity. The fragmentation of authority was exacerbated by the practice of subinfeudation, where lords granted portions of their land to lesser nobles, creating layers of allegiance that further diluted central power. As a result, regional autonomy became the norm, with local lords governing their territories as semi-independent entities.

Feudalism also fostered a culture of regional identity and loyalty, which undermined the concept of a unified nation-state. Peasants and commoners identified more with their local lord and region than with a distant monarch or kingdom. This regionalism was reinforced by linguistic, cultural, and economic differences across Europe, making it challenging to forge a cohesive national identity. Local lords often exploited these divisions to maintain their power, resisting attempts by central authorities to standardize laws, taxes, or governance. This resistance to centralization perpetuated political fragmentation, as regions remained fiercely independent and self-governing.

The military aspect of feudalism further contributed to the weakening of central authority. Local lords were responsible for providing knights and soldiers for their overlords, but this system often led to private armies loyal to individual lords rather than the crown. These armies were frequently used to settle disputes or expand territories, leading to conflicts between lords and even against the monarch. The lack of a standing national army meant that monarchs struggled to enforce their will, as they relied on the cooperation of local lords for military support. This dependency on feudal levies reinforced the power of local lords and hindered the development of strong, centralized states.

In conclusion, the legacy of feudalism was a cornerstone of Europe's political fragmentation. By vesting power in local lords, feudalism weakened central authority and fostered regional autonomy. The absence of strong administrative institutions, the rise of regional identities, and the reliance on local military forces all contributed to a political landscape dominated by decentralized power structures. This fragmentation persisted for centuries, shaping the development of European nations and influencing their governance long after the decline of feudalism itself. Understanding this legacy is essential to grasping why Europe remained politically divided for so much of its history.

Why 'Bitch' is Now Considered Politically Incorrect: Exploring the Shift

You may want to see also

Religious Divisions: Catholic-Protestant split created rival states and alliances, fragmenting unity

The Catholic-Protestant split, which emerged in the 16th century, played a significant role in Europe's political fragmentation. The Protestant Reformation, initiated by Martin Luther in 1517, challenged the authority of the Catholic Church and led to the formation of new Christian denominations, such as Lutheranism, Calvinism, and Anglicanism. This religious schism created deep divisions within European societies, as individuals and rulers chose sides, often based on personal convictions, political expediency, or regional dynamics. As a result, the continent became a patchwork of Catholic and Protestant states, each with its own religious identity and allegiances, which hindered the development of a unified European political landscape.

The religious divide fostered the creation of rival states and alliances, further fragmenting Europe's political unity. Catholic powers, such as the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, and France, often found themselves at odds with Protestant nations like England, Sweden, and various German principalities. These rivalries were not merely theological but also had profound political and economic implications. For instance, the Catholic League, formed in 1594, aimed to curb the spread of Protestantism and maintain Catholic dominance in Europe, while the Protestant Union, established in 1608, sought to protect and promote Protestant interests. These competing blocs contributed to a complex web of alliances and conflicts that made European politics increasingly polarized and fragmented.

The Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), a conflict primarily driven by religious divisions, exemplifies the extent to which the Catholic-Protestant split fragmented Europe. Initially a struggle between Protestant and Catholic states within the Holy Roman Empire, the war eventually escalated into a broader European conflict involving major powers like France, Spain, and Sweden. The war not only devastated large parts of Central Europe but also reinforced the idea that religious differences were incompatible with political unity. The Peace of Westphalia, which ended the war, established the principle of "cuius regio, eius religio," allowing rulers to determine the religion of their states, but it also cemented the fragmentation of Europe into distinct religious and political entities.

Religious divisions influenced the internal politics of states, often leading to fragmentation within individual countries. In regions where both Catholic and Protestant populations coexisted, tensions frequently erupted into civil strife or rebellions. For example, France experienced the Wars of Religion (1562-1598), a series of conflicts between Huguenots (French Protestants) and Catholics that destabilized the country and weakened central authority. Similarly, the English Reformation and the subsequent struggles between Protestants and Catholics shaped the political landscape of England and Ireland, often resulting in periods of instability and fragmentation. These internal divisions made it difficult for European states to present a unified front, either domestically or internationally.

The Catholic-Protestant split also impacted diplomacy and international relations, as religious affiliations often dictated alliances and rivalries. Catholic states tended to align with the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, while Protestant states sought partnerships with fellow reformers. This religious alignment complicated efforts to forge broader political or military coalitions, as religious differences frequently took precedence over shared strategic interests. For instance, the Ottoman Empire, a Muslim power, sometimes found itself as an indirect ally of Protestant states due to their mutual opposition to the Catholic Habsburgs. Such complexities underscored how religious divisions not only fragmented Europe internally but also influenced its external relations, making political unity an elusive goal.

Harris County Ballot: Are Political Party Affiliations Listed for Voters?

You may want to see also

Geographic Barriers: Mountains, rivers, and forests hindered communication and centralized governance

Europe's political fragmentation throughout history can be significantly attributed to the formidable geographic barriers that crisscrossed the continent. Mountains, such as the Alps, Pyrenees, and Carpathians, acted as natural barriers that impeded movement and communication. These towering ranges made travel difficult, especially before the advent of modern transportation technologies. For instance, the Alps, stretching across Central Europe, effectively isolated regions like Italy from the rest of the continent, fostering the development of distinct political entities such as city-states and small duchies. The rugged terrain not only slowed trade and cultural exchange but also made it challenging for any single authority to exert control over vast areas, thus contributing to political fragmentation.

Rivers, while serving as vital trade routes, also played a dual role in fragmenting Europe politically. Major rivers like the Rhine, Danube, and Loire often marked natural boundaries between regions, influencing the formation of distinct political identities. However, their vast networks and seasonal fluctuations made them difficult to cross during certain times of the year, limiting interaction between neighboring territories. Additionally, rivers often became contested zones, with rival powers vying for control over these strategic waterways. This competition further hindered centralized governance, as local rulers or city-states prioritized defending their riverine borders over unifying under a larger political entity.

Forests, particularly the dense woodlands that covered much of medieval Europe, were another significant geographic barrier. Forests like the Ardennes and the Black Forest were not only difficult to traverse but also provided hiding places for bandits and rebels, making them insecure for travel and trade. These vast wooded areas isolated communities, fostering self-reliance and local governance structures. The lack of visibility and control over forested regions made it nearly impossible for centralized authorities to monitor and administer these areas effectively. As a result, forests became natural refuges for independent political entities, further entrenching Europe's fragmented political landscape.

The combined effect of mountains, rivers, and forests created a patchwork of isolated regions, each developing its own distinct culture, economy, and political system. These geographic barriers limited the ability of rulers to project power over long distances, as military campaigns and administrative efforts were often stymied by natural obstacles. For example, the Holy Roman Empire, despite its ambitious name, struggled to maintain centralized control due to the diverse and inaccessible terrains within its borders. The fragmentation was not merely a result of physical barriers but also the logistical and technological limitations of the time, which amplified the isolating effects of Europe's geography.

In conclusion, geographic barriers such as mountains, rivers, and forests were pivotal in shaping Europe's politically fragmented history. They hindered communication, restricted movement, and fostered local autonomy, making it difficult for any single authority to establish centralized governance. These natural obstacles, combined with the technological constraints of pre-modern eras, ensured that Europe remained a mosaic of diverse political entities, each adapting to its unique geographic environment. Understanding this interplay between geography and politics is essential to grasping why Europe developed as a continent of many nations rather than a unified political bloc.

Why Political Thought Shapes Societies and Influences Global Decisions

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$28.92 $30.95

Dynastic Rivalries: Competing royal families fought for dominance, preventing political consolidation

Dynastic rivalries played a significant role in Europe's political fragmentation, as competing royal families vied for power, influence, and territorial control. Throughout the medieval and early modern periods, Europe was characterized by a complex web of monarchies, each seeking to expand its dominion and secure its legacy. These rivalries often led to protracted conflicts, shifting alliances, and a lack of centralized authority, thereby hindering political consolidation. The struggle for dominance among royal dynasties created a highly competitive environment where cooperation was rare, and the balance of power was constantly in flux.

One of the primary drivers of dynastic rivalries was the feudal system, which decentralized political authority and vested power in local lords and monarchs. Royal families sought to extend their influence by marrying into other dynasties, acquiring territories through inheritance, or waging wars of conquest. For instance, the Hundred Years' War (1337–1453) between the English Plantagenets and the French Valois was a direct result of competing claims to the French throne. Such conflicts not only drained resources but also fostered a culture of suspicion and hostility among European powers, making political unity a distant prospect.

The practice of dividing inheritances among multiple heirs further exacerbated dynastic rivalries. Under systems like primogeniture, where the eldest son inherited the entire estate, conflicts were somewhat mitigated. However, in regions where partible inheritance was practiced, such as in the Holy Roman Empire, territories were often split among siblings, leading to weaker, more fragmented states. These smaller entities were then more susceptible to external pressures and internal strife, as rival families sought to exploit divisions for their gain. The fragmentation of the Holy Roman Empire into hundreds of principalities and free cities is a prime example of how dynastic divisions prevented political consolidation.

Religious differences also fueled dynastic rivalries, particularly during the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. Royal families aligned themselves with either Protestantism or Catholicism, using religion as a tool to legitimize their claims and mobilize support. For example, the Habsburgs, staunch defenders of Catholicism, often clashed with Protestant dynasties like the House of Hohenzollern in Prussia. These religious-dynastic conflicts not only deepened political divisions but also internationalized rivalries, as foreign powers intervened to support their co-religionists. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), a conflict driven by both dynastic and religious ambitions, devastated much of Central Europe and underscored the destabilizing impact of such rivalries.

Moreover, the absence of a strong, overarching authority allowed dynastic rivalries to persist and intensify. The Holy Roman Emperor, theoretically the supreme ruler of the Holy Roman Empire, lacked the power to enforce unity or resolve disputes among competing dynasties. Similarly, the Pope's influence was often limited to spiritual matters and could not effectively mediate political conflicts. This power vacuum enabled royal families to act with impunity, pursuing their interests at the expense of broader political stability. As a result, Europe remained a patchwork of rival states, each dominated by a dynasty more concerned with its own survival and expansion than with continental unity.

In conclusion, dynastic rivalries were a major factor in Europe's political fragmentation, as competing royal families fought for dominance and prevented the emergence of a unified political structure. These rivalries, driven by feudalism, inheritance practices, religious differences, and the absence of central authority, created an environment of perpetual conflict and division. The legacy of these struggles is evident in the diverse political landscape of Europe, where national identities and loyalties often took precedence over broader unity. Understanding this dynamic is crucial to comprehending why Europe remained politically fragmented for centuries.

The Power of Polite Speech: Building Respect and Positive Connections

You may want to see also

Cultural Diversity: Distinct languages, traditions, and identities resisted unification efforts

Europe's political fragmentation throughout history can be significantly attributed to its profound cultural diversity, which acted as a formidable barrier to unification efforts. The continent is home to a vast array of distinct languages, each often tied to a specific region or ethnic group. These languages not only served as a means of communication but also as powerful symbols of identity. For instance, the Romance languages (such as French, Spanish, and Italian) evolved from Latin and are deeply intertwined with the national identities of their respective countries. Similarly, Germanic languages (like German and English) and Slavic languages (such as Russian and Polish) fostered strong regional and ethnic loyalties. This linguistic diversity made it difficult for any single power or ideology to dominate, as communication and cultural understanding across these linguistic divides were often limited.

Traditions and customs further reinforced Europe's fragmentation by creating localized identities that resisted broader unification. Each region developed unique practices, from religious rituals to social norms, which became integral to their sense of self. For example, the Catholic traditions in Southern Europe contrasted with the Protestant practices in Northern Europe, often leading to cultural and political divisions. Festivals, folklore, and even culinary traditions became markers of distinctiveness, making it challenging for external forces to impose a unified cultural or political framework. These traditions were not merely social practices but were deeply embedded in the collective consciousness of communities, fostering a strong resistance to homogenization.

National and regional identities played a crucial role in resisting unification efforts, as they were often built on historical narratives of independence and sovereignty. Countries like France, Germany, and Italy, despite eventual unification, had long histories of regional principalities and city-states that cherished their autonomy. These identities were further solidified through art, literature, and historical myths that celebrated local heroes and achievements. For instance, the Renaissance in Italy fostered a strong sense of Italian cultural superiority, while the Enlightenment in France emphasized French rationalism and national pride. Such identities made it difficult for any overarching political entity to gain widespread acceptance without being perceived as a threat to local heritage.

The persistence of these distinct languages, traditions, and identities often led to conflicts and rivalries that hindered political unification. Wars and disputes were frequently fueled by cultural differences, as seen in the numerous conflicts between European powers over centuries. Even when political alliances were formed, such as the Holy Roman Empire or the European Union, cultural diversity ensured that these entities remained loose confederations rather than fully integrated states. The Holy Roman Empire, for example, was famously described as being "neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire" due to its inability to unify the diverse territories under its nominal rule. Similarly, the European Union today grapples with balancing unity and diversity, as member states fiercely protect their cultural and national identities.

In conclusion, Europe's cultural diversity, characterized by distinct languages, traditions, and identities, was a primary factor in its political fragmentation. These elements created strong local loyalties and resisted efforts to impose uniformity, whether through conquest, diplomacy, or ideological movements. While this diversity has been a source of richness and creativity, it has also made political unification a complex and ongoing challenge. Understanding this cultural resistance is essential to comprehending why Europe remained politically fragmented for much of its history and why even modern unification efforts continue to navigate these deep-rooted differences.

Understanding the Tea Party Movement: Origins, Goals, and Political Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Europe was politically fragmented during the Middle Ages due to the collapse of the Roman Empire, which left a power vacuum filled by numerous local rulers, feudal lords, and emerging kingdoms. Weak central authority, geographic barriers, and the rise of regional identities further contributed to this fragmentation.

Feudalism decentralized power by granting local lords control over land and governance in exchange for loyalty to higher authorities. This system created a patchwork of semi-independent territories, weakening the ability of monarchs or emperors to exert unified control over large areas.

Europe's diverse geography, including mountains, rivers, and forests, made communication and travel difficult, hindering the formation of large, centralized states. These natural barriers allowed local rulers to maintain autonomy and resist external control.

Yes, the Catholic Church played a dual role: it provided a unifying cultural and religious framework but also competed with secular rulers for power. The Church's influence often weakened central authority, as it controlled vast territories and had its own political agenda, contributing to fragmentation.