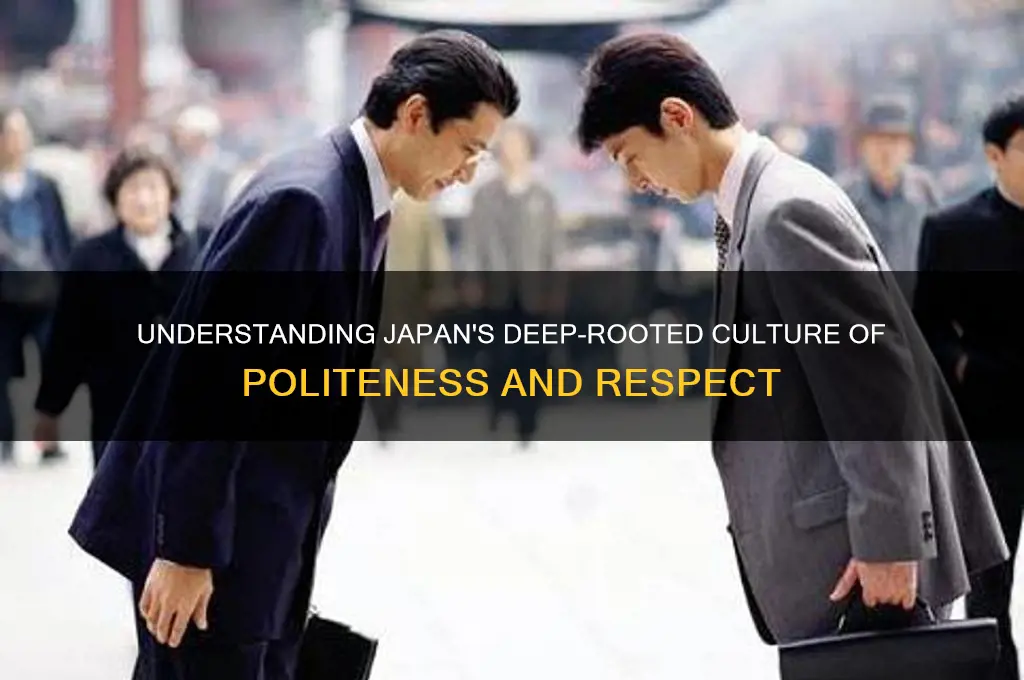

Japanese culture is often celebrated for its emphasis on politeness, rooted in centuries-old traditions and values such as *wa* (harmony) and *omoiyari* (consideration for others). This deep-seated respect for social cohesion is reflected in daily interactions, where formal language, bowing, and adherence to etiquette are commonplace. The influence of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Shintoism has instilled principles of humility, gratitude, and self-discipline, shaping a society that prioritizes collective well-being over individualism. Additionally, Japan’s education system and societal norms reinforce these behaviors from a young age, ensuring that politeness becomes second nature. This cultural framework not only fosters respectful communication but also strengthens social bonds, making politeness a cornerstone of Japanese identity.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Collectivist Culture | Emphasis on group harmony and interdependence, prioritizing community well-being over individual desires. |

| Confucian Influence | Strong respect for hierarchy, elders, and authority figures, shaping polite behavior towards superiors. |

| Shame-Based Society | High sensitivity to social disapproval and loss of face, encouraging conformity and polite conduct. |

| Indirect Communication | Preference for implicit expressions and non-verbal cues to avoid direct confrontation or embarrassment. |

| Honorific Language | Complex system of honorifics (keigo) to show respect based on social status and relationships. |

| Education & Training | Early and consistent emphasis on manners, etiquette, and social norms in schools and families. |

| Service Culture | High standards of customer service and hospitality (omotenashi), ingrained in societal expectations. |

| Religious & Philosophical Roots | Influence of Buddhism, Shintoism, and Taoism promoting humility, mindfulness, and respect for others. |

| Historical Context | Samurai code of conduct (bushido) emphasizing honor, loyalty, and courtesy, which persists in modern values. |

| Population Density | High urbanization and close living conditions necessitate consideration and politeness to maintain harmony. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Cultural Values: Politeness rooted in harmony, respect, and collectivism, prioritizing group well-being over individual desires

- Language Structure: Honorifics and formal speech levels enforce social hierarchy and respectful communication

- Education System: Schools emphasize manners, discipline, and social etiquette from a young age

- Historical Influences: Samurai code (Bushido) and Confucian principles shaped values of honor and courtesy

- Social Pressure: Strong emphasis on avoiding shame and maintaining a positive public image

Cultural Values: Politeness rooted in harmony, respect, and collectivism, prioritizing group well-being over individual desires

Japanese politeness is often observed in the meticulous bowing, the careful choice of words, and the emphasis on non-verbal cues like facial expressions and posture. These behaviors are not mere formalities but deeply ingrained practices rooted in cultural values that prioritize harmony, respect, and collectivism. For instance, the Japanese language itself reflects this ethos, with multiple levels of honorific speech (teineigo, sonkeigo, and kenjougo) used to show respect based on social hierarchy and context. This linguistic precision ensures that interactions remain balanced and considerate, minimizing the risk of conflict or misunderstanding.

To cultivate a similar mindset, consider adopting a practice of active listening and mindful communication. Before speaking, pause to assess the emotional and social dynamics of the situation. For example, in a workplace setting, instead of immediately voicing an opinion, ask open-ended questions to understand others’ perspectives. This approach aligns with the Japanese principle of *wa* (harmony), which values consensus over confrontation. A practical tip: Dedicate 10 seconds to observe body language and tone before responding in any conversation. This small adjustment can foster a more respectful and harmonious exchange.

Contrast this with individualistic cultures, where assertiveness and self-expression are often prized. In Japan, the collective good takes precedence, and politeness serves as a tool to maintain social cohesion. For instance, during rush hour in Tokyo, commuters avoid phone calls in crowded trains to prevent disturbing others—a behavior unthinkable in many other urban settings. This prioritization of group well-being is not just a habit but a reflection of centuries-old Confucian and Buddhist influences, which emphasize interdependence and mutual respect.

A cautionary note: While these values foster unity, they can also lead to suppression of individual desires. For those raised in more individualistic societies, adapting to this collectivist mindset may require conscious effort. Start by identifying areas where personal preferences can be flexibly adjusted for the greater good, such as choosing to dine at a restaurant that accommodates everyone’s dietary restrictions rather than insisting on a personal favorite. Over time, this practice can build empathy and strengthen relationships, aligning with the Japanese ideal of *ki o tsukau* (consideration for others).

Ultimately, Japanese politeness is a manifestation of a cultural framework that values harmony, respect, and collective welfare above individual expression. By integrating these principles into daily interactions—whether through mindful communication, active consideration of others, or flexible decision-making—one can not only understand but also embody the essence of this unique cultural ethos. It’s a practice that transcends borders, offering a blueprint for fostering respect and unity in any community.

How Kids Absorb Political Views: A Developmental Perspective

You may want to see also

Language Structure: Honorifics and formal speech levels enforce social hierarchy and respectful communication

Japanese language structure is a masterclass in embedding respect and hierarchy into daily communication. Unlike English, where tone and context carry much of the weight, Japanese relies on a complex system of honorifics and formal speech levels. These linguistic tools aren’t just niceties—they’re mandatory markers of social standing, relationship, and situation. For instance, the verb "to eat" transforms from *taberu* (casual) to *meshiagaru* (honorific) when speaking to someone of higher status, instantly signaling deference. This grammatical precision ensures that respect isn’t left to chance but is baked into the very fabric of conversation.

Consider the workplace, where this system is most visible. A junior employee addressing their boss uses *desu* and *masu* forms, the polite speech level, while the boss might respond in a more neutral tone. This isn’t rudeness—it’s a reflection of the power dynamic. The language itself enforces the hierarchy, making it nearly impossible to overstep boundaries unintentionally. Even in customer service, clerks use *o-* prefixes (e.g., *o-matase shimashita* for "I kept you waiting") to elevate the customer’s experience, turning a simple interaction into a ritual of respect.

However, this system isn’t without its challenges. Misusing honorifics can lead to embarrassment or offense. For example, using overly formal language with a close friend might imply distance, while being too casual with a superior can be seen as disrespectful. Foreigners often struggle with this nuance, but even native speakers must navigate it daily. The key is context awareness—knowing when to shift from *anata* (you, polite) to *kimi* (you, familiar) or when to drop honorifics entirely in informal settings.

The takeaway? Japanese honorifics and speech levels aren’t just about politeness—they’re a social glue that maintains order and harmony. By encoding respect into grammar, the language minimizes ambiguity and fosters clear, appropriate communication. For learners, mastering these levels is more than a linguistic achievement; it’s a cultural one, offering insight into Japan’s values of hierarchy, humility, and mutual respect. Start with the basics: practice *masu* forms, learn common honorifics like *go- and *o-, and observe how natives adapt their speech. Over time, you’ll not only speak Japanese—you’ll understand the mindset behind it.

Is Aegis Defenders Political? Exploring Themes and Implications in the Game

You may want to see also

Education System: Schools emphasize manners, discipline, and social etiquette from a young age

Japanese schools begin instilling manners and discipline as early as kindergarten, where children learn to bow, say "thank you," and clean up after themselves. This structured approach to social etiquette is not just about individual behavior but about fostering a sense of community and mutual respect. For instance, students often participate in *sōji* (cleaning time), where they sweep classrooms and wipe down desks together, a practice that teaches responsibility and teamwork from age 6. This daily ritual, repeated throughout their school years, embeds habits of tidiness and cooperation that extend beyond the classroom.

The curriculum itself integrates lessons on politeness, with dedicated subjects like *dōtoku* (moral education) introduced in elementary schools. Here, students learn the importance of greetings, apologizing sincerely, and considering others’ feelings. Teachers often use role-playing scenarios to simulate real-life interactions, such as how to politely refuse an invitation or ask for help. By age 10, children are expected to master basic social norms, like removing shoes before entering a home or using respectful language (*keigo*) with elders. These skills are not just taught but reinforced through constant practice and observation.

Discipline in Japanese schools is not punitive but preventive, focusing on self-regulation and self-awareness. Students are encouraged to reflect on their actions through *hansei* (self-reflection), a practice that promotes accountability and empathy. For example, if a student forgets to greet a teacher, they might write a short reflection on why it’s important and how they’ll improve. This method shifts the focus from external punishment to internal growth, aligning with the cultural value of *wa* (harmony). By middle school, most students internalize these principles, demonstrating restraint and consideration even without supervision.

Comparatively, this system contrasts sharply with Western education models, where social etiquette is often left to parents or learned informally. In Japan, schools act as a second home, shaping not just academic skills but also character. The result is a society where politeness is second nature, not a conscious effort. For parents or educators looking to replicate this, start small: introduce daily routines like family clean-up time or practice role-playing polite conversations. Consistency is key—just as Japanese schools do, make these practices non-negotiable parts of daily life.

Is Japan Politically Liberal? Exploring Its Governance and Ideological Stance

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Historical Influences: Samurai code (Bushido) and Confucian principles shaped values of honor and courtesy

The samurai code, known as Bushido, and Confucian principles have deeply ingrained values of honor and courtesy into Japanese culture. These historical influences are not mere relics of the past but living traditions that continue to shape social interactions today. Bushido, the way of the warrior, emphasized loyalty, self-discipline, and respect, while Confucianism taught the importance of harmony, filial piety, and proper conduct. Together, they created a foundation where politeness is not just a social norm but a moral obligation.

Consider the ritual of bowing, a gesture so ubiquitous in Japan that it’s performed millions of times daily. This act of respect traces its roots to both Bushido and Confucianism. The samurai bowed to show deference to superiors, while Confucian teachings elevated it as a symbol of mutual respect and social order. Today, the depth and duration of a bow still communicate nuances of respect, gratitude, or apology. For instance, a slight nod might suffice among colleagues, but a deeper, longer bow is reserved for elders or those of higher status. This practice is a tangible example of how historical values manifest in modern behavior.

To understand the enduring impact of these influences, examine the concept of *giri* (duty) and *ninjo* (human feeling). Bushido stressed the importance of fulfilling one’s obligations, often at great personal cost, while Confucianism emphasized duty to family and community. These principles fostered a society where politeness is not just about personal manners but about maintaining social harmony. For example, Japanese people often prioritize collective well-being over individual desires, such as wearing masks during illnesses to avoid inconveniencing others—a practice rooted in these historical values.

A practical takeaway for anyone interacting with Japanese culture is to recognize the depth behind seemingly simple acts of politeness. For instance, when receiving a gift, take time to admire the wrapping before opening it, as this shows appreciation for the giver’s effort—a behavior influenced by Confucian emphasis on thoughtfulness. Similarly, when apologizing, use phrases like *sumimasen* (excuse me) or *gomen nasai* (I’m sorry) with sincerity, as Bushido values accountability and humility. These small but intentional actions demonstrate respect for the cultural underpinnings of Japanese politeness.

Incorporating these principles into daily life, whether in Japan or elsewhere, requires mindfulness and adaptability. Start by observing and mimicking local customs, such as removing shoes before entering a home or using polite language (*keigo*) in formal settings. Over time, these practices become second nature, fostering deeper connections and mutual respect. By understanding the historical roots of Japanese politeness, one not only navigates the culture more effectively but also appreciates the richness of its traditions.

Polling Power: Shaping Political Strategies and Public Opinion Dynamics

You may want to see also

Social Pressure: Strong emphasis on avoiding shame and maintaining a positive public image

In Japan, the fear of bringing shame upon oneself or one's family is a powerful motivator for polite behavior. This cultural phenomenon, deeply rooted in Confucian principles and reinforced through generations, creates an environment where individuals are acutely aware of their public image. A single misstep, whether it’s speaking too loudly on a train or failing to bow properly, can lead to social ostracism or loss of face. This pressure to conform is not merely about following rules but about preserving harmony within the community. For instance, the act of apologizing, even when not at fault, is common because it prioritizes group cohesion over individual pride.

Consider the Japanese concept of *tatemae*, or public facade, which dictates that one’s outward behavior should always reflect societal expectations, regardless of personal feelings. This practice is particularly evident in workplaces, where employees often prioritize the company’s reputation over their own grievances. A study by the Japan Productivity Center found that 70% of workers reported suppressing their true opinions to avoid conflict or embarrassment. Such self-censorship is not seen as weakness but as a virtue, demonstrating respect for hierarchy and collective well-being.

To navigate this high-pressure environment, individuals adopt specific strategies. One practical tip is mastering the art of *kuuki wo yomu* (reading the air), which involves gauging social cues and adjusting behavior accordingly. For example, during a group outing, someone might notice a shift in mood and immediately offer to pay for the next round of drinks to restore harmony. Another strategy is maintaining a low profile; standing out, even positively, can invite scrutiny. This is why Japanese students often downplay achievements, using phrases like *jibun wa futsuu desu* (“I’m just average”) to deflect praise.

Comparatively, this emphasis on avoiding shame contrasts sharply with cultures that celebrate individualism. In the U.S., for instance, public failures are often reframed as learning opportunities, whereas in Japan, they can be career-ending. However, this system has its drawbacks. The constant need to uphold a flawless image can lead to stress and mental health issues, as evidenced by Japan’s high rates of *karoshi* (death by overwork). Yet, for many, the trade-off is worth it, as maintaining honor and respect remains a cornerstone of Japanese identity.

In conclusion, the social pressure to avoid shame in Japan is both a driving force behind its renowned politeness and a double-edged sword. While it fosters a society where respect and harmony are paramount, it also imposes significant emotional burdens. Understanding this dynamic offers valuable insights into Japanese culture and highlights the delicate balance between collective expectations and individual well-being. For those interacting with Japanese individuals or visiting Japan, recognizing this pressure can lead to more empathetic and culturally sensitive engagement.

Has OPD Located Seneca Polite? Latest Updates and Developments

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Japanese culture places a strong emphasis on harmony, respect, and social order, rooted in Confucian principles and the concept of *wa* (和), meaning peace and unity. Politeness is seen as essential to maintaining these values in daily interactions.

No, Japanese politeness varies depending on context, relationship, and hierarchy. For example, language and behavior differ between speaking to a superior, a peer, or a stranger, with formal and informal levels of speech (*keigo*) used accordingly.

Yes, Japanese education emphasizes discipline, respect for others, and collective responsibility from a young age. Children are taught to prioritize group harmony and show consideration for others, which reinforces polite behavior.

Absolutely. Politeness is not just a personal trait but a societal expectation. Being impolite can be seen as disruptive or disrespectful, and individuals are often mindful of how their actions reflect on their family, workplace, or community.