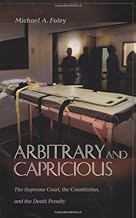

The death penalty is a contentious issue, with debates over its legality and morality. While it does not violate the Eighth Amendment per se, it must be proportional to the crime committed. The Supreme Court has played a pivotal role in shaping the application of the death penalty, with landmark cases such as Furman v. Georgia in 1972, where the death penalty was deemed unconstitutional due to arbitrary sentencing. The Court's decision set a precedent, holding that punishment must not be cruel and unusual, and it cannot be arbitrary, offensive to society's sense of justice, or less effective than a less severe penalty. The Court's role in fine-tuning the death penalty has continued, with rulings on jury discretion, intellectual disability, and proportionality, ensuring that sentencing procedures are individualized and do not violate the Eighth Amendment's ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Death penalty is cruel and unusual punishment | Violates the Eighth Amendment |

| Arbitrariness of the death penalty | Violates the Eighth Amendment |

| Death penalty is disproportionate to the crime | Violates the Eighth Amendment |

| Death penalty is not a more effective penalty than a less severe one | Violates the Eighth Amendment |

| Death penalty offends society's sense of justice | Violates the Eighth Amendment |

| Death penalty is applied in discriminatory ways | Violates the Eighth Amendment |

| Death penalty is applied arbitrarily and capriciously | Violates the Eighth Amendment |

| Death penalty is applied without an individualized sentencing process | Violates the Eighth Amendment |

| Death penalty is applied without considering mitigating circumstances | Violates the Eighth Amendment |

| Death penalty is applied without considering the specific facts of the case | Violates the Eighth Amendment |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The death penalty is a cruel and unusual punishment

The death penalty has been a contentious issue in the United States for decades, with many arguing that it is a cruel and unusual punishment and thus unconstitutional. The Eighth Amendment of the US Constitution states: "Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted." While the Amendment does not categorically prohibit the death penalty, it does set standards that a punishment must adhere to.

The debate over whether the death penalty constitutes cruel and unusual punishment dates back to the Founding Fathers. In 1789, during the debate over the Bill of Rights, there was disagreement over the extent of the death penalty. The Supreme Court's 1972 decision in Furman v. Georgia was a watershed moment in this debate. The Court found that existing sentencing procedures in capital cases violated the Eighth Amendment due to evidence of discriminatory application of the death penalty. The ruling effectively constitutionalized capital sentencing law and involved federal courts in extensive review of capital sentences. However, the death penalty itself was not deemed unconstitutional. This decision was clarified in 1976, when the Court put the death penalty back on the books under different circumstances.

In the 1960s, challenges to the fundamental legality of the death penalty emerged. Abolitionists argued that the death penalty constituted cruel and unusual punishment and was therefore unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment. They pointed to the Supreme Court's decision in Trop v. Dulles (1958), which suggested that the Eighth Amendment contained an evolving standard of decency that marked the progress of a maturing society. According to this interpretation, the United States had progressed to a point where its standard of decency should no longer tolerate the death penalty.

The Supreme Court has also addressed the problems associated with the role of jurors and their discretion in capital cases. In Crampton v. Ohio and McGautha v. California (1971), the defendants argued that it was a violation of their Fourteenth Amendment right to due process for jurors to have unrestricted discretion in deciding whether the defendants should live or die. They claimed that such unrestricted discretion resulted in arbitrary and capricious sentencing. The Supreme Court agreed, setting the standard that a punishment would be cruel and unusual if it was too severe for the crime, if it was arbitrary, if it offended society's sense of justice, or if it was not more effective than a less severe penalty.

In recent years, the Supreme Court has continued to refine its position on the death penalty. In 2002, the Court held that executions of mentally disabled criminals constitute cruel and unusual punishments prohibited by the Eighth Amendment. Additionally, in 2005, the Court ruled that the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments forbid the imposition of the death penalty on offenders who were under the age of 18 when their crimes were committed. These rulings reflect a growing trend toward abolition of the death penalty, both within the United States and internationally.

Safeguarding Democracy: The Constitution's Two-Pronged Approach

You may want to see also

It is applied in discriminatory ways

The Eighth Amendment of the US Constitution forbids cruel and unusual punishment, but this does not categorically prohibit the death penalty. However, the death penalty has been deemed unconstitutional in certain cases where it was applied in discriminatory ways.

In 1972, the Supreme Court ruled in Furman v. Georgia that the death penalty application in three cases was unconstitutional. The ruling effectively constitutionalized capital sentencing law and involved federal courts in an extensive review of capital sentences. The Furman decision was based on the argument that capital cases resulted in arbitrary and capricious sentencing. The Supreme Court set the standard that a punishment would be cruel and unusual if it was too severe for the crime, if it was arbitrary, if it offended society's sense of justice, or if it was not more effective than a less severe penalty. The ruling led to a four-year moratorium on all executions until 1976, when the Court confirmed that capital punishment was legal but under limited circumstances.

The Furman decision was a watershed moment in capital punishment jurisprudence, as it addressed the issue of discrimination in sentencing. Defendants from minority populations or impoverished backgrounds were disproportionately likely to receive capital punishment. The Supreme Court's ruling in Furman v. Georgia and the subsequent Gregg cases in 1976 established that sentencing discretion must be limited to prevent courts from arbitrarily imposing the death penalty. This ruling set a precedent for reviewing and amending policies and procedures that create or perpetuate racial discrimination, as required by the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), ratified by the United States in 1994.

The Supreme Court has also provided further clarification on the principle of individualized sentencing. In Ring v. Arizona (2002), the Court held that it is unconstitutional for a sentencing judge, without a jury, to find an aggravating circumstance necessary for the imposition of the death penalty. The Court has established that courts should follow guidelines that narrow and define the category of death-eligible defendants, while preserving jury discretion to weigh the mitigating circumstances of individual defendants.

In summary, the death penalty has been deemed unconstitutional in certain cases due to its discriminatory application. The Supreme Court's rulings have set standards for proportionality and individualized sentencing, addressing issues of racial discrimination and arbitrary sentencing. These rulings have had a significant impact on capital punishment jurisprudence, leading to a more nuanced approach to the death penalty in the United States.

New Jersey's 1776 Constitution: A Revolutionary Framework

You may want to see also

It is imposed disproportionately on minorities and the poor

The issue of arbitrariness in the application of the death penalty has been a matter of significant legal debate, with the Supreme Court addressing it in several landmark cases. In Furman v. Georgia (1972), the Court held that the death penalty application in three cases was unconstitutional, finding it to be "harsh, freakish, and arbitrary." This decision set a standard that punishment would be considered cruel and unusual if it was too severe for the crime, arbitrary, offended society's sense of justice, or was not more effective than a less severe penalty.

The Furman decision highlighted the issue of discriminatory application of the death penalty, particularly against defendants from minority populations and impoverished backgrounds. This prompted a review of state sentencing rules and a push for more individualized sentencing processes. The Court's ruling in Gregg v. Georgia (1976) reaffirmed the constitutionality of capital punishment but under limited circumstances, rejecting automatic sentencing to death and addressing the issue of discrimination.

Despite these efforts, concerns remain about the disproportionate impact of the death penalty on minorities and the poor. In 1994, the United States ratified the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), a treaty aimed at preventing racial discrimination in all its forms. As a signatory, the United States has an obligation to review and amend policies that perpetuate racial discrimination, including in capital punishment.

The debate over the death penalty's constitutionality continues, with opponents arguing that it is a cruel and unusual punishment that violates the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments. The Supreme Court's rulings have refined the requirements for imposing the death penalty, emphasizing the need for aggravating factors and individualized sentencing processes. However, the fact that minorities and the poor remain disproportionately affected by capital punishment underscores the ongoing need for reform and a continued evaluation of sentencing procedures.

California vs US: Constitution Length Comparison

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$39.95 $34

It is applied arbitrarily

The issue of arbitrariness in the application of the death penalty has been a matter of significant legal debate and has been addressed in several landmark Supreme Court cases. The concept of arbitrariness in capital sentencing refers to the idea that the death penalty is imposed in an inconsistent, capricious, and unpredictable manner, lacking clear and objective standards. This is considered a violation of the Eighth Amendment's prohibition of "cruel and unusual punishments."

One of the earliest cases to address arbitrariness was Furman v. Georgia in 1972. In this case, the Supreme Court found that Georgia's death penalty statute, which gave the jury complete sentencing discretion, could result in arbitrary sentencing. The Court held that the application of the death penalty in these cases was unconstitutional, characterizing it as "harsh, freakish, and arbitrary." This decision set a precedent, establishing that a punishment could be deemed cruel and unusual if it was arbitrary, offended society's sense of justice, or was not more effective than a less severe penalty.

The issue of jury discretion in capital cases was further examined in McGautha v. California and Crampton v. Ohio in 1971. The defendants in these cases argued that unrestricted jury discretion in deciding between life and death resulted in arbitrary and capricious sentencing. The Supreme Court's ruling in these cases contributed to the evolving standards for capital punishment and the need for consistent and objective criteria.

In the 1968 case of U.S. v. Jackson, the Supreme Court addressed the role of the prosecutor and jury in capital cases. The Court found it unconstitutional to impose the death penalty solely upon the recommendation of a jury, as it encouraged defendants to waive their right to a jury trial to avoid a potential death sentence. This decision highlighted the importance of procedural fairness and the need to mitigate arbitrariness in sentencing.

In subsequent years, the Supreme Court continued to refine the criteria for imposing the death penalty, emphasizing the requirement for individualized sentencing processes. In Ring v. Arizona (2002) and Brown v. Sanders (2006), the Court clarified that aggravating circumstances necessary for the death penalty must be found by a jury and based on the specific facts of the case and the defendant. These rulings ensured that sentencing decisions were based on a thorough consideration of mitigating and aggravating factors, reducing the potential for arbitrariness.

While the death penalty itself has not been deemed categorically unconstitutional, the Supreme Court's rulings have established crucial safeguards to prevent its arbitrary application. These decisions have shaped sentencing guidelines, narrowed the category of death-eligible defendants, and ensured that sentencing procedures are proportional to the crime and individualized. The ongoing legal discourse reflects a commitment to upholding constitutional principles and safeguarding against the arbitrary imposition of capital punishment.

Who Holds the Purse Strings?

You may want to see also

It is not proportional to the crime

The death penalty is a contentious issue, and its constitutionality has been questioned and challenged on several occasions. While it is not explicitly prohibited per se, it is essential to understand the arguments surrounding its proportionality to the crime committed.

In the United States, the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution forbids "cruel and unusual punishments." The interpretation of this phrase has been a subject of debate, with abolitionists arguing that the death penalty falls under this category. The Supreme Court, in Trop v. Dulles (1958), decided that the Eighth Amendment contained an "evolving standard of decency that marked the progress of a maturing society." This set a precedent for future challenges to the death penalty.

In Furman v. Georgia (1972), the Supreme Court ruled that the death penalty application in three cases was unconstitutional due to the arbitrary nature of sentencing, which violated the Eighth Amendment. This decision did not abolish the death penalty but set a new standard, requiring that punishments must be proportional to the crimes. The ruling emphasized that a punishment could be considered "cruel and unusual" if it was too harsh for the crime, arbitrary, offensive to society's sense of justice, or less effective than a less severe penalty. This case highlighted the importance of individualized sentencing, where the specific circumstances of the criminal and the facts of the case must be considered.

In Coker v. Georgia (1977), the Supreme Court further elaborated on proportionality, considering the gravity of the offense, the stringency of the penalty, and how other jurisdictions punish the same crime. The Court held that a penalty must be proportional to the crime; otherwise, it violates the Eighth Amendment. This was reaffirmed in Kennedy v. Louisiana (2008), where the Court decided that the death penalty was disproportionate for child rape cases, as only six states permitted execution for such crimes.

The Supreme Court has also addressed the issue of discrimination in capital punishment. In Gregg v. Georgia, the Court determined that revised sentencing procedures addressed discrimination concerns and that the death penalty does not inherently violate the Constitution. However, it is important to note that states have substantial discretion in determining execution methods, which must not cause unnecessary suffering.

In conclusion, while the death penalty itself has not been deemed unconstitutional, its application must adhere to strict standards of proportionality and individualized sentencing. The Eighth Amendment's prohibition of cruel and unusual punishments sets a benchmark for sentencing, ensuring that punishments fit the crimes and reflect evolving societal standards of decency.

The Constitution: Our Rights and Freedoms Framework

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The 8th Amendment of the US Constitution forbids cruel and unusual punishment.

The 8th Amendment does not prohibit the death penalty outright, but any sentence given must be proportional to the crime.

The Supreme Court considers the gravity of the offense and the stringency of the penalty, how the jurisdiction punishes other criminals, and how other jurisdictions punish the same crime.

The death penalty was first challenged in the early 1960s as a form of cruel and unusual punishment. In 1972, the Supreme Court ruled that the death penalty was unconstitutional in Furman v. Georgia, but this was reversed in 1976.

There are concerns about arbitrariness and discrimination in sentencing, as well as a worldwide trend towards abolition. The Supreme Court has also held that the death penalty cannot be imposed on minors or mentally disabled individuals.