Third parties have periodically emerged in American politics as a response to perceived failures or limitations of the dominant two-party system, often reflecting societal shifts, unaddressed issues, or ideological gaps left by the Democratic and Republican parties. Their rise is typically fueled by voter dissatisfaction with the status quo, polarization, or the inability of major parties to tackle pressing concerns such as economic inequality, social justice, or environmental crises. Historically, third parties like the Populists, Progressives, and more recently, the Libertarian and Green Parties, have served as platforms for innovative ideas, pushing mainstream parties to adopt new policies or highlighting neglected issues. While rarely winning elections, these parties play a crucial role in shaping political discourse, mobilizing grassroots movements, and offering alternatives to disillusioned voters, thereby challenging the duopoly and fostering a more dynamic political landscape.

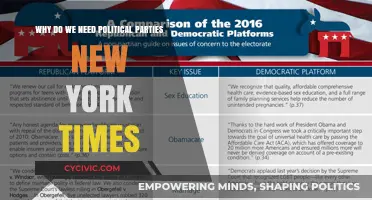

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Dissatisfaction with Major Parties | Voters feel alienated by the policies or candidates of Democrats and Republicans. |

| Polarization | Increasing ideological divide between the two major parties pushes voters toward alternatives. |

| Specific Issues | Third parties often emerge to address niche or ignored issues (e.g., climate change, election reform). |

| Regional Grievances | Local or regional issues not addressed by national parties (e.g., states' rights, rural concerns). |

| Charismatic Leadership | Strong personalities or leaders can galvanize support for third-party movements. |

| Economic Discontent | Economic instability or inequality fuels support for parties offering radical solutions. |

| Electoral System Flaws | Criticism of the two-party system and calls for ranked-choice voting or proportional representation. |

| Social Movements | Third parties often arise from social movements (e.g., civil rights, environmentalism). |

| Media and Technology | Increased visibility through social media and digital platforms helps third parties gain traction. |

| Short-Term Protests | Voters use third parties as a protest vote against the establishment in specific elections. |

| Demographic Shifts | Changing demographics (e.g., younger voters, diverse populations) seek representation beyond major parties. |

| Perceived Corruption | Public distrust in the political establishment drives support for outsider parties. |

| Historical Precedents | Past successes of third parties (e.g., Progressive Party, Reform Party) inspire new movements. |

| Funding and Resources | Increased access to funding and organizational resources enables third parties to compete. |

| Global Influences | International trends or movements (e.g., populism, green politics) inspire domestic third parties. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Economic Discontent: Third parties often emerge when voters feel mainstream parties ignore economic inequalities or crises

- Social Issues: Polarizing topics like abortion, LGBTQ+ rights, or immigration can fuel third-party growth

- Political Alienation: Voters disillusioned with the two-party system seek alternatives for representation

- Electoral Failures: Perceived failures of major parties in addressing key issues drive third-party support

- Charismatic Leaders: Strong, appealing leaders can galvanize support for third-party movements

Economic Discontent: Third parties often emerge when voters feel mainstream parties ignore economic inequalities or crises

Economic discontent has long been a fertile ground for the rise of third parties in American politics. When voters perceive that the two dominant parties—Democrats and Republicans—are failing to address pressing economic inequalities or crises, they often turn to alternative voices that promise radical change or targeted solutions. The Great Depression of the 1930s, for instance, saw the rise of Huey Long’s Share Our Wealth movement, which advocated for wealth redistribution and a guaranteed minimum income. Though Long’s movement didn’t solidify into a lasting third party, it exemplified how economic desperation can fuel support for outsider candidates and platforms.

To understand this dynamic, consider the steps that lead to third-party emergence during economic turmoil. First, identify the specific economic grievances driving voter frustration—whether it’s wage stagnation, income inequality, or corporate bailouts. Second, analyze how mainstream parties respond (or fail to respond) to these issues. For example, during the 2008 financial crisis, many voters felt both parties prioritized Wall Street over Main Street, creating an opening for third-party candidates like Jill Stein and Gary Johnson in 2012 and 2016. Third, examine how third parties capitalize on this discontent by offering clear, differentiated policies, such as Bernie Sanders’s calls for a $15 minimum wage or Andrew Yang’s universal basic income proposal.

However, leveraging economic discontent isn’t without risks. Third parties must tread carefully to avoid being labeled as single-issue or overly radical. For instance, while the Green Party’s focus on economic and environmental justice resonates with some voters, its inability to broaden its appeal has limited its electoral impact. Similarly, the Reform Party, founded by Ross Perot in the 1990s, gained traction by highlighting the national debt and trade deficits but struggled to sustain momentum beyond Perot’s candidacy. The takeaway? Third parties must balance specificity with inclusivity to translate economic discontent into lasting political influence.

A comparative analysis reveals that third parties often thrive when they frame economic issues in ways that resonate with diverse demographics. The Progressive Party of 1912, led by Theodore Roosevelt, appealed to middle-class voters by advocating for trust-busting and labor rights. In contrast, the Populist Party of the late 19th century focused on agrarian economic issues, drawing support from farmers in the South and West. Today, third parties like the Working Families Party align with labor unions and low-wage workers, while the Libertarian Party targets fiscally conservative voters disillusioned with government spending. By tailoring their messages to specific economic pain points, these parties demonstrate how discontent can be channeled into political action.

Finally, practical tips for voters and activists underscore the importance of recognizing when economic discontent warrants third-party support. Start by evaluating whether mainstream parties are genuinely addressing your economic concerns—not just in rhetoric, but in policy action. Engage with third-party platforms critically, assessing their feasibility and alignment with your values. For example, if you’re concerned about income inequality, compare the tax reform proposals of major and minor parties. Remember, voting for a third party isn’t just a protest vote—it’s a strategic decision to reshape the political landscape. By harnessing economic discontent effectively, voters can push mainstream parties to prioritize issues that matter most.

Lyndon B. Johnson's Political Party Affiliation: A Historical Overview

You may want to see also

Social Issues: Polarizing topics like abortion, LGBTQ+ rights, or immigration can fuel third-party growth

In the United States, social issues like abortion, LGBTQ+ rights, and immigration often divide the electorate into starkly opposing camps. These polarizing topics create fertile ground for third parties to emerge, as they can capitalize on the dissatisfaction of voters who feel alienated by the binary choices offered by the Democratic and Republican parties. For instance, the Libertarian Party has long advocated for a more hands-off approach to social issues, attracting voters who feel both major parties are too intrusive in personal matters. Similarly, the Green Party has gained traction by emphasizing environmental and social justice issues that are often sidelined in mainstream political discourse.

Consider the issue of abortion. Following the Supreme Court’s 2022 Dobbs decision, which overturned Roe v. Wade, the political landscape became even more polarized. While Democrats largely advocate for abortion rights and Republicans push for restrictions, third parties like the Progressive Party or smaller single-issue groups have stepped in to offer more nuanced positions. These parties appeal to voters who feel the major parties’ stances are too extreme or fail to address their specific concerns, such as late-term abortion regulations or healthcare access in rural areas. By providing alternative frameworks, these third parties can carve out a niche in an increasingly fractured electorate.

LGBTQ+ rights present another arena where third parties can thrive. While Democrats generally support expansive LGBTQ+ rights and Republicans often oppose them, third parties like the Socialist Party or the Justice Party can offer more radical or intersectional approaches. For example, they might focus on economic policies that specifically benefit LGBTQ+ individuals, such as anti-discrimination laws in housing or employment, or advocate for comprehensive healthcare that includes gender-affirming care. These positions resonate with voters who believe the major parties are either too slow to act or insufficiently committed to meaningful change.

Immigration is yet another polarizing issue that fuels third-party growth. The Democratic and Republican parties often frame immigration debates in starkly opposing terms: open borders versus strict enforcement. Third parties, however, can introduce more nuanced solutions. For instance, the Forward Party has proposed a skills-based immigration system that prioritizes economic needs while ensuring humane treatment of migrants. Such proposals attract voters who are dissatisfied with the major parties’ all-or-nothing approaches and seek pragmatic, compassionate solutions.

To maximize their impact, third parties must strategically leverage these social issues. First, they should identify specific voter demographics alienated by the major parties’ positions. For example, moderate Republicans uncomfortable with their party’s hardline stance on immigration might be receptive to a third party advocating for a balanced approach. Second, third parties should use digital platforms to amplify their message, targeting younger voters who are more likely to support alternative candidates. Finally, they must build coalitions with grassroots organizations focused on these social issues, as this can provide both credibility and organizational support. By doing so, third parties can transform polarizing topics into opportunities for growth and influence.

Understanding the Political Continuum: A Comprehensive Guide to Ideological Spectrums

You may want to see also

Political Alienation: Voters disillusioned with the two-party system seek alternatives for representation

In the United States, the two-party system has long dominated political discourse, leaving many voters feeling unrepresented and disillusioned. This political alienation fuels the rise of third parties as voters seek alternatives that better align with their values and beliefs. The Democratic and Republican parties, while historically significant, often fail to address the nuanced concerns of a diverse electorate, leading to a growing sense of disenfranchisement. For instance, issues like climate change, income inequality, and healthcare reform are frequently sidelined or approached with partisan rigidity, leaving voters craving more innovative and inclusive solutions.

Consider the case of younger voters, aged 18–30, who are increasingly turning to third parties as a means of expressing their dissatisfaction with the status quo. This demographic, often labeled as politically disengaged, is in fact highly engaged but feels alienated by the polarizing rhetoric and gridlock of the two-party system. Third parties, such as the Green Party or the Libertarian Party, offer these voters a platform to advocate for progressive environmental policies or individual liberties, respectively. By supporting these alternatives, young voters are not just casting a ballot—they are making a statement about the kind of political representation they demand.

To effectively address political alienation, voters must first recognize the structural barriers that third parties face, such as restrictive ballot access laws and winner-take-all electoral systems. These obstacles are designed to maintain the dominance of the two major parties, further marginalizing alternative voices. A practical step for alienated voters is to engage in grassroots efforts to reform these systems, such as advocating for ranked-choice voting or lowering ballot access requirements. By doing so, they can help create a more level playing field where third parties have a realistic chance to compete and represent their interests.

Persuasively, it’s clear that political alienation is not merely a symptom of voter apathy but a direct response to the failures of the two-party system. Third parties rise because they offer a pathway for voters to reclaim their political agency and challenge the entrenched power structures that perpetuate alienation. For those feeling unrepresented, supporting third parties is not just a vote—it’s a call for systemic change. By embracing these alternatives, voters can push for a more inclusive and responsive political landscape, one that truly reflects the diversity of American society.

Understanding the Role and Influence of a Political Boss

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.53 $16.99

$13.99 $27.95

Electoral Failures: Perceived failures of major parties in addressing key issues drive third-party support

Voters often turn to third parties when they perceive that major parties are failing to address critical issues effectively. This dissatisfaction can stem from a variety of factors, including policy stagnation, partisan gridlock, or a lack of meaningful action on pressing concerns. For instance, the Green Party’s rise in the 2000s was fueled by frustration over the Democratic Party’s perceived weakness on environmental issues, while the Libertarian Party has gained traction among those disillusioned with both parties’ stances on government spending and individual liberties. These examples illustrate how perceived failures of major parties create openings for third-party alternatives.

Consider the issue of healthcare reform. Despite widespread public support for solutions like universal healthcare, neither major party has fully addressed the issue to the satisfaction of all voters. Democrats have pushed for incremental changes, such as the Affordable Care Act, while Republicans have focused on repealing it without offering a comprehensive alternative. This policy vacuum has allowed third parties like the Progressive Party to advocate for single-payer systems, attracting voters who feel the major parties are out of touch with their needs. To capitalize on this, third parties must clearly articulate their solutions and highlight the major parties’ shortcomings in addressing the issue.

Another example is climate change, where major parties’ responses have often been criticized as insufficient. While Democrats have proposed policies like the Green New Deal, they face internal divisions and Republican opposition, leading to limited progress. Republicans, meanwhile, have largely downplayed the issue or favored industry-friendly approaches. This perceived failure has bolstered support for the Green Party, which offers a more aggressive and focused environmental agenda. Third parties can leverage such issues by framing themselves as the only viable option for voters seeking real change, rather than incremental or partisan solutions.

However, third parties must navigate challenges to effectively capitalize on these failures. One major hurdle is the winner-take-all electoral system, which marginalizes parties outside the two-party duopoly. To overcome this, third parties should focus on local and state-level races, where they can build a track record of success and demonstrate their ability to govern. Additionally, they must avoid internal divisions and present a unified front, as infighting can erode voter trust. Practical steps include coalition-building with like-minded groups, leveraging social media to amplify their message, and focusing on specific, achievable policy goals to establish credibility.

In conclusion, perceived failures of major parties in addressing key issues create fertile ground for third-party support. By identifying these failures and offering clear, compelling alternatives, third parties can attract disillusioned voters. However, success requires strategic focus, unity, and a willingness to start small and build momentum. For voters, supporting third parties can be a way to push major parties to address neglected issues, even if the third party itself does not win. This dynamic underscores the importance of third parties in shaping the political landscape, even when electoral victories remain elusive.

Unveiling Military Personnel's Political Party Affiliations: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Charismatic Leaders: Strong, appealing leaders can galvanize support for third-party movements

Charismatic leaders have the power to transform political landscapes, and their impact on third-party movements in American politics is a testament to this. Consider the case of Ross Perot in the 1992 presidential election. With his folksy demeanor, business acumen, and direct communication style, Perot captured nearly 19% of the popular vote, a remarkable feat for an independent candidate. His ability to connect with voters on issues like the national debt and government inefficiency demonstrated how a single, compelling figure can galvanize support for ideas that fall outside the two-party mainstream. Perot’s success wasn’t just about policy; it was about his persona—a self-made billionaire who spoke truth to power, appealing to voters disillusioned with partisan politics.

To harness the power of charismatic leadership in third-party movements, focus on three key strategies. First, identify leaders with a unique personal narrative that resonates with voters. For instance, a candidate who overcame significant adversity or embodies a specific cultural identity can inspire loyalty. Second, leverage their communication skills to simplify complex issues. Charismatic leaders excel at breaking down policy into relatable terms, as Perot did with his charts and plainspoken explanations. Third, encourage these leaders to build a cult of personality without overshadowing the movement’s core values. The goal is to use their appeal as a vehicle for the party’s message, not as the message itself.

However, relying on charismatic leaders carries risks. Their dominance can make movements vulnerable to collapse if they exit the stage, as seen with Perot’s Reform Party after his departure. To mitigate this, third parties should institutionalize their platforms, ensuring they outlast any single figure. Additionally, charismatic leaders must balance inspiration with substance. Voters drawn in by personality may demand policy depth over time, as evidenced by the eventual fading of Perot’s influence when his solutions lacked detail. Pairing charisma with a robust policy framework is essential for long-term viability.

Comparatively, international examples like France’s Emmanuel Macron and Brazil’s Lula da Silva illustrate how charismatic leadership can reshape political systems. Macron’s En Marche! movement disrupted France’s traditional party structure, while Lula’s personal story and rhetorical skill propelled the Workers’ Party to power. These cases highlight that charisma, when combined with strategic organization, can overcome systemic barriers to third-party success. In the U.S. context, where structural hurdles like winner-take-all elections favor the two-party system, charismatic leaders must work even harder to sustain momentum, often requiring grassroots mobilization and innovative campaign tactics.

In practice, third-party movements should treat charismatic leaders as catalysts, not saviors. Start by identifying potential leaders through local or niche platforms, allowing them to build credibility before scaling nationally. Invest in media training to amplify their appeal without sacrificing authenticity. Finally, create succession plans to ensure the movement’s survival beyond the leader’s tenure. By doing so, third parties can leverage charisma as a tool for growth while avoiding the pitfalls of over-reliance on a single figure. The rise of third parties in American politics often begins with a compelling leader, but its sustainability depends on the structures built around them.

Registering a Political Party in the USA: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Third parties often rise in response to issues or concerns that the two major parties (Democrats and Republicans) fail to address adequately, such as economic inequality, social justice, or environmental policies.

Voter dissatisfaction with the two-party system, polarization, or the lack of representation of specific ideologies fuels support for third parties as alternatives.

The winner-take-all electoral system and high barriers to ballot access make it difficult for third parties to gain traction, but they can still influence national conversations or act as spoilers in close elections.

While third parties rarely win elections, they often push major parties to adopt their ideas or policies, leading to long-term shifts in the political landscape, such as the Progressive Party's influence on early 20th-century reforms.