Political parties often strive to avoid contested conventions because they can lead to internal divisions, prolonged uncertainty, and weakened unity ahead of a general election. A contested convention occurs when no single candidate secures a majority of delegates during the primary season, forcing multiple rounds of voting at the party's national convention. This scenario exposes ideological and personal rifts within the party, as factions vie for influence and control. The prolonged process can drain resources, distract from messaging, and provide opponents with ammunition to exploit vulnerabilities. Additionally, the perception of disarray can alienate voters, undermining the party’s credibility and electoral prospects. To mitigate these risks, parties encourage candidates to consolidate support early, broker deals, or withdraw strategically, ensuring a clear nominee emerges before the convention and preserving party cohesion for the critical campaign ahead.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Unpredictability | Contested conventions are inherently unpredictable, making it difficult for parties to control the outcome and potentially leading to unexpected nominees. |

| Divisiveness | Prolonged contests can expose and exacerbate internal party divisions, damaging party unity and making it harder to rally support for the eventual nominee. |

| Resource Drain | Contested conventions are expensive, diverting resources away from the general election campaign and potentially weakening the party's overall position. |

| Negative Media Attention | Prolonged fights for the nomination attract negative media coverage, highlighting party infighting and potentially alienating voters. |

| Delayed Campaign Start | A contested convention delays the start of the general election campaign, giving the opposing party a head start in fundraising, organizing, and messaging. |

| Weakened Nominee | A nominee emerging from a bitter contested convention may be damaged by the process, making it harder for them to unite the party and appeal to a broader electorate. |

| Voter Fatigue | Prolonged nomination battles can lead to voter fatigue and disengagement, potentially depressing turnout in the general election. |

| Loss of Momentum | A contested convention can stall the party's momentum, allowing the opposing party to gain ground and define the narrative of the election. |

Explore related products

$11.29 $19.99

$24.99

What You'll Learn

- Fear of Party Division: Contested conventions can expose deep fractures within a party, weakening unity

- Unpredictable Outcomes: Lack of a clear nominee increases uncertainty, risking unexpected or unpopular candidates

- Resource Drain: Prolonged nomination battles divert funds and energy from the general election

- Media Scrutiny: Extended contests invite negative press, damaging the party’s public image and credibility

- Voter Fatigue: Drawn-out processes alienate voters, reducing enthusiasm and turnout in the general election

Fear of Party Division: Contested conventions can expose deep fractures within a party, weakening unity

Contested conventions are a political party's worst nightmare, not because of the logistical challenges they pose, but due to the potential for exposing and exacerbating internal divisions. When a party's presidential nomination remains undecided heading into its national convention, the ensuing battle can lay bare ideological, regional, and personal fractures that threaten the party's unity. This vulnerability is a primary reason why parties invest significant effort in avoiding such scenarios.

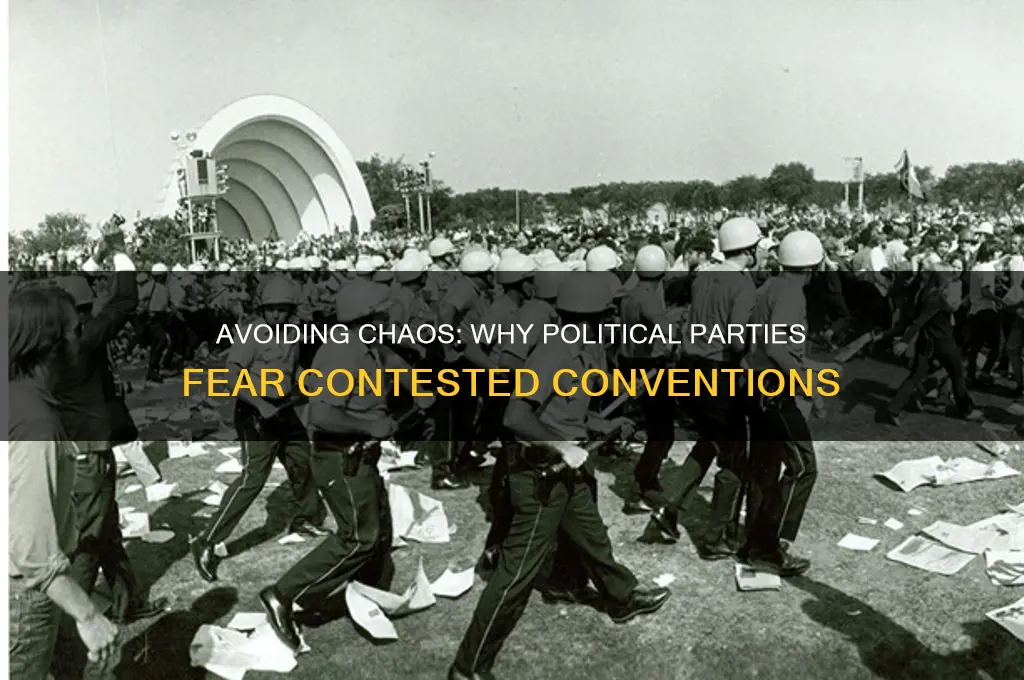

Consider the 1968 Democratic National Convention, a pivotal example of how contested conventions can become a public spectacle of party disunity. As anti-war protesters clashed with police outside the Chicago convention hall, inside, the party was torn between supporters of Vice President Hubert Humphrey and Senator Eugene McCarthy, with George McGovern also in the mix. The convention became a symbol of the Democratic Party's deep divisions over the Vietnam War, racial inequality, and generational conflicts. This internal strife not only weakened the party's ability to present a unified front against Richard Nixon but also left lasting scars that affected the party's cohesion for years.

To avoid such outcomes, parties employ various strategies. First, they encourage candidates to drop out before the convention if they have no mathematical path to victory, thereby preventing a multi-ballot contest. Second, party leaders often engage in behind-the-scenes negotiations to broker a consensus candidate, as seen in the 1924 Democratic National Convention, which took 103 ballots to nominate John W. Davis. However, such prolonged battles are rare today due to the risks involved. Third, parties use superdelegates or automatic delegates—party insiders who can vote at the convention—to influence the outcome and prevent a contested convention. These delegates are often tasked with ensuring party unity by rallying behind a viable candidate.

The fear of division is not just about the immediate aftermath of a contested convention but also about the long-term consequences. A party that appears divided is less appealing to independent voters, who often prioritize stability and coherence. Moreover, internal conflicts can lead to reduced fundraising, as donors hesitate to invest in a party that seems unable to unite behind a single candidate. For instance, the 2016 Republican primary, while not resulting in a contested convention, highlighted the risks of a crowded field and bitter infighting, which initially raised concerns about the party's ability to coalesce around Donald Trump.

In practical terms, parties must focus on early consensus-building and transparent processes to mitigate the risk of division. This includes fostering dialogue among factions, ensuring that primary rules are fair and inclusive, and promoting candidates who can appeal to diverse segments of the party. By addressing these issues proactively, parties can reduce the likelihood of a contested convention and maintain the unity necessary to compete effectively in general elections. The lesson is clear: avoiding contested conventions is not just about procedural efficiency but about preserving the party's core strength—its ability to stand united.

Understanding Turkey's Political Landscape: Key Factors and Dynamics

You may want to see also

Unpredictable Outcomes: Lack of a clear nominee increases uncertainty, risking unexpected or unpopular candidates

Political parties dread contested conventions because they transform a carefully orchestrated coronation into a high-stakes crapshoot. Without a clear frontrunner, the convention floor becomes a battleground where delegates, not voters, wield disproportionate power. This shift from a democratic process to backroom dealing alienates the electorate and undermines the party’s credibility. The 1924 Democratic National Convention, which required 103 ballots to nominate John W. Davis, exemplifies this chaos. The prolonged infighting left the party divided and weakened, contributing to Davis’s landslide defeat. Such historical precedents highlight why parties prioritize unity over uncertainty.

Consider the mechanics of a contested convention: delegates, initially bound to primary winners, become free agents after the first ballot. This freedom invites intense lobbying, horse-trading, and unpredictable alliances. A candidate who entered the convention with modest support could emerge as the nominee through strategic maneuvering, not popular appeal. For instance, the 1952 Democratic Convention saw Adlai Stevenson rise unexpectedly after three ballots, despite not being a primary contender. While Stevenson was a capable candidate, his nomination reflected the convention’s unpredictability rather than a clear mandate from voters. This disconnect between the party elite and the electorate can sow distrust and disillusionment.

The risk of an unpopular nominee further compounds the problem. Contested conventions often elevate candidates who appeal to the party’s base but lack broad appeal. Take the 1968 Democratic Convention, where Hubert Humphrey secured the nomination despite not competing in a single primary. His selection alienated anti-war voters, contributing to the party’s defeat. Similarly, a modern-day scenario could see a polarizing figure emerge, alienating moderates and independents. In an era where elections are won in the center, such an outcome could be catastrophic. Parties, therefore, prioritize clarity to avoid handing their opponents a divisive target.

To mitigate these risks, parties employ strategies like superdelegates and winner-take-all primaries to expedite nominee selection. However, these measures are not foolproof. A close race or late surge by a divisive candidate can still trigger a contested convention. For voters and activists, the takeaway is clear: early and decisive engagement in primaries is crucial. By rallying behind a candidate before the convention, supporters can prevent the uncertainty that breeds unpredictable outcomes. Parties, meanwhile, must balance control with inclusivity to maintain legitimacy without courting chaos. The lesson from history is unmistakable: contested conventions are a gamble few can afford to take.

George Carlin's Political Party: Unraveling the Comedian's Affiliation

You may want to see also

Resource Drain: Prolonged nomination battles divert funds and energy from the general election

Prolonged nomination battles within political parties act as financial black holes, devouring resources that could otherwise fuel a robust general election campaign. Consider the 2016 Republican primary, where a crowded field of 17 candidates stretched the race well into the spring. This extended contest forced campaigns to burn through millions on advertising, travel, and staff salaries, leaving the eventual nominee, Donald Trump, with a depleted war chest just as the general election began. This scenario illustrates a critical vulnerability: every dollar spent on internal party competition is a dollar not spent on attacking the opposing party or mobilizing voters in key battleground states.

The resource drain extends beyond mere finances. A protracted nomination fight demands relentless energy from party leaders, strategists, and grassroots organizers. These individuals, who could be crafting messaging, building coalitions, or registering voters for the general election, are instead consumed by the internecine struggle. This diversion of manpower is particularly damaging in swing states, where local organizers are crucial for door-to-door canvassing and get-out-the-vote efforts. The 2008 Democratic primary, which dragged on for months between Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, serves as a cautionary tale. While the eventual nominee, Obama, ultimately prevailed, the prolonged battle left the party's ground game weakened in several key states, potentially costing them votes in the general election.

To mitigate this resource drain, parties employ various strategies. One approach is to encourage early consolidation around a frontrunner, as seen in the 2020 Democratic primary, where Joe Biden's strong performance in early states quickly marginalized his opponents. Another tactic is to implement rules that discourage prolonged contests, such as awarding delegates on a winner-take-all basis or setting earlier filing deadlines. However, these measures are not foolproof, as they can also stifle competition and alienate voters who feel their voices are being suppressed.

Ultimately, the resource drain caused by prolonged nomination battles is a double-edged sword. While a competitive primary can energize the base and test a candidate's mettle, it can also leave the party financially and organizationally weakened for the general election. Striking the right balance between a robust nomination process and resource conservation is a delicate task, one that requires strategic foresight and a willingness to adapt to the unique dynamics of each election cycle. Parties that fail to navigate this challenge risk entering the general election at a significant disadvantage, their resources depleted and their energy dissipated in the internecine struggle.

How Political Parties Transform Election Methods and Voter Engagement

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Media Scrutiny: Extended contests invite negative press, damaging the party’s public image and credibility

Prolonged political contests act as a magnet for media scrutiny, turning every misstep, disagreement, and strategic blunder into front-page news. Journalists thrive on conflict, and extended battles between candidates provide ample material for negative press. A single offhand remark, a past controversy, or a policy inconsistency can be amplified, overshadowing the party’s core message. For instance, the 2016 Republican primary’s prolonged nature led to relentless coverage of candidate infighting, which weakened the eventual nominee’s standing with independent voters. This dynamic underscores why parties prioritize swift resolutions to avoid becoming fodder for a 24-7 news cycle that thrives on division.

Consider the mechanics of media coverage during extended contests: every debate, every campaign stop, and every endorsement becomes an opportunity for opponents to attack and for journalists to dissect. The cumulative effect is a distorted public image, as minor flaws are magnified while strengths are overlooked. A party’s credibility suffers when its candidates appear more focused on internal battles than on addressing voter concerns. For example, the 1980 Democratic convention’s prolonged struggle between Jimmy Carter and Ted Kennedy resulted in media narratives of a fractured party, which contributed to Carter’s eventual defeat. Such historical lessons highlight the risks of allowing contests to drag on under the unforgiving gaze of the press.

To mitigate media-driven damage, parties employ strategies to shorten contests, such as front-loading primaries or encouraging early endorsements. These tactics aim to create an aura of inevitability around a frontrunner, reducing the incentive for negative coverage. However, even these measures are not foolproof. In 2008, the prolonged Democratic primary between Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton generated months of headlines about racial tensions and party disunity, despite efforts to control the narrative. This example illustrates that once a contest extends beyond a certain point, media scrutiny becomes a self-sustaining force, feeding on every new development.

The takeaway is clear: parties must act decisively to avoid contested conventions, as the media’s role in amplifying negativity is both predictable and relentless. Practical steps include fostering early consensus among party leaders, discouraging divisive rhetoric, and leveraging data-driven strategies to identify a viable candidate quickly. By minimizing the duration of internal contests, parties can preserve their public image and maintain focus on their broader agenda. In an era where media cycles move at lightning speed, the cost of indecision is simply too high.

Nevada's SP 189: Which Political Party Authored the Bill?

You may want to see also

Voter Fatigue: Drawn-out processes alienate voters, reducing enthusiasm and turnout in the general election

Prolonged nomination battles within political parties can exhaust the electorate, diminishing their engagement and participation in the general election. Consider the 2008 Democratic primary, which stretched over 18 months, pitting Barack Obama against Hillary Clinton. By the time Obama secured the nomination, polls showed a segment of Clinton’s supporters expressing reluctance to vote for him in November. This fatigue wasn’t just emotional—it translated into measurable apathy, with turnout among younger and first-time voters, a key Obama demographic, dipping in critical swing states.

To mitigate voter fatigue, parties must streamline their nomination processes. Limiting the number of debates, for instance, can reduce overexposure. In 2016, the Republican Party held 12 primary debates, compared to the Democrats’ 9, and the latter’s more concise schedule correlated with higher sustained interest. Additionally, setting earlier deadlines for states to hold primaries can compress the timeline, ensuring a nominee emerges by late spring. This allows the party to pivot quickly to the general election, refocusing voter energy on the ultimate goal.

A cautionary tale lies in the 1968 Democratic Convention, where a protracted and chaotic nomination process alienated voters, contributing to Hubert Humphrey’s narrow loss to Richard Nixon. Modern campaigns should heed this lesson by prioritizing unity over division. For example, candidates trailing in delegates by a significant margin (e.g., 20% or more) should consider conceding earlier to avoid dragging out the contest. This not only preserves party cohesion but also prevents voter disillusionment, as prolonged infighting often dominates media narratives, overshadowing policy discussions.

Practical steps for campaigns include monitoring voter engagement metrics, such as declining volunteer sign-ups or social media interactions, as early indicators of fatigue. Parties can also invest in data-driven strategies to re-energize disengaged voters, such as targeted messaging campaigns highlighting shared values rather than differences. By treating voter fatigue as a preventable condition, not an inevitable outcome, parties can ensure their base remains mobilized through Election Day.

Travis Kelce's Political Party: Unraveling the NFL Star's Affiliation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A contested convention occurs when no single candidate secures a majority of delegates before a political party's national convention, forcing delegates to decide the nominee through multiple rounds of voting.

Parties avoid contested conventions because they can lead to internal divisions, prolonged uncertainty, and weakened unity, potentially harming the party's chances in the general election.

A contested convention often exposes deep fractures within the party, as factions rally behind different candidates, making it harder to unite behind a single nominee afterward.

Yes, contested conventions can be financially draining due to extended campaigns, legal battles, and the need for additional resources to manage the convention process.

Yes, contested conventions can damage a party's general election prospects by giving the opposing party more time to organize, fundraise, and attack the divided nominee.