The 16th Amendment, which came into effect on February 3, 1913, was a response to the Pollock decision, which stated that Congress could not impose a tax on income derived from real or personal property without apportionment among the states. The amendment grants Congress the authority to issue an income tax without having to determine it based on population. The amendment was ratified by 36 states out of 48, and it shifted the way the federal government received its funding.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date of proposal | July 2, 1909 |

| Date of ratification | February 3, 1913 |

| Ratifying states | 36 out of 48 states |

| Amendment number | 16 |

| Amendment type | Constitutional |

| Amendment name | The Sixteenth Amendment |

| Amendment proposer | President William H. Taft |

| Amendment supporters | Theodore Roosevelt, "Insurgent" Republicans, Progressive Party, Democratic Party |

| Amendment opposers | Conservative senators, Republican Party |

| Amendment rationale | To grant Congress the authority to issue an income tax without having to determine it based on population |

| Amendment impact | Shifted the way the federal government received funding |

Explore related products

$18.23 $25.99

What You'll Learn

The 16th Amendment's impact on the federal government's funding

The 16th Amendment, passed by Congress on July 2, 1909, and ratified on February 3, 1913, established Congress's right to impose a federal income tax. This amendment changed a portion of Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution, which previously required direct taxes to be collected based on the population of the states. The official text of the 16th Amendment states:

> "The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration."

The 16th Amendment had a significant impact on the federal government's funding by shifting the way it received funding for its works. Before the introduction of the income tax, the majority of funds given to the federal government came from tariffs on domestic and international goods. The introduction of the income tax through the 16th Amendment provided a new source of revenue for the federal government, allowing them to collect taxes directly from individuals' incomes.

The amendment also had a social and economic impact, as it shifted the burden of funding the government away from working-class consumers and towards high-earning businessmen. Proponents of the income tax believed that high tariff rates contributed to income inequality and wanted to redistribute the tax burden more fairly. This amendment was particularly supported by citizens in the West and South, who believed it would be an easier way to raise funds from those less well-off. Additionally, the income tax provided a more stable source of revenue for the federal government, as it was less dependent on the fluctuations of trade and tariffs.

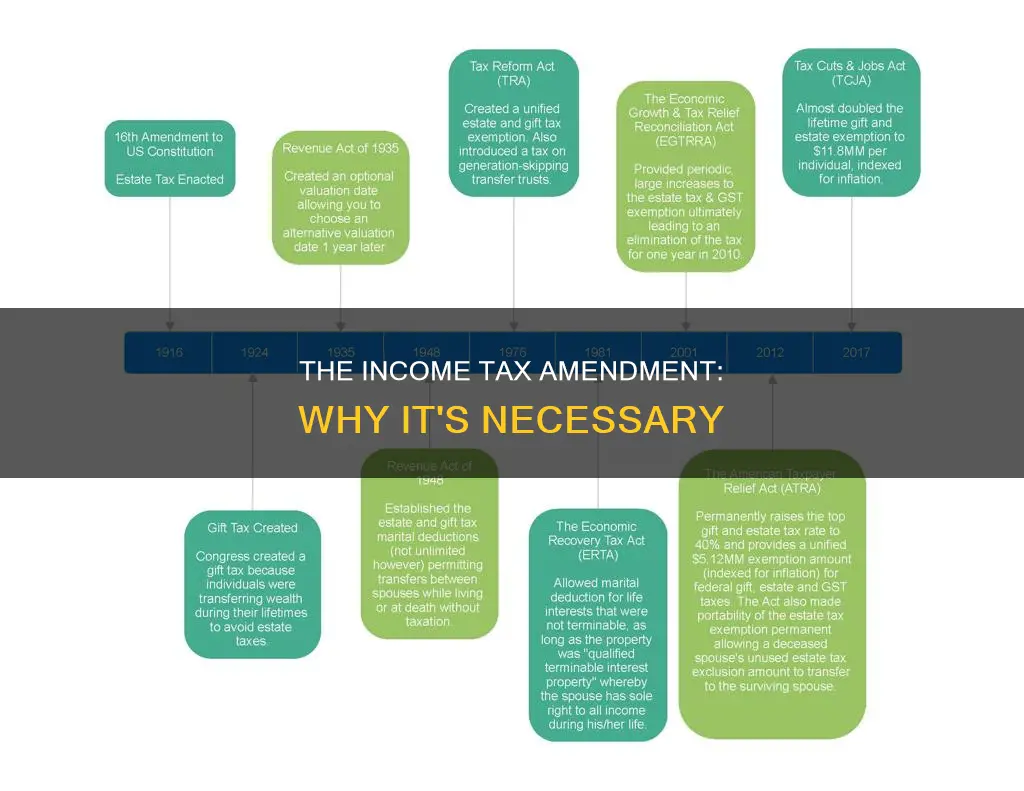

The 16th Amendment also led to the enactment of the Revenue Act of 1913, which further solidified the federal government's authority to collect income taxes. While the initial impact of the income tax in 1913 was limited due to generous exemptions and deductions, over time, the federal government has continued to levy income taxes and expand its revenue stream. The Supreme Court upheld the income tax in the 1916 case of Brushaber v. Union Pacific Railroad Co., ensuring the longevity of the income tax as a source of funding for the federal government.

The Women's Suffrage Amendment: A Constitutional Victory

You may want to see also

Progressive goals and the 1912 election

The 1912 election was a significant event in American history, representing the high-water mark of the Progressive Era in American electoral politics. The election featured three major presidential candidates (and one significant minor candidate), each represented by four separate parties, all of which professed to champion "progressive" politics.

The incumbent, William Howard Taft, ran for reelection as a conservative Republican. However, his former friend and secretary of War, Theodore Roosevelt, also sought the Republican nomination, causing a split in the party. Roosevelt, a progressive, ran on the Progressive ""Bull Moose" Party ticket, championing progressive ideals such as greater government control of the economy, direct democracy, lower tariff rates, income and inheritance taxes, women's suffrage, and the regulation and breaking up of trusts.

Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic governor of New Jersey, was a leading academic in progressive circles and a chief architect of the American progressive movement. In his campaign, Wilson pitched his ""New Freedom" platform as a return to Jeffersonian individualism and states' rights, promising to restore economic competition by busting trusts, lowering tariffs, and reforming the banking system.

The fourth candidate was Eugene V. Debs, running on the Socialist Party ticket. Debs was a perennial presidential candidate for the Socialist Party and received an unprecedented one million popular votes in 1912, marking the height of the Socialist movement in America.

The 1912 election showcased a remarkable debate about the future of American politics, with all four candidates acknowledging the need for fundamental changes to address the challenges posed by industrialization, urbanization, and immigration. The election's impact extended far beyond the immediate results, shaping American reform politics for years to come and influencing the future Democratic administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Amending the Constitution: Who Can Propose Changes?

You may want to see also

The Pollock decision and its consequences

The Pollock decision refers to the landmark case of Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. (157 U.S. 429), which was decided by the United States Supreme Court in 1895. The case centred around the taxation provisions of the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act of 1894, which imposed a 2% tax on incomes over $4000.

In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled in favour of Pollock, stating that the income tax imposed by the Wilson-Gorman Act on income derived from property was an "unapportioned direct tax" and therefore unconstitutional. According to the Constitution at the time, direct taxes had to be imposed in proportion to the population of each state, and the tax in question had not been apportioned accordingly.

The consequences of the Pollock decision were significant. For one, it prevented Congress from implementing another federal income tax, as many Congressmen feared that any new tax would be struck down by the Supreme Court. This situation persisted until 1909, when progressives in Congress attached an income tax provision to a tariff bill. Conservatives, hoping to kill the idea, proposed a constitutional amendment that would enact such a tax, believing it would never be ratified. However, the amendment was ratified by one state legislature after another, and on February 25, 1913, the 16th Amendment took effect, superseding the Pollock decision.

The 16th Amendment granted Congress the authority to impose a federal income tax without having to determine it based on population. This amendment dramatically changed the way the federal government received funding and shifted power away from the states. It also had far-reaching social and economic impacts, as it allowed the government to raise funds more easily from those less well-off, shifting the tax burden away from the middle class and the poor.

Texas Constitution: First Amendment Date

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The amendment's effect on the American way of life

The 16th Amendment, passed by Congress on July 2, 1909, and ratified on February 3, 1913, established Congress's right to impose a federal income tax. The amendment's text reads:

> The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration.

The 16th Amendment's effect on the American way of life was dramatic and far-reaching. Before the amendment, the majority of funds given to the federal government came from tariffs on domestic and international goods. The 16th Amendment changed this by granting Congress the authority to issue an income tax without having to determine it based on population. This shift in the way the federal government received funding had a significant long-term impact.

The amendment also had economic and social impacts. It played a central role in building a powerful American federal government in the 20th century by making it possible to enact a modern, nationwide income tax. Before long, the income tax became the federal government's largest source of revenue. The amendment also addressed concerns about economic power consolidation among the wealthiest Americans.

The 16th Amendment also had political implications. It was part of a wave of federal and state constitutional amendments championed by Progressives in the early 20th century. The amendment's passage was made possible by the rise of the Progressive Party and the victory of the Democratic Party in the 1912 presidential election. The country was generally in a left-leaning mood, with a member of the Socialist Party winning a seat in the U.S. House in 1910.

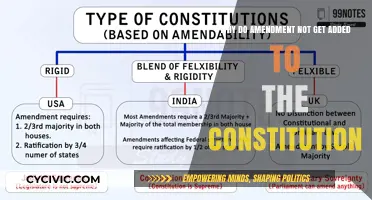

The 16th Amendment also resolved constitutional questions about how to tax income. Before the amendment, there were disputes about whether income taxes constituted direct taxes and how they should be apportioned among the states. The amendment eliminated the requirement that income taxes, as direct taxes, must be apportioned among the states according to population.

The Accused: Constitutional Amendments for Their Rights

You may want to see also

The Supreme Court's interpretation of the amendment

The interpretation of the Sixteenth Amendment by the Supreme Court has evolved over time, with several rulings shaping the legal landscape of income tax in the United States.

Initially, the Supreme Court ruled that income tax was a "direct tax," requiring it to be apportioned among states. This interpretation was outlined in the 1895 case of Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co., where the Court asserted that "direct" taxes included income from rents, dividends, and interest, and thus had to be apportioned based on population. This decision effectively blocked federal income tax.

However, in 1913, the ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment expressly permitted Congress to levy income taxes without apportionment. The amendment's text states, "The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration." This amendment overruled the Pollock decision and clarified the constitutional grounds for income tax, allowing it to become a crucial revenue source for the government.

Despite the amendment, legal scholars continued to debate the interpretation of "direct tax." In Bowers v. Kerbaugh-Empire Co. (1926), the Supreme Court affirmed that the amendment did not bring any new subjects within the taxing power of Congress. Instead, it relieved income taxes from the requirement of apportionment, regardless of whether they were considered direct or indirect taxes. The Court's interpretation in the Brushaber case further supported this, stating that Congress's power to tax income derived from Article I, Section 8, Clause 1 of the original Constitution, not the Sixteenth Amendment.

Over the decades, the Supreme Court continued to hear cases involving income tax law, refining its interpretation of the amendment. For example, Commissioner v. Glenshaw Glass Co. (1955) addressed the definition of "income." The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 also brought fresh scrutiny to income tax law, with opponents arguing that it violated the Sixteenth Amendment by taxing assets rather than income. These ongoing cases demonstrate the dynamic nature of the Supreme Court's interpretation of the income tax amendment.

The Branch That Ratifies Constitutional Amendments

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The 16th Amendment, passed by Congress on July 2, 1909, and ratified on February 3, 1913, established Congress's right to impose a federal income tax without having to determine it based on population.

The 16th Amendment changed the way the federal government received funding for its works. It also shifted power to the federal government, making it more centralized.

Before the 16th Amendment, the majority of funds given to the federal government derived from tariffs on domestic and international goods. Progressives in Congress argued for a federal income tax as it was fairer for the wealthy to pay for the taxes and tariffs that had been paid largely by the middle class and the poor.